One operation that will remain in the memories of all those who took part was Operation Lucan. East Pakistan had fought for its independence from West Pakistan for a number of years and now with it established as Bangladesh there were 200,000 POWs and refugees in the `wrong' country. Thousands of Bengalis in Pakistan wanted to be in Bangladesh. Equally non-Bengalis in Bangladesh felt they should be in Pakistan. The UK had agreed to assist in the UN repatriation scheme and Operation Lucan was launched. The operation started in December 1973 and during the few months it was due to run would witness the largest migration of refugees of all time. The operation was to involve an international effort financed and coordinated by the United Nations and the International Red Cross respectively. The operation was instigated as an humanitarian gesture to take 200,000 people to where they felt home to be - unfortunately this was not always to safety.

The need to move the refugees arose as a result of the Pakistan Bangladesh war which had resulted in the creation of the independent state of Bangladesh. Whilst this was very satisfying for the new government of Bangladesh, the war also served to confirm the less acceptable creation of many thousands of refugees. After the war, 100,000 Bengalis were stranded in Pakistan and conversely, 500,000 were camped in appalling conditions in the new Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan. The living conditions for all these people created through military conflict, and more natural meteorological and biological factors were heartbreaking. Floods, cyclones, murder, robbery and a raging cholera epidemic were all problems that beset the refugees, and many hundreds perished daily. The refugees were also forced to contend with constant starvation.

Those who remember the early years of the 70’s may recall the “Concert for Bangladesh” that formed just a part of a worldwide appeal for assistance. In answer to this call, the United Kingdom, in addition to a substantial sum of money, provided 2 Britannia aircraft, crews, and of course the ground handling staff. The political situation was far from stable, and after a series of tense negotiations the 2 Britannia aircraft left Brize Norton for Pakistan. The Soviet Union, probably as anxious to ensure contact was maintained with the new government of Bangladesh as they were to relieve suffering, also deployed transport aircraft to the area. Strangely, for the pre-Glasnost era of East-West relations, the British found themselves working alongside their Soviet counterparts who were operating Ilyushin 18 and TU134 aircraft. With the UK detachment, a four-man UKMAMS team were deployed to the area.

The team, led by Dave Barton, with Bob Turner, Jack Gordon and Hugh Curran, left Brize Norton on 27th October staging through Akrotiri, finally arriving in Karachi, Pakistan, the following day.

The airlift started the day after the MAMS team arrived with a 5am start to make an 8am take off. Whilst the MAMS team were in charge of coordinating the aircraft loads with regards to loading the aircraft and determining the payload available for passengers, the Red Cross were responsible for providing the passengers. The first few days were absolutely chaotic giving the team very little chance to even guess the numbers of passengers allocated to each flight by the Red Cross, and absolutely no hope of getting the baggage until long after it had gone. To be fair, the Red Cross had their backs against the wall with the enormity of the task and the lack of experience they had in this field of endeavour. The MAMS team set up a liaison and booking system for the refugees that was to prove an administrative boon for all the agencies involved, and it has become a standard for all subsequent operations of this type. The relief agencies ran what could be described as a passenger terminal from a large marquee at the side of Karachi airfield. Here the thousands of refugees would be delivered by truck from the camps, and here they would be carefully documented, allocated to a flight and manifested.

The airlift started the day after the MAMS team arrived with a 5am start to make an 8am take off. Whilst the MAMS team were in charge of coordinating the aircraft loads with regards to loading the aircraft and determining the payload available for passengers, the Red Cross were responsible for providing the passengers. The first few days were absolutely chaotic giving the team very little chance to even guess the numbers of passengers allocated to each flight by the Red Cross, and absolutely no hope of getting the baggage until long after it had gone. To be fair, the Red Cross had their backs against the wall with the enormity of the task and the lack of experience they had in this field of endeavour. The MAMS team set up a liaison and booking system for the refugees that was to prove an administrative boon for all the agencies involved, and it has become a standard for all subsequent operations of this type. The relief agencies ran what could be described as a passenger terminal from a large marquee at the side of Karachi airfield. Here the thousands of refugees would be delivered by truck from the camps, and here they would be carefully documented, allocated to a flight and manifested.

The aircraft were to operate a shuttle that ran between Karachi in Pakistan and Dacca (now Dhaka) in Bangladesh, with some lifts extending beyond Dacca to Chittagong. The refugees travelling to Bangladesh were, by and large, quite well off, inasmuch as they had some possessions, had been fed periodically, and had not been too ill treated. A call for volunteers to form a baggage party was always well responded to, and the UKMAMS team were often required to reduce the vast number of volunteers to more manageable proportions before loading could commence. It soon became apparent that the return journeys were arriving almost free of any form of baggage or personal effects, and suspecting a lack of efficiency in Dacca, the MAMS teams started to travel on the Britannia runs to evaluate the situation. On seeing both Dacca and Chittagong the movers were horrified at the conditions that people were kept in.

