In 1923, the white settlers of Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) held a referendum and opted for Home Rule rather than a union with South Africa. The Rhodesian settlers at the time were highly patriotic and loyal to both the King and Empire, many Rhodesian men having recently returned from the carnage of the First World War. Over 6000 white Rhodesian's saw active service on behalf of the Empire during that great conflict, and this figure represented over two thirds of the white male population aged between 15 and 45. Of this figure 732 were killed in action.

Just 20 years later, during the Second World War, some 11,000 European Rhodesians saw active service, including 1,500 women and of these figures, one in ten were either killed in action or died on active service. Rhodesia supplied more troops per head of population than any other country in the British Empire and understandably felt that they had paid for their own country (Rhodesia) in blood and sorrow, on behalf of the Mother Country. However in 1947, India gained her independence and from then on it was simply a question of time as to when each and every British Colony sought self determination. 1953 saw the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and this was to last some ten years and upon its demise it looked very much to the white Rhodesians as if Britain was intent on handing the country directly over to black majority rule, without any safeguards for the white minority.

UDI - Unilateral Declaration of Independence

In October 1965, Rhodesia's white Prime Minister, Ian Smith held talks with Harold Wilson and when these broke down, the white Rhodesian government proclaimed Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence on the 11 November 1965. Almost immediately the Rhodesia war began in between black communist terrorists seeking a black ruled homeland, and the Security Forces of the Rhodesian govenment.

Rhodesia was a 'heart shaped' country located just above South Africa, and it is basically divided into three distinct cultures. The bottom third of the heart was Matabeleland and inhabited by the descendants of the Zulu warriors of Matabele King, Loengula; while the top third of the heart was occupied by the descendants of their traditional enemies; the Mashona. Their third of Rhodesia was know as Mashonaland. In the centre of the heart, between Salisbury and Bulawayo lived the descendants of the original white settlers. All three cultures were actually immigrants to the region, and all three arrived in Rhodesia at about the same period in history, roughly the mid 1800's. The actual inhabitants of Rhodesia being small bands of hunter-gatherer "Bushmen". The Matabele and Mashona had been enemies since the dawn of time, the Matabele nickname for the Mashona being "dirt eaters" from the Matabele practice of standing on the heads of defeated enemies.

The Rhodesian War

From the moment UDI was declared Britain enforced sanctions on the Rhodesian government, and this slowly but surely tightened the noose around the everyday inferstructure of Rhodesian society. The only real friend Rhodesia possessed during the war was South Africa, who continued to trade and assist with exports and also war materials. The terrorists on the other hand, were split into two main factions and these were based on the tribal loyalties of old. The Matabele were under the leadership of Joshua Nkomo, and they sought weapons, training and assistance from Cuba, East Germany and Russia; while the Mashona who were led by Robert Mugabe and were trained in North Korea and China. Throughout the war, Rhodesian farmers grew enough corn, tobacco and cattle to not only feed their own population, but to also export it to their near and starving neighbours in Botswana, Zambia and Mosambique; and who, in return gave succor and comfort to the guerillas.

The war dragged on for some 14 years from 1965 until 1979, being largely overshadowed by the television driven Vietnam conflict. The Rhodesian war was virtually ignored, until the guerillas committed atrocities on various Missionary stations. The war was both bloody and brutal and brought out the very worst in the opposing combatants on all three sides:

RSF (Rhodesian Security Forces - Smith's Army) ZIPRA (Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army - Nkomo's Army) ZANLA (Zimbabwe National Liberation Army - Mugabe's Army)

Lancaster House Talks

During the war there had been many attempts by Smith, Nkomo, Mugabe and Britain to broker an honourable peace deal guaranteeing the rights of the white Rhodesian minority. These meetings were often held aboard war ships and sometimes even trains parked in the middle of high bridges, but all were to no avail until the Lancaster House talks in mid-1979. In April 1979 an election was held in Rhodesia in which 63 percent of the black population voted, and on the 1 June 1979, Bishop Able Muzorewa was sworn in as the first black Prime Minister of Rhodesia. Meanwhile at Lancaster House the Peace talks continued in a rather 'on again - off again' fashion. This state of affairs continued until October and then as the light began to appear at the end of the tunnel, Britain sent out feelers to various Commonwealth nations that troops might be needed for a special operation.

In New Zealand, selection and training began immediately and a force of 75 officers and men were selected and moved to Papakura Camp for specialist training. Other countries did similar training. None of the soldiers were formally told where they might be headed but initially the 75 strong contingent was called 'R Force', similar to 'K Force' (Korea), and 'V Force' (Vietnam). They were also instructed to listen to BBC world news at 0700 each morning so the possibility of a Tour of Duty to Rhodesia was an open secret. Originally, both Mugabe and Nkomo did not want any New Zealanders in the Peacekeeping Force as they were thought to be American puppets. However, when it was pointed out that one man in every four in the New Zealand contingent was 'coloured' (Maori), the New Zealander's became very acceptable.

Operation Agila

On the 5 November 1979, the British Ministry of Defence named Major General John Acland (later Sir John), as the Commander Monitoring Force (CMF). The Headquarters of the Monitoring Force (MF) was based on HQ 8 Field Force from tidworth with the GOG South West District (General Acland), holding the following three appointments:

Commander of the Monitoring Force (CMF) Military Advisor to the Governor of Rhodesia Chairman of the Ceasefire Commission.

Brigadier John Learmont was appointed as Deputy Commander (DCMF), and Brigadier Adam Gurdon was appointed Chief of Staff. The Operation was named "Operation Agila", and the Monitoring Force operational patch was a red, white and blue diamond with a golden sunburst in the centre and a Pangolan (small anteater), with claws extended centred in the sun. This was to be worn on a white brassard. It was also decided that the uniform that was to be worn by all members of the MF was to be 'Jungle Green' fatigues, and that berets would only be worn in camp and 'Jungle Hats' would be worn by all members of the MF serving in the operational areas. This would serve to distinguish them from the Rhodesian Army who wore a very distinctive pattern of camouflage.

Rhodesian Reconnaissance

Due to the war, there was virtually no 'good', up to date information or maps available on Rhodesia, and much of the intitial planning was a series of lectures by ex school teachers and missionaries who had served "out there", and usually before the war. On the 22 November 1979, the British Chief of Staff, Chief Signals Officer, Air Advisor and several other key personel flew to Rhodesia and carried out a detailed recce of Rhodesia, including the thoughts and feelings of both the white's and the black's in regards to how a Commonwealth Force would be received should one arrive in-country. This recce group travelled the length and breadth of Rhodesia and gathered much vital information on how the war was being conducted by all three sides and where the various bases and camps were located. One concern that was taken note of the the liberal use by the guerillas of land mines, it was recommended at this early stage that all Landrovers used by the Monitoring Force would need to be mine proofed and most of this work was done by REME personel at Colchester.

On 8 December 1979, a nine man British advance party was deployed to Rhodesia and began establishing a logistics base in preparation for the Commonwealth Monitoring Force main body, which would include some 1,500 Peacekeepers, including 150 Australians, 22 Fijians, 50 Kenyans, and 75 New Zealanders. As well, Britain provided 800 soldiers, some 300 Royal Air Force personel and a small number of Royal Navy and Royal Marines. The Royal Navy contribution being mainly Doctors.

