From: Len Bowen, Chisholm ACT

Subject: Memories of RAF Abingdon

Subject: Memories of RAF Abingdon

MEMORIES OF ABINGDON – THE SPIRITUAL HOME OF AIR MOVS

A contentious title perhaps, as some might see RAF Lyneham, the home of the ‘Shiny Fleet’ as the home of RAF movements, or even that Johnny-Come-Lately after the USAF were finished with it, Brize Norton, but I contend that Abingdon not only had the Air Movements Training School for many years (1963 - 1972), but also the Joint Air Transport Establishment (JATE) from 1968 to 1975. The Station was certainly my spiritual home as an Air Movements Officer, as I both started and finished my time as a RAF MOVO there. I could fill a book with memories of Abingdon, mostly happy but with a few sad overtones, so here goes.

I first arrived at Abingdon on 4th January 1965, fresh from my Equipment Officers’ Course at Upwood and no longer an Acting Pilot Officer. Supernumerary at Air Movements, waiting for my Senior Movements Course which didn’t start until about six weeks later. Despite being only a lowly Plt Off, I was welcomed and put under the wing of the Flight Sergeant in charge of Load Control. To my shame I cannot at this stage remember his name, but I do recall that he was a great mentor to somebody brand new in the movements game.

The first few weeks were a blur as I was introduced to our resident Beverleys (later the love of my life for three years in the Far East) and visiting Hastings. I had my first Beverley ride just a week after arriving, and it was certainly a ‘baptism of fire’. The following is an extract from a series of articles that have been printed in the Beverley Association magazine, ‘Mag Drop’ and elsewhere over the years:

FIRST BLOOD - WELL NEARLY!

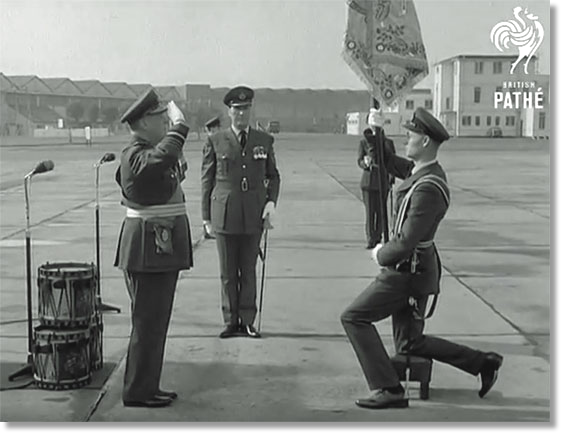

Significantly, my first ever Beverley flight, on 9 Jan 65, ended abruptly with an engine fire! I was by then a Pilot Officer, supernumerary with the Abingdon Air Movements Section awaiting my formal Air Movements Course. The Section was providing movements support for a Tactical Landing demo for some visiting foreign Brass, and, though not yet AMS-qualified, I went along for the ride as unskilled labour. The idea was that we would do a steep tactical approach, land on the grass next to our visitors then … max reverse pitch and brakes … doors open … ramps down … two Ferret armoured cars offloaded … ramps up … doors closed … short field take-off; all in two minutes. Not a bad trick when you remember that the ramps, each weighing over 100 lb, had to be lowered on the cable, man-handled out into position, then the operation reversed before the doors could be closed for take-off.

My (informal) log book shows that we got airborne at 0930 in XB269, with Major Van-Haven, a USAF Exchange pilot, as Captain. We landed 10 minutes later to practise our demo. Whether the Major was a bit heavy-handed with the reverse pitch, or it was just the old Centaurus play-up that I was to come to know and love, I do not know. What I do know is that as soon as we were on the deck and the Skipper hit reverse, there was a very loud bang and a bloody great cloud of smoke from, I think, No 4. As planned for the demo, we ran off the aircraft …. but instead of deploying the ramps and the two Ferrets, we just kept running, closely followed by the Air Quartermaster and then the rest of the crew!

As the smoke cleared, we realised that there wasn’t a major fire, just a blown cylinder – or two. The RAF Fire Crew treated the engine to a dose of foam then we got back aboard and off-loaded the Ferrets in slow time. We completed the TL Demo later that morning in 150 without further incident. Welcome to the wonderful world of the Beverley, Len!

I first arrived at Abingdon on 4th January 1965, fresh from my Equipment Officers’ Course at Upwood and no longer an Acting Pilot Officer. Supernumerary at Air Movements, waiting for my Senior Movements Course which didn’t start until about six weeks later. Despite being only a lowly Plt Off, I was welcomed and put under the wing of the Flight Sergeant in charge of Load Control. To my shame I cannot at this stage remember his name, but I do recall that he was a great mentor to somebody brand new in the movements game.

The first few weeks were a blur as I was introduced to our resident Beverleys (later the love of my life for three years in the Far East) and visiting Hastings. I had my first Beverley ride just a week after arriving, and it was certainly a ‘baptism of fire’. The following is an extract from a series of articles that have been printed in the Beverley Association magazine, ‘Mag Drop’ and elsewhere over the years:

FIRST BLOOD - WELL NEARLY!

Significantly, my first ever Beverley flight, on 9 Jan 65, ended abruptly with an engine fire! I was by then a Pilot Officer, supernumerary with the Abingdon Air Movements Section awaiting my formal Air Movements Course. The Section was providing movements support for a Tactical Landing demo for some visiting foreign Brass, and, though not yet AMS-qualified, I went along for the ride as unskilled labour. The idea was that we would do a steep tactical approach, land on the grass next to our visitors then … max reverse pitch and brakes … doors open … ramps down … two Ferret armoured cars offloaded … ramps up … doors closed … short field take-off; all in two minutes. Not a bad trick when you remember that the ramps, each weighing over 100 lb, had to be lowered on the cable, man-handled out into position, then the operation reversed before the doors could be closed for take-off.

My (informal) log book shows that we got airborne at 0930 in XB269, with Major Van-Haven, a USAF Exchange pilot, as Captain. We landed 10 minutes later to practise our demo. Whether the Major was a bit heavy-handed with the reverse pitch, or it was just the old Centaurus play-up that I was to come to know and love, I do not know. What I do know is that as soon as we were on the deck and the Skipper hit reverse, there was a very loud bang and a bloody great cloud of smoke from, I think, No 4. As planned for the demo, we ran off the aircraft …. but instead of deploying the ramps and the two Ferrets, we just kept running, closely followed by the Air Quartermaster and then the rest of the crew!

As the smoke cleared, we realised that there wasn’t a major fire, just a blown cylinder – or two. The RAF Fire Crew treated the engine to a dose of foam then we got back aboard and off-loaded the Ferrets in slow time. We completed the TL Demo later that morning in 150 without further incident. Welcome to the wonderful world of the Beverley, Len!

After that rather interesting introduction, the rest of the next six months passed quite quickly. As I say, I could fill a book, but here are just a few highlights.

• There was a mad wee Welsh HM Customs officer who frequently met the aircraft returning from overseas. The first thing you did when you knew he was on shift was to find out how Cardiff City Football Club had gone over the weekend. If City had won, the customs clearance was a breeze, but if City had lost – watch out all inbound passengers! Early one Sunday morning after Cardiff City had gone down in a resounding defeat the afternoon before, I saw him make a young squaddie off an overnight Bev flight from Germany drink at least half a large bottle of warm gin before he would let the young lad through. His bloody-minded reasoning? The bottle capacity exceed the ‘duty free’ entitlement, but the alcohol could not be disposed of on British soil by pouring half down the (English) toilet as it had not cleared customs; neither could the bottle just be surrendered as he (‘Taffy the Customs’) did not have a Bond Store in which to securely hold said alcohol. As I recall he quoted any number of other HM Customs rules and regs while the young bloke gamely slugged more and more of the warm gin “No, Boyohh, that’s not nearly down enough to meet your entitlement”. When the kid was about to throw up all over the PAX Terminal floor Taffy relented, and under the watchful eye of an RSM meeting flight, the lad was helped off to one of the waiting Army trucks. The RSM sensibly seated him by the tailgate, and I often wonder if (a) he made it out of the Abingdon Main gate before he spewed? and (b) if he ever touched gin again in his life?

• There was a mad wee Welsh HM Customs officer who frequently met the aircraft returning from overseas. The first thing you did when you knew he was on shift was to find out how Cardiff City Football Club had gone over the weekend. If City had won, the customs clearance was a breeze, but if City had lost – watch out all inbound passengers! Early one Sunday morning after Cardiff City had gone down in a resounding defeat the afternoon before, I saw him make a young squaddie off an overnight Bev flight from Germany drink at least half a large bottle of warm gin before he would let the young lad through. His bloody-minded reasoning? The bottle capacity exceed the ‘duty free’ entitlement, but the alcohol could not be disposed of on British soil by pouring half down the (English) toilet as it had not cleared customs; neither could the bottle just be surrendered as he (‘Taffy the Customs’) did not have a Bond Store in which to securely hold said alcohol. As I recall he quoted any number of other HM Customs rules and regs while the young bloke gamely slugged more and more of the warm gin “No, Boyohh, that’s not nearly down enough to meet your entitlement”. When the kid was about to throw up all over the PAX Terminal floor Taffy relented, and under the watchful eye of an RSM meeting flight, the lad was helped off to one of the waiting Army trucks. The RSM sensibly seated him by the tailgate, and I often wonder if (a) he made it out of the Abingdon Main gate before he spewed? and (b) if he ever touched gin again in his life?