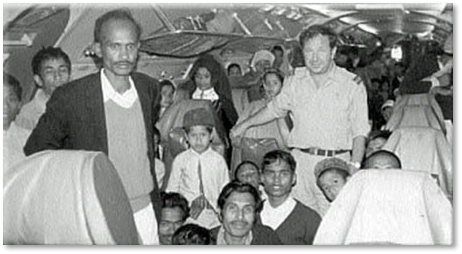

The UN and Red Cross officials certainly had an unenviable task trying to repatriate whole families together. In the words of one member of the team, “To obtain an accurate figure of the number of passengers on each aircraft we would try to count heads once the doors had shut. Even this had its problems as families of six or seven would huddle together on a triple seat with nothing but fear on the faces of those that could be seen. Most had never travelled on an aircraft before, and some would try to hide.

The two Loadmasters on each of the 2,600 mile flight did a marvellous job thinking only of their passengers and not for the first time forgetting the rule book. We gave what assistance we could but felt quite inadequate to deal with such a pathetic situation. Wherever possible seat belts were secured, oftentimes one belt around two or three wizened bodies. Drinks to the passengers were kept to a minimum (a ploy developed by several German airlines for more commercial reasons) to try and mitigate the inevitable air sickness that would occur even before takeoff. The passengers would be equally confused by the toilets and it was common for them to attempt natural bodily functions from the unnatural position of standing on the seat. This of course was not the most accurate method, and misses were more prevalent than hits. Some passengers tried, and failed, to reach the toilets, others stayed in seats, often out of fear.

It was the job of the ground crews back at Karachi to clear up the aircraft for the next trip, a task they were welcome to. Most of the refugees’ baggage consisted of small bundles of cloth containing what few possessions a family had Any money was converted into paan leaves , which whilst almost worthless in Bangladesh, fetched high price as a kind of chewing tobacco in Pakistan. A journalist from the Guardian (David Fairhall) coined the phrase, “Operation Heartbreak” as he witnessed the pathetic plight of the people. He wrote strong words of praise and confessed a deep admiration for the RAF personnel, who responded to the plight in any way that they could. He, like the detachment, realised that one in four of the refugees would die within a month of repatriation, which made watching them kissing the ground in gratitude even more poignant.

It was the job of the ground crews back at Karachi to clear up the aircraft for the next trip, a task they were welcome to. Most of the refugees’ baggage consisted of small bundles of cloth containing what few possessions a family had Any money was converted into paan leaves , which whilst almost worthless in Bangladesh, fetched high price as a kind of chewing tobacco in Pakistan. A journalist from the Guardian (David Fairhall) coined the phrase, “Operation Heartbreak” as he witnessed the pathetic plight of the people. He wrote strong words of praise and confessed a deep admiration for the RAF personnel, who responded to the plight in any way that they could. He, like the detachment, realised that one in four of the refugees would die within a month of repatriation, which made watching them kissing the ground in gratitude even more poignant.

So keen were some passengers to travel that one man boarded the aircraft from Karachi keeping it a secret that he had a broken leg rather than risk being left behind. This overwhelming desire to move west to east must seem strange when one considers that Pakistan is relatively prosperous whilst Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries in the world. It was undeniably sad to witness a local dog in Dacca rummaging in the aircraft rubbish bags for twice its daily food, and then to be followed by local children who would feed on what the dog had left behind.

The RAF’s part of the task came to an end on 3rd February 1974 when the two Britannia aircraft made their last departure from Karachi. At the end of the United Kingdom’s final act in this sad human tragedy, The RAF had flown 33,000 people each way across Asia. The departure of the RAF however did not spell the end of the effort. It was some consolation to t he departing team that other nations were scheduled to come so that the airlift could be continued. Despite the dirty and unglamorous nature of the task, and the sense of despair surrounding the whole operation, the UKMAMS teams were proud to have played a part however small. Sadly the participants knew that this time they were not helping to save lives, but simply giving the people the right to choose where they died.

The following was discovered in a publication which mentioned the airlift:

Air loadmaster Flight Sergeant John Grimwood sums it all up with a story: ‘One of the local baggage unloaders was emptying the belly hold of the few possessions of the refugees when the door came off its catch. The damper mechanism was U/S and the door came crashing down on his fingers cutting them clean off. I rushed to find the UN man who employed the local labour. ‘One of your locals has cut off his fingers,' I panted. ‘Don’t worry,' he replied, ‘I will get you another one straight away.' The injured loader was wheeled away on a trolley, screaming, and another took his place. How cheap life is in that part of the world.’

Air loadmaster Flight Sergeant John Grimwood sums it all up with a story: ‘One of the local baggage unloaders was emptying the belly hold of the few possessions of the refugees when the door came off its catch. The damper mechanism was U/S and the door came crashing down on his fingers cutting them clean off. I rushed to find the UN man who employed the local labour. ‘One of your locals has cut off his fingers,' I panted. ‘Don’t worry,' he replied, ‘I will get you another one straight away.' The injured loader was wheeled away on a trolley, screaming, and another took his place. How cheap life is in that part of the world.’