Wrapping up Saif Sareea III for Christmas

Since 1966, UKMAMS/1 AMW has been the ‘First In, Last Out’ of every major operation and exercise requiring the enablement of air transport activity. Most recently, Exercise Saif Sareea III, a combined British and Omani military exercise, was no different.

The whole process brought unique challenges including the first double Puma helicopter move with an Air Transportable Galley/Lavatory (ATGL) and the first Chinook with an ATGL move on a C-17 as well as the diversion to the airbridge of mission critical equipment originally destined to travel by sea.

After the other tri-service enabling groups had left the country in early December, a contingent of UK Mobile Air Movements Squadron personnel remained to process, build, prepare, load and despatch the outstanding exercise freight. Five days before Christmas the last Saif Sareea III presence in country departed on an A400M bound for the UK - displaying that after 52 years they are still the ‘First In, Last Out’.

Royal Air Force

The whole process brought unique challenges including the first double Puma helicopter move with an Air Transportable Galley/Lavatory (ATGL) and the first Chinook with an ATGL move on a C-17 as well as the diversion to the airbridge of mission critical equipment originally destined to travel by sea.

After the other tri-service enabling groups had left the country in early December, a contingent of UK Mobile Air Movements Squadron personnel remained to process, build, prepare, load and despatch the outstanding exercise freight. Five days before Christmas the last Saif Sareea III presence in country departed on an A400M bound for the UK - displaying that after 52 years they are still the ‘First In, Last Out’.

Royal Air Force

From: Ian Stacey, Nashville, IN

Subject: The Early Years - a tad late!

Hi Tony,

As you know I have recently moved from Illinois to Indiana and I am still in the throes, six months later, of unpacking boxes and trying to find all the unnecessary stuff that we keep from years gone by. I had intended to try and send you the attached picture for your edition of “The Early Years” but could not find it. Well, it just turned up and I am belatedly sending it to you in case you can still use it.

Subject: The Early Years - a tad late!

Hi Tony,

As you know I have recently moved from Illinois to Indiana and I am still in the throes, six months later, of unpacking boxes and trying to find all the unnecessary stuff that we keep from years gone by. I had intended to try and send you the attached picture for your edition of “The Early Years” but could not find it. Well, it just turned up and I am belatedly sending it to you in case you can still use it.

This a caricature of me done at Abingdon in 1965 by the cartoonist Pat Rooney. Rooney was quite a well-known artist in his time and was mostly known for his drawings of RAF personnel during WW2. It is not difficult to find his drawings on the internet and if you do a search for these, most of them are WW2 vintage. He died in 1966 at age 82 so must have been 81 when he did this of me. I found an article about him on the internet which explains:

“By the time war broke out in 1939 Rooney would have been fifty-five and was much in demand by members of the armed forces, travelling by train to RAF stations in particular. He would seek permission of the manager of the Officer’s Mess before setting-up shop, his first “commission” would probably cost nothing in order to generate interest and he would proceed then to produce “lightning” sketches, each taking five minutes or so and, for some reason, usually of the sitter’s left profile. The charge would be five shillings or seven-and-sixpence if a frame with passé-partout and glass was required."

Anyway – as you can see, Rooney has captured me at one of our favorite occupations of the time – downing a pint or two!!

He also added a couple of Blackburn Beverley’s in the picture and, if you look carefully, a couple of forklift trucks since I had told him that I was in Air Movements.

“By the time war broke out in 1939 Rooney would have been fifty-five and was much in demand by members of the armed forces, travelling by train to RAF stations in particular. He would seek permission of the manager of the Officer’s Mess before setting-up shop, his first “commission” would probably cost nothing in order to generate interest and he would proceed then to produce “lightning” sketches, each taking five minutes or so and, for some reason, usually of the sitter’s left profile. The charge would be five shillings or seven-and-sixpence if a frame with passé-partout and glass was required."

Anyway – as you can see, Rooney has captured me at one of our favorite occupations of the time – downing a pint or two!!

He also added a couple of Blackburn Beverley’s in the picture and, if you look carefully, a couple of forklift trucks since I had told him that I was in Air Movements.

I loved working with the Beverly’s, they were great aircraft. We had 47 squadron at Abingdon at that time and in the mess we were friends with many of the crew members, one of the captains, Jim Young, used to describe his Beverly as “50,000 rivets in loose formation!” Also, since the Beverly had a fixed undercarriage Jim used to love to tease air traffic controllers at other stations un-familiar with them. On final landing approach his response to the familiar call of “Finals – three greens” (3 green lights meaning that most retractable undercarriages were lowered) was “Undercarriage down and welded!”

Great days – weren’t we lucky to be there!

Cheers, Ian

Great days – weren’t we lucky to be there!

Cheers, Ian

Belated and Misplaced Christmas Messages

During the rush to get the Christmas newsletter out on time, I missed a few messages, plus there were some late arrivals, so here they are:

From: Stan Seggar, Sheffield

Subject: Christmas Greetings

Hi Tony,

All the best to you and all other ex Boy Entrants of C Flt, 3 Sqn, 50th Entry Suppliers, RAF Hereford 1963/65

Merry Christmas to all.

Stan Seggar (1949857)

Subject: Christmas Greetings

Hi Tony,

All the best to you and all other ex Boy Entrants of C Flt, 3 Sqn, 50th Entry Suppliers, RAF Hereford 1963/65

Merry Christmas to all.

Stan Seggar (1949857)

From: Howard Thomas, Caravonica, QLD

Subject: Christmas Greetings

Subject: Christmas Greetings

Pictured together for the first time in 28 years are Taff (Tony) Weale and his partner Wendy on a visit to Cairns, Australia with Howard (Thommo) Thomas and his missus Bronwyn.

We served on Air Movs at BZZ in 1980 - some 38 years ago. As with all good service friendships, within five minutes we were back in the crew room telling stories and laughing at times past!

Merry Xmas to you all.

Howard & Bronwyn

We served on Air Movs at BZZ in 1980 - some 38 years ago. As with all good service friendships, within five minutes we were back in the crew room telling stories and laughing at times past!

Merry Xmas to you all.

Howard & Bronwyn

From: Keith Simmonds, Nottingham

Subject: Christmas Greetings

Sorry, but I can't find a suitable picture - having a bit of a tough time at the moment with a sickness in the family. I met Merv Corke last week in Swindon - he's 88 now.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to all.

Keith

Subject: Christmas Greetings

Sorry, but I can't find a suitable picture - having a bit of a tough time at the moment with a sickness in the family. I met Merv Corke last week in Swindon - he's 88 now.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to all.

Keith

From: Basil Hughes, Pattaya

Subject: Greetings

Merry Christmas and a happy New Year to you and all the MAMS Family. Love and greetings from us all here in Thailand

Bas

Subject: Greetings

Merry Christmas and a happy New Year to you and all the MAMS Family. Love and greetings from us all here in Thailand

Bas

From: Neil Collie, Canberra, ACT

Subject: New Year Messages

Bugger! Missed the Xmas messages and note that OBie (RAAF) got one in! Anyway, Happy New Year to RAF and RAAF Movers everywhere. OK, even the RNZAF Movers, even Dave Milne.... just!

Cheers

Neil Collie

Subject: New Year Messages

Bugger! Missed the Xmas messages and note that OBie (RAAF) got one in! Anyway, Happy New Year to RAF and RAAF Movers everywhere. OK, even the RNZAF Movers, even Dave Milne.... just!

Cheers

Neil Collie

Wessex Helicopter Touchdown at Crumlin Road Gaol

Yesterday evening, January 13th., Crumlin Road Gaol in Belfast took delivery of a decommissioned Westland Wessex helicopter from RAF Aldergrove. The Wessex XR 529 ‘ECHO’ will be the focal point of a new tour being launched at the 5-star visitor attraction in 2019.

Carefully guided into placed beside the Sanger at D Wing, the helicopter will be on display to visitors. It will give them an insight into the happenings during the conflict in Northern Ireland and tell the story which the British Army and RAF played both at the jail and in the wider community.

Once an iconic feature of the skyline in Northern Ireland, the helicopter was part of a batch of 30 HC2s built by Westland Aircraft Ltd. They were operated by 72 Squadron at RAF Aldergrove until 2002. 72 Squadron served in an Army support role and the Wessex was used as troop carrier for up to 16 passengers. It was decommissioned and displayed as the RAF Aldergrove Gate Guardian on 16th May 2003.

Phelim Devlin, Director at Crumlin Road Gaol commented “After several months of planning we are excited to finally see the Wessex arrive at Crumlin Road Gaol. The Wessex Helicopter will play an important part in the next phase of development at the jail.”

Carefully guided into placed beside the Sanger at D Wing, the helicopter will be on display to visitors. It will give them an insight into the happenings during the conflict in Northern Ireland and tell the story which the British Army and RAF played both at the jail and in the wider community.