• I attach a couple of photos of the Abingdon ‘pan’ awash with Hastings.

April 1965 saw ‘Exercise FAST MOVE’, a practice reinforcement of Northern Ireland – shades of things to come. Abingdon AMS ran 24 hour shifts for five days straight – my first but by no means my last exposure to the realities of real air movements work. This period also marked my introduction to the sheer luxury of a hot chip butty dripping in butter and gravy at 03:00, eighteen hours into a 24-hour shift - no OH&S or ‘safe duty periods’ back then.

The exercise also taught me the importance of ‘DUFF / NO DUFF’ on exercise signals, as we received a message stating that the next Hastings inbound from Aldergrove had a Cat 1 spinal injury MEDEVAC on board. No indication that this was not a genuine casualty, so when the aircraft arrived at two in the morning we had an RAF ambulance, the Station Senior Medical Officer and his team and a spinal unit from Oxford’s Radcliffe Hospital waiting on the pan. When the ‘EXERCISE DUFF’ casualty walked off the aircraft on his own, he – and later the Exercise Control staff – were not greeted with the enthusiasm that they though that they deserved! Nor was the RAF particularly popular with the Radcliffe Hospital spinal team who had been roused from their beds in the wee small hours to handle what they expected to be a critical case. I was too junior to ever hear what the aftermath was but I would suggest that in Australian parlance, it took more than ‘a couple of cartons of cans’ to placate the civvy docs and nurses.

April 1965 saw ‘Exercise FAST MOVE’, a practice reinforcement of Northern Ireland – shades of things to come. Abingdon AMS ran 24 hour shifts for five days straight – my first but by no means my last exposure to the realities of real air movements work. This period also marked my introduction to the sheer luxury of a hot chip butty dripping in butter and gravy at 03:00, eighteen hours into a 24-hour shift - no OH&S or ‘safe duty periods’ back then.

The exercise also taught me the importance of ‘DUFF / NO DUFF’ on exercise signals, as we received a message stating that the next Hastings inbound from Aldergrove had a Cat 1 spinal injury MEDEVAC on board. No indication that this was not a genuine casualty, so when the aircraft arrived at two in the morning we had an RAF ambulance, the Station Senior Medical Officer and his team and a spinal unit from Oxford’s Radcliffe Hospital waiting on the pan. When the ‘EXERCISE DUFF’ casualty walked off the aircraft on his own, he – and later the Exercise Control staff – were not greeted with the enthusiasm that they though that they deserved! Nor was the RAF particularly popular with the Radcliffe Hospital spinal team who had been roused from their beds in the wee small hours to handle what they expected to be a critical case. I was too junior to ever hear what the aftermath was but I would suggest that in Australian parlance, it took more than ‘a couple of cartons of cans’ to placate the civvy docs and nurses.

• Unfortunately I was on duty at AMS Abingdon when Hastings TG577 crashed at Little Baldon just south of Abingdon on 6th July 1965 with the loss of all 41 aboard. I was directly involved in the aftermath of the crash on the Standing Committee of Adjustment, which meant much much more hands-on practical work than I would have cared for at the time. I won’t go into details even now, but suffice it to say that it ensured that I could handle anything – anything – that was thrown at me in my next three years in the Far East at Labuan Air Movements Section, up country during ‘Confrontation’, and later on FEAF MAMS. No such thing as PTSD or counselling back then, just several very stiff Scotches in the bar each evening, and not being able to face any cooked meat put in front of me at meal times for about a fortnight. Someday I will tell how some years later I extracted a Mover’s revenge on the senior officer who threw me into the deep end of the clean-up and clear-up of the crash, simply because he, having been given the job, couldn’t handle the sight of blood and gore “Look Len, you’re just a new young (Pilot) Office. You don’t want to be involved in the detailed paper-work do you? How about you just deal with the practical side, OK?” “Yes, Sir”. Took me seven years to even the score, but that is most certainly another story for another time.

• To end the tales of my first sojourn at Abingdon at a lighter and happier note, however, I will recount the story of the RAF Abingdon Officers’ Mess ‘Top Gear’ stable. Remember that this was still 1965, and we weren’t paid a great deal, however that didn’t stop we young and single officers having ‘interesting’ cars. The living-in members’ car park at the back of the Mess included, amongst other gems, a Mk V Jaguar (mine, cost me fifty quid) a Mk VI Bentley (cost him sixty), an Alvis Speed 20, a Sunbeam Talbot III saloon, a Triumph TR2, an MG TD and – belonging to a plutocratic Bev Sqn pilot just back from a tour in Aden – an Austin Healey 3000. You see, back then nobody wanted ‘old’ cars. Everyone wanted the modern GT Cortinas, Mini Coopers and the like. Result was that you could pick up the older classics for a song - and we did. Most summer Sundays we’d form a convoy – with girlfriends if we were lucky; I never was, but more of that later – off the Station and along the Oxford By-Pass to the ‘Trout Inn’ at Godstow.

Anyone familiar with the ‘Inspector Morse’ TV series will recognise the ‘Trout’. Rushing river over the weir, peacocks in the garden and a beautiful old ‘snug’ if it rained . If you could find – and afford – the line-up of cars from the Abingdon Officers’ Mess now you could mount a sale at Christies all on your own, but back then it was just fun to drive out to a classic English pub in a classic car (though we didn’t know they were classics then) with the sunroof open or the top down, and the wind and sun in the hair. Happy carefree – and relatively inexpensive – days!

17th July 1965 saw me leaving Abingdon for a brief period of embarkation leave, en-route to Labuan in North Borneo/Sabah for a year as one of the two DAMOs there. Ironically my embarkation leave coincided with my father’s dis-embarkation leave after a year as an Air Traffic Controller at Kuching in Sarawak. Well done the MoD(AIR) posters – though I’m not sure that the Royal Air Force, President Surkano and his ‘Confrontation’ or anything else could have coped with two Bowens in Borneo at the same time!

January 1973 had me back at Abingdon as a Project Officer with the Joint Air Transport Establishment (JATE). Arriving at our Married Quarter on Willow Tree Close with a new Fiat 124 Spec T car and an even newer wife. Married on 2nd September 1972, Penny and I were expecting a nice long Mediterranean holiday with my posting as Passenger Officer at AMS RAF Luqa, when we – and many like us – were summarily disestablished and short-toured when Luqa went from 24/7 operations to a five day week / normal working hours.

Notwithstanding the trauma – and the financial implications (the new Fiat lasted just six months to satisfy in-bound customs requirements) – of an abruptly-curtailed overseas tour, I was glad to be posted back at Abingdon into a job I wanted and had requested.

• To end the tales of my first sojourn at Abingdon at a lighter and happier note, however, I will recount the story of the RAF Abingdon Officers’ Mess ‘Top Gear’ stable. Remember that this was still 1965, and we weren’t paid a great deal, however that didn’t stop we young and single officers having ‘interesting’ cars. The living-in members’ car park at the back of the Mess included, amongst other gems, a Mk V Jaguar (mine, cost me fifty quid) a Mk VI Bentley (cost him sixty), an Alvis Speed 20, a Sunbeam Talbot III saloon, a Triumph TR2, an MG TD and – belonging to a plutocratic Bev Sqn pilot just back from a tour in Aden – an Austin Healey 3000. You see, back then nobody wanted ‘old’ cars. Everyone wanted the modern GT Cortinas, Mini Coopers and the like. Result was that you could pick up the older classics for a song - and we did. Most summer Sundays we’d form a convoy – with girlfriends if we were lucky; I never was, but more of that later – off the Station and along the Oxford By-Pass to the ‘Trout Inn’ at Godstow.

Anyone familiar with the ‘Inspector Morse’ TV series will recognise the ‘Trout’. Rushing river over the weir, peacocks in the garden and a beautiful old ‘snug’ if it rained . If you could find – and afford – the line-up of cars from the Abingdon Officers’ Mess now you could mount a sale at Christies all on your own, but back then it was just fun to drive out to a classic English pub in a classic car (though we didn’t know they were classics then) with the sunroof open or the top down, and the wind and sun in the hair. Happy carefree – and relatively inexpensive – days!

17th July 1965 saw me leaving Abingdon for a brief period of embarkation leave, en-route to Labuan in North Borneo/Sabah for a year as one of the two DAMOs there. Ironically my embarkation leave coincided with my father’s dis-embarkation leave after a year as an Air Traffic Controller at Kuching in Sarawak. Well done the MoD(AIR) posters – though I’m not sure that the Royal Air Force, President Surkano and his ‘Confrontation’ or anything else could have coped with two Bowens in Borneo at the same time!