Main Body Arrival

On the 12 December 1979, Major General Acland and Brigadier Learmont arrived in Salisbury with a small staff and began meeting Rhodesians at all levels at the Operational Headquarters of the RSF. This provided the much needed information on the size and strength of the various teams of Peacekeepers that would be inserted into the various operational areas throughout Rhodesia. The Rhodesians were very much of the opinion that it would become a bloodbath and the cost in Peacekeepers lives would be high. An air of grave concern and tension hung over all aspects of the initial phases of in-country planning and preparation. As well the man destined to be the last British Governor of Rhodesia, Lord Christopher Soames travelled to Salisbury, later describing his dangerous venture as "a leap in the dark".

Meanwhile at Lancaster House the talks continued to drag on through December, and this delay was actually advantageous to General Acland and his staff providing them with valuable time to select the various "Assembly Areas" and "R/V's" that would soon dot the country. It also allowed HQ UKLF time for the packing of stores and equiptment and the marking of vehicles and aircraft to be used during Operation Agila.

On the 20th December 1979, the New Zealand contingent which was the most distant from Rhodesia flew out from RNZAF Base Whenuapai and over the next several days the various nations began to arrive at Salisbury Airport (between the 22nd and 24th of December). Upon arrival each plane load of troops was processed through a reception tent, given an initial briefing and issued with anti-malaria tablets (Maloprim) which were known locally as the "Tuesday Pill". The entire nation was reminded on both radio and television to take their pill each Tuesday. Troops were also given the opportunity to exchange money and were given the location of their billets. The Rhodesian Army built a tented transit camp which accommodated the majority of the troops with the exception of the Fijians, Kenyans and New Zealanders who were accommodated at Morgan High School. Morgan High School was to become the main Headquarters of the Monitoring Force. During this phase of the operation which covered a five day period, more than 60 aircraft sorties landed at Salisbury Airport off-loading more than 1,500 men and a veritable mountain of stores and equipment.

Preparation and Planning

The next several days were packed with detailed briefings, O Groups, and the issuing of stores, ammunition and equipment. As well, due to the height of Rhodesia above sea level, every soldier was required to attend a range shoot and re-zero his personal weapon. The altitude most definitely did make a difference to sight settings. Amongst all ranks of the Monitoring Force from the Commander down there was a very real air of trepidation in regards to the daunting task that lay ahead. At this time the CMF, General Acland went out of his way to personally meet and make himself known to every single member of the Monitoring Force during his initial briefing which was usually held at the RLI Barracks at Cranborne. The briefings included:

The CMF's lecture on the responsibility of of the Monitoring Force. An overview on the background of the war and the politics involved. The background to the operational situation. The CMF's concept of how the operation was to be conducted. The allocation of troops to task. The in-theatre deployment plan. The Rules of Engagement. Communications, this included a crash course on CLANSMAN. The Logistic Plan. A medical briefing, including health and hygiene. An in-country wild-life briefing.

The Ceasefire Monitoring Force "ORBAT"

The Ceasefire Monitoring Force was made up of about 1,500 soldiers from Australia, Britain, Fiji, Kenya and New Zealand, and command and control was maintained at three in-country Headquarters:

The Main HQ was located at Morgan High School. A small HQ and staff located at Government House. An Airhead HQ located at New Sarum Airfield.

Main HQ: was responsible for all detailed planning, preparation, forward deployment, redeployment, day to day running of the operation. Located at the Main HQ was DCMF, all National Contingent Commanders, the operations room, air tasking cell, communications centre, and the A and Q staff.

Government House HQ: The CMF, Chief of Staff and four Staff Officers operated out of Government House and were responsible for liaison with HQ Combined Operations (Rhodesian Security Forces), the HQ Patriotic Front (communists), the conduct of the Ceasefire Commission, and briefing the Governor on military matters.

The Airhead HQ: was responsible for all air tasking matters to and from all Monitoring Force teams in the operational areas.

The Operational Areas during the Rhodesian War were:

A. Operation Ranger - North West Border.

B. Operation Thrasher - Eastern Border.

C. Operation Hurricane - North East Border.

D. Operation Repulse - South East Border.

E. Operation Grapple - Midlands.

F. Operation Splinter - Kariba.

G. Operation Tangent - Matabeleland.

H. "SALOPS" - Salisbury & District.

B. Operation Thrasher - Eastern Border.

C. Operation Hurricane - North East Border.

D. Operation Repulse - South East Border.

E. Operation Grapple - Midlands.

F. Operation Splinter - Kariba.

G. Operation Tangent - Matabeleland.

H. "SALOPS" - Salisbury & District.

The Peacekeeping Forces on the ground, were broken down as follows:

Patriotic Front (communist) Teams -

Operational Area MF HQ = 1 x Lieutenant Colonel and 10 men.

Assembly Places* = 1 x Major/Captain and 16 men. (+ 1 x GPMG).

Rendevous Teams** = 1 x Captain/Lieutenant and 9 men. (+ 1 x GPMG).

* There were 16 Assembly Places (AP November and AP Quebec later closed).

** There were 39 RV's during the Ceasefire period.

Assembly Places* = 1 x Major/Captain and 16 men. (+ 1 x GPMG).

Rendevous Teams** = 1 x Captain/Lieutenant and 9 men. (+ 1 x GPMG).

* There were 16 Assembly Places (AP November and AP Quebec later closed).

** There were 39 RV's during the Ceasefire period.

Rhodesian Security Force Monitoring Teams -

Joint Operation Command (JOC) HQ = 1 x Lieutenant Colonel and 10 men.

Sub JOC Teams (Battalion HQ's) = 1 x Captain/Lieutenant and 4 men.

Company Based Teams = 1 x Lieutenant/Warrant Officer and 1 man.

Border Liaison Teams = 1 Major and 4 men.

Sub JOC Teams (Battalion HQ's) = 1 x Captain/Lieutenant and 4 men.

Company Based Teams = 1 x Lieutenant/Warrant Officer and 1 man.

Border Liaison Teams = 1 Major and 4 men.

Forward Deployment

The decision to deploy the Monitoring Force was made on the 24 December 1979, and the forward deployment took place over the next three days with the Ceasefire coming into effect at 2359 + 1, on the 28th of December. This was an extrememly tense time as no one knew how the communist guerillas in the operational areas might act. Perhaps fortunately for the Monitoring Force, the world at large was starved for News coverage and a great many reporters were in Rhodesia. They were spread widely throughout the country, and their efforts tended to keep everyone honest. During the forward deploment phase the weather was atrocious and RAF aircrew flew missions that would never have been authorised under normal circumstances. There were a number of contacts during this phase of the operation, including: A Rhodesian Escort AFV (Crocodile) was destroyed by a mine near Bulawayo, an RAF Puma helicopter crashed killing the 3 man aircrew, a Hercules aircraft was shot up by small arms fire near Umtali, and an RV Team was ambushed in the Zambezi Valley but escaped without casualities.

The Assembly Phase

The Assembly Phase was a seven day period when all of the communist units and cells spread throughout Rhodesia, and in several of the neighbouring countries were guaranteed unhindered movement into RV's and Assembly Places. Once in the Assembly Place, all communists, both Regular Force and Guerillas were required to register their name, weapon and that weapon's serial number. Both the ZIPRA and ZANLA had played down the size of their forces and over that seven day period more than 22,000 communist soldiers marched into the 16 Assembly Places. The sheer size of the various ZIPRA and ZANLA units created something of a logistics nightmare and to avoid 'under issues', if any communist unit required some special item (eg sanitary pads, female underwear), then a drop was immediately arranged to all of the Assembly Places, sometimes causing much hilarity to the troops on the ground. (ZANLA had quite a sizeable force of female guerillas). The communits were to arrive at the Assembly Places carrying all of their own equipment, however for the most part, most of them carried little more than an AK47, a couple of magazines and the clothes they stood in. Many wore no boots. Food and meat shortages caused major problems on a number of occassions and almost resulted in the deaths of a number of Peacekeepers who were taken hostage. It had been understood that the communists lived on "Sudza" (corn mealie meal), and initially no meat was provided for them. This was quickly rectified, by the CMF importing several planeloads of South African beef.