Once an iconic feature of the skyline in Northern Ireland, the helicopter was part of a batch of 30 HC2s built by Westland Aircraft Ltd. They were operated by 72 Squadron at RAF Aldergrove until 2002. 72 Squadron served in an Army support role and the Wessex was used as troop carrier for up to 16 passengers. It was decommissioned and displayed as the RAF Aldergrove Gate Guardian on 16th May 2003.

Phelim Devlin, Director at Crumlin Road Gaol commented “After several months of planning we are excited to finally see the Wessex arrive at Crumlin Road Gaol. The Wessex Helicopter will play an important part in the next phase of development at the jail.”

He continued, “2019 will see the launch of a brand new tour at Crumlin Road Gaol which will cover all aspects of the more recent history here at this site and in the local area, including the insights from security services, loyalist and republican sides. This tour will provide an enhanced visitor experience at our 5 star visitor attraction in addition to contributing and enriching the growing tourism industry here in Belfast.”

RAF Northern Ireland Community Relations Officer, Wing Commander Tara Scott, said: “At the end of the Royal Air Force’s centenary year, we are pleased that the Wessex is moving to a new home where it will be on display to the public. Visitors will have the opportunity to learn the history of a helicopter that served the RAF for over 40 years from 1961 to 2002 including in a search and rescue role.”

lovebelfast.co.uk

RAF Northern Ireland Community Relations Officer, Wing Commander Tara Scott, said: “At the end of the Royal Air Force’s centenary year, we are pleased that the Wessex is moving to a new home where it will be on display to the public. Visitors will have the opportunity to learn the history of a helicopter that served the RAF for over 40 years from 1961 to 2002 including in a search and rescue role.”

lovebelfast.co.uk

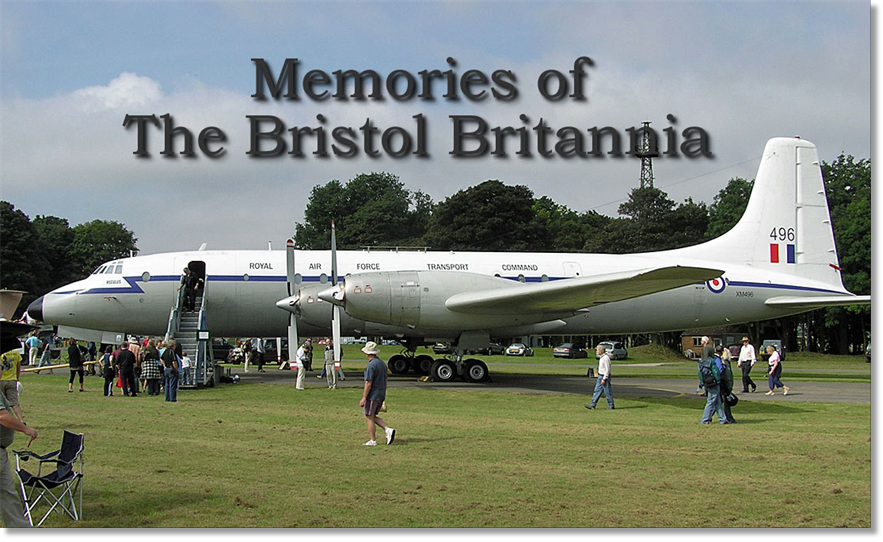

The Bristol Britannia

The Bristol Type 175 Britannia was a British medium-to-long-range airliner built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company in 1952 to fly across the British Empire. During development two prototypes were lost and the turboprop engines proved susceptible to inlet icing, which delayed entry into service while solutions were sought.

By the time development was completed, "pure" jet airliners from France, United Kingdom and the United States were about to enter service, and consequently, only 85 Britannias were built before production ended in 1960. Nevertheless, the Britannia is considered one of the landmarks in turboprop-powered airliner design and was popular with passengers. It became known as "The Whispering Giant" for its quiet exterior noise and smooth flying, although the passenger interior remained less tranquil.

Canadair purchased a licence to build the Britannia in Canada, adding another 72 variants. These were the stretched Canadair CL-44/Canadair CC-106 Yukon, and the greatly modified Canadair CP-107 Argus maritime patrol aircraft.

Wikipedia

By the time development was completed, "pure" jet airliners from France, United Kingdom and the United States were about to enter service, and consequently, only 85 Britannias were built before production ended in 1960. Nevertheless, the Britannia is considered one of the landmarks in turboprop-powered airliner design and was popular with passengers. It became known as "The Whispering Giant" for its quiet exterior noise and smooth flying, although the passenger interior remained less tranquil.

Canadair purchased a licence to build the Britannia in Canada, adding another 72 variants. These were the stretched Canadair CL-44/Canadair CC-106 Yukon, and the greatly modified Canadair CP-107 Argus maritime patrol aircraft.

Wikipedia

From: Christopher Briggs, Coventry, West Midlands

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

My first encounter with the aircraft was when the Tutankhamun exhibition arrived in a Britannia at Brize. Someone had to guard it overnight and of course I was volunteered. I can honestly say it was the most chilling experience I have ever had; very creepy and eerie.

Secondly, I recall having to fly to Gibraltar on the Britannia to help the resident movers unload/load the scheduled aircraft. It was great as I was on the flight deck there and back. On approach to Gib the aircraft was bouncing about like a good one, then noticing that we were half way down the runway and not landing the pilot said we would have to go around again. If you remember it was when the airspace around Gib was limited so a very tight left hand turn was made. I still think it looked as if the wings were touching the water! Needless to say, on the second attempt we made it - just.

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

My first encounter with the aircraft was when the Tutankhamun exhibition arrived in a Britannia at Brize. Someone had to guard it overnight and of course I was volunteered. I can honestly say it was the most chilling experience I have ever had; very creepy and eerie.

Secondly, I recall having to fly to Gibraltar on the Britannia to help the resident movers unload/load the scheduled aircraft. It was great as I was on the flight deck there and back. On approach to Gib the aircraft was bouncing about like a good one, then noticing that we were half way down the runway and not landing the pilot said we would have to go around again. If you remember it was when the airspace around Gib was limited so a very tight left hand turn was made. I still think it looked as if the wings were touching the water! Needless to say, on the second attempt we made it - just.

Thirdly was a flight out to and back from Masirah via Akrotiri. Such a quiet aircraft for its time, of course suitably named the Whispering Giant. I'll always remember the doors being opened on arrival at Masirah - the temperature inside the aircraft was nice and cool, but once the passenger door opened it was a sweltering 40ºC!

Who could forget the Britannia Freight Lift Platform (BFLP), what a nightmare that was! I could probably go on and on about the Britannia; a good old work horse that never seemed to let us down.

Cheers,

Chris B

Who could forget the Britannia Freight Lift Platform (BFLP), what a nightmare that was! I could probably go on and on about the Britannia; a good old work horse that never seemed to let us down.

Cheers,

Chris B

From: Gerry Davis, Bedminster

Subject: The Whispering Giant

Subject: The Whispering Giant

My time as an Air Mover, during the 60’s, is full of memories of working on the Britannias. I reckon I must have sweated on all of them, including the early ones without the freight door.

I recall some of the problems we encountered loading them. You had to be aware of the wind speed before opening the freight door. There were often difficulties in getting the ‘D’ rings into the floor especially if the previous load had been dusty.

If you were lucky you might have had a BFLP to help load the freight, either loose loaded or on pallets and of course vehicles. Not forgetting the workhorse of the Movers, the 12000lb fork lift.

I recall some of the problems we encountered loading them. You had to be aware of the wind speed before opening the freight door. There were often difficulties in getting the ‘D’ rings into the floor especially if the previous load had been dusty.

If you were lucky you might have had a BFLP to help load the freight, either loose loaded or on pallets and of course vehicles. Not forgetting the workhorse of the Movers, the 12000lb fork lift.

Above is a photo of a BFLP in use during the ‘Oil Lift’ which I spent 6 months in Nairobi on detachment during 1965/6. This was when Ian Smith declared Independence in Rhodesia. This machine was ‘Air portable’ when through sweat and toil it was disassembled.

There was of course a trim sheet to be filled out, in three copies, a red, blue and black one.

I also spent many an hour as a passenger flying between destinations, often having to offload it when we arrived. My three years on NEAF MAMS and the 3 years on shift at Lyneham, as the loading team corporal, fine-tuned me into the wonders of this long gone ‘Whispering Giant.’

Gerry Davis

There was of course a trim sheet to be filled out, in three copies, a red, blue and black one.

I also spent many an hour as a passenger flying between destinations, often having to offload it when we arrived. My three years on NEAF MAMS and the 3 years on shift at Lyneham, as the loading team corporal, fine-tuned me into the wonders of this long gone ‘Whispering Giant.’