January 1973 had me back at Abingdon as a Project Officer with the Joint Air Transport Establishment (JATE). Arriving at our Married Quarter on Willow Tree Close with a new Fiat 124 Spec T car and an even newer wife. Married on 2nd September 1972, Penny and I were expecting a nice long Mediterranean holiday with my posting as Passenger Officer at AMS RAF Luqa, when we – and many like us – were summarily disestablished and short-toured when Luqa went from 24/7 operations to a five day week / normal working hours.

Notwithstanding the trauma – and the financial implications (the new Fiat lasted just six months to satisfy in-bound customs requirements) – of an abruptly-curtailed overseas tour, I was glad to be posted back at Abingdon into a job I wanted and had requested.

JATE by then was a substantial establishment with a One-Star rotational Commandant (of whom more later) and several separate trials and projects Wings – Rotary, Air Drop and Air Land being just three. I was posted to the Air Land Wing where our responsibility was the design and development of loading and lashing schemes for all new vehicles and equipment entering British military service. Usually one or more experienced Air Movements Officers and SNCOs worked out the schemes, then our ‘Mk 1 Eyeball’ ideas were checked by either an RAF or a civilian Engineering Officer who was expert in stress factors and chain angles and strengths. Ninety nine times out of one hundred we all agreed on the scheme, and the necessary loading and lashing diagrams were produced and promulgated.

From time to time we also worked on the dangerous air cargo aspect of the movements game, including advice and assistance with the follow-up on accident and incident investigation. This gave rise to an interesting encounter some years later when I was doing my RAAF Movements Course at the Air Transport and Development Unit (AMTDU) at RAAF Richmond in 1979. One of our AMTDU Warrant Officer Air Loadmaster (ALM) instructors glossed over the dangers of transporting mercury in incorrect packaging in what I considered a really cavalier manner.

While obviously not challenging him in front of the class, I later took him aside and showed him a copy of a JATE Report – I knew such reports were shared with all our Commonwealth Air Force equivalent organisations - on an incident at RAF Lyneham when a Britannia was effectively Cat 5’d when an incorrectly labeled and loaded met barometer spilt several pounds of mercury onto the floor of the freight bay, which then reacted with the airframe aluminum and ate away a very large portion of the aircraft structure. One of the signators to the final report was one ‘Flight Lieutenant J.L. Bowen, Task Officer JEPS Air Land Wing’. WOFF ‘Shorty’ Heffernan wouldn’t speak to me for several years afterwards, even when I became Senior Movements Officer at RAAF Base Richmond in mid-1981 and he was back on one of the Richmond-based Herc squadrons! Nobody, especially a very senior WOFF ALM, likes to be proved wrong, even in private!

“Meanwhile, back at the ranch”. Our Air Land Wing hangar was at the far end of the station, just behind the Belfast servicing hangar, and while just a short walk from my MQ, it was a fair hike across to the NAAFI, the post office and so on. We usually used an old ex-loading tests & trials Ferret armoured car as an unofficial ‘staff car’ round the place to save walking, and once you got used to the odd gears and the laid-back steering wheel, it was the quickest and easiest way round the place especially in wet weather. From time to time we had more interesting vehicles in for loading trials, and I recall doing a ‘NAAFI Run’ one day in a brand new Fox armoured car complete with 30 mm RARDEN cannon. No trouble parking, or being questioned by the RAF Police for travel authorisation.

Talking of travel, by early 1974 soon-to-be our first son, Callum, was starting to make his appearance felt, and Penny was regularly travelling to the RAF Hospital at Wroughton for pre-natal checks and tests. By then for very pressing financial reasons (“Curse you MoD(AIR) for your ‘short tour’ decisions!”) our nice new Maltese-bought Fiat had had to be replaced with a rather tired Mk1 Cortina, and as Penny’s pregnancy progressed, she was less and less happy to drive to Wroughton herself. As a result in February ‘74 I was driving her to the hospital for a routine check-up, when we were stopped on the M4 for, of all things, a traffic survey. All the westbound vehicles were being slowed down and funneled into one lane by the police, where several university students from Bristol and Oxford were wielding clip-boards. We pulled up at a young pimply lad. “Good morning sir. May I ask where you are headed and the reason for your journey?” “Yes, we are heading for the RAF hospital at Wroughton” and, pointing across to a rather bulging Penny, rather un-necessarily added “My wife is having a baby …….” I had intended to continue “….in three months” but got no further.

From time to time we also worked on the dangerous air cargo aspect of the movements game, including advice and assistance with the follow-up on accident and incident investigation. This gave rise to an interesting encounter some years later when I was doing my RAAF Movements Course at the Air Transport and Development Unit (AMTDU) at RAAF Richmond in 1979. One of our AMTDU Warrant Officer Air Loadmaster (ALM) instructors glossed over the dangers of transporting mercury in incorrect packaging in what I considered a really cavalier manner.

While obviously not challenging him in front of the class, I later took him aside and showed him a copy of a JATE Report – I knew such reports were shared with all our Commonwealth Air Force equivalent organisations - on an incident at RAF Lyneham when a Britannia was effectively Cat 5’d when an incorrectly labeled and loaded met barometer spilt several pounds of mercury onto the floor of the freight bay, which then reacted with the airframe aluminum and ate away a very large portion of the aircraft structure. One of the signators to the final report was one ‘Flight Lieutenant J.L. Bowen, Task Officer JEPS Air Land Wing’. WOFF ‘Shorty’ Heffernan wouldn’t speak to me for several years afterwards, even when I became Senior Movements Officer at RAAF Base Richmond in mid-1981 and he was back on one of the Richmond-based Herc squadrons! Nobody, especially a very senior WOFF ALM, likes to be proved wrong, even in private!

“Meanwhile, back at the ranch”. Our Air Land Wing hangar was at the far end of the station, just behind the Belfast servicing hangar, and while just a short walk from my MQ, it was a fair hike across to the NAAFI, the post office and so on. We usually used an old ex-loading tests & trials Ferret armoured car as an unofficial ‘staff car’ round the place to save walking, and once you got used to the odd gears and the laid-back steering wheel, it was the quickest and easiest way round the place especially in wet weather. From time to time we had more interesting vehicles in for loading trials, and I recall doing a ‘NAAFI Run’ one day in a brand new Fox armoured car complete with 30 mm RARDEN cannon. No trouble parking, or being questioned by the RAF Police for travel authorisation.

Talking of travel, by early 1974 soon-to-be our first son, Callum, was starting to make his appearance felt, and Penny was regularly travelling to the RAF Hospital at Wroughton for pre-natal checks and tests. By then for very pressing financial reasons (“Curse you MoD(AIR) for your ‘short tour’ decisions!”) our nice new Maltese-bought Fiat had had to be replaced with a rather tired Mk1 Cortina, and as Penny’s pregnancy progressed, she was less and less happy to drive to Wroughton herself. As a result in February ‘74 I was driving her to the hospital for a routine check-up, when we were stopped on the M4 for, of all things, a traffic survey. All the westbound vehicles were being slowed down and funneled into one lane by the police, where several university students from Bristol and Oxford were wielding clip-boards. We pulled up at a young pimply lad. “Good morning sir. May I ask where you are headed and the reason for your journey?” “Yes, we are heading for the RAF hospital at Wroughton” and, pointing across to a rather bulging Penny, rather un-necessarily added “My wife is having a baby …….” I had intended to continue “….in three months” but got no further.

The student dropped his clipboard, grabbed the nearest cop and yelled something in his ear. Next thing I knew there was a shiny new Ford Three Litre Capri police highway pursuit car in front of me with all lights flashing and a young Constable shouting in my ear to “Follow that car, sir, he’ll see you right!” Well, I did manage to “… follow that car…” all the way to the Wroughton main gate, but keeping up with a 3 litre Capri in an elderly Mk 1 Cortina took all of my driving skill learnt in motor sport competitions in Singapore and Malta - and also resulted in the urgent need for an engine replacement for the Cortina very shortly afterwards. Surprisingly, my Hanna Mikkanen (look him up, son) impression didn’t bring on any complications with Penny and the first new Bowen, Callum Lennox, arrived in a normal way at Wroughton later that year on 24th May.

