Subject: The Baby Airlift from Saigon

Thanks, Tony for another great newsletter.

I found the first article (Operation Babylift), in the last newsletter very interesting because I was there also, just after the C5A Galaxy crashed in Saigon. We were on a training mission with 426(T) Sqn out of Trenton. I had two students with me; Jim Abbott and the late Wiff Burns. Unfortunately, I was only permitted to take one with me from Hong Kong and that happened to be Wiff.

When we arrived in Saigon, there was one, maybe two, RAAF C130s on the ground and when we were ready to leave, they had already departed. We had 74 + 1 babies on board, destined to Hong Kong where they would transfer via Canadian Pacific Airlines to Vancouver and beyond. I was concerned about the baskets of supplies that came on board, so I searched them, much to the dismay of some others. However, we didn't know at that time what caused the Galaxy to crash, so I was not taking any chances.

Anyway, off we went to Hong Kong and continued on our training mission the next day. It ended up being a good trip with a lot of great memories. Wiff had a copy of the passenger manifest out of Saigon and I recall just about all of the names on it were “Nguyen”, being the most common surname in Vietnam.

Best regards,

Fred

The move comes amid growing concerns over airlift capacity and long-term fleet resilience.

In a written response to Conservative MP Ben Obese-Jecty, Minister of State for Defence Maria Eagle stated that “all capability requirements, including those for tactical airlift, are being considered as part of the Strategic Defence Review process.”

Currently, the Royal Air Force operates 22 A400M aircraft, which serve as the backbone of the UK’s tactical and strategic air mobility. The A400M is capable of transporting up to 37 tons of cargo or 116 fully equipped personnel. With a top speed of 780 km/h and a range of up to 8,900 kilometers, the aircraft offers global reach and operational flexibility, including the ability to take off and land on unpaved runways and perform low-level tactical flight.

Officials have not yet confirmed a timeline or funding allocation, but internal discussions have pointed to the possibility of acquiring up to six more units by 2030. However, such a move would require navigating tight fiscal constraints, with defense planners weighing the procurement against broader budgetary pressures.

The A400M also supports aerial refueling, medical evacuation, and rapid deployment of troops and equipment. It replaced the UK’s fleet of 14 C-130J Super Hercules aircraft, which were officially retired on June 30, 2023.

Beyond the A400M, the Royal Air Force also operates eight C-17 Globemaster III strategic airlifters. With the C-17 line no longer in production, allied nations have limited options for large military transport aircraft, placing greater emphasis on existing fleets.

defence-blog.com

In a global context where climate change poses a threat as urgent as armed conflicts, wildfires have increased in both frequency and intensity. This growing threat demands enhanced response capabilities, and platforms like the C-130H Hercules have emerged as one of the most effective tools to meet these challenges.

The C-130H aircraft, as used by Coulson, stand out for their capacity to carry between 4,000 and 5,000 gallons (15,000 to 19,000 liters) of fire retardant per drop, allowing them to cover vast areas in a single pass. Their extended range enables long-duration missions, and they are capable of taking off and landing on short or unprepared runways—a key feature for operations in remote or hard-to-access regions. Moreover, their performance has far surpassed that of helicopters and smaller aircraft, making them a strategic asset in large-scale fires like those that frequently affect California, Australia, and the Amazon.

In the words of Britton Coulson, President and COO of the company: “This acquisition marks another significant milestone for Coulson Aviation and the future of aerial firefighting. These aircraft continue to enhance our ability to respond quickly and effectively to wildfires around the globe—saving lives, protecting communities, and preserving vital natural and economic resources. With the addition of these four C-130Hs to our fleet, we reaffirm our commitment to leading the industry with the world’s most capable and highest-performing large airtankers.”

The decision to expand the fleet also comes in response to the gradual aging of many aircraft traditionally used in firefighting missions, such as the P-3 Orion, DC-10, and the Boeing 747 Supertanker—the latter retired in 2019—which are reaching the end of their operational lives. The addition of the retired New Zealand C-130Hs will allow Coulson to replace outdated platforms with more robust, versatile, and easily modifiable aircraft, especially considering that the company already operates other Hercules variants like the C-130Q/L-382 (civilian versions of the Hercules), adapted for aerial firefighting missions using systems such as MAFFS II and RADS-XXL.

The aircraft, which were replaced in the RNZAF by the more modern C-130J-30 Super Hercules, will be transferred to Coulson’s base in Thermal, California, where they will undergo a complete conversion and modernization process to prepare them for their new role. Notably, Coulson is one of the few companies worldwide operating specially modified Hercules aircraft for firefighting duties, with a strong reputation for both initial attack and extended support operations.

In the words of Britton Coulson: “We’ve all seen the trend of increasingly intense and destructive fires in recent years, beginning with Lahaina (Maui) in 2023, followed by Malibu (California) in 2024/2025. On days marked by extreme fire behavior, it’s the large assets like the C-130 and CH-47 that can truly make the difference.”

zona.militar.com

Subject: Tipping a C130

Hi Tony,

Your recent email mentioned 'accidentally' tipping a C130 in Peru. This later became an accepted practice and, as far as I know, Juliet Team became the first UK MAMS team to employ it; legally that is!

Qualification: These memories are over 50 years old, so there will be some inaccuracies.

The Team: Bob Turner, Hugh Curran, Martin Gledhill, myself and two others.

The Task: Load a C130 with an Army Lynx helicopter at Brize Norton and offload it at Ottawa for cold weather trials then on to Calgary to pick up a Beaver from Exercise Medicine Hat and return to UK.

Briefing: The Team deployed to Brize where we underwent training with JATE on the technique for tipping the C130 so as to load the Lynx. It was explained that there were 3 conditions where this could be employed and that it involved using the ramp as a lift to provide a straight, flat floor. The conditions were:

1) When, otherwise, the load would hit the aircraft roof when winched up the ramp.

2) When an axle weight exceeded the chine cap max l load of 25,000 lbs.

3) When a tracked vehicle of over a certain weight was loaded.

The load plan included all sorts of warnings and restrictions. Some that I recall were:

1) The wind speed limit was 3 knots otherwise, with the nose wheel off the ground, the tail fin would act as a sail and swing the whole aircraft around.

2) To obviate this risk a team member had to sit in the cockpit and apply the brakes during the onload and offload.

Execution: Duly trained by JATE, the Lynx was loaded without issues and we headed off to Ottawa and enjoyed a night stop at Gander and a few beers at the Albatross.

On arrival at Ottawa, the aircraft was parked in a suitable spot out of the breeze and the offload began in front of numerous watchers. As word spread, quite an audience came to see the sight. Chocks were removed, a team member sat in the cockpit riding the brakes and the ramp was lowered to be level with the main floor. The Lynx was pushed back onto the until the aircraft tipped - ever so gently. It was at this point that I decided to demonstrate how moments of inertia around a fixed centre of gravity worked and walked from the ramp to the front of the aircraft. Sure enough, the aircraft settled onto its nose wheel. I then stepped out the crew door and the nose wheel rose into the air again.

A figure in an RAF Wing Commander uniform rushed out of a building, grabbed me and started foaming at the mouth,

"What the #### do you think you are doing you stupid ####?"

"But Sir", I tried to respond before being subjected to another stream of invective.

Eventually calm was restored and the Wing Commander - a visitor from Group - calmed down with the full explanation of what was going on.

I dusted myself down, completed the offload and the rest of the task was completed without incident.

The tipping technique was not much used but, by coincidence, I had to use it again a couple of times when I was SAMO at RAF Gutersloh during the Gulf War deployment.

