Following yet another particularly poor harvest, it came to the world's attention that the people of Ethiopia were suffering a famine of biblical proportions. This was of course nothing new to the population of the region who have suffered the ravages of an infertile ecology for countless generations. The difference in the late summer of 1984 lay with a growing global awareness of the problems that these people faced. Members of Parliament responded positively to a Red Cross request for assistance and tasked an RAF Hercules with UKMAMS support to aid with relief operations in the region.

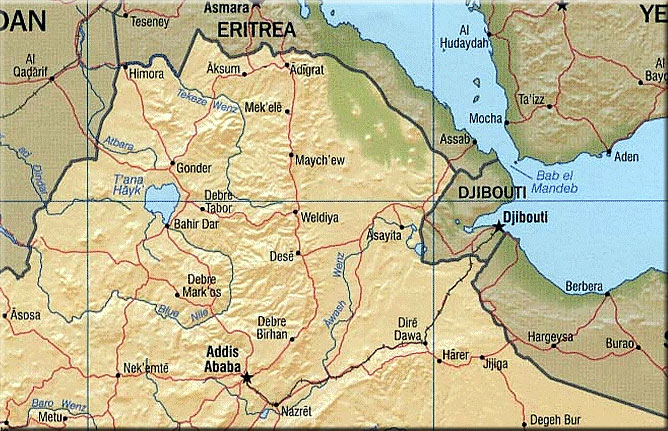

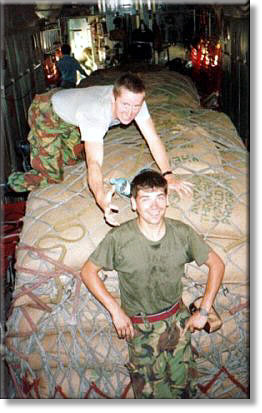

On November 3rd, 1984, three UKMAMS teams arrived in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa and were the first movers to arrive in-theatre for what became known as Operation Bushel. The MAMS team set up a tented camp site in the grounds of the British Embassy compound. Within three hours of arrival, the teams were fully operational and at 0700 hrs on 4th November the first British missions were launched. Prior to the RAF arrival in Addis Ababa, relief goods from around the world had been arriving into the Red Sea port of Assab. Professional relief agencies had set up two feeding stations; one in Mekele and the other in Axum. The role of the RAF was to fly the relief goods from Assab to the two feeding centres where the relief workers would distribute the food to the starving who were being assembled there. MAMS placed four men on each aircraft to accompany the goods to their destinations, whilst maintaining detachments at both Assab and Addis Ababa. These two detachments were there top coordinate the reception of the aid into the country, and supervise its transport to the air head at Addis Ababa, whilst the team at the air head were there to receive the supplies from Assab and brigade them into aircraft loads.

The work was arduous for the teams. The heat was stifling and virtually everyone was sick with "Selassie's Revenge." Despite the conditions, the teams managed to launch three sorties daily averaging 200,000 lbs of grain to the forward feeding locations. The importance of these figures is more readily appreciated when one considers that just 20 lbs of grain will feed one man for a month. Each day's airlift was feeding 300,000 people for the day.

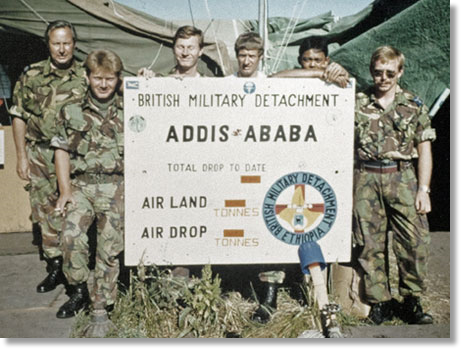

The British Military Detachment came under the operational control of the Ethiopian Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC). Manned by Ethiopians, the RRC controlled the entire aid programme, and coordinated the activities of the numerous aid agencies operating within Ethiopia - an enormous and complicated task, but the RRC did sterling work.

The MAMS team then built the allocated freight into viable aircraft loads, loaded the airframes and dispatched it to the target location. Travelling with the load, the team then offloaded the aircraft before returning for the next shuttle. At both ends the teams were working with the local population and were required to tailor their normal working practices to accommodate local procedures. The relief agency workers and locally conscripted help were often unaccustomed to the kevel of physical work often endured by the "Muppets". This shouldn't be seen as a statement of self praise or unstinting sacrifice, rather as an advert for the advantages of being reasonably young, medically well cared for and enjoying the benefits of a substantial diet.