Most of the loading trials at JATE were pretty routine, but every now and again something unusual came up. In late August 1974 we were tasked to trial a special container which would be used to carry a solid fuel Stonechat rocket motor to Woomera in Australia by RAF Hercules for a launch trial. The container was 36 ft long, about 8 ft square and was bolted firmly onto the Herc roller conveyer system. After some adjustments all round, the loading trial was a success and 24th September 1974 saw me flying from Tengah to Darwin as Project Officer for the task en-route to deliver the beast to Woomera,. The load was so big that once aboard it was impossible to reach the rear of the aircraft from the front past the container, so my JATE team and I had pre-positioned at Singapore by VC10 on the 18th, but the Herc needed an engine change on arrival at Tengah, and it was not until the 24th that we got away heading for ‘The Land Down Under’. The stay at Tengah had caused some problems, as did I mention that Stonechat had an NEQ of 9,250 lb of solid rocket fuel? No? Well it had, and this caused some considerable consternation with the Republic of Singapore Air Force as to where to safely park the Herc while the engine change was effected. The huge NEQ also caused similar consternation at Royal Australian Air Force Base Darwin, because when we landed there supposedly only to over-night before continuing on to Woomera, the spinner on No 2 engine detached from the aircraft. It had been improperly refitted at Tengah, and came loose in flight somewhere over the Timor Sea. The skipper, Flt Lt Roger Payne, who was actually an Australian serving with the RAF, shut down the engine and we landed at Darwin with a declared emergency. When the spinner finally fell off on landing it nearly decapitated the Aussie Air Force fireman standing up behind the foam gun on the fire tender chasing us down the runway. After some kerfuffle we got the bird parked way way way off at the far end of the Darwin Base, where it stayed until we could ‘borrow’ a new spinner from the RAAF at Richmond. I think that they were only too keen to lend us the part to see the back of us and our 9,000+ lb NEQ load. There were several other ‘fun’ issues with this JATE Task, but for now “What happens down route stays down route”.

Meanwhile back at Abingdon Penny was having to cope on her own with a new baby – and having all the floors of the MQ ripped up for the installation of central heating, and holes drilled in the walls for the insertion of cavity insulation. Always happens when the husband is down route, but fortunately Penny had (and still has) a close cousin who has a large house near Woodstock, so she could finally seek sanctuary with Janet until I finally got home on October 1st, sun-burnt and laden with ‘duty free’ and a toy koala named Roger, after the Herc skipper, for Callum. Small compensation for the trauma that Penny had had to handle largely on her own, but she did so like a true Service wife, and we are still together 46 years after the event.

About mid-tour there must have been something in the air at Abingdon that made odd things happen. First (though I may have got my chronology wrong), we had the MQ Peeping Tom, then the heavy breather on the station phone system and then we had the Parachute School course that didn’t happen.

Most of the loading trials at JATE were pretty routine, but every now and again something unusual came up. In late August 1974 we were tasked to trial a special container which would be used to carry a solid fuel Stonechat rocket motor to Woomera in Australia by RAF Hercules for a launch trial. The container was 36 ft long, about 8 ft square and was bolted firmly onto the Herc roller conveyer system. After some adjustments all round, the loading trial was a success and 24th September 1974 saw me flying from Tengah to Darwin as Project Officer for the task en-route to deliver the beast to Woomera,. The load was so big that once aboard it was impossible to reach the rear of the aircraft from the front past the container, so my JATE team and I had pre-positioned at Singapore by VC10 on the 18th, but the Herc needed an engine change on arrival at Tengah, and it was not until the 24th that we got away heading for ‘The Land Down Under’. The stay at Tengah had caused some problems, as did I mention that Stonechat had an NEQ of 9,250 lb of solid rocket fuel? No? Well it had, and this caused some considerable consternation with the Republic of Singapore Air Force as to where to safely park the Herc while the engine change was effected. The huge NEQ also caused similar consternation at Royal Australian Air Force Base Darwin, because when we landed there supposedly only to over-night before continuing on to Woomera, the spinner on No 2 engine detached from the aircraft. It had been improperly refitted at Tengah, and came loose in flight somewhere over the Timor Sea. The skipper, Flt Lt Roger Payne, who was actually an Australian serving with the RAF, shut down the engine and we landed at Darwin with a declared emergency. When the spinner finally fell off on landing it nearly decapitated the Aussie Air Force fireman standing up behind the foam gun on the fire tender chasing us down the runway. After some kerfuffle we got the bird parked way way way off at the far end of the Darwin Base, where it stayed until we could ‘borrow’ a new spinner from the RAAF at Richmond. I think that they were only too keen to lend us the part to see the back of us and our 9,000+ lb NEQ load. There were several other ‘fun’ issues with this JATE Task, but for now “What happens down route stays down route”.

Meanwhile back at Abingdon Penny was having to cope on her own with a new baby – and having all the floors of the MQ ripped up for the installation of central heating, and holes drilled in the walls for the insertion of cavity insulation. Always happens when the husband is down route, but fortunately Penny had (and still has) a close cousin who has a large house near Woodstock, so she could finally seek sanctuary with Janet until I finally got home on October 1st, sun-burnt and laden with ‘duty free’ and a toy koala named Roger, after the Herc skipper, for Callum. Small compensation for the trauma that Penny had had to handle largely on her own, but she did so like a true Service wife, and we are still together 46 years after the event.

About mid-tour there must have been something in the air at Abingdon that made odd things happen. First (though I may have got my chronology wrong), we had the MQ Peeping Tom, then the heavy breather on the station phone system and then we had the Parachute School course that didn’t happen.

Now if in the unlikely situation you were a peeping tom going round the married patch looking in through the curtains in the hope of seeing a young wife or daughter, would you pick a night the station was on full BIKINI RED? Thought not, but he did. I really can’t remember the date, but I believe that Abingdon was the first mainland RAF station to go onto a full BIKINI RED ALERT status. Mid-morning the station hierarchy received confirmed and authenticated advice that the IRA were really going to pay us a call. This was after Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland and the Para Regiment were not in the Irish Top Ten at the time. Word was out that Paddy wanted to hit the Paras, but Aldershot was too hard a target so they were after the Parachute School at Abingdon. We all got the message about lunch time, and the RAF Regiment QRA mob flew in from Catterick mid afternoon in three Hercs In the meantime everybody was on full alert and my station rifle team learnt that being part of the team wasn’t just so that you got ten days a year away at Bisley, but again, another story.

As a result when all the station personnel finally stood down and left it to the professionals, most of us were still ‘tooled up’. About eight that evening there was a knock on our back door (no phones in the MQs in those days – at least not at Abingdon) and the teenage daughter from three doors down said that she thought that there was somebody in their back garden. A couple of walkie-talkie calls up and down the line of MQs, and all doors opened, lights on and three of us outside ‘loaded for bear’, as the Yanks say. I was carrying my own personal 9mm Browning; four doors down my mate had a double barreled 12 Bore and across the back was a Flt Lt Para School Instructor (PJI – remember that acronym) who worked with unusual people who wore sandy coloured berets, and who came home at weekends with a small black case marked ‘H&K’, had out the contents by the way of an MP5. Sure enough there in the garden lights was a young bloke on his knees with his fly open and in ‘a compromising position’ looking through a ground floor window in the young neighbour’s MQ. Seeing the three of us all out in the lights he took off like a gazelle over the low fences between the back MQ gardens. As clearly he wasn’t a one-man Provo hit squad we all let him go without a shot fired, and all would have been well if round the corner at the end of Willow Tree Close had not come an RAF Regiment Land Rover, top down and set up for full counter-terrorist ops with every one of the Rock Apes armed to the teeth. All they saw was three blokes in uniform pointing an assortment of weapons at a running fugitive. Fortunately for said fugitive at that moment, probably startled by the Land Rover’s lights he caught his foot on the last low fence and went a-over-t right in front of the Regiment boys. Now don’t let them tell you that the human body cannot soil itself while running and jumping a fence. When last seen by us the miscreant was zip-tied and sitting on the tail gate of the Land Rover while all five of the Regiment blokes were in or standing on the front seats.

After he was taken back to the Guard Room and hosed down, it transpired that he was a young Corporal from the station Orderly Room who had a lot of trouble meeting and connecting with girls, and in his job he knew which MQ was occupied by either young wives with husbands away on detachment or by families with teen-age daughters. I believe that he was given a psychiatric discharge, and the potential for ‘The Gun Fight at Willow Tree Close’ never came up.

The next incident was even more stupid. Back then the station still had a manual telephone exchange manned by young WRAF airwomen. Shortly after the peeping tom incident (will they never learn?) there was a ‘heavy breather’ who used to phone up the station PBX in the wee small hours, and when the girl alone in the exchange answered, when into his heavy breathing and panting routine – though never a word was spoken. Needless to say this was really frightening the young girls, but their NCO, a more worldly-wise Corporal, took it in hand so to speak. She rostered herself on for the late shift and sure enough, the heavy breather came on line shortly after midnight a couple of days later. Instead of hanging up the Cpl responded “Ooh you do sound nice and exciting. Are you up for a good time?” She led him on a bit more as the breathing got heavier and heavier. “Look, I get off shift at 02:00. Can you meet me at the phone box outside the NAAFI?” More gasps and a grunt which might have been a “yes”.