Once in the Assembly Places, the communists troops became very lax and always carried their personal weapon "locked, cocked and ready to rock"; that is several magazines taped together on the weapon, the weapon cocked with a round in the tube, safety catch 'off', and sights set to maximum range. This resulted in a plague of UD's (unauthorised discharges) and numerous casualties. It also caused tremendous stress and tension amongst the MF Teams. There were even UD's with hand grenades and RPG's resulting in injury and loss of life. As well, there was the ever present danger of mines which continued to take a toll during the entire operation.

Redeployment of RV Teams

The Ceasefire ended on the 4th January 1980 at 2359 + 1, and as most of the communists were now gathered at the various Assembly Places, the RV Teams were disbanded and those men were then added to various Assembly Places so as to boost the numbers there. Assembly Place 'November' and Assembly Place 'Quebec' were both closed as no communists had been recently operating in that area (Northern border), and the Commonwealth troops at those locs were redistributed to some of the larger Assembly Places that were holding several thousand communists. Assembly Place Foxtrot held over 6,000 communists.

The Election Period

This part of the operation lasted from the 5th January 1980, when the Ceasefire ended until the 3 March 1980, which was in fact after the elections had been held, but before the results were announced. The election results were announced on the 4 March 1980. During this period, a contingent of British 'Bobbies' were flown into Rhodesia and they served as observers at the many polling places scattered throughout the country. There were many breaches in the Ceasefire as all three sides attempted to gain a position of strength, as well many guerillas drifted in and out of the Assembly Places, virtually at will and continued their usual programmes of intimidation, rape, robbery and murder.

The elections were said to be about giving the black population a free and fair vote, however, many, many black Rhodesians wanted to vote for Ian Smith but were barred from such a vote under the terms of the Lancaster agreement. This left a two horse race, and as Mugabe and Nkomo jostled for power, it became commonplace for hand grenades to be thrown into the interior of each other's beer halls by supporters.

The Withdrawal

On the 2nd March 1980, all Monitoring Force personel were pulled back to a tented camp in and around New Sarum airport, and immediately the RAF began flying sorties of men and equipment back to the UK and various other Commonwealth countries. Many Rhodesians, and most especially the white population, had been hoping that Joshua Nkomo would win the election, as he was considered the more stable of the two candidates. It came as a shock for most whites when Robert Mugabe was announced as the winner, swiftly changing the name of the country to "Zimbabwe". The whites began leaving in droves. Those who remained were mainly farmers, as they stood to loose everything, as the first law Mugabe passed was that anyone leaving Zimbabwe, could take no more than a couple of hundred dollars with them. Those Rhodesian's who left the country were virtually penniless.

By the 16 March 1980, all of the Monitoring Force had departed from Zimbabwe, apart from a small volunteer group (about 40 men) of British Infantry Instructors who were to train the new Zimbabwe Army. Three weeks later on the 18 April 1980, at a ceremony that was attended by HRH Prince Charles, the Union Jack was lowered for the last time from Government House in Salisbury, and the new African nation of Zimbabwe declared itself a Free and Independent country.

The sun had finally set on the British Empire.

Post Script

Almost as soon as the Monitoring Force left the country, Mugabe and his henchmen set about settling a few of the old scores; not with the whites at that stage, but with his old 'comrade' Joshua Nkomo. Incidents and murders rapidly escalated over the next month and then a short civil war broke out between ZANLA and ZIPRA. As Mugabe was the lawful elected leader of Zimbabwe, he ordered all Units of the old Rhodesian Security Forces into the field and over a period of three days the old RSF units, supported by Gunships fought open battles with Nkomo's ZIPRA Army. As soon as Nkomo's men melted back into the veld, Mugabe requested military assistance from North Korea (he had been supported by Korea and China during the war). Shortly afterward the North Korean 5th Brigade arrived in Zimbabwe and over the period of the next three years committed genocide throughout the Tribal Trustlands of Matabeleland.

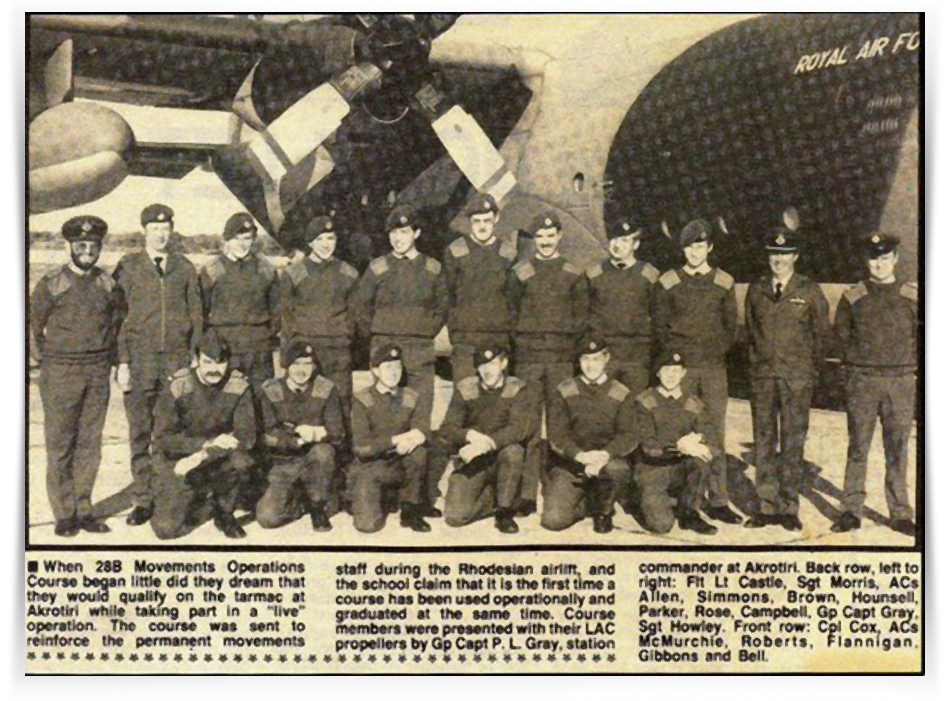

Report by Squadron Leader J H Macdonald

OC UKMAMS Det, latterly S Mov O Rhodesia

OC UKMAMS Det, latterly S Mov O Rhodesia

Operation Agila - From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe

OUTLINE

1. The air movements aspects of Operation Agila can be divided into 5 phases. Firstly, the strategic deployment of the force from UK, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Kenya to Salisbury. Secondly, the tactical move of elements of the Monitoring Force (MF) from Salisbury to dispersal locations within Rhodesia. Thirdly, the resupply phase, both into and within the Theatre. Fourthly, the tactical recovery of dispersed Monitoring Teams to Salisbury. Finally, the strategic recovery from Rhodesia to home countries.