Best regards

Ron

Subject: Survival Courses

Hi Tony,

Nothing to offer in terms of survival training daring and excitement while on MAMS; just a couple of recalls under this general heading. Including, after an evening with several bevies in the RAF Changi Temple Hill bar with one of the Jungle Survival instructors, I found myself in the School’s hangar jumping off a very high tower attached by string to a crude sort of propeller machine which had the effect of slowing down, in theory, the effects of gravity while practising undoing your parachute harness in mid-fall. And, then jumping out of said harness, shortly before arriving on a large mattress which represented the sea. This bizarre ritual then allowed me to join said drinking companion that same afternoon and jumping out of a Beverley chugging over the Malacca Straight, the famous ‘Changi Splash’.

The other vague recall was camping in snow on the lower slopes of the Troodos Mountains in Cyprus as part of our year one of three Cranwell Flight Cadet training. This concluded with a three-day trek, as simulated shot down ‘crews’ of three, across said mountain range from the South coast somewhere near Limassol to a pick-up point on the North West coast at Morphou Bay. This trek across the Troodos range was enlivened by being sought by RAF Regiment and the British Army with helicopters and Landrovers. If caught , as we were once, you were bundled into the back of a Landrover and taken back 20 miles. A sort of sadistic form of snakes and ladders. Very little in terms of rations, which meant scrumping fruit, and occasionally seeking help in local villagers. They were very generous on learning the we were ‘Escaping from British Army Prison’. On the last night, nearing journey’s end, it was raining very, and I mean very, heavily, so we resorted to blagging a night in the Police cells in Morphou town. The following morning a very nice policeman helped us by showing through the orange groves to our pick-up point. Interestingly, apparently a couple of the ‘crews’ really got into the role-playing spirit of the exercise by stealing a local bus which they used for much of the way!

Apparently, this was the only time this Cranwell exercise was ever held in Cyprus.

Stay safe, have fun

David Powell F Team Abingdon 1967-69

Subject: Survival Courses

Hi Tony,

Yes, I recall doing that self-same course at Mount Batten, in 1982. It was the dying days of the RAF Marine Branch, and one of their few remaining roles was operating the vessels at Mount Batten, which was also home to HQ 18 Group at the time.

I remember the course well, for 3 reasons:

1. I was a spare Pilot Officer on UKMAMS at the time, and was sent on the course with another team. Their Team Leader was an officer who shall remain nameless but of whom the stories of his mis-doings were legion, and he lived up to his reputation from minute one of the course. After a few days, the Station Warrant Officer (SWO) came looking for me and asked me to “Sort out the scruffy airman who was causing problems wherever he went”. When I explained that there was little I could do, as said ‘scruffy airman’ was actually an officer superior in rank to me (a Flying Officer) the SWO’s eyes nearly popped out of his head before his brow then set in a steely frown, he parked his swagger stick under his arm in a forceful manner and with a muttered, “Right then.” marched off in a very purposeful fashion.

2. It was bloody freezing.

3. There were two young Royal Marines on the course - like me, just filling in time as supernumerary members of their unit - who, when the instructors threw the dinghy in upside down, jumped in and righted it in about 7 seconds flat, much to our delight and said instructors chagrin!

Happy days!

Keep up the good work,

Steve

How Prestwick Became Canada’s Airlift Hub in Europe

In late March 2022, as the international community responded to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Canada stood up a Tactical Airlift Detachment at Prestwick. Initially consisting of two RCAF CC-130J Hercules transport aircraft and their crews, the detachment began operating out of the airport to move urgent supplies and military aid into Europe. Within months, the mission expanded. By September 2022, Canada added a third Hercules and increased its deployed personnel to roughly 55–60 Canadian Armed Forces members. The detachment was re-designated Air Task Force – Prestwick (ATF-P) to reflect its broadened scope and permanence. The task force has since evolved into a full-fledged Air Mobility Hub in Europe, handling everything from aircraft maintenance and cargo operations to crew administration. The team regularly supports not only the three Hercules aircraft but also larger RCAF CC-177 Globemaster III cargo jets rotating through the airport.

Air Task Force

Prestwick plays a central role in Canada’s ongoing support to Ukraine. Since spring 2022, its aircraft have delivered vast quantities of military and humanitarian cargo—everything from ammunition and protective gear to medical supplies—into Europe for onward delivery to Ukrainian forces.

By the autumn of 2022, the Canadian aircraft based at Prestwick had transported over 4 million pounds of Ukraine-bound cargo. By the end of 2023, that figure had surpassed 20 million pounds, marking a remarkable contribution to NATO’s logistics effort.

These deliveries form a core part of Canada’s broader commitment to Ukraine and demonstrate how Prestwick has become an essential lifeline between North America and the European theatre.

Beyond Ukraine

While supporting Ukraine remains a priority, ATF-P also underpins several other Canadian military operations worldwide. The detachment at Prestwick serves as a launchpad for:

⦁ Operation REASSURANCE – Canada’s commitment to NATO’s enhanced forward presence in Eastern Europe, particularly in Latvia;

⦁ Operation IMPACT – missions in the Middle East;

⦁ Operation PRESENCE – deployments supporting UN peacekeeping in Africa;

⦁ Open Skies Treaty observation flights.

Thanks to its ideal location and established facilities, Prestwick enables a “hub-and-spoke” model of operations. Crews and equipment are forward-positioned in Scotland, ready to support missions across multiple continents at short notice. Canadian aircraft and personnel now rotate through Prestwick on a continuous basis, keeping a year-round presence and a Canadian flag flying over the tarmac.

Prestwick’s value lies in more than just history. Its geographic position on Scotland’s west coast makes it one of the first viable European airfields for transatlantic flights. RCAF aircraft can fly directly from bases in Ontario or Quebec to Prestwick with minimal stops, rest and refuel, and continue onward into continental Europe, the Middle East, or Africa.

Additional advantages include:

24/7 operations with infrastructure capable of handling large military aircraft;

Secure facilities for storing and staging sensitive cargo;

Proximity to RAF infrastructure and access to NATO support systems;

Lower commercial air traffic, making it suitable for training and multinational exercises.

Although ATF-P is a Canadian-led initiative, Prestwick is no stranger to other militaries. The airport serves as a regular transit and refuelling stop for the Royal Air Force, United States Air Force, and even air arms from the Middle East, including Oman and the United Arab Emirates.

Prestwick’s dual-use civilian and military capacity makes it a flexible and cost-effective solution for allied logistics. Its support to exercises and real-world missions has reaffirmed its standing within NATO as a dependable air link in both peacetime and crisis.

An Air Base by Any Other Name

Prestwick might not bear the fencing, signage, or security footprint of a formal military base—but make no mistake, it plays a critical role in Canada’s global defence posture. From a trio of Hercules aircraft and a crew of 60 to tens of millions of pounds of aid delivered to Ukraine, the airport has quietly become Canada’s air base in Scotland.

Canada’s presence at Prestwick will remain central to future operations. For now, a modest corner of Ayrshire continues to serve as a bridge between continents, sustaining not just aircraft, but alliances.

ukdefencejournal.org.uk/skiesmag.com

Subject: Survival Courses

Good morning Tony,

When we were told we were off to the swimming pool at Seletar, it was big smiles and jollity until we got there and were told to kit up in flying suits, leave our shoes on and put on a "Mae West (she didn't complain!)". Ordered to the top diving board and await to be told to jump! I can swim and I'm not afraid of heights, but poor Taff was scared of both. At the given time a gentle push made sure Taff conquered his fears.

The following day we went for a "cruise" out into the Straits of Johor to be thrown into the sea and winched back into the Marine Craft Section (MCS) boat. Thrown overboard, the Coxswain shouted "Don't worry about the sharks and sea snakes, we've thrown in some repellant!"

Sharks? Sea snakes? We were in the water for about 15-20 minutes when a Whirlwind approached us and a kind gentleman hooked us up and dropped us back on the boat. A lesson learned... Don't touch a metal floor, wet, after being winched, it does clear the wax out of the ears!