Gerry Davis

From: Charles Gibson, Monifieth, Angus

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

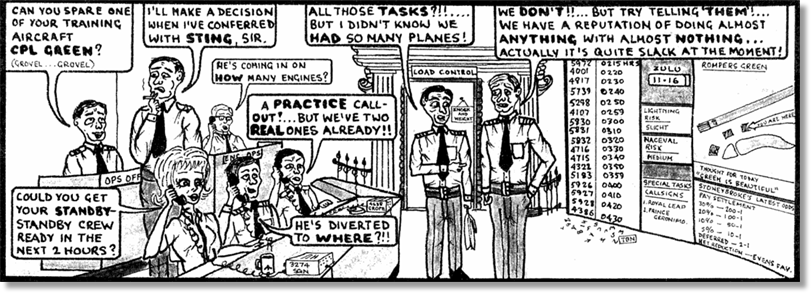

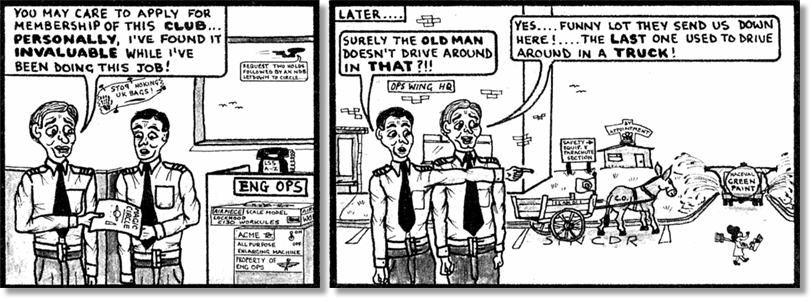

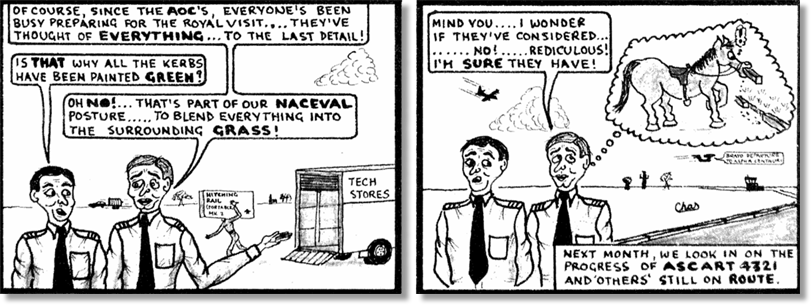

"Memories of the Whispering Giant" the best place to see them was RAF Lyneham (2 tours there Jan 66 to Dec 67) Station Air Movements. Was on Loading team on the pan and then ( Dec 70 to Dec 73 ) when I was married and in Load Control doing Britannia trim sheets.

Chas 43rd

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

"Memories of the Whispering Giant" the best place to see them was RAF Lyneham (2 tours there Jan 66 to Dec 67) Station Air Movements. Was on Loading team on the pan and then ( Dec 70 to Dec 73 ) when I was married and in Load Control doing Britannia trim sheets.

Chas 43rd

From: John Bell, Desborough, Northants

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

So many memories! Where to start?

The big one I suppose would be the Zambian Oil Lift. Day after day those of us at Nairobi loaded groups of 50 gallon drums onto plywood floor protection boards and tied them down with a necklace of chains. We developed the knack of rolling the full drums into place and then lifting them onto their ends with a ‘Snatch’ movement. No aids to do this. More than a few guys forgot to bend their knees and picked up problems with their backs that still linger around today. Some teams found it easier to load through the passenger door with a small fork lift truck. Of the hundreds of occasions we put the forks to the door I believe there were no accidents. I am sure someone will correct me if there were.

On my next detachment at the Lusaka end of the airlift the job was much easier, tipping the drums onto their sides and rolling them onto the fork tines, with backloads of empty drums. The climate and nature of the task meant that we normally worked in shorts and gloves; no shirts. (No aircrew overalls in those days). On one occasion the full team were working on a Brit when a visiting Air Officer came to observe. He asked who was in charge. Our young topless and oil smeared Flying Officer Team Leader identified himself. He was invited to leave the aircraft where he was on the receiving end of a one way chat. He returned onto the Brit a few minutes later, complete with shirt and rank braid. That same Air Officer was late for his flight back to Nairobi. The steps had been pulled away and the chocks removed. The captain would not allow us to put the steps back in so the Air Officer stood next to the marshaller, put his hand on his hips and waited until the captain powered down and opened the passenger door for us to put the steps back in.

On a task at El Adem, halfway through unloading a Brit, a long box was pushed through the freight door until only one third remained in the aircraft. To prevent it tipping I was told to sit on while the team went to fetch a truck to pick it up. The local SAMO came aboard and asked me where the rest of the team were. As I replied he became quite angry and told me to stand up when I spoke to him. I tried to explain what would happen if I did but he became more angry and louder. So I stood up and the box upended and slid out the door onto the ground outside. He charged off and no more was heard about it. The box and contents were, fortunately, undamaged.

Happy days!

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

So many memories! Where to start?

The big one I suppose would be the Zambian Oil Lift. Day after day those of us at Nairobi loaded groups of 50 gallon drums onto plywood floor protection boards and tied them down with a necklace of chains. We developed the knack of rolling the full drums into place and then lifting them onto their ends with a ‘Snatch’ movement. No aids to do this. More than a few guys forgot to bend their knees and picked up problems with their backs that still linger around today. Some teams found it easier to load through the passenger door with a small fork lift truck. Of the hundreds of occasions we put the forks to the door I believe there were no accidents. I am sure someone will correct me if there were.

On my next detachment at the Lusaka end of the airlift the job was much easier, tipping the drums onto their sides and rolling them onto the fork tines, with backloads of empty drums. The climate and nature of the task meant that we normally worked in shorts and gloves; no shirts. (No aircrew overalls in those days). On one occasion the full team were working on a Brit when a visiting Air Officer came to observe. He asked who was in charge. Our young topless and oil smeared Flying Officer Team Leader identified himself. He was invited to leave the aircraft where he was on the receiving end of a one way chat. He returned onto the Brit a few minutes later, complete with shirt and rank braid. That same Air Officer was late for his flight back to Nairobi. The steps had been pulled away and the chocks removed. The captain would not allow us to put the steps back in so the Air Officer stood next to the marshaller, put his hand on his hips and waited until the captain powered down and opened the passenger door for us to put the steps back in.

On a task at El Adem, halfway through unloading a Brit, a long box was pushed through the freight door until only one third remained in the aircraft. To prevent it tipping I was told to sit on while the team went to fetch a truck to pick it up. The local SAMO came aboard and asked me where the rest of the team were. As I replied he became quite angry and told me to stand up when I spoke to him. I tried to explain what would happen if I did but he became more angry and louder. So I stood up and the box upended and slid out the door onto the ground outside. He charged off and no more was heard about it. The box and contents were, fortunately, undamaged.

Happy days!

From: Nigel Moore, Devauden, Monmouthshire

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Dear Tony,

Happy New year! The pub is still shut, the Gauls are restless and the coal mine is now flooded, but life in Wales continues.

I attach a photo of a Brit at Kathmandu airport taken during the Gurkha Airlift between Hong Kong and Nepal when we were stationed at Kai Tak - I believe it was taken by Brian Hunt who gave me a copy.

Kind regards,

Nigel

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Dear Tony,

Happy New year! The pub is still shut, the Gauls are restless and the coal mine is now flooded, but life in Wales continues.

I attach a photo of a Brit at Kathmandu airport taken during the Gurkha Airlift between Hong Kong and Nepal when we were stationed at Kai Tak - I believe it was taken by Brian Hunt who gave me a copy.

Kind regards,

Nigel

From: Bernie Hurdsfield, Corby, Northants

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hello Tony,

My first memories of the Britannia were on my Air Movements course at Abingdon, loading and unloading the mock-up. We also spent time at Lyneham working with real loads under close supervision.

Having obtained my Q-EQ-AM qualification, I was posted to Air Movements at RAF Labuan in Borneo. This involved initially flying from London to Paya Lebar, Singapore, by a British Eagle Britannia, via Abadan (Iran) and Colombo (Ceylon), a distance of some 7,150 miles. This trip took about 30 hours in back in 1966. My tourex return a year later was again in a British Eagle Britannia, via Singapore, Bombay and Istanbul to London.

My next time working with the Britannia, was during my tour on Air Movements, Kai Tak, 1971 - 1973. The first direct air trooping of Gurkha's from Hong Kong to Kathmandu, Nepal took place during this period. This task involved working with UKMAMS, including yourself if my memory serves me right. I attach a photo of a first day cover to comemmerate it.

Best regards,

Bernie

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hello Tony,

My first memories of the Britannia were on my Air Movements course at Abingdon, loading and unloading the mock-up. We also spent time at Lyneham working with real loads under close supervision.