1. The air movements aspects of Operation Agila can be divided into 5 phases. Firstly, the strategic deployment of the force from UK, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Kenya to Salisbury. Secondly, the tactical move of elements of the Monitoring Force (MF) from Salisbury to dispersal locations within Rhodesia. Thirdly, the resupply phase, both into and within the Theatre. Fourthly, the tactical recovery of dispersed Monitoring Teams to Salisbury. Finally, the strategic recovery from Rhodesia to home countries.

THE STRATEGIC DEPLOYMENT

2. The strategic deployment of the MF began on 19th Dec 79 with the departure of VC10 Flt 2285 from Brize Norton en route for Salisbury. This aircraft deployed the 38 Gp route activation party, including 3 UKMAMS teams for Salisbury. On arrival these were divided into 2 teams, each of a Flt Lt and 7 men with a HQ element of a Sqn Ldr (OC UKMAMS Det) and a FS (Cormack). The HQ element was stationed in a Combined Air Transport Operations Centre in Salisbury Civil Airport, together with 38 Gp Ops staffs and USAFE Ops and ALCE staffs. The traffic teams worked on a 12 hr on, 12 hr off shift pattern from a lockup store adjacent to the aircraft hard standing. They were assisted in handling USAF aircraft by 6 USAF Aerial Port personnel.

3. Deplaning passengers were processed through a large marquee erected on open ground adjacent to the aircraft hard standing and were dispersed in contractors’ transport. Cargo also was dispersed by civilian contractors’ vehicles ordered to meet specific chalks. The workload during the 6 days of the airlift was intensive but in general the flow of aircraft was well regulated. However, on occasions, the late arrival of some USAF aircraft created flow conflictions and consequent peaks in workload. Nevertheless, despite working conditions which varied from temperatures of 120 deg Fahrenheit to violent thunderstorms, planned aircraft turn-rounds were in general achieved or reduced.

4. The airlift was completed on 26th Dec with the departure of USAF MAC Flt 5523. By then 1398 passengers and 1,926,552 lbs of cargo had been received from 73 aircraft of 5 nations.

2. The strategic deployment of the MF began on 19th Dec 79 with the departure of VC10 Flt 2285 from Brize Norton en route for Salisbury. This aircraft deployed the 38 Gp route activation party, including 3 UKMAMS teams for Salisbury. On arrival these were divided into 2 teams, each of a Flt Lt and 7 men with a HQ element of a Sqn Ldr (OC UKMAMS Det) and a FS (Cormack). The HQ element was stationed in a Combined Air Transport Operations Centre in Salisbury Civil Airport, together with 38 Gp Ops staffs and USAFE Ops and ALCE staffs. The traffic teams worked on a 12 hr on, 12 hr off shift pattern from a lockup store adjacent to the aircraft hard standing. They were assisted in handling USAF aircraft by 6 USAF Aerial Port personnel.

3. Deplaning passengers were processed through a large marquee erected on open ground adjacent to the aircraft hard standing and were dispersed in contractors’ transport. Cargo also was dispersed by civilian contractors’ vehicles ordered to meet specific chalks. The workload during the 6 days of the airlift was intensive but in general the flow of aircraft was well regulated. However, on occasions, the late arrival of some USAF aircraft created flow conflictions and consequent peaks in workload. Nevertheless, despite working conditions which varied from temperatures of 120 deg Fahrenheit to violent thunderstorms, planned aircraft turn-rounds were in general achieved or reduced.

4. The airlift was completed on 26th Dec with the departure of USAF MAC Flt 5523. By then 1398 passengers and 1,926,552 lbs of cargo had been received from 73 aircraft of 5 nations.

TACTICAL REDEPLOYMENT

5. The dispersal by air of elements of the MF within Rhodesia was planned for 27 and 28 Dec 79. However, because of factors unforeseen in the planning stage 9 additional Hercules sorties were required in the period 24-26Dec. These were all loaded at Salisbury and unloaded at their destination by the duty traffic team concurrently with their strategic commitment. This concurrency was not allowed for in the manpower planning and, in consequence, a very strenuous workload was placed on the traffic teams during this period. Nevertheless, all these sorties with the exception of one, which was postponed due to the late arrival of the Kenyan contingent, were flown as planned.

6. During the 2 days of the planned tactical airlift 26 Hercules sorties were mounted. One traffic team loaded the aircraft at Salisbury; the other, reinforced at times by the HQ element flew with the aircraft to offload at destinations. All these sorties departed and recovered on time. This was a vital factor in the positioning of Rendezvous and Monitoring Teams at their locations by the deadline of 2359 hrs 28 Dec.

5. The dispersal by air of elements of the MF within Rhodesia was planned for 27 and 28 Dec 79. However, because of factors unforeseen in the planning stage 9 additional Hercules sorties were required in the period 24-26Dec. These were all loaded at Salisbury and unloaded at their destination by the duty traffic team concurrently with their strategic commitment. This concurrency was not allowed for in the manpower planning and, in consequence, a very strenuous workload was placed on the traffic teams during this period. Nevertheless, all these sorties with the exception of one, which was postponed due to the late arrival of the Kenyan contingent, were flown as planned.

6. During the 2 days of the planned tactical airlift 26 Hercules sorties were mounted. One traffic team loaded the aircraft at Salisbury; the other, reinforced at times by the HQ element flew with the aircraft to offload at destinations. All these sorties departed and recovered on time. This was a vital factor in the positioning of Rendezvous and Monitoring Teams at their locations by the deadline of 2359 hrs 28 Dec.

RESUPPLY PHASE

7. At the beginning of the Resupply Phase OC UKMAMS Det was re-designated the RAF Staff Movements Officer (RAF S MOV O) Rhodesia and together with the Army Force Movements and Transport Officer (FMTO) formed the Ceasefire Liaison and Monitoring Organizations (CLAMOR) Joint Movements Staff.

8. A Joint Services Air Booking Centre (JABC Rhodesia) was formed at the airport under the day to day control of the RAF S Mov O. The staff of JABC were drawn jointly from UKMAMS and ATLO personnel and throughout the resupply and recovery phases they provided a joint air booking, load control and ATLO function for both strategic and tactical air transport operations.

9. Physical loading and unloading operations remained the direct responsibility of S Mov O and were handled by 2 full MAMS teams working a 24 hours on, 24 hours off shift system. However, at times of peak activity, double shift operations were necessary and on occasions JABC staff were required to further reinforce the traffic teams.

7. At the beginning of the Resupply Phase OC UKMAMS Det was re-designated the RAF Staff Movements Officer (RAF S MOV O) Rhodesia and together with the Army Force Movements and Transport Officer (FMTO) formed the Ceasefire Liaison and Monitoring Organizations (CLAMOR) Joint Movements Staff.

8. A Joint Services Air Booking Centre (JABC Rhodesia) was formed at the airport under the day to day control of the RAF S Mov O. The staff of JABC were drawn jointly from UKMAMS and ATLO personnel and throughout the resupply and recovery phases they provided a joint air booking, load control and ATLO function for both strategic and tactical air transport operations.

9. Physical loading and unloading operations remained the direct responsibility of S Mov O and were handled by 2 full MAMS teams working a 24 hours on, 24 hours off shift system. However, at times of peak activity, double shift operations were necessary and on occasions JABC staff were required to further reinforce the traffic teams.

TACTICAL RESUPPLY

10. In the early stages of the resupply phase, in-theatre Hercules aircraft were tasked to meet specific daily airlift requirements. Often these were not known until late the previous day and the flying programme was seldom finalised before late evening for departures at first light the following day. This led to long frustrating working hours for all the agencies involved; moreover, although a degree of load consolidation was achieved, aircraft were seldom fully utilized and on occasions tasks were duplicated.

