Boris Johnson Says VIP RAF Voyager 'Is Never Available'

From: Steve Harpum, York

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #042718

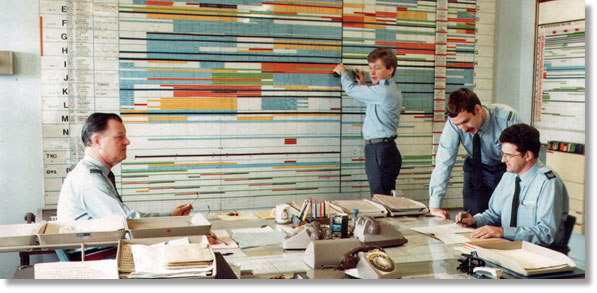

Many thanks, Tony - as ever, an interesting and enjoyable read, but I was literally brought to a halt by the picture of the UKMAMS Ops room. There sits the late, great Jim Stewart, of whom the stories are legion, and a certain (very, very young) Fg Off Andy Kime (and my sincere apologies to the other two gentlemen in the picture for forgetting their names). That picture was like stepping through a time warp for me, with so many happy memories coming flooding back.

I reckon that picture must have been taken in the early 1980's, but if you have any details I'd be very grateful.

Cheers, Steve

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #042718

Many thanks, Tony - as ever, an interesting and enjoyable read, but I was literally brought to a halt by the picture of the UKMAMS Ops room. There sits the late, great Jim Stewart, of whom the stories are legion, and a certain (very, very young) Fg Off Andy Kime (and my sincere apologies to the other two gentlemen in the picture for forgetting their names). That picture was like stepping through a time warp for me, with so many happy memories coming flooding back.

I reckon that picture must have been taken in the early 1980's, but if you have any details I'd be very grateful.

Cheers, Steve

From: Ian Berry, West Swindon

Subject: RE: Ops Photo

Tony/Steve,

With the aid of high resolution and a magnifying glass the picture was taken in June 1985. The two airmen in the picture are Sgt Ian Williams, last heard of as an employee of the Science Museum Reserve collection at Wroughton Airfield and SAC Chris Trevelyan whom when I last met in the 90's was a Bush Pilot flying the mail out of Seattle to inland Washington State.

Kindest regards,

Ian

Subject: RE: Ops Photo

Tony/Steve,

With the aid of high resolution and a magnifying glass the picture was taken in June 1985. The two airmen in the picture are Sgt Ian Williams, last heard of as an employee of the Science Museum Reserve collection at Wroughton Airfield and SAC Chris Trevelyan whom when I last met in the 90's was a Bush Pilot flying the mail out of Seattle to inland Washington State.

Kindest regards,

Ian

From: Alex Masson, Chelmsford, Essex

Subject: Memories of RAF Abingdon

Before we went to Christmas Island in 1956, Philip Pratley then a Corporal, and myself an SAC, went to Watchfield to join the 47 Company RASC (Royal Army Service Corps) to be taught how to despatch parachutes from transport aircraft. All of this was put into practice and we flew from Abingdon in the Hastings and Valetta aircraft of 1312 Flight and dropped our supplies on Watchfield.

Towards the end of the first week, one afternoon was to be a lecture by the CO, who was a Captain whose name I cannot now recall. He commenced by explaining that this lecture was most important, and went on to describe the ‘weight and balance’ of the cargo aeroplane, in this case the ‘Hastings’. He correctly drew our attention to the restrictive limits of the permissible ‘centre of gravity’ of the aircraft, which changes according to where the load is variously placed, and how it had to remain within these limits throughout take off, flight and ultimately the landing condition.

While this was intriguing stuff for some students, others, judging by the blank looks on some faces, clearly were completely baffled. To us, however, it was second nature as we had been loading these aeroplanes for almost two years.

I suppose I was getting a little bored with this as he wasn’t teaching us anything we did not know. My mind wandered and I was elsewhere when suddenly I was brought down to earth by something the Captain said. He was going through the mathematics of this aircraft load, putting a Landrover hard up front in a Hastings with some kind of small field gun up behind it with the trail of the gun snugly placed under the Landrover. I made a quick calculation and leaned over to Phil, who had been a little more awake than me, for he was scribbling furiously and he pre-empted me by saying, “Yes, it’s nose heavy!” I remarked “His figures are wrong.”