As a result when all the station personnel finally stood down and left it to the professionals, most of us were still ‘tooled up’. About eight that evening there was a knock on our back door (no phones in the MQs in those days – at least not at Abingdon) and the teenage daughter from three doors down said that she thought that there was somebody in their back garden. A couple of walkie-talkie calls up and down the line of MQs, and all doors opened, lights on and three of us outside ‘loaded for bear’, as the Yanks say. I was carrying my own personal 9mm Browning; four doors down my mate had a double barreled 12 Bore and across the back was a Flt Lt Para School Instructor (PJI – remember that acronym) who worked with unusual people who wore sandy coloured berets, and who came home at weekends with a small black case marked ‘H&K’, had out the contents by the way of an MP5. Sure enough there in the garden lights was a young bloke on his knees with his fly open and in ‘a compromising position’ looking through a ground floor window in the young neighbour’s MQ. Seeing the three of us all out in the lights he took off like a gazelle over the low fences between the back MQ gardens. As clearly he wasn’t a one-man Provo hit squad we all let him go without a shot fired, and all would have been well if round the corner at the end of Willow Tree Close had not come an RAF Regiment Land Rover, top down and set up for full counter-terrorist ops with every one of the Rock Apes armed to the teeth. All they saw was three blokes in uniform pointing an assortment of weapons at a running fugitive. Fortunately for said fugitive at that moment, probably startled by the Land Rover’s lights he caught his foot on the last low fence and went a-over-t right in front of the Regiment boys. Now don’t let them tell you that the human body cannot soil itself while running and jumping a fence. When last seen by us the miscreant was zip-tied and sitting on the tail gate of the Land Rover while all five of the Regiment blokes were in or standing on the front seats.

After he was taken back to the Guard Room and hosed down, it transpired that he was a young Corporal from the station Orderly Room who had a lot of trouble meeting and connecting with girls, and in his job he knew which MQ was occupied by either young wives with husbands away on detachment or by families with teen-age daughters. I believe that he was given a psychiatric discharge, and the potential for ‘The Gun Fight at Willow Tree Close’ never came up.

The next incident was even more stupid. Back then the station still had a manual telephone exchange manned by young WRAF airwomen. Shortly after the peeping tom incident (will they never learn?) there was a ‘heavy breather’ who used to phone up the station PBX in the wee small hours, and when the girl alone in the exchange answered, when into his heavy breathing and panting routine – though never a word was spoken. Needless to say this was really frightening the young girls, but their NCO, a more worldly-wise Corporal, took it in hand so to speak. She rostered herself on for the late shift and sure enough, the heavy breather came on line shortly after midnight a couple of days later. Instead of hanging up the Cpl responded “Ooh you do sound nice and exciting. Are you up for a good time?” She led him on a bit more as the breathing got heavier and heavier. “Look, I get off shift at 02:00. Can you meet me at the phone box outside the NAAFI?” More gasps and a grunt which might have been a “yes”.

The ‘gentleman’ concerned did indeed turn up at the NAAFI at 02:00, but was met not by the WRAF Corporal, but by her boyfriend, a Sergeant PJI and two of his mates. Apparently the heavy breather – yet again a bloke from the Station HQ – was very clumsy as he fell over and hit his face several times on the curb between the phone box and the Guard Room.

The third and final ‘incident’ could have been funny if it had not had such serious repercussions. There was an informal mixed function in the Officers’ Mess on a Saturday night, and Penny and I were attending. About ten o’clock in the evening the Station Duty Officer, a young UK MAMS bloke, came across to us. He knew I was ex-FEAF MAMS, and up to helping him out in a bit of agro: “Len. I think we’ve got a problem. There are three chaps here in rather disheveled clothing, two with bleeding knuckles and insisting that they are officers and want to have a drink”. He and I went across to the trio who were leaning against the bar, obviously having had a few drinks earlier in the night and rather the worse for wear. When again asked for identity they rather loudly insisted that they were Army Captains posted in to join the next Parachute School course starting the following Monday, and having just been commissioned from the ranks, had no Military Identity cards showing their new status. OK, we are in the Mess and there are ladies present, so the SDO and I quietly suggested that we go across the road to the RAF Guard Room (those of you familiar with Abingdon will remember that at the Main Gate the Officer’s Mess was immediately to the left and the Guard Room to the right). At this point the slightly more sober of the trio (and without bloody knuckles) grabbed his mates and, apologising for the “misunderstanding which would be sorted out in the morning” got his two chums out of the Mess.

Now you would think that that would have been the end of it. Oh no! About half an hour later the Abingdon Police were on the phone to the Guard Room, relayed to the SDO, asking if we’d seen three Army ORs who had been in an altercation in a pub in Abingdon town centre and were last seen climbing into a taxi and asking to be taken to “that Air Force place”. The SDO advised the Abingdon Police that the three were most probably back on the station but it was a little late to find them tonight and that the matter would indeed “be sorted out in the morning”.

Well, that was just the start of it. As luck (?) would have it I was SDO the following day (Sunday) and took over from a relieved young MAMS Flying Officer who was probably looking forward to something nice and simple - like a MAMS deployment to a major relief operation for a natural disaster overseas to get a bit of peace and quiet. I had barely got myself sorted out in the SDO’s Room in the Mess when the phone rang. “This is the (Yorkshire) West Riding Constabulary. Were you expecting Privates (X) and (Y) to arrive at your station this afternoon for a parachute course”? “Well I don’t know, but I’ll check and get back to you. Why?” “Well they are both in custody up here for indecent assault on a mentally disabled minor on a train south of York”. Sigh! “OK give me their names and I’ll inform the Para School”.

I contacted the Duty SNCO at the Para School and duly got a list of names of the intake that was supposed to be arriving over the weekend to start the course on the Monday. As the day progressed I received more and more phone calls from more and more civilian and military police forces round the country, advising that “Private (A)” or “Lance Corporal (B)” would not be arriving at Abingdon as he/they were in custody for various offences or misdemeanors including, in one case, crashing a car when ‘drunk and incapable’. By midnight when I finally got to bed in the SDO’s room I had crossed off almost half the names on the Para School’s roster of would-be Red Berets.

The following morning I handed over the whole mess to the Parachute School Adj with a verbal and written brief, went home for a bath and a change of uniform and headed back to the JATE hangar for just another day upside down under some new vehicle or other looking for somewhere to hang tie-down chains.

The third and final ‘incident’ could have been funny if it had not had such serious repercussions. There was an informal mixed function in the Officers’ Mess on a Saturday night, and Penny and I were attending. About ten o’clock in the evening the Station Duty Officer, a young UK MAMS bloke, came across to us. He knew I was ex-FEAF MAMS, and up to helping him out in a bit of agro: “Len. I think we’ve got a problem. There are three chaps here in rather disheveled clothing, two with bleeding knuckles and insisting that they are officers and want to have a drink”. He and I went across to the trio who were leaning against the bar, obviously having had a few drinks earlier in the night and rather the worse for wear. When again asked for identity they rather loudly insisted that they were Army Captains posted in to join the next Parachute School course starting the following Monday, and having just been commissioned from the ranks, had no Military Identity cards showing their new status. OK, we are in the Mess and there are ladies present, so the SDO and I quietly suggested that we go across the road to the RAF Guard Room (those of you familiar with Abingdon will remember that at the Main Gate the Officer’s Mess was immediately to the left and the Guard Room to the right). At this point the slightly more sober of the trio (and without bloody knuckles) grabbed his mates and, apologising for the “misunderstanding which would be sorted out in the morning” got his two chums out of the Mess.

Now you would think that that would have been the end of it. Oh no! About half an hour later the Abingdon Police were on the phone to the Guard Room, relayed to the SDO, asking if we’d seen three Army ORs who had been in an altercation in a pub in Abingdon town centre and were last seen climbing into a taxi and asking to be taken to “that Air Force place”. The SDO advised the Abingdon Police that the three were most probably back on the station but it was a little late to find them tonight and that the matter would indeed “be sorted out in the morning”.

Well, that was just the start of it. As luck (?) would have it I was SDO the following day (Sunday) and took over from a relieved young MAMS Flying Officer who was probably looking forward to something nice and simple - like a MAMS deployment to a major relief operation for a natural disaster overseas to get a bit of peace and quiet. I had barely got myself sorted out in the SDO’s Room in the Mess when the phone rang. “This is the (Yorkshire) West Riding Constabulary. Were you expecting Privates (X) and (Y) to arrive at your station this afternoon for a parachute course”? “Well I don’t know, but I’ll check and get back to you. Why?” “Well they are both in custody up here for indecent assault on a mentally disabled minor on a train south of York”. Sigh! “OK give me their names and I’ll inform the Para School”.

I contacted the Duty SNCO at the Para School and duly got a list of names of the intake that was supposed to be arriving over the weekend to start the course on the Monday. As the day progressed I received more and more phone calls from more and more civilian and military police forces round the country, advising that “Private (A)” or “Lance Corporal (B)” would not be arriving at Abingdon as he/they were in custody for various offences or misdemeanors including, in one case, crashing a car when ‘drunk and incapable’. By midnight when I finally got to bed in the SDO’s room I had crossed off almost half the names on the Para School’s roster of would-be Red Berets.