11. Clearly this was an unsatisfactory arrangement, and, following discussions between the Hercules Detachment Commander, S Mov O and CLAMOR AQ Staffs 2 internal schedules were designed to meet the emerging pattern of demand for airlift. These provided all the Assembly Places adjacent to airstrips with a Hercules schedule on alternate days. Immediately, the pressure for special airlift reduced significantly and within a few days it became minimal.

12. From the outset the internal schedules operated in the PCF, 44 seat role and offered a round trip payload of 20,000 lbs operating at Military Operating Standard (MOS). This proved to be an ideal combination of role fit and payload offer and remained unchanged throughout the resupply operation.

13. Bookings for all legs of these flights were controlled by JABC and, once this became known to all the agencies involved, it proved to be a workable and effective system of payload control. Physical loading and offloading was handled by 2 MAMS personnel and the aircraft’s Loadmaster working as a team.

14. A number of out-of-theatre tasks were mounted by the in-theatre aircraft in support of the resupply operation. Notably, in late Jan 80 it became necessary to airlift 90 tons of beef from South Africa to supplement Assembly Place rations. These were delivered by 6 Hercules sorties, each averaging 34,000 lbs of payload from Johannesburg to Salisbury, Fort Victoria and Bulawayo. Loading and offloading operations at all these locations were handled by Salisbury-based MAMS teams.

10. In the early stages of the resupply phase, in-theatre Hercules aircraft were tasked to meet specific daily airlift requirements. Often these were not known until late the previous day and the flying programme was seldom finalised before late evening for departures at first light the following day. This led to long frustrating working hours for all the agencies involved; moreover, although a degree of load consolidation was achieved, aircraft were seldom fully utilized and on occasions tasks were duplicated.

11. Clearly this was an unsatisfactory arrangement, and, following discussions between the Hercules Detachment Commander, S Mov O and CLAMOR AQ Staffs 2 internal schedules were designed to meet the emerging pattern of demand for airlift. These provided all the Assembly Places adjacent to airstrips with a Hercules schedule on alternate days. Immediately, the pressure for special airlift reduced significantly and within a few days it became minimal.

12. From the outset the internal schedules operated in the PCF, 44 seat role and offered a round trip payload of 20,000 lbs operating at Military Operating Standard (MOS). This proved to be an ideal combination of role fit and payload offer and remained unchanged throughout the resupply operation.

13. Bookings for all legs of these flights were controlled by JABC and, once this became known to all the agencies involved, it proved to be a workable and effective system of payload control. Physical loading and offloading was handled by 2 MAMS personnel and the aircraft’s Loadmaster working as a team.

14. A number of out-of-theatre tasks were mounted by the in-theatre aircraft in support of the resupply operation. Notably, in late Jan 80 it became necessary to airlift 90 tons of beef from South Africa to supplement Assembly Place rations. These were delivered by 6 Hercules sorties, each averaging 34,000 lbs of payload from Johannesburg to Salisbury, Fort Victoria and Bulawayo. Loading and offloading operations at all these locations were handled by Salisbury-based MAMS teams.

STRATEGIC RESUPPLY

15. Initially the resupply of the MF from UK was effected by a weekly PCF VC10 schedule which routed inbound and outbound via Nairobi. This was later amended to stage through Akrotiri in both directions to provide an enhanced payload offer inbound. Furthermore, the levels of cargo arisings in both directions led to the institution of a weekly Hercules sortie to supplement the VC10. On occasions these were further supplemented by special flights. One of these, a Hercules delivering a replacement Puma aircraft became unserviceable at Nairobi. A Salisbuury-based MAMS team was therefore despatched to Nairobi to effect a load change to a serviceable aircraft. This was achieved in the remarkably short time of 4 hours.

15. Initially the resupply of the MF from UK was effected by a weekly PCF VC10 schedule which routed inbound and outbound via Nairobi. This was later amended to stage through Akrotiri in both directions to provide an enhanced payload offer inbound. Furthermore, the levels of cargo arisings in both directions led to the institution of a weekly Hercules sortie to supplement the VC10. On occasions these were further supplemented by special flights. One of these, a Hercules delivering a replacement Puma aircraft became unserviceable at Nairobi. A Salisbuury-based MAMS team was therefore despatched to Nairobi to effect a load change to a serviceable aircraft. This was achieved in the remarkably short time of 4 hours.

IN-THEATRE RECOVERY

16. With the general improvement in the security situation during the ceasefire period, much of the dispersed equipment and many of the personnel were able to recover from Assembly Places by road. Therefore, the part played by air transportation during the in-theatre recovery was less than that in the deployment. Nevertheless, a substantial amount of equipment was recovered by air during the 14 days leading up to D Day and on D Day itself 12 Hercules sorties were flown. Each sortie recovered 2 mine-plated landrovers and trailers and up to 18 fully kitted troops. 2 MAMS personnel travelled with each aircraft to expedite turn rounds both at forward airstrips and on return to Salisbury.

17. By the end of this phase and including the figures for tactical and strategic resupply, Salisbury based MAMS teams had handled 5815 passengers and 2,591,483 lbs of cargo.

16. With the general improvement in the security situation during the ceasefire period, much of the dispersed equipment and many of the personnel were able to recover from Assembly Places by road. Therefore, the part played by air transportation during the in-theatre recovery was less than that in the deployment. Nevertheless, a substantial amount of equipment was recovered by air during the 14 days leading up to D Day and on D Day itself 12 Hercules sorties were flown. Each sortie recovered 2 mine-plated landrovers and trailers and up to 18 fully kitted troops. 2 MAMS personnel travelled with each aircraft to expedite turn rounds both at forward airstrips and on return to Salisbury.

17. By the end of this phase and including the figures for tactical and strategic resupply, Salisbury based MAMS teams had handled 5815 passengers and 2,591,483 lbs of cargo.

STRATEGIC RECOVERY

18. The strategic recovery plan called for the recovery of non-essential vehicles by sea and the recovery of all personnel, helicopters, specialist vehicles and essential equipment by air. An element of the FCO and the Election Commission were also to be recovered by air.

19. The strategic airlift was closely tailored to meet the MP’s requirement to recover the majority of its personnel to UK on the same day they were to be recovered from Assembly Areas. Accordingly, 5 VC10s in the full passenger role were planned for the first 48 hours of the operation. These were routed inbound via Akrotiri which gave the desired short transit time to UK but limited payload to 110 passengers per aircraft.

20. In the event, last minute political considerations prevented some MF personnel from recovering as planned and the 3rd VC10 sortie was deferred until later in the airlift. Indeed, further enforced changes led to the cancellation of one VC10 and 6 Hercules sorties from the planned airlift and the substitution of a 2nd phase airlift in their place. Nevertheless, the overall concept of the recovery airlift was maintained and the plan proved to be sufficiently flexible to allow for these lat minute changes.

21. The offloading and loading of all recovery airlift aircraft was achieved by the 2 in-theatre MAMS teams, each of which was reinforced by 3 additional personnel for this purpose. This proved to be an ideal manning level for the workload experienced and also gave the flexibility to concurrently handle in-theatre tasks and to give assistance to Commonwealth Air Forces when required.

22. During the recovery airlift 12 VC10, 29 Hercules and 2 C5A Galaxy sorties were handled, giving a total offload/onload of 1143 passengers and 992,402 lbs of cargo.