Having obtained my Q-EQ-AM qualification, I was posted to Air Movements at RAF Labuan in Borneo. This involved initially flying from London to Paya Lebar, Singapore, by a British Eagle Britannia, via Abadan (Iran) and Colombo (Ceylon), a distance of some 7,150 miles. This trip took about 30 hours in back in 1966. My tourex return a year later was again in a British Eagle Britannia, via Singapore, Bombay and Istanbul to London.

My next time working with the Britannia, was during my tour on Air Movements, Kai Tak, 1971 - 1973. The first direct air trooping of Gurkha's from Hong Kong to Kathmandu, Nepal took place during this period. This task involved working with UKMAMS, including yourself if my memory serves me right. I attach a photo of a first day cover to comemmerate it.

Best regards,

Bernie

From: Mike Lefebvre, Burton, NB

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

While employed at 2AMU Trenton, my first Britannia arrival, I was driving the stair truck. Of course I went to our usual door, the one we normally used when handling the Yukon. It took me a while to understand the RAF crew hand signals, never seen those before. They were telling me to go to the starboard door, we normally used the one on the port side. Learn something new every day.

Every Sunday morning we loaded the Yukon scheduled Flight 308 for Cyprus - doubled over in the front belly hold, bulk full of ration boxes. We put plywood on the rollers and made a human chain, cramped on our knees, sweating and with some of our manpower a little hung over from the previous evening. We never finished the job without an evacuation due to either Ray or Was letting one go. Many 2 AMU past members know these infamous two.

Vern Mike

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

While employed at 2AMU Trenton, my first Britannia arrival, I was driving the stair truck. Of course I went to our usual door, the one we normally used when handling the Yukon. It took me a while to understand the RAF crew hand signals, never seen those before. They were telling me to go to the starboard door, we normally used the one on the port side. Learn something new every day.

Every Sunday morning we loaded the Yukon scheduled Flight 308 for Cyprus - doubled over in the front belly hold, bulk full of ration boxes. We put plywood on the rollers and made a human chain, cramped on our knees, sweating and with some of our manpower a little hung over from the previous evening. We never finished the job without an evacuation due to either Ray or Was letting one go. Many 2 AMU past members know these infamous two.

Vern Mike

From: Tony Street, Buffalo, NY

Subject: The Canadair CC-160 Yukon

During the 1960's, about fifty percent of flights between Canada, Marville and Lahr were cargo flights. A load of servicemen with their dependants were rotated on day one, followed by their belongings and cargo on day two. This went on for a few years. I was a Yukon loadie for a few years (437 Squsdron, CYTR).

412 Squadron in Ottawa had a VIP Yukon with a very plush interior; even had it's own chef!

Cheers,

Tony

Subject: The Canadair CC-160 Yukon

During the 1960's, about fifty percent of flights between Canada, Marville and Lahr were cargo flights. A load of servicemen with their dependants were rotated on day one, followed by their belongings and cargo on day two. This went on for a few years. I was a Yukon loadie for a few years (437 Squsdron, CYTR).

412 Squadron in Ottawa had a VIP Yukon with a very plush interior; even had it's own chef!

Cheers,

Tony

From: Peter Thompson, Sunderland, Tyne and Wear

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

What I mostly remember of the Britannia were the small and cramped belly holds, the unbelievably heavy and awkward TPU's (Tech Packups), but most of all leaving tufts of hair attached to the rivets along the roof of the hold. No wonder there were a lot of premature baldies in the trade! Apart from that I really liked the old girl.

Peter (Hammy) Thompson.

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

What I mostly remember of the Britannia were the small and cramped belly holds, the unbelievably heavy and awkward TPU's (Tech Packups), but most of all leaving tufts of hair attached to the rivets along the roof of the hold. No wonder there were a lot of premature baldies in the trade! Apart from that I really liked the old girl.

Peter (Hammy) Thompson.

From: Howard Firth, Cranwell Village, Lincs

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

A Happy New Year to you and all members of UKMAMS OBA.

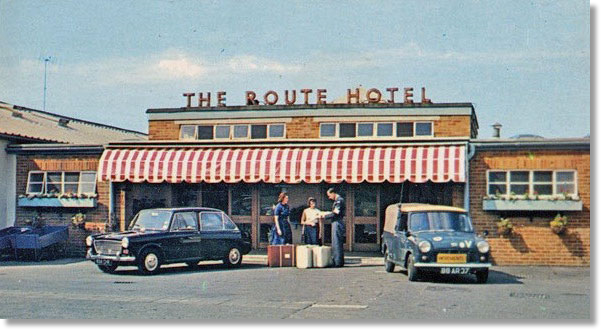

My initial introduction to working with this fine aircraft was on my first posting as a Mover in 1970 to RAF Lyneham where, as an SAC, I worked in the Route Hotel with Eddie Gordon.

Not long after my arrival the fleet was reassigned to Brize where I worked on A Shift Pax with Sgt Bob Campbell. Then followed tours in Gan, Luqa, Akrotiri and Wildenrath, although by then I think the aircraft had been retired.

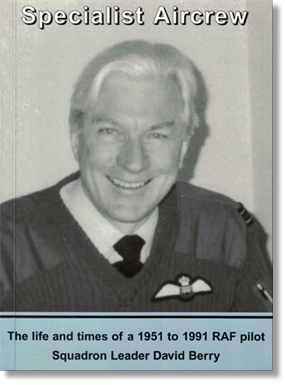

Prompted by your request I dug out a couple of books on the subject both written by Sqn Ldr Dave Berry, father of SAC Mover Raz Berry. The first book is entitled, “The Whispering Giant in Uniform” and the second, “Tales from the Crew Room”.

A Happy New Year to you and all members of UKMAMS OBA.

My initial introduction to working with this fine aircraft was on my first posting as a Mover in 1970 to RAF Lyneham where, as an SAC, I worked in the Route Hotel with Eddie Gordon.

Not long after my arrival the fleet was reassigned to Brize where I worked on A Shift Pax with Sgt Bob Campbell. Then followed tours in Gan, Luqa, Akrotiri and Wildenrath, although by then I think the aircraft had been retired.

Prompted by your request I dug out a couple of books on the subject both written by Sqn Ldr Dave Berry, father of SAC Mover Raz Berry. The first book is entitled, “The Whispering Giant in Uniform” and the second, “Tales from the Crew Room”.

They are highly informative and humourous books and I would recommend them to both the young and old amongst us. Full of nostalgia, especially the chapter on the Changi Slip.

I look forward to reading the Movers stories of the “Brit” in the next edition. Off to South Africa tomorrow for 8 weeks to play golf and escape the UK weather.

Regards

“H” Firth

I look forward to reading the Movers stories of the “Brit” in the next edition. Off to South Africa tomorrow for 8 weeks to play golf and escape the UK weather.

Regards

“H” Firth

Further to "H" Firth's comments regarding the books written by Sqn Ldr Dave Berry about the Britannia - back in October 2000, David sent me a copy of his latest book at that time, "Specialist Aircrew". I've transcribed an excerpt from Chapter 20:

The start of 1970 found me cheerfully back in the left seat of a Britannia, at Lyneham, undergoing what was called ‘Retread Training’. It was to be hoped that by using this term, borrowed from the car tyre trade, was not a reflection on our perceived subsequent reliability.

Twenty-two hours of flying, which included a route trip to Malta and return, saw me considered ‘retreaded’ to sufficient quality to return to 99 Squadron.

My first trip? Well, not a full Changi Slip, but halfway there and return – and I was pleased to be back, doing just that.

It might be considered that my recent Britannia experience was pretty humble… but on my next trip I had royalty on board. We were due to fly an aircraft out of Cyprus to Lyneham. When reporting to Akrotiri Ops, the word was:

Twenty-two hours of flying, which included a route trip to Malta and return, saw me considered ‘retreaded’ to sufficient quality to return to 99 Squadron.

My first trip? Well, not a full Changi Slip, but halfway there and return – and I was pleased to be back, doing just that.

It might be considered that my recent Britannia experience was pretty humble… but on my next trip I had royalty on board. We were due to fly an aircraft out of Cyprus to Lyneham. When reporting to Akrotiri Ops, the word was:

“Your passengers are all Army – they’ve been on exercise here. Perhaps you should know that the Major in charge is HRH The Duke of Kent, but he wants to be treated as a normal passenger.

Well, that made life easy.

Off we set from Akrotiri, westwards over the various Greek islands; Rodos, Araxos, Milos, turning north west at Caraffa on the toe of Italy to fly up the west coast, then heading for Nice.

As was routine, we were listening to the hourly broadcasts of the latest weather at the UK airfields. Lyneham was fine but when we were passed the latest forecast, things did not look good; early morning fog was due to creep over the Lyneham Bank and sit over the airfield. We started making plans for a possible diversion airfield. At this stage, I decided that HRH could not be treated ‘as a normal passenger’. Hat on, I retired to the passenger cabin.

Well, that made life easy.