In order to ensure the smooth running of the operation it was obvious that the disparity in working rates would have to be addressed. The MAMS teams reverted to coercion, persuasion and even bribery to achieve the task. With a tremendous spirit of cooperation and good will, the composite teams of UKMAMS and local help were achieving aircraft turnarounds of fifteen minutes. This is quite a remarkable feat considering that the average load could have upwards of 42,000 lbs of grain in 110 lb sacks, all of which had to be manhandled on and off the aircraft. A far easier way would have been to palletize the loads, but this would have required an investment in handling equipment at all locations that would have been impossible - moreover, local labour was plentiful.

Like most operations of this nature, the teams were working at a rate designed to accommodate the backlog that had built up prior to the start. It wasn't long before the British had cleared the supplies and were short of relief goods to make up loads for the British aircraft. Equally important in such circumstances is the maintenance of momentum, and to slow the pace down is not only anti-climatic, but can be disastrous. To keep the sense of challenge alive, there then followed a period when the MAMS teams resorted to acquiring loads in an unconventional fashion. Bole International Airport in Ethiopia was another nearby reception centre for the world wide relief effort. Whilst not in the UKMAMS geographically assigned area of operations, Bole was subject to the clandestine removal of large amounts of relief goods. These goods were loaded to our aircraft and then spirited up-country courtesy of the British detachment. This was only necessary as a temporary measure and after a while the allocation of supplies was gradually increased to meet the British capacity to move it. This is a justifiably proud claim that by maintaining the pressure on the RRC to allocate the goods, UKMAMS were able to fly supplies forward every single day of the detachment, including Christmas day.

For three months, airland operations continued ferrying the supplies. It was becoming increasingly obvious that the landing strips were not universally accessible to the population requiring help. To meet this fresh challenge, one of the two aircraft involved in the operation was re-roled for airdrop sorties. This meant that the food could now be flown directly to the population, obviating the need for them to travel to a landing strip for it. This also gave the aid workers on the ground a much greater degree of flexibility, and enabled them to keep the encampments smaller, thus reducing the risk of epidemic.

The airdrop option would also reduce the pressure on UKMAMS as the air dispatch is a job normally carried out by the Army. Without the necessity to unload both aircraft, the UKMAMS detachment was reduced to just 12 men. In addition to enabling relief supplies to reach a much wider area, this development also gave the British press a more dramatic photo opportunity.

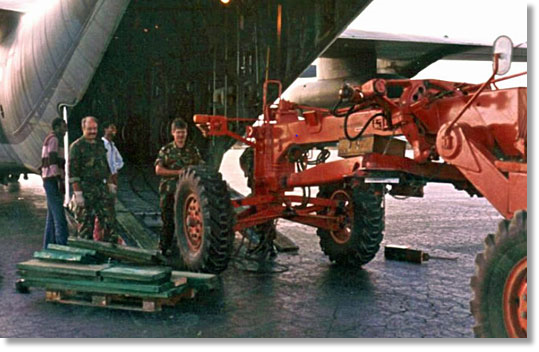

The MAMS teams were not only responsible for handling our own Hercules aircraft, in addition they worked on VC-10's, TriStars, DC-10's, Luftwaffe C160's Belfast's and Boeing 707's. Neither did they only have to move food - earth moving vehicles, road rollers and graders were all airlifted into the famine area along with the grain, rice and high protein foods. Clothing and tentage were also flown into the area, following national appeals for such items as they became necessary.

UKMAMS were also made responsible for the delivery of a pre-fabricated hospital (of Italian origin) into the stricken area. This was airlifted in on 16th December 1985 much to the relief of the Ethiopians who desperately needed it, and likewise the Italian Government who, having had it made, had no idea of how to get it to where it was needed.

As Operation Bushel drew to a close, UKMAMS planned and executed the withdrawal of all British personnel and equipment used in the operation. Last out as usual, the UKMAMS detachment took off from Addis Ababa on 19th December 1985 bringing to a close a chapter in the history of the squadron that will always be regarded with pride. No one who was there could fail to be moved by the plight of the people that they had gone to help. Those that took part, and the squadron as a whole, share a deep sense of honour that they were privileged to be involved. From those efforts, Britain's contribution was a major factor in the success of the world wide operation. In just over a year, UKMAMS moved 1,000 personnel and 40,000,000 lbs of relief supplies to help save a nation.

The RRC working closely with, and often seeking the advice of, the MAMS detachment, allocated the order in which the supplies were to be outloaded, and detailed the areas to which they were to be flown.

SAC 'Pig' Clarke and an unnamed L/Cpl from 9 Para RE. Dec. 1984. Here we have 3 stacks of powdered milk, each over 10K

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1985

Left to right Terry Roberts, Angus Boyce, Kit Kitson,

Geordie Rochester, Eddie Sundarajoo, John Belcher

Left to right Terry Roberts, Angus Boyce, Kit Kitson,

Geordie Rochester, Eddie Sundarajoo, John Belcher

Gerry Moffet and Derek Barron offloading an earthmover

C-130 Hercules making a low-altitude drop of relief supplies