18. The strategic recovery plan called for the recovery of non-essential vehicles by sea and the recovery of all personnel, helicopters, specialist vehicles and essential equipment by air. An element of the FCO and the Election Commission were also to be recovered by air.

19. The strategic airlift was closely tailored to meet the MP’s requirement to recover the majority of its personnel to UK on the same day they were to be recovered from Assembly Areas. Accordingly, 5 VC10s in the full passenger role were planned for the first 48 hours of the operation. These were routed inbound via Akrotiri which gave the desired short transit time to UK but limited payload to 110 passengers per aircraft.

20. In the event, last minute political considerations prevented some MF personnel from recovering as planned and the 3rd VC10 sortie was deferred until later in the airlift. Indeed, further enforced changes led to the cancellation of one VC10 and 6 Hercules sorties from the planned airlift and the substitution of a 2nd phase airlift in their place. Nevertheless, the overall concept of the recovery airlift was maintained and the plan proved to be sufficiently flexible to allow for these lat minute changes.

21. The offloading and loading of all recovery airlift aircraft was achieved by the 2 in-theatre MAMS teams, each of which was reinforced by 3 additional personnel for this purpose. This proved to be an ideal manning level for the workload experienced and also gave the flexibility to concurrently handle in-theatre tasks and to give assistance to Commonwealth Air Forces when required.

22. During the recovery airlift 12 VC10, 29 Hercules and 2 C5A Galaxy sorties were handled, giving a total offload/onload of 1143 passengers and 992,402 lbs of cargo.

CONCLUSION

23. Operation Agila was a unique and demanding but immensely rewarding experience for all those who took part in it. The UKMAMS teams based in Rhodesia operated both as a temporary air movements organization at Salisbury Airport and in their mobile role at forward airfields within Rhodesia and Southern Africa. By the end of the operation they had handled 8,356 passengers and 5,510,437 lbs of cargo.

24. In both roles the teams were often placed under pressure to complete difficult tasks in trying conditions within very strict time limits. They responded to this challenge with characteristic enthusiasm and cheerfulness and were seen to prove in an operational situation both the overall concept of MAMS operations and the value of their specialized training and experience. In doing so they provided a visible and potent argument for the retention of specialist air movements expertise both at officer and NCO level and for the maintenance of MAMS teams in their present form to meet similar contingencies worldwide at the minimum of notice.

23. Operation Agila was a unique and demanding but immensely rewarding experience for all those who took part in it. The UKMAMS teams based in Rhodesia operated both as a temporary air movements organization at Salisbury Airport and in their mobile role at forward airfields within Rhodesia and Southern Africa. By the end of the operation they had handled 8,356 passengers and 5,510,437 lbs of cargo.

24. In both roles the teams were often placed under pressure to complete difficult tasks in trying conditions within very strict time limits. They responded to this challenge with characteristic enthusiasm and cheerfulness and were seen to prove in an operational situation both the overall concept of MAMS operations and the value of their specialized training and experience. In doing so they provided a visible and potent argument for the retention of specialist air movements expertise both at officer and NCO level and for the maintenance of MAMS teams in their present form to meet similar contingencies worldwide at the minimum of notice.

by Squadron Leader Jerry Porter

Christmas was coming, the goose was on a diet and on 19th December 1979 UKMAMS was on its way to Rhodesia. The first activation elements of UKMAMS departed in the air conditioned comfort of a VC10 from Brize Norton to Salisbury.

The task was to receive a UK monitoring force in Rhodesia to oversee the handover from the current white Rhodesian government to a more democratic system. In the process the country would be renamed Zimbabwe.

For six weeks prior to the operation two teams of UKMAMS personnel were put onto standby waiting the outcome of the political wrangling before they could get started. During this time they were unable to take leave or be allocated to other tasks, effectively confining them to the MAMS crewroom at RAF Lyneham. When the call finally came to go ahead the initial elements of UKMAMS departed by VC10, whilst the remainder followed on in the C130 Hercules aircraft allocated to the task.

For six weeks prior to the operation two teams of UKMAMS personnel were put onto standby waiting the outcome of the political wrangling before they could get started. During this time they were unable to take leave or be allocated to other tasks, effectively confining them to the MAMS crewroom at RAF Lyneham. When the call finally came to go ahead the initial elements of UKMAMS departed by VC10, whilst the remainder followed on in the C130 Hercules aircraft allocated to the task.

In Rhodesia the departing government's decision to abrogate power did not enjoy the unanimous support of the entire population. There were also elements in the country that were not entirely charitable to the nominal role of the proposed government. The Rhodesians were confidently predicting trouble, and it was thought prudent to warn the British military that their aircraft ran the risk of being shot at. This meant that the normal straight in approach favoured by the passengers and all but the most gung-ho of crew flying transport aircraft had to be abandoned in favour of a more tactical approach. This manoeuvre involved turning up over the airfield at almost cruising height, and then rapidly descending in a spiral dive, before levelling out and hitting the ground, hopefully in the vicinity of the airfield.

It was because of these aggressively inclined individuals that it was deemed prudent to invite a police force to monitor the handover of power and discourage disruptive elements from becoming over vociferous during the transition. UKMAMS was tasked to outload and receive this force into Zimbabwe, and lend tone to what could otherwise become a rather vulgar episode in British military history. Despite the best efforts of our military high command there was to be no advance party pre-positioned in Rhodesia to organize the reception of the UKMAMS detachment and so it seemed that the advance party would need to be rather self sufficient. The Royal Corps of Transport did however manage to get one Major and a Warrant Officer to Rhodesia in time to organize the accommodation for the team, which couldn't have been worse. Those people familiar with the interaction between UKMAMS and the RCT will be aware that a rivalry exists which from time to time manifests itself in strongly held beliefs being expressed in a not un-physical fashion in certain Wiltshire public establishments.

The RCT made the most of this God sent opportunity, and booked the incoming MAMS team into what could only be described as a hotel by someone with an extremely generous nature. Whilst the contract and costs seemed to indicate that full board was appropriate the proprietor insisted that meal times were to be rigidly adhered to. The flying programme had not been drafted with this in mind, and the command staff taskers were strangely unwilling to delay the onset of a nations democracy to suit the wishes of a seedy hotel owner.

The RCT made the most of this God sent opportunity, and booked the incoming MAMS team into what could only be described as a hotel by someone with an extremely generous nature. Whilst the contract and costs seemed to indicate that full board was appropriate the proprietor insisted that meal times were to be rigidly adhered to. The flying programme had not been drafted with this in mind, and the command staff taskers were strangely unwilling to delay the onset of a nations democracy to suit the wishes of a seedy hotel owner.

Clearly over excited at the onset of a "one man one vote" system the proprietor put the meal issue to the vote. It was just bad luck that in this the first of Zimbabwe's democratic elections only one man cast one vote, and meals were off. The rooms although shared between four men did however boast a wide selection of en-suite facilities. The bath was an unplumbed in metal tank that would only be filled once a day by order of the management.

However this cunningly built contrivance was multi purpose. The tub without modification also doubled as a toilet, a bidet, and by waiting for someone to breath in and holding his head underwater you could relax in a quite passable Jacuzzi. It soon dawned upon the team that something had to be done about the accommodation.

When taking a bath it was preferable to be first as the water would be cleanest, and if fortunate, might well be slightly above ambient room temperature. By the same token it was imperative to lay claim to this facility before those wishing to relieve themselves as although the water would be slightly warmer, washing was a more hazardous exercise. Of course the later down the bathing list you were the more filthy the water became.