Off we set from Akrotiri, westwards over the various Greek islands; Rodos, Araxos, Milos, turning north west at Caraffa on the toe of Italy to fly up the west coast, then heading for Nice.

As was routine, we were listening to the hourly broadcasts of the latest weather at the UK airfields. Lyneham was fine but when we were passed the latest forecast, things did not look good; early morning fog was due to creep over the Lyneham Bank and sit over the airfield. We started making plans for a possible diversion airfield. At this stage, I decided that HRH could not be treated ‘as a normal passenger’. Hat on, I retired to the passenger cabin.

“It does look, Sir, as if we might not be able to land at Lyneham. Manchester looks like a strong bet. Is there anyone you would like us to inform?”

It seemed not, he was quite happy to continue ‘as a normal passenger’. As we approached the English Channel, the Met Men continued with their threat of fog at any moment, although the current visibility was good. We passed over London, turning west for Wiltshire and reducing height. Swindon came into sight and there, eight miles to the west, was the Lyneham runway, loud and clear. This was the way of things, more often than not.

As we settled on the final approach, I happened to glance over my shoulder and there was His Royal Highness, standing in the doorway, with a headset on, listening to all that was going on. The air quartermaster had thought it would be a good idea ‘to keep him in the picture’. I pointed out to this young man, later, that it would have also been a good idea to let us know what was happening. There could have been a lot of inappropriate flight deck banter – not an uncommon practice – perhaps on the topic of the reuniting of our ‘normal passenger’ and Her Royal Highness. Such reunion matters always weighed heavily on our minds for those last few hours before homecoming!

I will allude to the ‘new mix’ crew-wise, with which one started each trip. This could produce interest, amusement, tension or irritation. It would put a newcomer up to test as he demonstrated his abilities, both professional and social, to a critical audience – and adjusted himself to his new compatriots. For a trip to Cyprus, this April, my navigator was a recently arrived flight commander. These people had a double burden – settling in as a proficient crew member and establishing themselves in their executive role. My Squadron Leader navigator was trying very hard in all directions.

We had hired Akrotiri’s recreational mini-bus for a tour of the island. Lunch at the Paphos harbour-side, with its pelican, was a starting point. Moving on, we spotted a motor club hill climb and decided to view it from the terrace of a convenient tavern. The navigator had done a tour in Cyprus and there had been several occasions already where, for our benefit, he had aired his local knowledge. Now the recommendation was:

“Try Ouzo – it’s the Cyprus version of Pernod – yeah, goes cloudy when you add water… I’ll get them!”

The wizened, clad in black, landlady approaches.

“Six Ouzos please.”

It seemed not, he was quite happy to continue ‘as a normal passenger’. As we approached the English Channel, the Met Men continued with their threat of fog at any moment, although the current visibility was good. We passed over London, turning west for Wiltshire and reducing height. Swindon came into sight and there, eight miles to the west, was the Lyneham runway, loud and clear. This was the way of things, more often than not.

As we settled on the final approach, I happened to glance over my shoulder and there was His Royal Highness, standing in the doorway, with a headset on, listening to all that was going on. The air quartermaster had thought it would be a good idea ‘to keep him in the picture’. I pointed out to this young man, later, that it would have also been a good idea to let us know what was happening. There could have been a lot of inappropriate flight deck banter – not an uncommon practice – perhaps on the topic of the reuniting of our ‘normal passenger’ and Her Royal Highness. Such reunion matters always weighed heavily on our minds for those last few hours before homecoming!

I will allude to the ‘new mix’ crew-wise, with which one started each trip. This could produce interest, amusement, tension or irritation. It would put a newcomer up to test as he demonstrated his abilities, both professional and social, to a critical audience – and adjusted himself to his new compatriots. For a trip to Cyprus, this April, my navigator was a recently arrived flight commander. These people had a double burden – settling in as a proficient crew member and establishing themselves in their executive role. My Squadron Leader navigator was trying very hard in all directions.

We had hired Akrotiri’s recreational mini-bus for a tour of the island. Lunch at the Paphos harbour-side, with its pelican, was a starting point. Moving on, we spotted a motor club hill climb and decided to view it from the terrace of a convenient tavern. The navigator had done a tour in Cyprus and there had been several occasions already where, for our benefit, he had aired his local knowledge. Now the recommendation was:

“Try Ouzo – it’s the Cyprus version of Pernod – yeah, goes cloudy when you add water… I’ll get them!”

The wizened, clad in black, landlady approaches.

“Six Ouzos please.”

There is a look of disbelief on the old woman’s face, “Seecks?!!”

Navigator waves six fingers in the air and adopts the traditional course of action when a foreigner doesn’t understand – say the same thing again – but louder, “SIX OUZOS, PLEASE.”

The landlady shrugs her shoulders and shuffles off. We settle on the terrace chairs. The old lady reappears with a tray holding six glasses, a jug of water and six BOTTLES of Ouzo. With a fixed grin, the navigator had to put on the appearance of ‘that is what he had meant’. It now fell on us to back that by getting on and consuming same!

It has to be admitted that the bottles were only 35cl size but the contents were sufficient to upset the judgement of my crew; the engineer persuaded a local to lend him his rather decrepit looking horse to ride around the village square; the co-pilot fell in love with a Cypriot lady almost as old as the provider of our libation and our lady air quartermaster managed to lock herself in the toilet. I’ve never fancied that aniseed flavoured drink since.

It did seem we spent half our lives in Cyprus. If you were en route for Bahrain, Gan, Singapore, Hong Kong, an eastbound global trip, Nairobi, Australia – in fact all points east, then in this era, the first stop was Akrotiri. Cyprus itself generated flights with the large military presence on the island requiring support – and it was used as an exercise area. So, a trip to Akrotiri was a very familiar one and one that could be flown in an automatic way. From Lyneham, the routing over London, down over France, the west coast of Italy and then over the Greek islands was always the same. Leaving Athens control, the handover was to Nicosia Centre.

“Nicosia Centre, this is Ascot 6543 on handover from Athens at flight level 230.”

“Ascot 6543 Nicosia centre, roger. You are clear to descend to flight level 130.”

Nicosia, 6543, leaving 230 for 130.”

The height lock on the autopilot disengaged and the pitch control switch lowered the nose slightly. The speed increased from 240 knots, cruising, to the maximum permitted of 258 knots. At that speed the airspeed lock engaged. The outboard throttles moved to the backstop, followed by the inboards. The needle on the altimeter wound rapidly anti-clockwise as the height decreased.

“Nicosia, Ascot 6543 passing 150 for 130.”

Navigator waves six fingers in the air and adopts the traditional course of action when a foreigner doesn’t understand – say the same thing again – but louder, “SIX OUZOS, PLEASE.”

The landlady shrugs her shoulders and shuffles off. We settle on the terrace chairs. The old lady reappears with a tray holding six glasses, a jug of water and six BOTTLES of Ouzo. With a fixed grin, the navigator had to put on the appearance of ‘that is what he had meant’. It now fell on us to back that by getting on and consuming same!

It has to be admitted that the bottles were only 35cl size but the contents were sufficient to upset the judgement of my crew; the engineer persuaded a local to lend him his rather decrepit looking horse to ride around the village square; the co-pilot fell in love with a Cypriot lady almost as old as the provider of our libation and our lady air quartermaster managed to lock herself in the toilet. I’ve never fancied that aniseed flavoured drink since.

It did seem we spent half our lives in Cyprus. If you were en route for Bahrain, Gan, Singapore, Hong Kong, an eastbound global trip, Nairobi, Australia – in fact all points east, then in this era, the first stop was Akrotiri. Cyprus itself generated flights with the large military presence on the island requiring support – and it was used as an exercise area. So, a trip to Akrotiri was a very familiar one and one that could be flown in an automatic way. From Lyneham, the routing over London, down over France, the west coast of Italy and then over the Greek islands was always the same. Leaving Athens control, the handover was to Nicosia Centre.

“Nicosia Centre, this is Ascot 6543 on handover from Athens at flight level 230.”

“Ascot 6543 Nicosia centre, roger. You are clear to descend to flight level 130.”

Nicosia, 6543, leaving 230 for 130.”

The height lock on the autopilot disengaged and the pitch control switch lowered the nose slightly. The speed increased from 240 knots, cruising, to the maximum permitted of 258 knots. At that speed the airspeed lock engaged. The outboard throttles moved to the backstop, followed by the inboards. The needle on the altimeter wound rapidly anti-clockwise as the height decreased.

“Nicosia, Ascot 6543 passing 150 for 130.”

“Roger 6543, contact Akrotiri approach on two three fife decimal three. Good day, Sir.”

“6543, Good day.”

The frequency dial on the UHF set clicked around to the pre-selected frequency for approach. The UHF buttons on the communications boxes at crew member’s stations popped in.

The autopilot airspeed lock went in and the pitch control switch flicked back in blips to level the aircraft. On reaching flight level 130, the height lock came out and, as the speed dropped, the throttles moved forward to give sufficient power to maintain 200 knots.