Best regards

Barry

Subject: Survival Courses

Hi Tony,

In 1970, during my army days, I was sent to Borneo for the Jungle Warfare Course. The fun of wading through swamps with the leeches and various other creepy-crawlies was quite something, but we had a fantastic time with the Gurkhas!

Halfway through the course we hosted a visiting Brigadier and his wife. All our kit had to be laid out on a long table to show what we had to carry etc. The inspection was going well until the Brigadier's wife saw a packet of condoms on the table. She turned to the Sergeant Major and said, "I did not think the men would have time for that sort of thing, I think they should be removed immediately!

Sergeant Major says to her, "No madam, you have got the wrong end of the stick. The condoms are worn to keep the leeches off the men’s privates."

She responded, "Well, what about the other ranks? Sergeant Major has a total look of disbelief! The Brigadier said, “Come along dear.”

I got in trouble for asking her if she wanted a demonstration! Sergeant Major nearly choked laughing but said he wish he would have thought of saying it first. I passed the course and returned to the UK for one weeks' leave. The day after returning from leave the Army’s sense of humour was to send me to Tromso, Norway for winter survival training. You know what they say, if you cannot take a joke you should not have joined! I really enjoyed Norway.

All the best

Graham

Air mobility is essential in these efforts. It turns transport into a strategic necessity, allowing for the quick movement of vital supplies across various operational areas. Air mobility not only includes airlifting, sealifting, and pre-positioning supplies, it also includes maintaining the safety of the route so the 13 nations of this strike group are protected throughout the transit.

The RAF's support for Carrier Strike Groups goes beyond logistics; it is vital for keeping aircraft carriers and their escorts operational.

Group Captain Andy McIntyre, Commander Air Mobility Air Wing said, “The RAF Air Mobility Force will supply the Voyager, C-17, and A400M during this important operation. We are providing air-to-air refuelling with many Voyagers along the route, as well as logistical support from C-17 and A400M, including pre-positioning supplies and personnel. We are also ready for aeromedical recovery if needed. What sets the RAF apart is our speed and range. We can deploy over long distances with meaningful payloads. We can be wherever the CSG needs us ahead of time, managing changes to their program and offering support along the way.”

Timely delivery of fuel, ammunition, and supplies is crucial for sustained operations at sea, especially for an operation like Highmast that involves thousands of personnel at sea for months. This collaboration with naval and land forces is essential for enhancing the overall capability of the UK military.

As the CSG embarks on missions in the Indo-Pacific region, air mobility's importance grows even more. By integrating air mobility into the CSG's strategy, the UK military confirms its readiness to respond to global threats. The RAF's capabilities not only improve logistics but also support rapid deployments, medical evacuations, and other vital services for joint military operations.

Serving as a versatile hub for humanitarian assistance and as a deterrent against threats, the 65,000 tonne aircraft carrier relies on three factors to ensure its safety and success: proximity to objectives, availability of key resupply points, and the ability to secure air and sea routes.

Without a reliable resupply chain and limited air defence, the impact of the CSG's agility poses a security challenge. Operating at a safe distance from potential threats while ensuring strong logistical support requires careful planning which has been a priority for the RAF for several years. As the CSG sets sail, the plans will be tested along with capability to navigate stealthily while remaining well-supplied which is essential in dynamic maritime environments.

As the CSG navigates the complexities of modern warfare, the RAF's commitment to air mobility remains a cornerstone of the UK's defence strategy. This coordinated effort guarantees that the Armed Forces are ready for quick responses and can project power globally, reinforcing the UK’s status as a dominant military force on the world stage.

raf.mod.uk

Subject: Survival Courses

Morning Tony,

I can't really offer much to this month's subject as I personally never had to attend any survival courses. However, having said that, I do remember when as a very young SAC working in the Electronic Supply Group (ESG) at RAF Leuchars, a notice came out on SRO's requesting volunteers for "Wet Winching" rescue practice for 202 Squadron. The idea was to drop the volunteers into the River Tay Estuary, go around and then pick them up again.

Two of the girls in ESG volunteered to go and asked me if I fancied it? "No chance!" was my reply. "For one, I don't trust helicopters and if I want to get wet, I'll either have a bath or a shower thank you very much!"

Regards

Steve

Subject: Survival Courses

Hello Tony,

My offering is about a life raft drill performed in Singapore Harbour while I was a member of 48 Squadron, Changi, in the mid-sixties.

Our group of heroes assembled on the side of a boat dock, an MS9 life raft had already been launched and turned upright. In our group we had a very senior Master Navigator named Mr Bale, or "Buff" to his close friends. A very enthusiastic young Sergeant called out, "Come along Mr Bale, jump in the water and swim to the life raft."

Buff replied "Young man, water is for shaving and making tea. You bring the life raft over here and I will embark, I have no desire to get wet or go for a swim. I have done this drill many times, so my ability to swim will not be in doubt!"

And so, off we went in the MS9 raft (the Hastings carried six; four in the wings and two in a luggage rack).

Out in the harbour there were some single-seat life rafts. We paddled over to one and invited the occupant to come in with us. A jolly time was had by all as one member had a bottle of Scotch and there were also fags [cigarettes] and a variety of sweets and biscuits. After a while we were recovered by helicopter, picking up the single seaters first; it was unfortunate that our invited guest's life raft blew away. I will leave you to imagine the later problems and meetings that the powers that be had as they did not see anything amusing about our antics!

Mick

(Originally broadcast in July 2021)

UKMAMS OPERATIONS 1967- 1992

6-24 Nov 1967 |

Aden evacuation. 6 teams to Bahrain. |

28-30 May 1968 |

Operation Ephod: One team deployed with 1bn Battalion Royal Inniskillings to Bermuda to maintain civil order after riots. |

Mar-Aug 1969 |

Operation Sheepskin: 1 team deployed to set up a movements organization in Antigua during hostilities in Anguilla.

|

15 Aug 1969 |

Operation Spearhead UKMAMS set up movements organization in Northern Ireland.

|

28 Jun 1970 |

Operation Marginal: 3 UKMAMS teams reinforce Northern Ireland.

|

21 Sep - 8 Oct 1970

|

Operation Shoveller: 1 team to Jordan to assist in the evacuation of refugees during Jordanian Civil War and deploy army surgical team to Beirut and Amman.

|

3-8 Aug 1971 |

Operation Banner/Four Square: 1 team to Northern Ireland.

|

8-13 Dec 1971 |

Operation Hamish: 2 UKMAMS teams deployed to West Pakistan for evacuation of British nationals from Karachi and Chuklala to Masirah during the Indo-Pakistan War.

|

Jan 1972 |

Airlift of Grenadier Guards to British Honduras in response to Guatemali threat.

|

28 Jul 1972 |

Operation Glass Cutter: Deployment of Queens Own Highlanders to Northern Ireland.

|

28-31 Jul 1972 |

Operation Motorman: Deployment of Royal Engineers to Northern Ireland to remove IRA no go areas.

|

26-31 Oct 1973 |

Deployment of UN peacekeeping force to Cairo after Yom Kippur War.

|

Oct-Dec 1973 |

Operation Lukan: Movement of refugees between Pakistan and Bangladesh.

|

July-August 1974 |

Operation Ablaut. Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

|

4 Nov - 19 Dec 1974

|

Belize Emergency: 1 team. |

May 1977 |

Operation Banner: General strike, Northern Ireland. Deployment of specialists to maintain essential services and airlift of bread from Liverpool.

|

Jul 1977 |

2nd Belize Emergency: 4 teams deploy.

|

31 May - 13 Jun 1978 |

Lebanon Crisis: 1 team to Fiji and 1 team to Tel Aviv for deployment of UN Peacekeeping force.

|

Aug 1978 |

Iranian Civil War: 2 teams enter Iran to evacuate British nationals.