However this cunningly built contrivance was multi purpose. The tub without modification also doubled as a toilet, a bidet, and by waiting for someone to breath in and holding his head underwater you could relax in a quite passable Jacuzzi. It soon dawned upon the team that something had to be done about the accommodation.

When taking a bath it was preferable to be first as the water would be cleanest, and if fortunate, might well be slightly above ambient room temperature. By the same token it was imperative to lay claim to this facility before those wishing to relieve themselves as although the water would be slightly warmer, washing was a more hazardous exercise. Of course the later down the bathing list you were the more filthy the water became.

At the time this was considered to be a deliberate manifestation of a new country's first democratic policy. Its intended goal seemed to hinge on making the whole population the same colour, removing once and for all the last hint of colour prejudice. The hotel also boasted a laundry service that could return half of your washing within forty eight hours. No one found out exactly what had happened to the teams other 50%, but no doubt it found its way into the local economy.

Alerted to the fact that his troops were getting thin, (as well as dirty) and were in danger of panicking locals into thinking that widespread famine was imminent, the boss despatched a reconnaissance team into town to seek out a more advanced civilization. As the old maxim states that "time spent in reconnaissance is seldom time wasted" and the team were gratified to find a much better prospect. The new hotel had single rooms, provided a round the clock catering service, had a free to residents disco, and a swimming pool. All this and for only half the price of the original Stalag. Being on an imprest (which is a large sum of money freely given to cover expenses) the team enjoyed a certain independence and payment would not be a problem. MAMS duly went up-market.

Alerted to the fact that his troops were getting thin, (as well as dirty) and were in danger of panicking locals into thinking that widespread famine was imminent, the boss despatched a reconnaissance team into town to seek out a more advanced civilization. As the old maxim states that "time spent in reconnaissance is seldom time wasted" and the team were gratified to find a much better prospect. The new hotel had single rooms, provided a round the clock catering service, had a free to residents disco, and a swimming pool. All this and for only half the price of the original Stalag. Being on an imprest (which is a large sum of money freely given to cover expenses) the team enjoyed a certain independence and payment would not be a problem. MAMS duly went up-market.

The airlift commenced using our own VC10 and Hercules aircraft. As capable as these aircraft were they could not quite cope with the armoured land rovers and larger helicopters that needed to be airlifted into theatre. To assist in this the USAF came to our rescue with their C5 and C141 aircraft with the greater carrying capacity that they offered.

The RCT movers were also in theatre, as a liaison between the Army and the RAF. This is quite natural as the Army don't understand airplanes, and the RAF find it difficult to understand the grunts that the Army make in place of normal speech. The RCT do not understand even the simplest of concepts, and are therefore used as interpreters between blue and brown. Since arriving the RCT had not been idle (a novel state of affairs) and had erected a charming blue and white "stripy" tent which was to become the reception area for incoming loads. Once you have put up a tent it is human nature for its owners to feel duty bound to loiter within its confines as if to justify its existence. The RCT are no exception to this rule and, after a memorable communiqué to the corridors of power back in the UK the phrase "loitering with intent" passed into common usage.

The RCT movers were also in theatre, as a liaison between the Army and the RAF. This is quite natural as the Army don't understand airplanes, and the RAF find it difficult to understand the grunts that the Army make in place of normal speech. The RCT do not understand even the simplest of concepts, and are therefore used as interpreters between blue and brown. Since arriving the RCT had not been idle (a novel state of affairs) and had erected a charming blue and white "stripy" tent which was to become the reception area for incoming loads. Once you have put up a tent it is human nature for its owners to feel duty bound to loiter within its confines as if to justify its existence. The RCT are no exception to this rule and, after a memorable communiqué to the corridors of power back in the UK the phrase "loitering with intent" passed into common usage.

Once the RCT had settled in and realized that contrary to all expectations they were neither mentally or physically exhausted by the tent erection, they became quite adventurous. It soon became evident that they thought they should have control of the aircraft handling-area at Salisbury airport. Only after prolonged arguments did they concede that their territory began at the edge of the aircraft handling area. This blue/brown demarcation philosophy was rigorously enforced by the RAF movers by the simple expedient of driving the MAMS vehicles at high speed towards any RCT personnel who deliberately or inadvertently transgressed the divide. And so it was in the spirit of co-operation so characteristic of joint operations that a larger potential territorial dispute was to be averted by troops bitterly engaged in a more minor one of their own.

Salisbury airport is divided into halves. One half was allocated to the civil air transport world, whilst the other, called New Sarum, was given over to the Rhodesian Air Force. The former of the two was running alive with charming stewardesses and luxurious facilities, we of course got the latter. Many of the arriving troops were due to be flown up country shortly after arriving in Zimbabwe, and whilst we loaded the freight in the military side the passengers were processed through the civil side. Often the mighty Hercules would, once loaded, have to taxi across the airfield to the main terminal to collect its passengers relegating the pilots to the role of a taxi driver (confirming a suspicion that we had entertained for some time).

Salisbury airport is divided into halves. One half was allocated to the civil air transport world, whilst the other, called New Sarum, was given over to the Rhodesian Air Force. The former of the two was running alive with charming stewardesses and luxurious facilities, we of course got the latter. Many of the arriving troops were due to be flown up country shortly after arriving in Zimbabwe, and whilst we loaded the freight in the military side the passengers were processed through the civil side. Often the mighty Hercules would, once loaded, have to taxi across the airfield to the main terminal to collect its passengers relegating the pilots to the role of a taxi driver (confirming a suspicion that we had entertained for some time).

During the lift we were handling our aircraft and the American monstrosities as well as civilian charter flights hired to the airlift At times we had more aircraft than MAMS personnel - a situation that I feel will never change... it's called planning.

Not only were we responsible for loading the aircraft at Salisbury, but we were also responsible for accompanying the flights "up country" to complete the off- loads at the unit being moved's designated location. To accomplish this we split the team into two halves, and then further subdivided one half into two man teams who were to deliver and de-plane the loads. We handled the airland side of the operation whilst 47 Air Despatch RCT managed the airdrop sorties. Air land operations on the sort of strips found up country are very taxing on the aircraft, and recurrent unserviceabilities were not uncommon.

Not only were we responsible for loading the aircraft at Salisbury, but we were also responsible for accompanying the flights "up country" to complete the off- loads at the unit being moved's designated location. To accomplish this we split the team into two halves, and then further subdivided one half into two man teams who were to deliver and de-plane the loads. We handled the airland side of the operation whilst 47 Air Despatch RCT managed the airdrop sorties. Air land operations on the sort of strips found up country are very taxing on the aircraft, and recurrent unserviceabilities were not uncommon.

This meant that the aircraft configured for airdrop fared far better than those used for airland. It was therefore inevitable that to achieve the task we had to hijack the odd aircraft and indulge in some very imaginative aircraft reroling which unfortunately took a heavy toll on the nerves of the Air Load Master fraternity. It is prudent to mention at this stage that the role of the ALM centres around the production of coffee for the rest of the crew, a job that occupies the bulk of their time and intellectual capacity. Not noted for their in depth knowledge of aircraft loading, they tend to stick to the rules.