“Akrotiri approach, this is Ascot 6543, flight level 130. Request further descent.”

“Ascot 6543, Akrotiri, you’re loud and clear, continue descent to two thousand feet. QFE one zero one zero.”

“Roger, 6543 re-cleared to two thousand, one zero one zero is set, leaving 130.”

The height knob clicks in, twists through 180º and comes out to engage the airspeed lock. In pairs the throttles come back to ‘Flight Idle’.

On the Tacan, the range from Akrotiri clicks down. It is a mid-summer night, clear but with the lights on the ground shimmering in the remains of the daytime heat. From a range of ten miles it is the lights of Akrotiri that are flickering in the distance.

“Akrotiri approach, 6543, airfield in sight, request join downwind for a visual circuit.”

“6543, clear join, call tower on two three two decimal one.”

The aircraft is now passing 2000 feet and once again the airspeed/height lock clicks in and the pitch control blips back to slow the rate of descent. The airspeed is allowed to decay.

“Akrotiri tower, Ascot 6543 is downwind to land.”

“Roger 6543, call turning finals, the wind two niner zero at fife knots.”

“6543, Good day.”

The frequency dial on the UHF set clicked around to the pre-selected frequency for approach. The UHF buttons on the communications boxes at crew member’s stations popped in.

The autopilot airspeed lock went in and the pitch control switch flicked back in blips to level the aircraft. On reaching flight level 130, the height lock came out and, as the speed dropped, the throttles moved forward to give sufficient power to maintain 200 knots.

“Akrotiri approach, this is Ascot 6543, flight level 130. Request further descent.”

“Ascot 6543, Akrotiri, you’re loud and clear, continue descent to two thousand feet. QFE one zero one zero.”

“Roger, 6543 re-cleared to two thousand, one zero one zero is set, leaving 130.”

The height knob clicks in, twists through 180º and comes out to engage the airspeed lock. In pairs the throttles come back to ‘Flight Idle’.

On the Tacan, the range from Akrotiri clicks down. It is a mid-summer night, clear but with the lights on the ground shimmering in the remains of the daytime heat. From a range of ten miles it is the lights of Akrotiri that are flickering in the distance.

“Akrotiri approach, 6543, airfield in sight, request join downwind for a visual circuit.”

“6543, clear join, call tower on two three two decimal one.”

The aircraft is now passing 2000 feet and once again the airspeed/height lock clicks in and the pitch control blips back to slow the rate of descent. The airspeed is allowed to decay.

“Akrotiri tower, Ascot 6543 is downwind to land.”

“Roger 6543, call turning finals, the wind two niner zero at fife knots.”

Time for the autopilot to disengage. A perfect night, made moreso with a gentle wind right down the runway. Approaching 1000 feet, there is a whine as the flaps run to the 15º position. The throttles advance to give 250lbs of torque. The speed stabilises at 160 knots as the aircraft gently banks to the left to take up the downwind heading of 110º.

There is an increase in the roar from the airflow as the undercarriage starts to lower; two powerful clunks and one lesser one signal that the main and nose wheels are down and locked. The three undercarriage indicator lights have gone from off to shine red then green to indicate this. A little more power is needed to maintain 150 knots. Opposite to the upwind of the runway the aircraft banks and the nose drops. The throttles come back to give 200lbs of torque. There is that whine once more as the flaps move to the 30º position. The speed falls off to 140 knots.

“Tower, 6543 is turning finals with three greens to land.”

“6543 is clear to land, wind still two niner zero at fife knots.”

“6543.”

The turn continues; bank is adjusted as the runway comes into sight ahead. Two beams of light appear below the wings and rotate upwards to shine ahead; the landing lamp switch had moved to the ‘on’ position. The power setting is spot on; the angle of approach indicator lights on either side of the runway show green/red – also spot on. At 400 feet the speed is 130 knots; the whine again as the flaps lower to 45º. The nose has to be lowered to prevent the speed falling too low; it settles at 120 knots, 5 knots above the threshold speed – once again, spot on. The trim wheels are rotating forward to adjust for the lowering of full flaps.

The approach lights are now glaring up on the underside of the aircraft and the red lights marking the runway threshold are crossed. The ground looms up but the control column moves back to hold the aircraft level just above the ground; the throttles retract to the flight idle position. As the speed falls off, the control column comes back and back and then the main wheels kiss the runway surface. (This didn’t always happen with a Britannia landing!)

The noise level increases with the rumble of the tyres; the control column moves gently forward to place the nose wheel on the ground. There is the sound of a hammer blow – that is ‘Superfine’ being engaged. This reduces the angle of the propeller blades, below that used in flight, to allow the propellers to run fast enough on the ground to keep the alternators on line.

There is an increase in the roar from the airflow as the undercarriage starts to lower; two powerful clunks and one lesser one signal that the main and nose wheels are down and locked. The three undercarriage indicator lights have gone from off to shine red then green to indicate this. A little more power is needed to maintain 150 knots. Opposite to the upwind of the runway the aircraft banks and the nose drops. The throttles come back to give 200lbs of torque. There is that whine once more as the flaps move to the 30º position. The speed falls off to 140 knots.

“Tower, 6543 is turning finals with three greens to land.”

“6543 is clear to land, wind still two niner zero at fife knots.”

“6543.”

The turn continues; bank is adjusted as the runway comes into sight ahead. Two beams of light appear below the wings and rotate upwards to shine ahead; the landing lamp switch had moved to the ‘on’ position. The power setting is spot on; the angle of approach indicator lights on either side of the runway show green/red – also spot on. At 400 feet the speed is 130 knots; the whine again as the flaps lower to 45º. The nose has to be lowered to prevent the speed falling too low; it settles at 120 knots, 5 knots above the threshold speed – once again, spot on. The trim wheels are rotating forward to adjust for the lowering of full flaps.

The approach lights are now glaring up on the underside of the aircraft and the red lights marking the runway threshold are crossed. The ground looms up but the control column moves back to hold the aircraft level just above the ground; the throttles retract to the flight idle position. As the speed falls off, the control column comes back and back and then the main wheels kiss the runway surface. (This didn’t always happen with a Britannia landing!)

The noise level increases with the rumble of the tyres; the control column moves gently forward to place the nose wheel on the ground. There is the sound of a hammer blow – that is ‘Superfine’ being engaged. This reduces the angle of the propeller blades, below that used in flight, to allow the propellers to run fast enough on the ground to keep the alternators on line.

The foot brakes on the rudder pedals depress and the slight jerk on the aircraft confirms that the brakes are working. With that, the throttles move forward to the position they were in for touch-down. This will now give ‘ground-idle’ power from the engines.

A lever to the right of the throttles moves rearwards and five red lights illuminate on the centre of the instrument panel coaming – the controls are locked. Once more, there is the distinctive sound of the flap motors as the flaps are raised, fully up.

The aircraft trundles up to the end of the runway and turns left. The intensity of the landing lights is reduced as the landing light switch moves to the taxy lamp position. The taxiway curves round to the left and then there is a sharp right turn into the parking area.

Ahead, the illumination wands of the ground marshaller beckon. The taxy lamp switch goes top off. As the aircraft reached the required spot the marshaller crosses his wands over his head. The brakes go fully on and the parking brake lever clicks on its ratchet.

Switches now move rapidly; there is a clunk as the superfine switch moves; the four high pressure switches go to off; the engine noise immediately dies. As the rpm falls away, more switches move to close the low-pressure fuel and the oil cocks. Brakes to the propellers go on and as they come to a standstill, the underside flashing red light extinguishes indicating to the ground crew that it is safe to approach the aircraft. The noise outside is the ground power unit starting up. A green light on the electrical panel indicates that it is ready to supply current to the aircraft.

The Movements Staff, who will be attending to the load, push a set of steps to the rear door of the aircraft. Tradition dictates that they do not mount these yet. They wait for the air quartermaster to open the door from inside the aircraft and descend the steps to hand over the necessary paperwork and brief the Movements Officer on the requirements.

With the engines stopped, aircraft exterior lights extinguished and steps in position, the scene is much calmer now, although the grinding of the ground power unit does not allow complete peace.

The Movers wait for the door to open, but it remains shut. They wait patiently. Minutes tick by – something is clearly wrong. The officer leads the way up the steps and the door is opened from the outside. The ground team step into the aircraft… no air quartermaster… the passenger/freight cabin is deserted.

“He must be on the flight deck,” volunteers the officer.

A lever to the right of the throttles moves rearwards and five red lights illuminate on the centre of the instrument panel coaming – the controls are locked. Once more, there is the distinctive sound of the flap motors as the flaps are raised, fully up.

The aircraft trundles up to the end of the runway and turns left. The intensity of the landing lights is reduced as the landing light switch moves to the taxy lamp position. The taxiway curves round to the left and then there is a sharp right turn into the parking area.