|

19 Dec 1979 - Mar 1980 |

Operation Agila: Stabilization of Rhodesia. 3 teams deployed to Salisbury and 2 teams to Nairobi.

|

12 Jun - 28 Aug 1980 |

Operation Titan: 1 one team to Vanuatu, New Hebrides with Royal Marines during unrest.

|

2 Apr - Jun 1982 |

Operation Corporate: Argentinian invasion of Falklands Islands. 4 four teams to Ascension Islands. 1 team allocated to special forces covert operations.

|

9 Sep 1982 |

Lebanon: 1 team deployed with Buccaneers as peacekeeping force.

|

16-20 Jan 1986 |

Operation Balsac: Civil War Aden. 1 team deployed to evacuate British nationals.

|

Aug 1989 |

Namibia: Deployment of peacekeeping force during build-up to independence.

|

Aug 1990 |

Operation Granby: Whole of UKMAMS involvement in liberation of Kuwait from Iraq invasion. Operation Haven: Logistic support of force protecting Kurdish people from Iraqi reprisals.

|

May 1991 |

Operation Warden deployment of Jaguars to Adana to overseas safe haven.

|

Aug 1992 |

Operation Jural: Deployment of Tornado/ VC10K to Dhahran and Bahrain to monitor Iraqi Southern Exclusion Zone. |

1 May 1966 |

Zambian Oil Lift: 1 team in Lusaka Zambia, 1 team in Dar es Salaam Tanzania and 1 team in Nairobi Kenya. |

26 Aug - 4 Sep 1966 |

Operation Aloe: Zambia |

Feb 1967 |

Belize Hurricane: 1 team deploy to receive relief supplies. |

22 Mar 1967 |

Torrey Canyon Oil Tanker Disaster: 1 team deployed to Edinburgh to onmove oil dispersant equipment.

|

2-24 Apr 1970 |

Eskisehir: 1 team to provide earthquake relief in Turkey.

|

30 May 1970 |

Bucharest: 1 team for flood relief in Romania.

|

19 Jun 1971 |

Calcutta: 1 team for famine relief in East Pakistan.

|

10-16 Aug 1972 |

Operation Delivery Boy: 3 teams to provide aid to Scottish Islands.

|

26 Dec 1972 |

Managua Airport: 2 teams providing earthquake relief supplies to Nicaragua. |

29 Jan - 6 Feb 1973 |

Khartoum: 2 teams, providing relief supplies for Sudan. |

24 Feb - 11 Apr 1973 |

Operation Khana Cascade: 1 team to Nepal to set up airhead for preparation and airdrop of 2,000 tons of grain to the Nepalese. Team assisted with the air dispatch.

|

7-13 Apr 1973 |

Algiers: 2 teams deliver Red Cross relief stores. |

July 1973 |

Cambodia: 1 team deliver Red Cross supplies to Phnom Penh during war with Vietnam. |

21-27 Aug 1973 |

Pakistan: 2 teams deliver medical supplies boats for flood relief. |

Aug 1973 |

Operation Sahel Cascade: 2 teams airlift 4000 tons of grain from Senegal to the Sahel region of Central Africa. |

22 Dec '74 - Jan 1975 |

Australia: 1 team deploy relief supplies to Darwin following Cyclone Tracey. |

8 Sep - 1 Nov 1975 |

Angola/Portugal: Relocation of refugees and Portuguese nationals between Luanda and Lisbon. 75 UKMAMS personnel involved.

|

Dec 1976 |

Eastern Turkey: 2 teams delivery of earthquake relief supplies to Van. |

Dec 1977 |

India: 1 team deliver Red Cross vehicles to Bombay during India disaster relief programme. |

23 Mar 1978 |

Amoco Cadiz Oil Tanker disaster: 1 team deliver oil dispersal equipment to Guernsey. |

19-21 Jun 1979 |

Jamaica: 1 team deliver flood relief supplies. |

13 Jul - 1 Aug 1979 |

Nicaragua: 1 team based in Panama, airlift Red Cross supplies following civil war |

1-5 Sep 1979 |

Dominica: 1 team deployed to provide assistance in moving relief supplies. |

Nov 1984 - Dec 1985 |

Operation Bushel: Famine relief in Ethiopia. |

21 Jun - 3 Jul 1985 |

Nepal/Sri Lanka: 1 team delivery of medical supplies to Kathmandu and Columbo.

|

Sep 1989 |

Monserrat: 2 UKMAMS personnel delivery relief supplies in the wake of Hurricane Hugo. MAMS personnel were later to receive commendations.

|

Jan 1990 |

Eire-UK: 1 team collected emergency electricity repair teams from Dublin and Aberdeen for southern England after severe storms caused considerable damage.

|

8 Apr - 5 May 1991 |

Operation Provide Comfort: 1 team deployed to Incirlik Southern Turkey in support of relief aid air drops to Kurdish refugees.

|

July 1992 |

Operation Cheshire: delivery of supplies on behalf of UNHCR from Zagreb to Sarajevo, the former Yugoslavia.

|

(Both items extracted from "UKMAMS - Moving in Mysterious Ways" by Jeremy D Porter)

|

|

Subject: Survival Courses

Good Day, Antonio,

Before I waffle on, many thanks for what you do for the rest of us. The monthly missive is well looked forward to, received and digested. If it doesn’t arrive, there is a hole in the fabric of life. ¡Muchas gracias, Señor.

Partook of two survival courses; jolly old Jungle Survival from Changi prior to Bersatu Padu, and the Sea Survival at Mount Batten.

I can’t quite remember how I came to be standing in front of Mike Slade who was enquiring as to why I could not swim, to wit yours truly replied that if it was absolutely necessary for me to emulate Aquaman, then I would. At that stage of life, I hadn’t yet recognised as to when to keep big gob shut! There were several of us in the same situation.

