Inside the British Operation - by Frank Pope

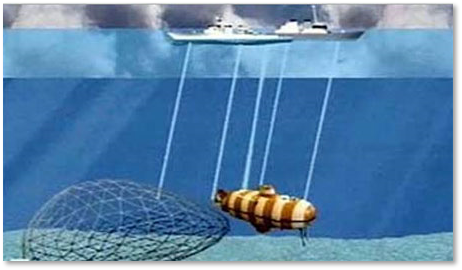

In August 2005, in a remote bay off the Kamchatka Peninsula in the far northeast of the Asian continent, a Russian Navy mini-submarine on a mission to a secret underwater facility came to an unexpected halt. In the darkness hundreds of feet below the surface, it had run into a web of cables. Attempts to escape only trapped it tighter. With seven men on board a vessel designed for four, the air quickly started to run out.

On the other side of the globe, the Royal Navy’s elite submarine rescue team were asleep, unaware of the drama that would soon overtake them. Five years previously an explosion had sunk the Russian nuclear submarine Kursk - they’d scrambled to help, but had been prevented from doing so by paranoid Russian authorities. A handful of sailors survived the initial blast but died a grim, claustrophobic death in their metallic tomb. In all, 118 men perished.

On the other side of the globe, the Royal Navy’s elite submarine rescue team were asleep, unaware of the drama that would soon overtake them. Five years previously an explosion had sunk the Russian nuclear submarine Kursk - they’d scrambled to help, but had been prevented from doing so by paranoid Russian authorities. A handful of sailors survived the initial blast but died a grim, claustrophobic death in their metallic tomb. In all, 118 men perished.

The crew trapped on board the mini-submersible AS28 had reason to hope this time would be different. President Putin had poured funds into new rescue equipment after the Kursk disaster. But as the hours ticked by, optimism faded. The only other submersible in the area was in pieces on the dockside and, when one of Putin’s brand-new rescue robots was deployed, an inexperienced pilot sent it through the ship’s propeller, severing the cable that linked the robot to the ship, rendering it useless. The Russians resorted to trying to snag the stricken sub with grappling hooks.

In the tough frontier town of Petropavlovsk, the wife of the vessel’s young pilot sensed something was wrong. She called the naval headquarters in Petropavlovsk, but the staff denied that there was any problem. That could have been the end of it, but once a local radio station got wind of the story the news rapidly went global.

In the tough frontier town of Petropavlovsk, the wife of the vessel’s young pilot sensed something was wrong. She called the naval headquarters in Petropavlovsk, but the staff denied that there was any problem. That could have been the end of it, but once a local radio station got wind of the story the news rapidly went global.

A computer-generated image shows AS-28 trapped on the Pacific floor being dragged with a trawling apparatus

When it reached the UK, Commander Ian Riches of the Submarine Rescue Service wasted no time in mobilising his men. He knew that every minute mattered. He was well-acquainted with a long history of underwater accidents, attempted rescues and failed escapes.

Although paid for and run by the Royal Navy, the men who crewed the SRS were civilians. Their training came from working in the brutal conditions of the North Sea as subsea engineers, vehicle pilots and surface support technicians for oil and gas companies. Their rough-and-ready appearance belied an unmatched expertise in pulling off difficult missions deep beneath the sea. As they pulled together their equipment, few believed that the Russians would agree to be assisted, or that they could get there in time.

Although paid for and run by the Royal Navy, the men who crewed the SRS were civilians. Their training came from working in the brutal conditions of the North Sea as subsea engineers, vehicle pilots and surface support technicians for oil and gas companies. Their rough-and-ready appearance belied an unmatched expertise in pulling off difficult missions deep beneath the sea. As they pulled together their equipment, few believed that the Russians would agree to be assisted, or that they could get there in time.