The following morning I handed over the whole mess to the Parachute School Adj with a verbal and written brief, went home for a bath and a change of uniform and headed back to the JATE hangar for just another day upside down under some new vehicle or other looking for somewhere to hang tie-down chains.

Just before lunch I got a call from my boss to tell me that our Brigadier had in turn received a call that the CO of the Parachute School wanted to see me in his office. Quick change out of my grotty old climb-under-vehicles flying suit, grab the Ferret ‘staff car’ and down to the Para School HQ. Quick word with the Adj and a raised questioning eye-brow about our de-brief earlier that morning. “The Colonel wants to see you personally” Oh Sierra Hotel India Tango what did I get wrong? Enter Colonel’s office, smart salute and remain at attention, waiting for the storm. “Ah Flight Lieutenant Bowen, I gather you had an interesting day yesterday.” “Yes Sir; it had its moments”. “Look Flight Lieutenant, on behalf of the Parachute Regiment I most sincerely apologise for the trouble you and the Station have been put to. I and my Regiment are ashamed of the whole incident, and I can advise you informally that Number (X) of 197(Y) Parachute Course has been cancelled because there are now insufficient numbers to run the course”. Wow! “Oh and I will be talking to you Commandant about how well you handled the whole thing. Now please sit down and have a cup of coffee” Wow Squared! Actually our Brigadier never formally mentioned the matter, but the next time he saw me in the Mess he just quietly said “Well done Len. Nicely handled”.

At this point I should introduce ‘The Brig’. He was a top bloke. Seldom saw him down on the hangar floor, but when you did he was always interested in the task on hand, and not averse to climbing under the latest ‘customer’ to see how the job was going. He had a beautiful old black Labrador which followed him everywhere, and stayed in the Mess with him. He – the Brig – was married, but lived in the Mess during the week. Every evening at about 10 o’clock he would come into the Mess bar with his dog (OK, I know that the Mess Rules were ‘No Dogs in Public Rooms’ but are you going to tell a One Star with three rows of gongs that his lab couldn’t come into the bar – especially as most of us were dog lovers anyway?) and ordered “A double Scotch for myself and a packet of plain crisps for the dog”. Every second day “…oh and a bottle to go, please.” That was a full bottle of Scotch. Never ever saw the Brig even remotely worse for wear, even at major Mess functions, so assumed that the bottle(s) at Mess prices went home at weekends?

JATE – at least the Air Landing Wing – was at that time full of characters. We had a USAF Exchange Officer, Major George Bussing. George was from an ‘Old Money’ Boston family, and out-Brit’ed the Brits. He drove an R Type Bentley and with our immediate boss Squadron Leader Bill, loved country point-to-point races. Bill was an ace on the gee-gees. Not the big race days like Ascot or Epsom, but the little county and country race meets. A canny Scot, he knew many of the runners round the country, their form and where they were stabled, and he would say “Aye weeell if So-and-So thinks it’s worth bringing Such-and-Such all the way from Norfolk to Oxfordshire for a point-to-point he/she might be worth a pound or two”, and he was seldom wrong. Unfortunately back in those days still recovering financially from the Malta short tour it was not often that I could afford to follow his tips.

If I’ve given the impression that Major George was an Ivy League poser with his Bentley and his Harris Tweed jackets; wrong. George was a highly decorated USAF officer with two tours in Vietnam. When in uniform around Abingdon he only had four medal ribbons up, but once every three months when he had to go across to Upper Heyford to report to his nearest senior USAF officer, and incidentally stock up on PX goodies, he had four rows of decorations on his uniform. One night in the Mess when we got to know George and his lovely wife better, we asked him about the ribbons. “Well”, he said “Round you Brits who only ever wear gallantry medals or serious in-country time ribbons, I only wear the four I really think I earned at the sharp end. The rest are time-served colour”. That sort of man you respect.

In between all this we actually got some joint air transport development work done – that was when we were not playing James Bond. Like when John (surname redacted but he was also a brilliant nature photographer) one of our civilian engineers and I went to the Paris Air Show to try to get some gen on the Russian transport aircraft of the day.

At this point I should introduce ‘The Brig’. He was a top bloke. Seldom saw him down on the hangar floor, but when you did he was always interested in the task on hand, and not averse to climbing under the latest ‘customer’ to see how the job was going. He had a beautiful old black Labrador which followed him everywhere, and stayed in the Mess with him. He – the Brig – was married, but lived in the Mess during the week. Every evening at about 10 o’clock he would come into the Mess bar with his dog (OK, I know that the Mess Rules were ‘No Dogs in Public Rooms’ but are you going to tell a One Star with three rows of gongs that his lab couldn’t come into the bar – especially as most of us were dog lovers anyway?) and ordered “A double Scotch for myself and a packet of plain crisps for the dog”. Every second day “…oh and a bottle to go, please.” That was a full bottle of Scotch. Never ever saw the Brig even remotely worse for wear, even at major Mess functions, so assumed that the bottle(s) at Mess prices went home at weekends?

JATE – at least the Air Landing Wing – was at that time full of characters. We had a USAF Exchange Officer, Major George Bussing. George was from an ‘Old Money’ Boston family, and out-Brit’ed the Brits. He drove an R Type Bentley and with our immediate boss Squadron Leader Bill, loved country point-to-point races. Bill was an ace on the gee-gees. Not the big race days like Ascot or Epsom, but the little county and country race meets. A canny Scot, he knew many of the runners round the country, their form and where they were stabled, and he would say “Aye weeell if So-and-So thinks it’s worth bringing Such-and-Such all the way from Norfolk to Oxfordshire for a point-to-point he/she might be worth a pound or two”, and he was seldom wrong. Unfortunately back in those days still recovering financially from the Malta short tour it was not often that I could afford to follow his tips.

If I’ve given the impression that Major George was an Ivy League poser with his Bentley and his Harris Tweed jackets; wrong. George was a highly decorated USAF officer with two tours in Vietnam. When in uniform around Abingdon he only had four medal ribbons up, but once every three months when he had to go across to Upper Heyford to report to his nearest senior USAF officer, and incidentally stock up on PX goodies, he had four rows of decorations on his uniform. One night in the Mess when we got to know George and his lovely wife better, we asked him about the ribbons. “Well”, he said “Round you Brits who only ever wear gallantry medals or serious in-country time ribbons, I only wear the four I really think I earned at the sharp end. The rest are time-served colour”. That sort of man you respect.

In between all this we actually got some joint air transport development work done – that was when we were not playing James Bond. Like when John (surname redacted but he was also a brilliant nature photographer) one of our civilian engineers and I went to the Paris Air Show to try to get some gen on the Russian transport aircraft of the day.

We had almost a week living on our allowances in a delightful small hotel, eating fine French food, and wasting our time at all the public days of the Salon international de l'aéronautique et de l'espace de Paris-Le Bourget, Salon du Bourget – well you did ask. Not one of the Russian transport aircraft was anywhere near the public enclosures, so we had little hope of getting a good look at one. Imagine, then, our surprise when we arrived the day after the Public Days – to find an An 22 COCK being loaded right in front of us and no barriers in place. John and I were dressed in scruff order, and amazingly enough got right up to the aircraft and started to help the Russian crew get their gear aboard. We’d been at it for about an hour, with John getting good photos of their tie-down gear and the overhead gantry (f*c* off Boris, the Beverley had this first!) when I cocked up. The Russian loading team (RUSKI MAMSKI?) were happy with all the help from the unskilled ‘French’ labour that they could get, but unfortunately, as we were moving one of their small aerobatic aircraft up the ramp it started to slip back and, without thinking I instinctively slammed a near-by chock behind the wheel, chucked a chain round the bottom of the landing gear and locked it off to the floor like I’d seen the Russian boys do. I got a raised eyebrow from a bloke I assumed was the RUSKI MAMSKI Team Leader, like “OK, mate, takes one to know one. We now know that you know that we know that you know what you are doing in the movements business, but we still need all the help we can get to get this big bugger loaded and off chocks on time”…however just then a Commissar in a smart clean uniform with a bloody big flat cap saw the exchange, and John and I were kicked off the aircraft in very short order. Got a shrug from the MAMSKI boss, like “Oh well Comrade, we’ll just get on with it without any outside professional help” and off we went back to the hotel and a glass or three of vin ordinaire … and some beaut photos of all their loading and lashing gear!

My last few months at Abingdon were tinged with sadness, not just because we were leaving a station where we were supremely happy, with a new son, and with the Black Horse pub just round the back of the airfield (another story for another time), but because my last task at Air Land Wing was to help calculate what British military equipment would no longer be air-portable by RAF-Air when the Belfast fleet was sold off. The answer was, of course, most if not all of the Royal Engineers plant, most of the AFVs and armour and a lot more besides. Inevitably within a few months HeavyLift UK had bought up the Belslows and for many years until the arrival of the C17 and the A400, it was costing MoD big big money for them or the Yank C5s or even later the Russian Antanovs, to move what we had previously been able to move ‘in house’.