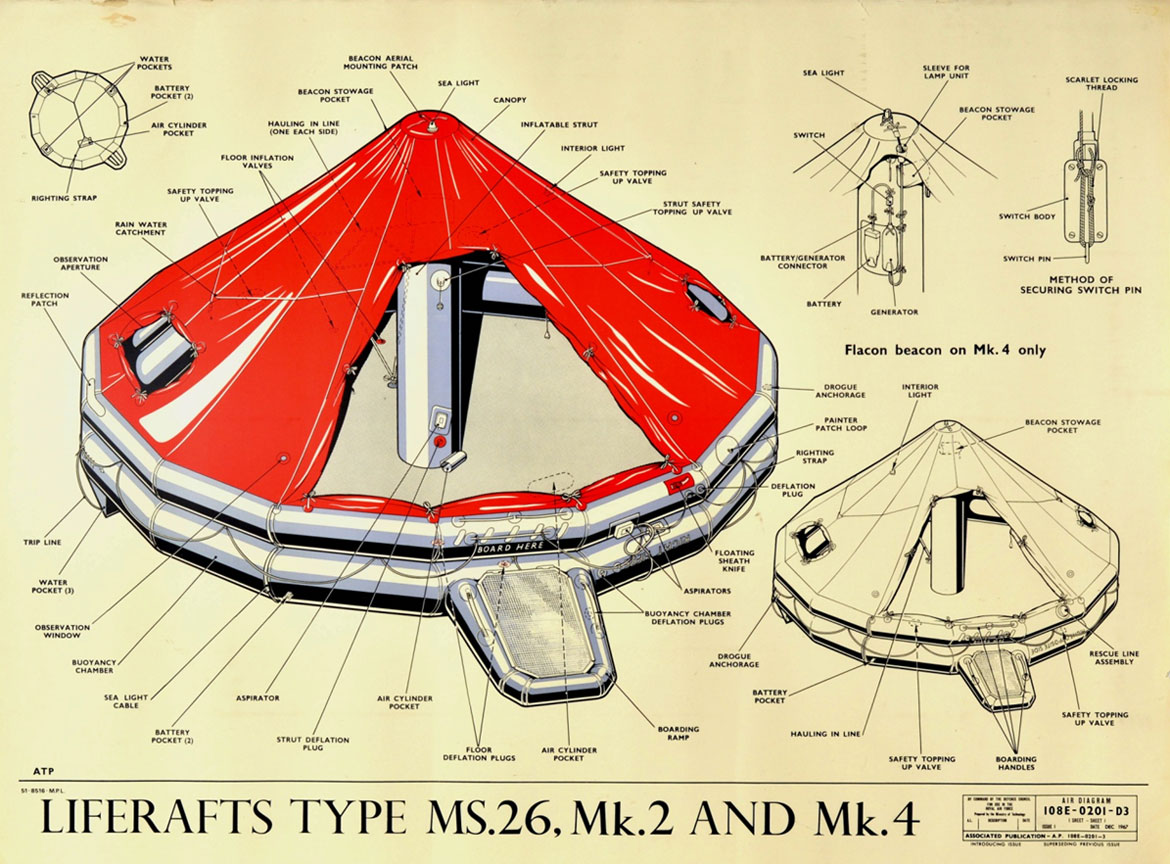

Pretty soon after that, in a cold February, we found ourselves at Mount Batten, seriously taking in what our instructors´ were telling us. Came the day, robed in immersion suits of various states of u/s-ness, ciggies, lighters and specs in various parts of said suits, we were embarked in the super looking motor launch Skylark for our trip round the bay. MS26, still packed, heaved over the back of the Skylark... **BOOOOFFF** MS26 opens. As yours, Tony, downside up.

Ooops. Floatation jackets inflated, we were invited to take the waters of the grey/green English Channel. “Don’t worry, lads, you have 45lbs of buoyancy, you won’t even get your hair wet”. As the water above my head transited green-grey-black I wondered why the dear instructor had fibbed to me! Nominated to get our ship on an even keel, this was completed with no fear whatsoever (LIAR!). All on board, doors shut, pump up the floor, ciggies out and it was surprising how quickly the interior warmed up.

Then, the delightful crew of the Skylark started handbrake turns around our life support machine. One of the incumbents decided he needed to play the porcelain trumpet. Threw himself at the door and hurled. Just as one of the instructors decide to make an entrance. Fortunately, the oggin cleared everything off of him. Did us larf? Oh yes. To finish the exercise off, the Whirlwind that was due to winch us from the MS26 went u/s so it was back to port by sea.

It came out at the course wash-up that the great majority of students couldn’t swim, which did not go down well. For me, I thought it was a great experience and I learnt a lot from it. Fortunately, never needed to put what I did learn into practice. I still cannot swim, but I made sure my children could.

Take care everybody and look after each other.

Regards,

Syd (El Cid)

“As we look at agile employment of aircraft for the Air Force, being able to deploy to remote locations and run sustained operations, this was a huge proof of concept for us,” observed LCol Steve Thompson, days after returning from the largest Operation Nanook-Nunalivut the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) has hosted in the 17 years since the annual Arctic training event was first conducted in 2007.

Op Nanook is an all-domain defence and security operation that brings together Regular and Reserve elements from across the CAF, as well as international partners, to test combined and joint interoperability in a variety of sea and land-based scenarios and often under extreme conditions.

Thompson, the commanding officer of 440 Transport Squadron, based in Yellowknife, N.W.T., led an Air Task Force (ATF) of almost 150 personnel from across the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and from the U.S. National Guard to support a wide range of missions in the vicinity of Inuvik and Beaufort Delta.

Over three weeks in late February and early March, as temperatures dipped at times below -50ºC with the wind chill, the ATF aircrews, maintenance technicians and logistics personnel maintained an around-the-clock op tempo not previously recorded on Op Nanook.

Operating from the NORAD facility at the airport in Inuvik, the ATF featured a modest fleet of eight aircraft: two ski-equipped Twin Otters from 440 Squadron; two CH-146 Griffons from 430 Tactical Helicopter Squadron in Valcartier, Que.; two CH-147F Chinooks from 450 Tactical Helicopter Squadron in Petawawa, Ont.; a CH-146 Griffon from 417 Combat Support Squadron in Cold Lake, Alta.; and a LC-130 Hercules with skis from the 139th Airlift Squadron of the 109th Airlift Wing of the New York Air National Guard.

But over the course of Op Nanook, they flew 413 hours, conducting 184 missions that involved the movement of over 420 passengers and more than 210,000 pounds of freight.

Much of that was aided by a headquarters staff, mostly from 440 Squadron, as well as members from 436 and 429 Transport Squadrons in Trenton, Ont., 412 Transport Squadron in Ottawa, plus members from 8 Air Maintenance Squadron and 8 Operational Support Squadron in Trenton.

The missions, too, broke new ground, sling loading vehicles and moving large numbers of troops over challenging terrain.

The Twin Otters concurrently provided airlift and route reconnaissance for the 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group, which conducted a patrol over a mountain pass from Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., to Old Crow in the eastern Yukon. The patrol was supported by regular food and supply bundle drops from a Twin Otter, and had a broken skidoo airlifted out by a Chinook.

The Griffon and Chinook helicopters provided support to the International Cooperation Engagement Program for Polar Research, a global team of about 25 military and civilian personnel performing experiments on clothing, weapons mounted on skidoos, and other equipment under Arctic conditions. Employing a HUSL (helicopter under slung load) net, the Griffons transported food, water, fuel and other supplies to a remote camp for almost two weeks.

“They were doing a lot of human factors testing as well, how the body reacts in extreme conditions, and with different clothing,” Thompson explained.

The testing also involved a new U.S. Army Cold Weather All-Terrain Vehicle (CATV), a newer variant of the Canadian Army’s BV-206.

The fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft also supported the Advanced Naval Capabilities Unit, a small team from the Royal Canadian Navy testing aerial and underwater drones, transporting people and resupplies of food, water, and other essentials to Reindeer Station — northwest of Inuvik on the Mackenzie River.

Working with the Canadian Special Operations Regiment (CSOR) from Petawawa, a CH-147F crew conducted the first-ever sling load operation of a BV-206, transporting the all-terrain vehicle from Tuktoyaktuk to Inuvik. The Chinooks also provided airlift for CSOR throughout their area of operations.

The largest mission task, though, involved the insertion of troops from 37 Canadian Brigade Group (CBG), reserve units from 5th Canadian Division. Employing both Chinooks and the Twin Otters, the ATF first inserted a platoon at Shingle Point — a site known as Bar-2 on the Distant Early Warning Line.

The Chinooks then moved a platoon of soldiers and skidoos to Bar C, or Tununuk Camp, where they then conducted a security patrol to a third DEW Line site.

On the last day of Op Nanook, the ATF moved a platoon from 37 CBG to Bar BA3 to conduct manoeuvres.

For Ontario- and Alberta-based squadrons, it was an adjustment for them to operate where the treeline ends and reference points disappear in a white blanket of snow that offers few visual cues and can play havoc with depth perception.

“There’s really no contrast to be able to pick out land features,” Thompson noted. “That was a different experience for those that are used to flying in the south.”

The cold conditions and firm snow base, however, proved ideal for ski landings. “It was probably the best ski conditions we have seen in a long time,” he said. “Everywhere [aircraft] needed to go, they were able to get into. The lakes and the ocean were not too severely drifted, so it wasn’t too bumpy. We got a lot of excellent flying and ski experience-building on this operation.”

Operating out of the NORAD facility in Inuvik, the ATF was able to keep its Griffon helicopters in a warm hangar overnight, while the Chinooks parked in a nearby “green hangar” acquired in 2024 by the federal government.

“The maintenance crews knocked it out of the park. The whole time we were up there, they were working long hours anytime there was an unserviceability. The units were well prepared with their pack up kits and the maintenance teams they had, and they were normally able to turn maintenance tasks around relatively quickly so that the aircraft were back operating with a limited time away from my mission tasks.”