Meanwhile, Captain John Holloway, the naval attaché at the British Embassy in Moscow and an ex-submariner, was furiously working to persuade the Russians to accept assistance. He was not about to let this diplomatic opportunity slip away. For a long time he’d been working to build links between the Russian Navy and the Royal Navy, and a successful rescue mission could transform relations.

Time was already short. Estimates released by the Russian Navy varied wildly, with some saying the trapped men could last several days and others saying that they had only hours left. When Captain Holloway informed the Russian Ministry of Defence that the SRS could reach the trapped men within 36 hours if requested, a Russian vice-admiral called back immediately not only to accept, but to ask if the team could get there any faster.

Time was already short. Estimates released by the Russian Navy varied wildly, with some saying the trapped men could last several days and others saying that they had only hours left. When Captain Holloway informed the Russian Ministry of Defence that the SRS could reach the trapped men within 36 hours if requested, a Russian vice-admiral called back immediately not only to accept, but to ask if the team could get there any faster.

With their diplomatic invitation in place, the RAF scrambled aircraft, and a motley crew of oil-rig types and naval officers was soon assembled at Glasgow airport. As they loaded the kit into the C17 long-range military transport, the pilots were busy calculating a route none of them had ever flown, arcing up over the Russian Arctic to the Elizovo military airfield.

On the trapped submersible, only one canister of carbon-dioxide-absorbing and oxygen-releasing chemicals remained. The crew were huddled in the aft compartment of the tiny craft to try to keep warm. The captain was gasping badly in the foul air. He should never have been there, having lost a kidney and part of one lung during an earlier illness, but the usual commander was away. Most of the rest of the crew were young men with families. One by one they slipped into the forward compartment to write farewell notes.

On the trapped submersible, only one canister of carbon-dioxide-absorbing and oxygen-releasing chemicals remained. The crew were huddled in the aft compartment of the tiny craft to try to keep warm. The captain was gasping badly in the foul air. He should never have been there, having lost a kidney and part of one lung during an earlier illness, but the usual commander was away. Most of the rest of the crew were young men with families. One by one they slipped into the forward compartment to write farewell notes.

The C17 was the first foreign aircraft to land at the airbase outside Petropavlovsk. Riches and his men were ready to hit the ground as soon as the wheels stopped rolling, but they quickly ran into the systemic dysfunction at the heart of Russia’s armed forces.

With their compatriots gasping for air in the deep, dark sea, Air Force officials ordered the team to compile a detailed inventory of all their equipment for Customs. It would be the first of many maddening delays.

With their compatriots gasping for air in the deep, dark sea, Air Force officials ordered the team to compile a detailed inventory of all their equipment for Customs. It would be the first of many maddening delays.

When the team finally made it to the dock they found the ship allocated to them - a rusting military charter guarded by feral dogs. The UK’s rescue vehicle, known as Scorpio, was lifted off the dockside and dropped heavily on deck. The Russian crew had been trapped for almost 60 hours.

Stuart Gold, a Scottish civilian electrical engineer who ran all of Scorpio’s operations, set about preparing the vehicle. He had looked after Scorpio for more than a decade and knew its every last nut and bolt. But when he hooked Scorpio to the Russian ship’s electrical systems and turned it on, the vehicle was dead. Every screen was blank. He’d never seen anything like it.

With only five hours until the ship reached its goal, Gold calmly began to strip the machine and - with only minutes to spare - managed to fix the many connections that had come loose.

Stuart Gold, a Scottish civilian electrical engineer who ran all of Scorpio’s operations, set about preparing the vehicle. He had looked after Scorpio for more than a decade and knew its every last nut and bolt. But when he hooked Scorpio to the Russian ship’s electrical systems and turned it on, the vehicle was dead. Every screen was blank. He’d never seen anything like it.

With only five hours until the ship reached its goal, Gold calmly began to strip the machine and - with only minutes to spare - managed to fix the many connections that had come loose.