Ahead, the illumination wands of the ground marshaller beckon. The taxy lamp switch goes top off. As the aircraft reached the required spot the marshaller crosses his wands over his head. The brakes go fully on and the parking brake lever clicks on its ratchet.

Switches now move rapidly; there is a clunk as the superfine switch moves; the four high pressure switches go to off; the engine noise immediately dies. As the rpm falls away, more switches move to close the low-pressure fuel and the oil cocks. Brakes to the propellers go on and as they come to a standstill, the underside flashing red light extinguishes indicating to the ground crew that it is safe to approach the aircraft. The noise outside is the ground power unit starting up. A green light on the electrical panel indicates that it is ready to supply current to the aircraft.

The Movements Staff, who will be attending to the load, push a set of steps to the rear door of the aircraft. Tradition dictates that they do not mount these yet. They wait for the air quartermaster to open the door from inside the aircraft and descend the steps to hand over the necessary paperwork and brief the Movements Officer on the requirements.

With the engines stopped, aircraft exterior lights extinguished and steps in position, the scene is much calmer now, although the grinding of the ground power unit does not allow complete peace.

The Movers wait for the door to open, but it remains shut. They wait patiently. Minutes tick by – something is clearly wrong. The officer leads the way up the steps and the door is opened from the outside. The ground team step into the aircraft… no air quartermaster… the passenger/freight cabin is deserted.

“He must be on the flight deck,” volunteers the officer.

He moves up the cabin, past the lashed-down freight and opens the flight deck door. No one… all five crew seats are empty. There is a double click to his right… he looks down… it’s the electrical panel and he sees two switches rotating, unaided, from the ‘Flight’ position to ‘Ground’.

It is the ‘Marie Celeste’ revisited – the aircraft has flown to Akrotiri so many times that, on this occasion, it has got there all by itself!

The Movements Officer rushes down the cabin and steps and grabs the radio in his Land Rover. He struggles to control his voice as he calls his superior, the Senior Air Movements Officer.

“6543 - just landed – taxied in – but there’s no one on board!”

“Well, there wouldn’t be, the crew are up here in the Transit Lounge Bar having their wind-down beers…"

It is the ‘Marie Celeste’ revisited – the aircraft has flown to Akrotiri so many times that, on this occasion, it has got there all by itself!

The Movements Officer rushes down the cabin and steps and grabs the radio in his Land Rover. He struggles to control his voice as he calls his superior, the Senior Air Movements Officer.

“6543 - just landed – taxied in – but there’s no one on board!”

“Well, there wouldn’t be, the crew are up here in the Transit Lounge Bar having their wind-down beers…"

From: Jim Nadin, Lincoln

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

Happy New Year to you also.

My one and only memory of the Whispering Giant was at Coltishall in 1968. As a very wet behind the ears LAC whose first ever flight was an air experience sortie in a Hastings from Scampton, the Britannia was something completely different. As I recall, she had dropped into Coltishall to pick up a Lightning fly away pack for a forthcoming Cyprus detachment and I was nominated to assist in the ‘humping and dumping’ of the crates.

The loadmaster invited me on board and I was simply awe struck by the cavernous interior. Even more so when he told me that 50 or more stretchers, medical staff and life saving equipment could be carried. I was impressed but sadly never got to fly in one although some I have spoken to were less enthusiastic about their passenger experiences.

Best wishes

Jim

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

Happy New Year to you also.

My one and only memory of the Whispering Giant was at Coltishall in 1968. As a very wet behind the ears LAC whose first ever flight was an air experience sortie in a Hastings from Scampton, the Britannia was something completely different. As I recall, she had dropped into Coltishall to pick up a Lightning fly away pack for a forthcoming Cyprus detachment and I was nominated to assist in the ‘humping and dumping’ of the crates.

The loadmaster invited me on board and I was simply awe struck by the cavernous interior. Even more so when he told me that 50 or more stretchers, medical staff and life saving equipment could be carried. I was impressed but sadly never got to fly in one although some I have spoken to were less enthusiastic about their passenger experiences.

Best wishes

Jim

From: John Holloway, Shrewsbury, Salop

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

The only Britannia I've seen in RAF colours is the one at the RAF Museum at Cosford; it arrived back in the 80's and was in BOAC livery, G-AOVF. It was eventually repainted in false RAF colours as "Schedar" XM497.

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

The only Britannia I've seen in RAF colours is the one at the RAF Museum at Cosford; it arrived back in the 80's and was in BOAC livery, G-AOVF. It was eventually repainted in false RAF colours as "Schedar" XM497.

In October 1956, I was posted to Khormaksar from HQBF when we invaded Suez, so all scheduled flights went out of the window. All sorts of aircraft were arriving and on one occasion Air Trafic Control phoned us informing us that we had two Britannia's arriving and, as usual, informed us of any officers on board. One of them had a forward party of The King's Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI) my home county regiment, and the officer i/c was Lt John McKiernan, an old school pal!

So, of course I made a point of going out with the meeting party when the kite arrived and parked and stood at the bottom of the steps as the passengers disembarked. The Brits were in BOAC livery as the MoD were commandeering aircraft just like many years later with the Falklands and the ships that were needed. Anyhow, Mac eventually appeared, came down the steps where I met him and I can't recall what was said, but he hadn't a clue where he was or where he was going which was to be next day by Valetta to Bahrain.

As I said, all sorts of aircraft were arriving, mainly Avro Yorks and Tudors carrying freight. To see a Tudor landing at night was quite a sight when the engines throttled back with the flames coming out of the exhausts and the crackle of the engines.

One night we had to unload the freight off a York and it would be in the dark as it was being refuelled and the only lights were on the ground. I had a roll of barbed wire fall against my legs and I've still got the scars to show for it!

Cheers

John

So, of course I made a point of going out with the meeting party when the kite arrived and parked and stood at the bottom of the steps as the passengers disembarked. The Brits were in BOAC livery as the MoD were commandeering aircraft just like many years later with the Falklands and the ships that were needed. Anyhow, Mac eventually appeared, came down the steps where I met him and I can't recall what was said, but he hadn't a clue where he was or where he was going which was to be next day by Valetta to Bahrain.

As I said, all sorts of aircraft were arriving, mainly Avro Yorks and Tudors carrying freight. To see a Tudor landing at night was quite a sight when the engines throttled back with the flames coming out of the exhausts and the crackle of the engines.

One night we had to unload the freight off a York and it would be in the dark as it was being refuelled and the only lights were on the ground. I had a roll of barbed wire fall against my legs and I've still got the scars to show for it!

Cheers

John

From: Howard Farrow, Swansea, Glamorgan

Subject: Memories of the Britannia

As a Brize Mover in 1972, I was posted to RAF Masirah for a stint in the sun. My flight from Brize was to be on a 99 Sqn Britannia. As I had been working on C shift Pax, the lads had managed to allocate me a main door triple to myself - Movers perk!

On saying cheerio to the lads, the door was closed and I settled back in comfort, the engines wound up and we abruptly left the bay only for me to find myself looking up at the cabin ceiling; the triple had not been fitted properly and was lying across the legs of three army lads in the row behind! The aircraft stopped, steps went in and two red-faced Role Equippers came on to great applause!

The rest of the flight was thankfully uneventful, staging at Akrotiri before landing at Masirah where I was met by members of my new shift. One of them put his arm around my shoulder and remarked 'how white I looked' and 'that nobody had that many days to do!" That was the great Mover Dave Wall!

That was my first and last flight on a Brit!

Howard (Taff) Farrow

Subject: Memories of the Britannia

As a Brize Mover in 1972, I was posted to RAF Masirah for a stint in the sun. My flight from Brize was to be on a 99 Sqn Britannia. As I had been working on C shift Pax, the lads had managed to allocate me a main door triple to myself - Movers perk!

On saying cheerio to the lads, the door was closed and I settled back in comfort, the engines wound up and we abruptly left the bay only for me to find myself looking up at the cabin ceiling; the triple had not been fitted properly and was lying across the legs of three army lads in the row behind! The aircraft stopped, steps went in and two red-faced Role Equippers came on to great applause!

The rest of the flight was thankfully uneventful, staging at Akrotiri before landing at Masirah where I was met by members of my new shift. One of them put his arm around my shoulder and remarked 'how white I looked' and 'that nobody had that many days to do!" That was the great Mover Dave Wall!

That was my first and last flight on a Brit!

Howard (Taff) Farrow

From: David Forsyth, Le Langon

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

What have you done, Norrie?

I have included names in this Britannia story as I am sure readers, like me, enjoy Tony’s Newletters for the names which come as blasts from the past. Unfortunately, the hero of the story, Norrie, is no longer answering roll calls but I hope he would have enjoyed being reminded of this little caper- then again, maybe not?