My last few months at Abingdon were tinged with sadness, not just because we were leaving a station where we were supremely happy, with a new son, and with the Black Horse pub just round the back of the airfield (another story for another time), but because my last task at Air Land Wing was to help calculate what British military equipment would no longer be air-portable by RAF-Air when the Belfast fleet was sold off. The answer was, of course, most if not all of the Royal Engineers plant, most of the AFVs and armour and a lot more besides. Inevitably within a few months HeavyLift UK had bought up the Belslows and for many years until the arrival of the C17 and the A400, it was costing MoD big big money for them or the Yank C5s or even later the Russian Antanovs, to move what we had previously been able to move ‘in house’.

In our case two and a half years later to move on to Australia, the RAAF, and another thirty three years in and out of the movements game, one way or another. But that REALLY is another story for another time.

Len Bowen

23 Apr 2018.

Len Bowen

23 Apr 2018.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

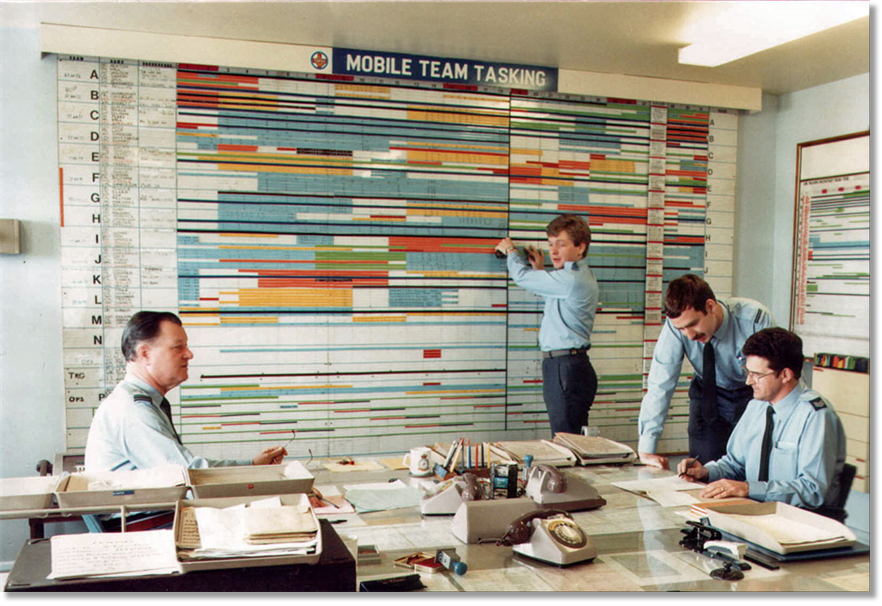

We left Abingdon in August 1975 for Headquarters Support Command Andover. Another MQ, with a railway at the bottom of the garden, lovely fruit trees - and a different sort of ‘movements’, with my new job as MOV(MT) 1B, the Tasking Officer for the three RAF specialist Road Transport Squadrons.

Penny and I had loved our time at Abingdon – in my case back at Abingdon - the REAL home of RAF Air Movements, but it was time to move on. And how!

Penny and I had loved our time at Abingdon – in my case back at Abingdon - the REAL home of RAF Air Movements, but it was time to move on. And how!

RAAF Receives 10th and Final C-27J Spartan Transport Aircraft

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has received its 10th and final Leonardo C-27J Spartan twin-turboprop, tactical transport aircraft.

Minister for Defence Marise Payne and Minister for Defence Industry Christopher Pyne announced on 18 April that the final C-27J had been “welcomed into service” in a ceremony held at RAAF Base Richmond, adding that the move marks the upgrade completion of the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) fleet of air-mobility platforms. “The Spartan provides flexibility to Defence operations, allowing us to land at airfields that are smaller or unsuitable for our much larger transport aircraft like the C-130J Hercules and C-17A Globemaster,” said Payne.

In service with the RAAF’s No 35 Squadron, the C-27Js are intended to provide a battlefield airlift capability for the ADF as well as to supplement the existing Australian Army and Royal Australian Navy’s fleet of helicopters in the airlift role. Initial operating capability for the platform was announced in late 2016, with final operating capability scheduled to be declared in late 2019. Payne also announced that the C-27Js, which are currently operated from RAAF Base Richmond, are set to relocate to RAAF Base Amberley in early 2019. “The relocation to Amberley will allow No 35 Squadron to work from facilities purpose-built for the Spartan, and to be more responsive when deploying across Australia and into the Asia Pacific,” said Payne.

In November 2017 the Australian Department of Defence (DoD) announced that it had awarded an AUD200 million (USD155.5 million) contract to Northrop Grumman that covers through-life support (TLS) services for the RAAF’s C-27J fleet.

Jane's 360

Minister for Defence Marise Payne and Minister for Defence Industry Christopher Pyne announced on 18 April that the final C-27J had been “welcomed into service” in a ceremony held at RAAF Base Richmond, adding that the move marks the upgrade completion of the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) fleet of air-mobility platforms. “The Spartan provides flexibility to Defence operations, allowing us to land at airfields that are smaller or unsuitable for our much larger transport aircraft like the C-130J Hercules and C-17A Globemaster,” said Payne.

In service with the RAAF’s No 35 Squadron, the C-27Js are intended to provide a battlefield airlift capability for the ADF as well as to supplement the existing Australian Army and Royal Australian Navy’s fleet of helicopters in the airlift role. Initial operating capability for the platform was announced in late 2016, with final operating capability scheduled to be declared in late 2019. Payne also announced that the C-27Js, which are currently operated from RAAF Base Richmond, are set to relocate to RAAF Base Amberley in early 2019. “The relocation to Amberley will allow No 35 Squadron to work from facilities purpose-built for the Spartan, and to be more responsive when deploying across Australia and into the Asia Pacific,” said Payne.

In November 2017 the Australian Department of Defence (DoD) announced that it had awarded an AUD200 million (USD155.5 million) contract to Northrop Grumman that covers through-life support (TLS) services for the RAAF’s C-27J fleet.

Jane's 360

A RAAF C-27J Spartan lands on the grass airstrip at RAAF Base Richmond at the completion of a mission demonstration during a ceremony to announce completed delivery of No. 35 Squadron's fleet of ten C-27J Spartans. Announced as Air Force's new battlefield airlifter in May 2012, the first aircraft arrived in Australia in June 2015, with the tenth aircraft arriving in early April 2018.

Royal Australian Air Force

Royal Australian Air Force

Members of No. 2 Commando Regiment watch a RAAF C-27J Spartan taxi on a grass airstrip at RAAF Base Richmond, during a ceremony to announce completed delivery of the fleet of ten Spartans. In Defence service, the Spartan will provide a flexible and versatile airlifter into frontline airfields that are unsuitable for larger transport aircraft.

Royal Australian Air Force

Royal Australian Air Force

A marshaller guides a RAAF C-27J Spartan into parking position on a grass airstrip at RAAF Base Richmond. The Spartan fleet will relocate to purpose-built faciilities at RAAF Base Amberley by early 2019.

Royal Australian Air Force

Royal Australian Air Force

Air Force personnel, Family members of No. 35 Squadron, and industry guests watch as a C-27J Spartan parks at a ceremony to announce the completed delivery of the Spartan fleet. In the past 12 months, the Spartans have supported elections in Papua New Guinea, as well as participated in exercises in New Zealand, Guam, and New Caledonia.

Royal Australian Air Force

Royal Australian Air Force

Deputy Chief of Air Force, Air Vice-Marshal Gavin Turnbull, addresses the crowd at RAAF Base Richmond during a ceremony to announce completed delivery of the Spartan fleet. In Air Force service, the Spartan will provide a wider range of options for how the Australian Army (and other Government agencies) can be supported in austere environments.

Royal Australian Air Force

Royal Australian Air Force

A static display of C-27J Spartans during a ceremony to announce the completed delivery of the Spartan fleet. The aircraft can be configured for a variety of missions including airdrop, aeromedical evacuation, and carrying vehicles and personnel to austere airfields.

Royal Australian Air Force

Royal Australian Air Force

The Air Ministry supplied my one-way airline ticket for a flight to Australia. It was bought from BOAC who had a tie-up arrangement with Qantas who had no handling facilities along the route until we reached Perth.

Though drinks were served on the flight, all meals were served on the ground. BOAC had 'Speedbird' houses at each refuelling stop where one could have a wash and brush up, followed by a slap-up meal washed down with free beer. There was none of the inevitable hassle that one experiences at today's international airports. Today, flights give top speed but don't give pleasure. In days long gone by there was no queuing and no security problems - hence flying was so much more enjoyable.