On station above the submersible at last, Gold launched the rescue vehicle. After long minutes in the dark water they glimpsed a vast metallic cylinder hanging in front of them. The structure was part of a top-secret array of underwater microphones built to listen out for enemy submarines as they criss-crossed the Pacific. Next to it was the red-and-white striped hull of the stricken submersible. Slowly, carefully, they began cutting the lines with remotely operated shears. Then, with only one more cable to cut, Scorpio’s underwater shears collided with the submersible and could no longer function. The team had no choice but to bring Scorpio back to the surface.

Inside the trapped vessel, lack of oxygen and the build-up of carbon dioxide meant the men could hardly move. They had now been inside for 70 hours. The stink of vomit, excrement and urine was overpowering. As they heard the whine of the foreign machine fade they were flooded with despair.

When Scorpio eventually returned the submarine looked lifeless. Once the last cable was cut it hung there, free but motionless. The team feared the worst. Then, slowly, AS28 began to rise. When it broke the surface huge cheers erupted from the assembled surface fleet. When a Russian launch towed it out of sight of the British team before the hatch was opened, Commander Riches assumed this meant that there was something the Russians wanted to hide. Then the call came through on the radio. All seven men were still alive. They’d done it.

When Scorpio eventually returned the submarine looked lifeless. Once the last cable was cut it hung there, free but motionless. The team feared the worst. Then, slowly, AS28 began to rise. When it broke the surface huge cheers erupted from the assembled surface fleet. When a Russian launch towed it out of sight of the British team before the hatch was opened, Commander Riches assumed this meant that there was something the Russians wanted to hide. Then the call came through on the radio. All seven men were still alive. They’d done it.

The rescued men were rushed ashore and bundled into a military ambulance. Their wives and families were waiting on the dockside but could only press their hands to the windows as the van sped off. Their debriefing was evidently severe, and any talk of their fear, suffering and farewell notes was banned. Only later did some wives speak up, prompted by the fact that their husbands were blamed for embarrassing the Russian Navy.

On the fleet of rescue ships the atmosphere was one of jubilation. The British crew were invited to the bridge of their vessel and the first vodka toast was drunk. For the next 12 hours they continued. For some the relief was overwhelming. Pete Nuttall, Scorpio’s pilot, was an RNLI volunteer in the UK and had recently been part of a failed attempt to rescue a father and son. As it became clear that seven fathers had been saved, he broke down in tears.

It wasn’t until months later that the British team met the men whose lives they had saved, when a documentary crew brought them back to Kamchatka. Despite the language barrier and never having met before, the reunion was emotional.

It wasn’t until months later that the British team met the men whose lives they had saved, when a documentary crew brought them back to Kamchatka. Despite the language barrier and never having met before, the reunion was emotional.

UKMAMS - once again FILO!

On 4 Aug 05 a Russian submarine, AS28, sent a signal of distress to the Nation, having become entangled in fishing nets off the coast of Petropavlovsk. The decision was made that the UK and USA would send rescue equipment and specialist rescue teams to assist in the safe recovery of 7 Russian submariners. It was believed that the crew on board only had 48 hrs of oxygen left, so the rapid reaction from the UK and USA was critical.

At approx 1030 hrs on 4 Aug 05 UKMAMS Ops received information regarding the mission; they then had the task of finding 4 team members who were available at short notice. The team consisted of 1 x FS C17 Supervisor (FS Tony Stock), 1 x Cpl (Cpl Alex Morgan), and 2 x SAC Movs Controllers (SAC Leon Muir and SAC Ross 'Eric' Bristow).

At approx 1030 hrs on 4 Aug 05 UKMAMS Ops received information regarding the mission; they then had the task of finding 4 team members who were available at short notice. The team consisted of 1 x FS C17 Supervisor (FS Tony Stock), 1 x Cpl (Cpl Alex Morgan), and 2 x SAC Movs Controllers (SAC Leon Muir and SAC Ross 'Eric' Bristow).