Next thing I was aware of the Captain bellowing at us telling us to be quiet and that he would not tolerate any talking or interruptions of his lecture. Before he had finished, I said, “Just a ‘cotton picking’ minute! Is that the entire load for that aircraft?” “Yes!” he snapped. I continued, “Then you are doing something wrong!” The Captain went into a rage. “Don’t tell me I’m wrong. I have here the official instructions ….” I interrupted him again saying, “I don’t know what you have there, but we load these planes every day of our working life and can see that something is badly wrong! If that is all the load then the plane will be nose heavy and well out of trim” Phil joined me, adding, “He’s right Sir! That plane will be nose heavy but at this moment I can’t for the life of me, see why.”

Gathering around the table, the Captain commenced, “Let’s start at the beginning, the basic empty weight of the Hastings is 41,689 lbs plus crew and standard equipment at 4,470 lbs gives us 46,159 lbs before load or fuel ….” We both broke in with “No way! Before fuel and load Hastings are between 53 and 54,000 lbs.” Then I saw on the top of the form ‘Hastings Mk1’. I said, “Good grief! There are no Mark 1’s flying in the RAF. They are all Mark 2’s or 1A’s.

Subject: Memories of RAF Abingdon

Before we went to Christmas Island in 1956, Philip Pratley then a Corporal, and myself an SAC, went to Watchfield to join the 47 Company RASC (Royal Army Service Corps) to be taught how to despatch parachutes from transport aircraft. All of this was put into practice and we flew from Abingdon in the Hastings and Valetta aircraft of 1312 Flight and dropped our supplies on Watchfield.

Towards the end of the first week, one afternoon was to be a lecture by the CO, who was a Captain whose name I cannot now recall. He commenced by explaining that this lecture was most important, and went on to describe the ‘weight and balance’ of the cargo aeroplane, in this case the ‘Hastings’. He correctly drew our attention to the restrictive limits of the permissible ‘centre of gravity’ of the aircraft, which changes according to where the load is variously placed, and how it had to remain within these limits throughout take off, flight and ultimately the landing condition.

While this was intriguing stuff for some students, others, judging by the blank looks on some faces, clearly were completely baffled. To us, however, it was second nature as we had been loading these aeroplanes for almost two years.

I suppose I was getting a little bored with this as he wasn’t teaching us anything we did not know. My mind wandered and I was elsewhere when suddenly I was brought down to earth by something the Captain said. He was going through the mathematics of this aircraft load, putting a Landrover hard up front in a Hastings with some kind of small field gun up behind it with the trail of the gun snugly placed under the Landrover. I made a quick calculation and leaned over to Phil, who had been a little more awake than me, for he was scribbling furiously and he pre-empted me by saying, “Yes, it’s nose heavy!” I remarked “His figures are wrong.”

Next thing I was aware of the Captain bellowing at us telling us to be quiet and that he would not tolerate any talking or interruptions of his lecture. Before he had finished, I said, “Just a ‘cotton picking’ minute! Is that the entire load for that aircraft?” “Yes!” he snapped. I continued, “Then you are doing something wrong!” The Captain went into a rage. “Don’t tell me I’m wrong. I have here the official instructions ….” I interrupted him again saying, “I don’t know what you have there, but we load these planes every day of our working life and can see that something is badly wrong! If that is all the load then the plane will be nose heavy and well out of trim” Phil joined me, adding, “He’s right Sir! That plane will be nose heavy but at this moment I can’t for the life of me, see why.”

Gathering around the table, the Captain commenced, “Let’s start at the beginning, the basic empty weight of the Hastings is 41,689 lbs plus crew and standard equipment at 4,470 lbs gives us 46,159 lbs before load or fuel ….” We both broke in with “No way! Before fuel and load Hastings are between 53 and 54,000 lbs.” Then I saw on the top of the form ‘Hastings Mk1’. I said, “Good grief! There are no Mark 1’s flying in the RAF. They are all Mark 2’s or 1A’s.