The operation highlights included an early evening redeployment of members of CSOR and 50,000 pounds of equipment with just two Chinooks, and the integration of the medium-lift helicopters with the Twin Otters to insert 37 Brigade.

The most consequential for the ATF, though, was building the landing area on Parsons Lake.

“The normal process to build a ski landing area takes around two weeks to pioneer a site, build a camp, and groom the strip — depending on snow conditions. This year we completed that process in just over three days,” said Thompson. “The Polar Camp Skiway team and Ski Landing Area Control Officer team knocked it out of the park. Following the successful landings of the LC-130 Ski Herc, the teams had the camp packed up and off the ice in an afternoon, which is also an incredible feat."

While the tactical helicopter squadrons frequently train and operate together, and 440 Squadron has worked often with the 109th Airlift Wing, bringing all the assets together under an ATF — especially the combat support squadron — is rare, Thompson said.

“It was the largest Air Task Force we’ve ever had on Op Nanook — probably the busiest Air Task Force we’ve had — and everyone just got it done,” he told Skies. “Not to sound cliche, but it was truly a Canadian thing where we took all these challenges, put our heads down, and the whole team pushed through it.”

April 13, 2025 at 3:18 pm

Lorna Johnson says:

I am 95 and found this very assuring and exciting. Having moved from just “Eskimos” being looked down on and us not appreciating their skills, to the time we made them destroy their dog teams and introduced Skidoos which they, much to the government's surprise, learned to use quickly. This is a remarkable wake up of our need to learn to live in this terrain. Hope we now respect our native people but I have my doubts . Glad we are learning to survive as have they, but we need this sophisticated equipment to do so. Are we coming awake to our need to protect this part of Canada? I hope so as we will otherwise lose it to more aggressive countries.

skiesmag.com

Subject: Survival Drills

Dear Tony,

In 1965 I was posted to Mount Batten as storeman to the School of Combat Rescue and Survival. Therefor I am aware of what you went through.

Apart from escape and evasion exercises on Dartmoor (spooky), I was often invited to assist with the sea survival drills. One day I was asked to join in a drill; I don’t know why I accepted as I can’t swim and because of that I was classed as the injured man. Of course the MS5 was upside down. I drank a lot of the English Channel that day. The things we do for fun!

Best regards

Rae

Subject: Survival Courses - Sea

Hello Tony,

Just sitting having a breather with an ice pack as a result of total knee surgery last week, so it’s an ideal time to remember that Sea Survival training and stop looking at a double sized right knee!

On a cold day late in January 1982, 5 or 6 of us from a couple of teams in a short wheel-based Landrover and trailer were en-route to RAF Mount Batten. Just over halfway, on the M5 motorway, ‘cruising’ steadily and as comfortably as possible for the fellas in the back, suddenly the monotony was broken by an horrendous clatter from under the bonnet. I pulled over, stopped and switched off engine, nothing visual on inspection of the engine and noise still there on start up. As far as I remember I spoke with MAMS Ops as to whether we continue but as we were over half way I asked them to contact MT Section at Mount Batten to advise them we’d drive slowly there; I thought we’d had a valve jump a guide. As it turned out that was the case, MT fitters fixed the problem that night.

Anyway, getting to the reason for going, very similar to your narrative Tony.

There was a fair amount of classroom work, then being dropped in the rough sea from the Pinnace. I remember we had fewer numbers than you had for the exercise required for the MS26 having to right the capsized dingy/life raft. It was soul destroying treading water with numerous attempts to flip the dingy over in the swell and wind. We seemed to be in the water an interminable length of time and already feeling sick. When we did right it, the few of us did get over the side walls into the raft and collapse trying to gain some semblance of order, that was when the time waiting sitting, wallowing on that sea swell and waiting for winching up was, as far as I felt the worst physical and mental experience of my life thus far at age 39. It never crossed my mind about rescue! Those futile thoughts of mine at the time were such that in a real life incident my emotions were what it would be like to accept one’s fate and just give up.

Eventually a head pokes in, shouting "Get out, you’re next!" - back into the cold and heaving swell, then Winchman (Loadmaster?) harnesses me and I’m winched up in tandem with him to the hovering Wessex.

Back at the classroom for debrief we are all given a tot of rum to warm and liven up our wet bodies and brains, then hot showers and warm clothes.

As Search and Rescue has long been privatised, do Mobile Support Crew continue to undergo Practical Sea Survival training, or is it just for Aircrew?

Thanks Tony, looking forward to other people’s experiences.

Regards,

Gordon

With a decade of RAAF flying operations under its belt, the C-27J Spartan, operated by 35 Squadron, has often been the first on the ground, delivering vital supplies, personnel and equipment to those who need it most.

Wing Commander Seery said, “Being the Commanding Officer of 35 Squadron is an extreme privilege; it was my first choice for command and the place I really wanted to get back to,” he said. “To be able to return and contribute to this phenomenal culture and witness how it’s grown over the years is really exciting.”

The day was also a reminder of the unique camaraderie that Royal Australian Air Force aviators share. “It’s like all things in Defence: you separate, you get back together and it’s like good old times and things haven’t changed,” Wing Commander Seery said.

The first of 10 C-27J Spartans arrived in Australia in 2015 from prime contractor L-3 Waco, Texas facility. With its rugged durability, advanced avionics, self-protection systems and impressive payload capacity, the C-27J Spartan has become a primary platform of the ADF’s airlift capabilities. The aircraft enables personnel to deploy quickly and effectively to any corner of the globe, including in contested environments.

Widely known as ‘Wallaby Airlines’, the aircraft bridges the gap between the Army’s rotary-wing assets and the Air Force’s larger fixed-wing aircraft. “There’s definitely crossover in role and performance capabilities between the C-27J Spartan and the C-130J Hercules, C-17A Globemaster III and the CH-47 Chinook, but it has a very unique and niche capability now widely valued in the ADF as well as our regional allies and partners,” Wing Commander Seery said.

With a high operational tempo, the squadron’s support to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief missions has built a powerful and positive reputation both within Australia and overseas. “The rate of effort is consistent and keeps us quite busy, particularly our operations out of Papua New Guinea, Fiji and the Southwest Pacific,” Wing Commander Seery said. “We work hard on this platform day in and day out to deliver effects for the Australian Government and other nations that we support. The culture here is phenomenal – the team look after each other, everyone enjoys deployments together, getting after it and getting the job done.”

contactairlandandsea.com

https://australianaviation.com.au

Subject: Survival Courses

Hi Tony

(Originally published in a civilian aviation enthusiasts' newsletter)

Once I had completed this course I thought that was me set to travel the world without a care. How wrong I was! After just one task to Calgary in Canada I was told I had been selected for a Sea Survival course at RAF Mount Batten.

Mount Batten at that time was a RAF Marine Craft Base and also housed the RAF Survival School. The base was the home for many of the RAF maritime trades (Boaties) and the survival school was manned by members of the RAF Physical Education Branch (PTIs). Mount Batten was located on a peninsular on the north side of Plymouth.

There were four MAMS personnel ‘selected’ for this course and along with myself was an SAC, a Corporal and an Officer. The Boss was accommodated in the Mess on base whereas we poor rankers had to stay in a Guest House and claim rates. We all drove down from Abingdon on the Sunday as it was a week-long course.

Monday morning, with not too much of a hangover, we all congregated in the classroom. There were about 16 of us on the course and the others were a mix of ‘fast jet’ (Lightning) pilots, a Vulcan crew, a very wizened old Navigator flying Canberra's, a Master Engineer from Shackleton's and two very cocky co-pilots from 53 Squadron who operated Belfast freighters.