Roles to the aircraft that do not appear in the many publications available to them on the aircraft are guaranteed to bring them to a state of near panic. The flying profiles of the Hercs were adopted to reduce the risk of damage to the aircraft and danger to those on it This involved flying at very high altitude to out distance any ground fire directed upwards, or at very low level to conceal the approach of the aircraft from any unfriendly intent on the ground. When flying at altitude any depressurisation of the aircraft (commonly caused by the Air Engineer falling into a caffeine induced coma onto the switch concerned with such things) generates the requirement for oxygen. On the Hercules oxygen is carried in its liquid state (LOX) to save space, and apart from being cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass loadmaster it is extremely volatile when brought into contact with grease or oil. Now by quirk of fate the average transport aircraft is liberally coated in both substances.

Roles to the aircraft that do not appear in the many publications available to them on the aircraft are guaranteed to bring them to a state of near panic. The flying profiles of the Hercs were adopted to reduce the risk of damage to the aircraft and danger to those on it This involved flying at very high altitude to out distance any ground fire directed upwards, or at very low level to conceal the approach of the aircraft from any unfriendly intent on the ground. When flying at altitude any depressurisation of the aircraft (commonly caused by the Air Engineer falling into a caffeine induced coma onto the switch concerned with such things) generates the requirement for oxygen. On the Hercules oxygen is carried in its liquid state (LOX) to save space, and apart from being cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass loadmaster it is extremely volatile when brought into contact with grease or oil. Now by quirk of fate the average transport aircraft is liberally coated in both substances.

Therefore it is in everyone's best interests to keep the LOX firmly enclosed in its specially degreased container. It was therefore understandably the cause of some consternation to find on return from one sortie that Hercules XV 176 had acquired a bullet hole in the nose wheel bay perilously close to the LOX tank. This bullet hole was attributed to Mozambique rebels (although who could be certain) who were one of the groups objecting to the hand over of power. XV 176 was thereafter nicknamed "Flack Alice", and working on the assumption that it is better to suffocate than be blown to bits LOX was no longer carried. This local decision pleased the air staff who were of the opinion that it would be disastrous to lose an aircraft to enemy action and the inevitable disgrace and questioning of our military capabilities that this would cause. Far better to announce if we did lose one of our Hercs, that the crew, absorbed with flying the aircraft had simply forgotten to breathe. The defence of our aircraft flying over what could often be hostile territory was a subject taken very seriously.

In response to a perceived threat from the heat seeking anti aircraft SAM 7 missile believed to be in the hands of the rebels the RAF came up with a high-tech counter measure solution. On nights regarded as "at risk" the MAMS personnel accompanying the load were required to sit on the open ramp at the back of the aircraft. Armed with the distress flare pistol standard on our aircraft, the unfortunate mover was further instructed to watch out for in coming missiles, and on discovery fire the flare pistol at it The flare it was hoped would distract the missile by confusing it into believing it to be not a flare but an aircraft engine. The rebels didn't stand a chance.

In response to a perceived threat from the heat seeking anti aircraft SAM 7 missile believed to be in the hands of the rebels the RAF came up with a high-tech counter measure solution. On nights regarded as "at risk" the MAMS personnel accompanying the load were required to sit on the open ramp at the back of the aircraft. Armed with the distress flare pistol standard on our aircraft, the unfortunate mover was further instructed to watch out for in coming missiles, and on discovery fire the flare pistol at it The flare it was hoped would distract the missile by confusing it into believing it to be not a flare but an aircraft engine. The rebels didn't stand a chance.

MAMS suffered a keenly felt loss on Christmas day, when their ingeniously purloined Christmas tree complete with makeshift decorations, had been stolen from outside their office. The Americans entered into the spirit of the season by observing a national holiday over Christmas, possibly believing that they were still in Vietnam.

Once the initial rush to get everything in position was over the emphasis switched to the much less demanding regime of resupplying the forces already out there. Things settled down and as innovative thinking overcame shortages and inadequate facilities the remainder of the operation became routine. During this period a severe shortage of food was encountered in the holding area. UKMAMS were tasked with the out load of food from Lingerie and Jan Smuts, both near Johannesburg, South Africa, direct to the holding areas such as Beltway, Fort Victoria, Lemma, Grand Reef and Keota. In some of the hardest work of the entire operation UKMAMS teams flew many sorties carrying freshly butchered and frozen meat. Other sorties included peanuts and stinking dried fish direct from Salisbury itself. However, much to the gratitude of the local populace the task was completed quickly and efficiently, and another potentially destabilising situation was avoided. Shortly after the MAMS team were relieved of their impress (a state of affairs viewed with the same feelings as the loss of a close relative) with contract catering and accommodation becoming the order of the day.

Once the initial rush to get everything in position was over the emphasis switched to the much less demanding regime of resupplying the forces already out there. Things settled down and as innovative thinking overcame shortages and inadequate facilities the remainder of the operation became routine. During this period a severe shortage of food was encountered in the holding area. UKMAMS were tasked with the out load of food from Lingerie and Jan Smuts, both near Johannesburg, South Africa, direct to the holding areas such as Beltway, Fort Victoria, Lemma, Grand Reef and Keota. In some of the hardest work of the entire operation UKMAMS teams flew many sorties carrying freshly butchered and frozen meat. Other sorties included peanuts and stinking dried fish direct from Salisbury itself. However, much to the gratitude of the local populace the task was completed quickly and efficiently, and another potentially destabilising situation was avoided. Shortly after the MAMS team were relieved of their impress (a state of affairs viewed with the same feelings as the loss of a close relative) with contract catering and accommodation becoming the order of the day.

On the positive side the MAMS team were welcomed as temporary members of the Royal Salisbury golf club. Life continued in this relatively relaxed vein until the country came to the actual handover of power. With this came the necessity of repatriating the Mozambique rebels whose presence was not wholly welcome or politically significant. In the interests of the British tax payer the government decided to save fuel and accomplish this in the least possible number of lifts. With the proud Hercs looking like the inside of a Thompson sunshine holiday charter special, rebels were given new tee-shirts before being packed to the gunwales and flown home. The new shirts was an idea that the British had to avoid the rebels displaying any heroic or inflammatory clothing and thus inspiring further rebellion.

One final moment of media fame came to UKMAMS when they were seen by the viewing public receiving and moving up country British policemen who were sent to Zimbabwe to police the elections. The West Midlands serious crime squad were heavily involved, although an impartial observer might consider that many ballot papers were little improved by the signed confessions that had mysteriously appeared on each one.

One final moment of media fame came to UKMAMS when they were seen by the viewing public receiving and moving up country British policemen who were sent to Zimbabwe to police the elections. The West Midlands serious crime squad were heavily involved, although an impartial observer might consider that many ballot papers were little improved by the signed confessions that had mysteriously appeared on each one.

And so with the water slowly ebbing from another tide of British military history, UKMAMS were once again at the forefront of another significant chapter in the world’s political history. Whilst armed only with nine inches of polished pine the British police marshalled Zimbabwe's first elections. Their steadying influence is of course a matter of historical record.

Less well known to the British public is the vast number of air sickness bags that were used flying the "thin blue line" at low level to the polling stations. UKMAMS were eventually brought home and apart from the memories of a most unusual task, they brought with them an umbrella stand, and a large "Sunshine City" sign that now reposes in the UKMAMS crew room at RAF Lyneham.

Less well known to the British public is the vast number of air sickness bags that were used flying the "thin blue line" at low level to the polling stations. UKMAMS were eventually brought home and apart from the memories of a most unusual task, they brought with them an umbrella stand, and a large "Sunshine City" sign that now reposes in the UKMAMS crew room at RAF Lyneham.