We then explained that there were no Mk1 aircraft in RAF Squadron service any more, they were all now modified up to Mk2 standard with bigger, heavier and more powerful engines. They had been re-designated Mk1A aircraft. This had altered the C of G limits. No wonder his calculations were wrong.

In due course we were called to re-assemble in the class. The Captain addressed us with, “I would like to express my appreciation to the RAF chaps here, who have drawn my attention to a fairly serious error. I would like to apologise for bawling at them for interrupting; I am more than pleased that they did.

"We have been instructing on an obsolete aircraft and we have never been updated as to what the RAF is currently using. Signals are, at this very moment going out to all trained staff to be aware of this fact, and arrangements are in hand for a re-training programme for all personnel to be initiated.”

The Captain, whose name escapes me, was greatly appreciative of our intervention, and spent a long time talking with us and finding out exactly what our job was in the RAF. For the remainder of the course we were consulted on all manner of procedures, just in case there were any other quirks in loading aeroplanes which could effect the efficiency of the training programme of 47 Company RASC.

One time, as we were loading some Landrovers in the mock-up of the Hastings, the RSM came up to see what we were doing. He paused by me and said, “You haven’t got that right!” I did see what he meant at first. He said, “Look here! You have not got that chain across the floor from here to there!” and he indicated with his ‘pace stick’ and he drew a line on the floor where it should be, behind the wheels of the Landrover.

Then I caught on, he had been looking at the plans but only from above, and had not realised that the chain was supposed to go over the axle of the vehicle. “I think it is better my way, the Landrover needs tying down, the Hasting floor does not!” He turned and disappeared.

"We have been instructing on an obsolete aircraft and we have never been updated as to what the RAF is currently using. Signals are, at this very moment going out to all trained staff to be aware of this fact, and arrangements are in hand for a re-training programme for all personnel to be initiated.”

The Captain, whose name escapes me, was greatly appreciative of our intervention, and spent a long time talking with us and finding out exactly what our job was in the RAF. For the remainder of the course we were consulted on all manner of procedures, just in case there were any other quirks in loading aeroplanes which could effect the efficiency of the training programme of 47 Company RASC.

One time, as we were loading some Landrovers in the mock-up of the Hastings, the RSM came up to see what we were doing. He paused by me and said, “You haven’t got that right!” I did see what he meant at first. He said, “Look here! You have not got that chain across the floor from here to there!” and he indicated with his ‘pace stick’ and he drew a line on the floor where it should be, behind the wheels of the Landrover.

Then I caught on, he had been looking at the plans but only from above, and had not realised that the chain was supposed to go over the axle of the vehicle. “I think it is better my way, the Landrover needs tying down, the Hasting floor does not!” He turned and disappeared.

Alex Masson, Philip Pratley - Abingdon,1956

Cheers,

Alex (and Legs!)

Alex (and Legs!)

From: Sam Mold, Brighton & Hove

Subject: Aden

To all RAF association newsletter editors listed on my computer, I'm sure several of your members would have survived a two-year stint to the barren rocks of Aden. I would be surprised to learn that anyone ever did two tours to this former colony, now a part of Yemen. A posting to the Suez Canal zone was not a popular posting, made even worse for unruly airmen who were punished with a posting to Aden for their troubles.

By the time my tour (1961-62) came round, massive improvements had been made with accommodation upgrades for airman and leasing modern flats in the Maala road for Married Quarters. The then Governor claimed this was the best street in the Arab world, and I don't think he was far wrong in his assessment.

There was a cold storage building in Steamer Point to keep fresh the meat and vegetables flown in from Kenya by RAF Beverley transport planes based at Khormaksar. My tour was neatly divided between the two RAF Stations: Steamer Point and Khomaksar. I enjoyed both of them; in fact, I liked Aden very much indeed. Some people find it hard to believe that I preferred my two-year tour in Aden more so than the 15-month tour served in Australia.

In its favour, Aden only has a couple of days rain a year, but more importantly, in those days, it is especially remembered as one of the cheapest places in the world. As a heavy 80-a-day smoker and a drinker who needed to replace sweat lost in the hot season when temperatures reached 120 degrees in the shade, made worse by 100% high humidity rates, it was essential to quench one's thirst. The day-to-day living expenses were so cheap that I can still recall prices. A pack of 200 king-size Rothmans cigarettes costs 9 shillings (45p); the same price as a bottle of spirits, other than the slightly more expensive brandy.