Our Instructor, who was with us all of the time, was Flight Sergeant ‘Geordie’ Platt; a fountain of knowledge and a great sense of humour. Although the course was primarily about sea survival with a constant referral to ”When you are put to sea on Friday...” other areas of survival were mentioned too, including, Desert, Jungle, Winter, Arctic and Temperate survival.

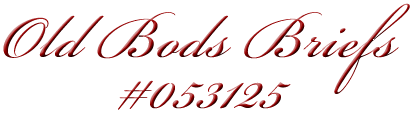

We were also introduced to single-seat inflatable life raft dinghies, as strapped to an ejector seat. The MS5 (Multi-Seater 5 man) as used by V-Bomber crews, MS10 and then all the way up to a MS26 as carried by the Air Transport Fleet.

Once we were shown how to inflate all of these we were then appraised of their contents and how it all functioned. Solar stills, drogues, repair kits, rations and water, and pumps to reinflate.

We were all issued with life jackets/life vests too and constantly warned NOT to inflate them once on the RAF launch or those at the end of the boat will go for an early swim. The contents of these jackets/vests were also explained and as some contained a SARBE beacon the operation of this was also taught.

It was also apparent that the larger the dinghy the larger the CO2 bottle required to inflate it. If the larger dinghies did inflate upside down the only way to get them back to the right way up was to climb on board. Then grab hold of some straps and whilst standing on the gas bottle, lean back and heave on the straps and pull them in. This would eventually bring the dinghy upright and then once passed the horizontal it would fall back on top of you having righted itself. All you had to do then was take a deep breath and swim out from underneath. He was also the first person I ever heard use the expression “Sense of humour failure!”

He had also mentioned that deadwood, especially silver birch, was great for making fires. More than once he witnessed a perspiring student cutting down a tree with an axe. When he started to drag away the log, Geordie would rock the stump and pull it out telling the student not to forget it. To this day I remember his comment seemingly made by the North American Indians – "Red man make small fire and keep warm. White man make big fire and keep warm chopping sticks." Years later I completed a “Fitness for Survival” Course at Grantown-on-Spey in the Cairngorms. The earlier advice still stuck with me.

Whilst covering Jungle Survival for a couple of hours, he talked about the person carrying the ‘snake stick’ being the most unpopular man on patrol. The stick is used to catch and retain a snake and in theory it would be used to bring back the offender of a snake bite. Up till then nobody wanted to be behind the man carrying it and so he was always put at the rear. His troubles increased if he ever caught a snake as everyone would give him a wide berth.

Some three years later I was stationed in Singapore and often met the students having a weekend break from the real Jungle Warfare School near Johor Bahru in Malaya. The OC of the school at that time was Major Blashford-Snell, a famous explorer. In later years I also visited the jungle survival school in Sibun, Belize, whilst ‘doing the rounds’ in a Puma helicopter. Fortunately for me we only stayed an hour for a coffee and then flew out again.

Before we went back to our sea survival training we were also briefed on the basic aspects of Desert Survival and basically the brief is to stay with the downed aircraft if at all possible. I knew from experience, whilst stationed at RAF El Adem in Libya, that most who did this did not survive. Whilst in Libya, I dearly wanted to go out with the Desert Rescue Teams and see the Sand Seas which were hundreds of miles away inland. Unfortunately I couldn’t as there was a sensible standing rule that everyone who went must hold a driving licence – at that time I did not.

Back to Sea Survival training, we were tested on the contents of the dinghies and how all the equipment and apparatus worked. More training with pyrotechnics, heliographs too, to attract attention. How to get yourself into a dinghy, assist others, inflate the floor, put out the solar still and close the door panels and make yourself seaworthy. We were also taught how to use the standard rescue harness as used by SAR helicopters as we were due to be winched from the sea/dinghy at endex.

Eventually, the engines stopped and all was quiet. We (students) were now pretty subdued and somewhat apprehensive. The Lightning pilots were ‘invited’ to step off the side of the boat, life preservers inflated and commenced inflating their single seat dinghies and climbed aboard them. At the same time, the launch crew had put over the side a MS26 dinghy and once it was inflated, they carefully ‘flipped’ it over using boathooks. Our instructor, Geordie, then said he would need two volunteers to right the dinghy. We had also been briefed that until this happened no students could enter the water, as in the past the bobbing heads looked like inviting stepping stones onto the raft! “You two Sirs, thanks for volunteering!” he said pointing at the now timid co-pilots. Lifejackets inflated, in they went and swam towards the overturned life raft.

As an incentive to get this done the RAF launch was now tearing passed us at a great rate of knots, creating a bow wave in an attempt to swamp us! Inside the dinghy I witnessed several events. Notwithstanding what appointment they held, certain students just sat there apathetically, while others struggled to motivate and one or two ‘took the reins’.

After what seemed an eternity, the DS were satisfied we had suffered enough and also shown our ability to work the equipment we had. Unfortunately for us the promised helicopter rescue did not materialise as the Whirlwind had been diverted to a ‘real shout’.

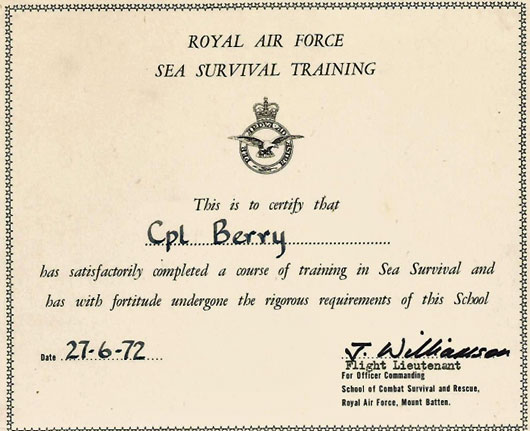

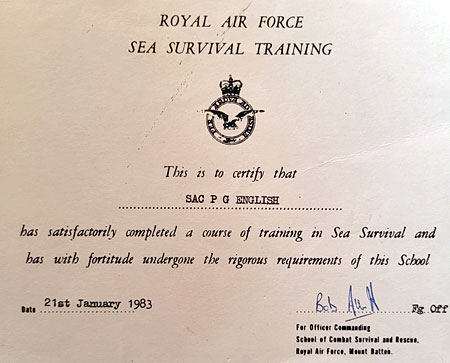

Once we disembarked we were marshalled straight into a shower block where we had a hot shower and changed back into dry clothing. At this stage in winter months the students were given a tot of rum – not this time! Morale started picking up and so did the chatter. The final thing to happen before dispersal was a debrief, critique and the awarding of certificates as shown at right.

What did I learn from this course? I became a bit selfish and always thought “look after number one first” – self preservation. Everyone is different and some people have that extra ounce of courage in them, I could never be a hero! Never annoy the instructors and try and be a ‘grey man!’

Best regards,

Ian

The simulator, essential for training RNZAF pilots on the advanced P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft, required precise handling due to its delicate electronic components and substantial dimensions. Antonov Airlines deployed one of their AN-124 Ruslan aircraft for this mission, one of the largest cargo planes in operation globally with its distinctive nose-loading capability perfectly suited for such specialized cargo.

https://aviationphotodigest.com

Subject: Survival Courses

Wow Tony,

Talk about an epic sandbag dragging and lamp swinging opportunity! This is the closing chapter of my extinguished career in air transport. In the interest of brevity, I will précis my 20 years of Safety Equipment and Procedures (SEP) crew training at British Airways (BA).

I can neither deny, nor confirm any previous RAF Troodos winter survival incidents. It was a long time ago!

My dip in the channel was Feb 1977, during the last of my 12 years RAF service. I also recall my head being used as a boarding step into the dingy by my "mates?" of Golf team, whilst I wasted never to be regained seconds of my mortal coil, searching for the elusive golden rivet of the mythical air gap allegedly beneath the raft, my experience closely echoed yours Tony; obviously SOP for junior ranks. This course was my total epiphany. I was in complete awe of the dedication, enthusiasm, empathy, clarity and commitment demonstrated by the instructors. It prompted my application for a training job just 2 years later, having completed a full year as a cargo handler with what was then a respected airline (BA 1970s).