The team had approximately 11⁄2 hrs to pack for an operation which had no confirmed recovery date; we were then driven to RAF Brize Norton to meet and board C17 Flt 6564 to Yelizovo via Prestwick. Once the MAMS team arrived at Brize Norton we were met by Sgt 'Plug' Harvey with the information of what load we were expecting to collect at Prestwick. At 1315Z hrs we departed Brize Norton on the first leg of the journey, with an approximate flight time of one hour.

We were met at Prestwick by Cdr Iain Riches, RN, who gave further information of the task. The equipment arrived at the aircraft promptly, and with assistance from FS Steve Joyce and Cpl Robbie Collins (JATEU) we began building an assortment of pallets. The load consisted of:

1 x Control Cabin (triple pallet) 1 x Crane (double pallet) 1 x Winch (double pallet) 1 x Cabin (single pallet) 1 x Rov Submarine (single pallet) 10 x passengers (Rescue Team) with a total payload of 63000 lbs. After expediting the rapid turnround at Prestwick we pushed on towards Russia. The route took us east over Russia and 400 miles outside the North Pole. We arrived at Yelizovo at 0525Z hrs, so in terms of response time we were offloading in Russia within 20 hours from being notified, and 2 hours in front of the Americans

We were met at Prestwick by Cdr Iain Riches, RN, who gave further information of the task. The equipment arrived at the aircraft promptly, and with assistance from FS Steve Joyce and Cpl Robbie Collins (JATEU) we began building an assortment of pallets. The load consisted of:

1 x Control Cabin (triple pallet) 1 x Crane (double pallet) 1 x Winch (double pallet) 1 x Cabin (single pallet) 1 x Rov Submarine (single pallet) 10 x passengers (Rescue Team) with a total payload of 63000 lbs. After expediting the rapid turnround at Prestwick we pushed on towards Russia. The route took us east over Russia and 400 miles outside the North Pole. We arrived at Yelizovo at 0525Z hrs, so in terms of response time we were offloading in Russia within 20 hours from being notified, and 2 hours in front of the Americans

After the offload the rescue equipment was transported to the port of Petropavlovsk, which was a 1 1/2 hour truck journey from the airport. Time was running low for the submariners and every minute counted; each and every one of the teams involved in this operation played a vital part in the timings and it was critical no mistakes were made. With no communications between us and the rescue team we sat close by a TV set in a local tavern, and with the help of RAF Interpreter Sgt Martin Goodson we conquered the language barrier and watched the news for updates. After finding out that the rescue attempt was successful, we celebrated as the owner of the tavern thanked us with 2 bottles of his finest vodka and made a touching speech. Under the constant watchful eye of Boris, a leiutenant in the Russian Security Force, we left the tavern on a small expedition to a naturally heated swimming bath for a Sunday swim.

After the third day of being served mashed potato and meat for breakfast, lunch and dinner we were looking forward to the arrival of the freight for us to pack up and return to the UK.

The day finally arrived on 8 Aug 05 and we were all surprisingly eager and looking forward to Brize In-Flight Catering! We loaded the equipment and returned to the Russian barrack blocks for a good night's sleep.

The departure morning came and we were unexpectedly presented with more vodka and caviar, and a final thank you for our efforts, by a 2 Star Rear Admiral of the Pacific Fleet.

Thanks to the C17 crew and 99 Sqn, UKMAMS were once again 'First In - Last Out'

The day finally arrived on 8 Aug 05 and we were all surprisingly eager and looking forward to Brize In-Flight Catering! We loaded the equipment and returned to the Russian barrack blocks for a good night's sleep.

The departure morning came and we were unexpectedly presented with more vodka and caviar, and a final thank you for our efforts, by a 2 Star Rear Admiral of the Pacific Fleet.

Thanks to the C17 crew and 99 Sqn, UKMAMS were once again 'First In - Last Out'