RAF charge sheets were listed on Form 252, so it was easy to remember that number was also the price of BOAC's one-way ticket. Compare the value of £252 in 1956 with today's prices - it is calculated at a staggering £5978. If the math is wrong - blame the Internet.

Though drinks were served on the flight, all meals were served on the ground. BOAC had 'Speedbird' houses at each refuelling stop where one could have a wash and brush up, followed by a slap-up meal washed down with free beer. There was none of the inevitable hassle that one experiences at today's international airports. Today, flights give top speed but don't give pleasure. In days long gone by there was no queuing and no security problems - hence flying was so much more enjoyable.

RAF charge sheets were listed on Form 252, so it was easy to remember that number was also the price of BOAC's one-way ticket. Compare the value of £252 in 1956 with today's prices - it is calculated at a staggering £5978. If the math is wrong - blame the Internet.

From: Sam Mold, Brighton & Hove

Subject: Times gone by

Hi Tony,

Last month's newspapers published an account of an Australian Qantas 'Dreamliner' (Boeing 787) flying non-stop from Oz to UK (Perth to London) in 17 hours. Wow! Of course, I could not let that go by without comparing this to my own 1956 four-day scheduled flight to Sydney, courtesy of a Qantas Airlines L-1049 Super Constellation. The image on the following page shows a similar flight route to the one I took in 1956. The two main differences were at the start and end of the journey. The first stop on this long flight to Oz was at Rome (not Tripoli), and the other deviation was after an overnight stay in Singapore, we landed in Indonesia (Jarkata) before continuing to Perth where the Oz Immigration Office was situated and my passport was stamped to confirm my arrival. Some 15 months later I flew out of RAAF Edinburgh Field (near Adelaide) to return home on an original RAF Comet C2. As the RAAF base did not have an Ozzie Immigration Office, means my passport confirms I have never left Australia. Can I now claim citizenship?

Subject: Times gone by

Hi Tony,

Last month's newspapers published an account of an Australian Qantas 'Dreamliner' (Boeing 787) flying non-stop from Oz to UK (Perth to London) in 17 hours. Wow! Of course, I could not let that go by without comparing this to my own 1956 four-day scheduled flight to Sydney, courtesy of a Qantas Airlines L-1049 Super Constellation. The image on the following page shows a similar flight route to the one I took in 1956. The two main differences were at the start and end of the journey. The first stop on this long flight to Oz was at Rome (not Tripoli), and the other deviation was after an overnight stay in Singapore, we landed in Indonesia (Jarkata) before continuing to Perth where the Oz Immigration Office was situated and my passport was stamped to confirm my arrival. Some 15 months later I flew out of RAAF Edinburgh Field (near Adelaide) to return home on an original RAF Comet C2. As the RAAF base did not have an Ozzie Immigration Office, means my passport confirms I have never left Australia. Can I now claim citizenship?

Turning back to my 1956 posting to Australia, it was the first time I had to apply for a passport, and since then, I have obtained five more.

Originally, it was arranged that the flight to Oz was to be by a civilian chartered York a/c that would have flown out via refuelling stops at military air bases along the route. Provided such bases were used, RAF and charted flights could fly all the way to Iwakuni in Japan (thence to Korea by Sunderland flying boats operating out of RAF Seletar in Singapore) - all without the need for a passport.

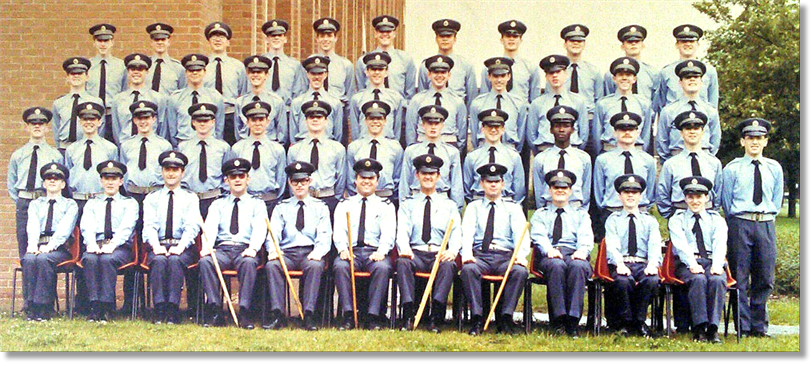

In 1956, a posting came through to join an RAF Air Task Group (ATG) that had been formed at RAF Weston Zoyland (in Somerset) to support the atomic bomb trials to be held at Maralinga in the South Australian desert.

The designated name for these tests was Operation 'Buffalo'.

Civilian York aircraft were chartered to transport the ATG personnel to Australia, but when a 'Scottish Airlines' York crashed on take-off from RAF Luqa in Malta, they were all grounded until the cause of the crash could be established. That's when panic set in.

Met officers had already planned the time when it would be safe to conduct these atomic tests to ensure that any nuclear fall out would not occur over populated areas such as Alice Springs, Perth and Adelaide, so it was essential to stick to the plans already prepared.

Talk about government top priorities. No obstructions were allowed to hinder the government's desire to become a member of the Nuclear Club alongside the USA and the Soviet Union One morning the Task Group were lined up to list their personnel details to add to passport photos once taken. A motorcycle dispatch rider rushed them to London, and I still find it hard to believe that we all possessed a passport later that day. That's what 'pulling all the stops out' means.

Originally, it was arranged that the flight to Oz was to be by a civilian chartered York a/c that would have flown out via refuelling stops at military air bases along the route. Provided such bases were used, RAF and charted flights could fly all the way to Iwakuni in Japan (thence to Korea by Sunderland flying boats operating out of RAF Seletar in Singapore) - all without the need for a passport.

In 1956, a posting came through to join an RAF Air Task Group (ATG) that had been formed at RAF Weston Zoyland (in Somerset) to support the atomic bomb trials to be held at Maralinga in the South Australian desert.

The designated name for these tests was Operation 'Buffalo'.

Civilian York aircraft were chartered to transport the ATG personnel to Australia, but when a 'Scottish Airlines' York crashed on take-off from RAF Luqa in Malta, they were all grounded until the cause of the crash could be established. That's when panic set in.

Met officers had already planned the time when it would be safe to conduct these atomic tests to ensure that any nuclear fall out would not occur over populated areas such as Alice Springs, Perth and Adelaide, so it was essential to stick to the plans already prepared.

Talk about government top priorities. No obstructions were allowed to hinder the government's desire to become a member of the Nuclear Club alongside the USA and the Soviet Union One morning the Task Group were lined up to list their personnel details to add to passport photos once taken. A motorcycle dispatch rider rushed them to London, and I still find it hard to believe that we all possessed a passport later that day. That's what 'pulling all the stops out' means.

With no military air transport or charter flights available, the Air Ministry had no alternative than to quickly arrange for ATG personnel to be flown out by civilian airlines. The first ATG batch flew the westwards route to Australia with Pan American Airlines flying Boeing Stratocruisers. I was with the second batch taking the eastern Empire route aboard a Qantas L-1049 Super Constellation that landed me in Sydney on 9th May 1956. Transferring to a Trans Australian Airlines Vickers Viscount flying to Adelaide, I reached my destination.

My apologies for the ramblings of a cantankerous old codger that started out as a 'then' and 'now' comparison of flights, but along the line I got carried away - so please make allowances for my addled brain. The moral to this comment is: never reach your 88th year, for Mother Nature has a massive armoury containing every ailment known to mankind, and she doesn't discriminate when it comes to doling them out. However, one good thing in her favour; she normally lets you enjoy wild oats before making serious health attacks. At least, after a debauched lifestyle, I'm still sticking by my mantra: I will survive!

And Tony, the road to survival is what your OBA members wish you to travel down so that you can keep up the grand work you do on behalf of your members. I'm sure every one of us truly appreciates the efforts you put into keeping colleagues in touch, along with the news and information you publish in your very successful newsletter.

Long may your endeavours continue.

With my very best wishes, ex-AMDU/MAMS member,

SAM.

My apologies for the ramblings of a cantankerous old codger that started out as a 'then' and 'now' comparison of flights, but along the line I got carried away - so please make allowances for my addled brain. The moral to this comment is: never reach your 88th year, for Mother Nature has a massive armoury containing every ailment known to mankind, and she doesn't discriminate when it comes to doling them out. However, one good thing in her favour; she normally lets you enjoy wild oats before making serious health attacks. At least, after a debauched lifestyle, I'm still sticking by my mantra: I will survive!

And Tony, the road to survival is what your OBA members wish you to travel down so that you can keep up the grand work you do on behalf of your members. I'm sure every one of us truly appreciates the efforts you put into keeping colleagues in touch, along with the news and information you publish in your very successful newsletter.

Long may your endeavours continue.

With my very best wishes, ex-AMDU/MAMS member,

SAM.

From: John Holloway, Shrewsbury

Subject: Checking up