10 years of cargo training led to a year of DG consultancy, seconded to the North Sea offshore oil and gas helicopter operation. This opened an opportunity with Flight Ops training as an SEP instructor. This was the boyhood of Raleigh stuff, as I learned at the feet of SAR helicopter and Nimrod retired crewmen, two of whom I knew from their ALM days. I started off with daily dingy drills with cabin crews at Hayes swimming pool (a really tough job ).

Formal qualifications were gained with; IAM, Cranfield University, FAA CAMI and CAA Fire School at Teesside. DFT security authorization was provided at Thames House and Shrivenham. This established a new career direction for this ex-SAC Movs Controller. A decade later I was a worldwide co-ordinator for safety, survival and security training for all BA and a selection of Mid-East private VIP flying staff.

During the Halcyon days of our association with the RAF specialists and 216 Squadron, I had the opportunity to take part in ocean going trials of a Tristar slideraft where my familiarity with the management of the device was appreciated.

Back to the subject of "Survival Courses", the gold standard was developed for the offshore industry by the Robert Gordon Institute in Aberdeen, now known as RGIT BOSIET, involving inverted helicopter escape underwater in zero visibility.

The most dynamic simulation I have experienced was with the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) in Poole, Dorset, with wave and wind machines, light and sound effects, conducted in sea water at ambient temperature, simulating full gale conditions. I was scared sh!tless! One of the life boat survivors quoted a Benny Hill line, "I didn't have a weak stomach, I threw it further than anyone else!".

I was fortunate to have experienced the best of BA prior to the mistaken cost cutting and acceptance of mediocrity as a corporate goal.

I have made many contacts and friends who are genuine survival specialists, from both military and academic sources. It all started with the incredible experience (and tot of Rum) gained at Mount Batten 47 years ago in the company of Eddy Morgan, Tony Neal, Joe Falkner, John Rowbottom and a very young Rod Elliott.

Thanks for the opportunity to share giggles and the lifelong effect this course had on me and my colourful post service career; not forgetting the duet Eddy and I maintained moral with the classic Muppets: "Mnom mnom".

Pete

Carried out by 1312 Flight, a part of 905 Expeditionary Air Wing based in the Falkland Islands, the special mission was supported by 47 Air Dispatch, Number 30 Squadron, and Number 70 Squadron, all on deployment from their home base at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire, England. According to an RAF statement, “the drop was conducted at a height of 3,000 feet (914m), something that is challenging to achieve within the UK, and has been valuable in providing proof of concept for large scale drops which could be used in support of Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief operations. This A400 air drop has shown what a great Whole Force training opportunity being stationed in the Falkland Islands presents for British Forces,” said Group Captain Adele Stratton, Deputy Commander of the British Forces South Atlantic Islands. “We have received fantastic support from the whole local community, but especially the Goose Green Community and Royal Falkland Island Police, without whom it would not have been possible. This air drop was the culmination of a lot of hard work by personnel in the UK and here in the Falkland Islands, and it sets the benchmark for opportunities in the future.”

aerotime.aero

Subject: Survival Courses

Hi Tony,

Interesting that this topic is being mentioned, as only last week I was going through my folder and my course certificates.

November 1982 saw me posted to the Joint Helicoper Support Unit (JHSU), for a 3-year tour on helicopters and in January 1983, myself and a handful of others took a 3-hour trip to RAF Mountbatten near Plymouth. Having grown up there and knowing we were going to get wet, I knew that Plymouth Sound was not exactly a friendly environment to be jumping into in the middle of winter. I had previous experience of sea canoeing with the Air Cadets there.

After finding our accommodations, we went to the mess (or as my army colleagues call it, the Cookhouse) for dinner. I have to say, it was probably one of the best messes I had experienced in my career. We ventured into town and partook of a few hostelries and bumped into an old cadet mate of mine whose Dad knew several places and got in under "mates rates".

The boats used on the course were from the Marine Craft Unit, whose primary role was to rescue downed aircrew. They were rather nippy across the water and being "launched" overboard at speed was quite an experience I hasten to add. As Tony has stated in his recollection of his course, we had to make our way to the MS26 raft which, if you were lucky, had landed the right way up. Mostly they did but if yours was upside down it was no mean feat to right it. Cold, wet and miserable, climbing up one side to get the straps then launch yourself backwards to get it right side up was indeed a challenge, as well as climbing inside. The task still wasn't over; once on board you had to bail out any water then get bounced around in the sea. If it was calm, the launches would come past at speed and create waves to simulate rough seas... a thoroughly enjoyable course to be honest. My next venture into the oggin was after a 2,000 ft parachute jump, thanks to Owen Connell!

Best regards

Arfur

Subject: Bob Pountney

Hi Tony,

In your e-mail you mentioned the helicopter winchman being Bob Pountney. I know him very well and had a dozen or so reunions and has stayed with me. Bob and his wife Maureen have a great air museum called Moravia up near Kinloss in Scotland. Has lots of planes and helicopters, as you would expect from him - kids get to climb all over them. Maybe you could give it a mention as a lot of lads might like to go to it:

https://www.morayvia.org.uk/

Best wishes

Joy Brown

(w/o Jim)

Subject: Prince Phillip exiting prototype Reliant Scimitar

Hi Tony,

Not sure if this has come up before, but I just watched a video on the internet on the Reliant Scimitar and they showed the attached picture of Prince Phillip exiting the prototype car and getting onto, I think, an RAF Comet. Just wondered if anybody knows if the RAF Flt Lt is a mover and his name?

Rgds

Dave Green

Subject: Survival Courses

Hi Tony;

After a few days of ground school, indoctrination, do's and don'ts of survival in the cold and cold weather kit issue at the Survival Training School at CFB Edmonton, we were bussed off to their training area (Jarvis Lake) just outside Hinton, Alberta.

The course there ran from 22 Jan to 04 Feb 1968. During that time the temperature was steady at -42ºF (in the good old days). Once there, we started out with a wooden platform, the roof was a parachute shroud, a wood heater in the corner and four men to make it happen for four days. Options suggested were 1 person up at all times to keep it warm or all sleep and let it get chilly!

At the same time we were taught how to build one-man lean-to's for our next sleeping area for four days, complete with log fire. From there we went into 2-men in the same lean-to. During the day we were taught how to:

1) How to build a fishing net, get it under the ice and make it work.

2) How to snare a rabbit and skin it to make a glove.

3) How to set up a bird snare (for use only in real survival situations).

4) How to build a signal smoke fire for the aircraft that would drop rations if they saw it.

Things I remember most were the "WHAT?" everybody said when told to undress before getting into the sleeping bag. At -42ºF that didn't seem right, but we did it.

If you had to enter The "Staff Cabin" because of an accident or illness you were CT'D and a ride home was arranged. The staff were great, the training was excellent, and the lessons I learned will always stay with me should I ever need them.

In closing I must mention the four one day ration packs we each had to make last the twelve days, because after all this was a survival training exercise.

On our last day on our way home we stopped at the restaurant in Hinton for breakfast and the instructors told us that of course our stomachs would be shrunk, and suggested that we have no more than a small glass of orange juice, one egg, one piece of toast and one cup of coffee. For those of us who listened and followed their advice we did just fine, but of course the "know it all" had to have a huge breakfast and shortly thereafter, before boarding the bus to head home, left it on the ground in the parking lot.

Thanks and cheers Tony!

Don.

to the Memories of:

Jim Brett (RAF)

Pete Mason (RNZAF)

Ron McMillan (RCAF)

Graeme McBride (RNZAF)

ukmamsoba@gmail.com