Word that a big exercise, Bersatu Padu, was to take place in 1970 began to circulate at Marham just after the Tanker Force had featured successfully in the Daily Mail Air Race, in-flight re-fuelling a Harrier and a Canberra on their way to and from New York. Morale at Marham was sky high as it was clear that 55, 57 and 214 Squadrons’ Victors, underpowered as they were, were then the best in the world at Air to Air Refuelling and all the complex planning which went into it.

I was fresh out of Cranwell, pilot officer “commanding” (for which read: “being kept right by Flight Seargent Jack”) the ESG at Marham- an organisation heavily solicited, with its electrical engineering techie peers, to enable the Victors do what they did so well. Fly Away Packs (FAPs) for Victor detachments were large, heavy affairs amounting to several thousand lbs and several dozen different sized wooden boxes (no ISOFIX stuff then) as well as large amounts of ground support equipment. Detachment FAPs were generally managed by a corporal or a sergeant and a couple of airmen. I was keen to get an overseas trip so prevailed upon mates in the flying squadrons to persuade their bosses that such an important exercise needed the presence of a pilot officer!

The first deployment to support Lightnings transiting to Singapore was from Marham to Luqa, lasting a week or so, then moving on to Akrotiri for another week or so prior to returning to Marham, the 'Giant Norfolk Air Base' as it had been termed in a Daily Mail article about their race to New York. Flying Officer George Hutt, the officer in charge of FAPs, his team and a MAMS team loaded all the kit plus a gaggle of techies and spare aircrew on to a Britannia and off we trundled to Luqa in Malta. I had not actively participated in loading and trimming the aircraft but George had briefed me on what was where and I had all the manifests and other papers in a nav bag I had persuaded clothing stores to lend me.

Arrival early evening in Luqa, we were met by the SAMO, I think that was Brian Everett, Richard Johnson (Load Control Officer) and Norrie Radcliffe (DAMO). My offer to help with the unloading was quickly turned down by Norrie who probably did not need or deserve his team being slowed down by the likes of me. “Off you go to the Mess, your stuff will be delivered to Sunspot in the morning” was Norrie’s sound advice, and I needed no second bidding.

Word that a big exercise, Bersatu Padu, was to take place in 1970 began to circulate at Marham just after the Tanker Force had featured successfully in the Daily Mail Air Race, in-flight re-fuelling a Harrier and a Canberra on their way to and from New York. Morale at Marham was sky high as it was clear that 55, 57 and 214 Squadrons’ Victors, underpowered as they were, were then the best in the world at Air to Air Refuelling and all the complex planning which went into it.

I was fresh out of Cranwell, pilot officer “commanding” (for which read: “being kept right by Flight Seargent Jack”) the ESG at Marham- an organisation heavily solicited, with its electrical engineering techie peers, to enable the Victors do what they did so well. Fly Away Packs (FAPs) for Victor detachments were large, heavy affairs amounting to several thousand lbs and several dozen different sized wooden boxes (no ISOFIX stuff then) as well as large amounts of ground support equipment. Detachment FAPs were generally managed by a corporal or a sergeant and a couple of airmen. I was keen to get an overseas trip so prevailed upon mates in the flying squadrons to persuade their bosses that such an important exercise needed the presence of a pilot officer!

The first deployment to support Lightnings transiting to Singapore was from Marham to Luqa, lasting a week or so, then moving on to Akrotiri for another week or so prior to returning to Marham, the 'Giant Norfolk Air Base' as it had been termed in a Daily Mail article about their race to New York. Flying Officer George Hutt, the officer in charge of FAPs, his team and a MAMS team loaded all the kit plus a gaggle of techies and spare aircrew on to a Britannia and off we trundled to Luqa in Malta. I had not actively participated in loading and trimming the aircraft but George had briefed me on what was where and I had all the manifests and other papers in a nav bag I had persuaded clothing stores to lend me.

Arrival early evening in Luqa, we were met by the SAMO, I think that was Brian Everett, Richard Johnson (Load Control Officer) and Norrie Radcliffe (DAMO). My offer to help with the unloading was quickly turned down by Norrie who probably did not need or deserve his team being slowed down by the likes of me. “Off you go to the Mess, your stuff will be delivered to Sunspot in the morning” was Norrie’s sound advice, and I needed no second bidding.

The next morning, in the company of Flight Lieutenant Dave Richmond, the detachment engineering officer (who towered above my 6 ft 3in), I drove in a borrowed Landy to the block of buildings at the side of Luqa airfield called Sunspot. Our arrival coincided with a tractor pulling several low-loader trailers carrying a load of boxes from the FAP which, with the Movers, I set to install in the storage area. After an hour or so and a few more tractor deliveries, I realised we were missing several boxes adding up to a weight of about 4,500 lbs.

With Richmond in the passenger seat, where his anxiety was beginning to make his size seem even bigger, I drove round to the Air Movements Section and asked where the missing stuff could be. After several minutes of assurances that it must be here somewhere and hunting in the few places it could be, both logically and illogically, we came to the conclusion that it was not in Malta or at least not at Luqa. I remembered George Hutt telling me he had loaded several boxes in the Brit’s nose hold.

“Yes, of course” we had unloaded it” came Norrie’s irritated and assured reply. A few minutes later, a signal arrived from Brize that 4,500 lbs, un-manifested and unaccounted for in the trim sheet, had been found in the nose hold of a Brit returning from Luqa and did anyone know about it? “Red-faced” signal back that we needed the kit met with a reply that it would be sent out on the next scheduled fight in a couple of days. That had no sooner been read and digested than a red hot “Immediate and Personal from the AOC 1 Gp” signal appeared overturning the Brize message and that it would be with us in a special flight in the time it took a Brit to return from Brize to Luqa. And so it did!

Never did hear how Norrie got on with the repercussions nor what had been said to the pilot whose pre-flight checks had not identified the un-manifested load. We did hear that some surprise had been registered by the crew at how long it had taken to gain height after rotation and that landing had been “interesting”. I suppose it says a lot for the inherent stability of the Brit that such an affair could be managed without much drama.

Footnote 1. I never did meet Norrie again to ask him about it but I did replace RHO Johnson at Sealand in 1986 – where his selective memory had allegedly not stored the tale.

Footnote 2. I mentioned above the excitable engineering officer. His stress was in part explained by his having failed to close the Land Rover door properly. At a point in the track to Sunspot, the road took an abrupt bend and a dive down about 10 feet to a lower level. As we belted down that bit, Richmond’s door opened and for a split second there was more of him outside the cab than inside it before he got his large frame back inside. Strange, he could not see the funny side of any of it.

From: Jeff Thomas, Llandrindod Wells, Powys

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

Happy new year to you and all the guys.

It was September 1961 at RAF Lyneham where I first encountered the magnificent Britannia. There were three of us new movers and we were sent on an ‘Air Experience’ flight. What was late information to us was that we were off to Gibraltar. I was just 18 that month and completely overwhelmed, so it was a case of following the guys around and fitting in wherever we could.

The operating crew were first class and we were well looked after, learning each step of the way. The flight was without incident and the approach into Gib was magnificent. All-in-all a very nice long weekend, some of it spent with the movers in the crown colony. The flight home went quick enough and the three of us had really gained ‘Air Experience’.

Best wishes,

Jeff Thomas

Subject: Memories of the Whispering Giant

Hi Tony,

Happy new year to you and all the guys.

It was September 1961 at RAF Lyneham where I first encountered the magnificent Britannia. There were three of us new movers and we were sent on an ‘Air Experience’ flight. What was late information to us was that we were off to Gibraltar. I was just 18 that month and completely overwhelmed, so it was a case of following the guys around and fitting in wherever we could.

The operating crew were first class and we were well looked after, learning each step of the way. The flight was without incident and the approach into Gib was magnificent. All-in-all a very nice long weekend, some of it spent with the movers in the crown colony. The flight home went quick enough and the three of us had really gained ‘Air Experience’.

Best wishes,

Jeff Thomas

On arrival at Lyneham, in Dec 1960, as there were no RAF courses covering the civilian equipment fitted to RAF Britannias - which had, after all, been designed with the world’s airlines in mind - I was to find myself dispatched afar, even deeper into the West Country. This time to Smiths Industries, in the heart of the beautiful Cotswold countryside. A timeless area in a region of rural calm. Thatched roofs and cottage gardens; butterflies and bumblebees kind of places. There were ancient churches, and the country pub; the very essence of all that is best in the English countryside.

Training complete, I was now about to begin a life living out of a suitcase. Not as bad as it sounds, for after the Sunderland, Valetta, Hastings, and other diverse types, the Britannia was a magnificent aeroplane. Certainly, technically far in advance of the Sunderland and Whirlwind. For instance, on the Britannia, there was no direct connection between control column, rudder pedals and control surfaces. Ailerons, elevators, and rudder were free-floating, controlled by trim tabs, and it was these that were connected to the control column. As for engine controls, the throttles were all electric - an Electrical Fitter and Flight Engineer’s nightmare. Yet when it came to the navigation department, we were a generation behind the V-Bombers.