It would be nice to write a book about one of my favourite postings, but why bother when a book on the subject has already been written by someone much more clever than I could ever be.

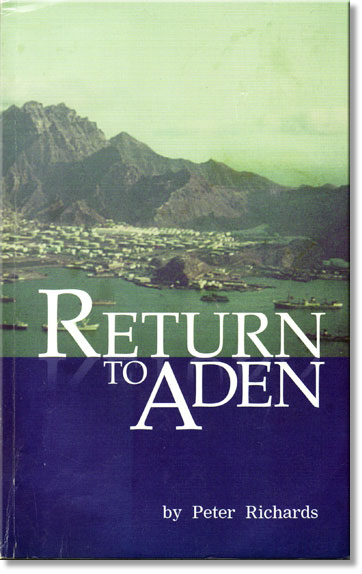

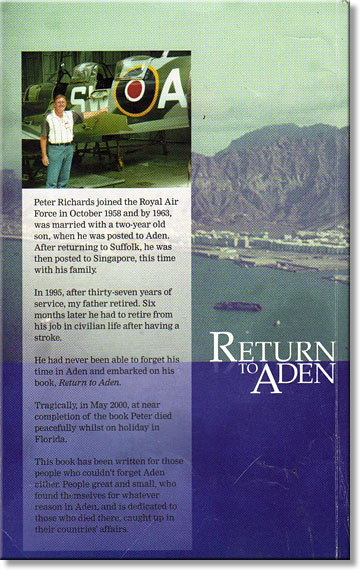

The late Peter Richards, a retired RAF engineering Warrant Officer, was writing a book, 'Return to Aden', but died before it had been completed. His two sons added the final two chapters and had the book published in 2004. It is a very comprehensive account and covers the full history of what once was a British Protectorate. I really enjoyed reading the book that turned out to be a wonderful memory-jogger. Names long forgotten came flying off the pages, reminding me of times long gone by. Anyone who has served in Aden, will, I'm sure, enjoy reading the book as much as I have.

Subject: Aden

To all RAF association newsletter editors listed on my computer, I'm sure several of your members would have survived a two-year stint to the barren rocks of Aden. I would be surprised to learn that anyone ever did two tours to this former colony, now a part of Yemen. A posting to the Suez Canal zone was not a popular posting, made even worse for unruly airmen who were punished with a posting to Aden for their troubles.

By the time my tour (1961-62) came round, massive improvements had been made with accommodation upgrades for airman and leasing modern flats in the Maala road for Married Quarters. The then Governor claimed this was the best street in the Arab world, and I don't think he was far wrong in his assessment.

There was a cold storage building in Steamer Point to keep fresh the meat and vegetables flown in from Kenya by RAF Beverley transport planes based at Khormaksar. My tour was neatly divided between the two RAF Stations: Steamer Point and Khomaksar. I enjoyed both of them; in fact, I liked Aden very much indeed. Some people find it hard to believe that I preferred my two-year tour in Aden more so than the 15-month tour served in Australia.

In its favour, Aden only has a couple of days rain a year, but more importantly, in those days, it is especially remembered as one of the cheapest places in the world. As a heavy 80-a-day smoker and a drinker who needed to replace sweat lost in the hot season when temperatures reached 120 degrees in the shade, made worse by 100% high humidity rates, it was essential to quench one's thirst. The day-to-day living expenses were so cheap that I can still recall prices. A pack of 200 king-size Rothmans cigarettes costs 9 shillings (45p); the same price as a bottle of spirits, other than the slightly more expensive brandy.

It would be nice to write a book about one of my favourite postings, but why bother when a book on the subject has already been written by someone much more clever than I could ever be.

The late Peter Richards, a retired RAF engineering Warrant Officer, was writing a book, 'Return to Aden', but died before it had been completed. His two sons added the final two chapters and had the book published in 2004. It is a very comprehensive account and covers the full history of what once was a British Protectorate. I really enjoyed reading the book that turned out to be a wonderful memory-jogger. Names long forgotten came flying off the pages, reminding me of times long gone by. Anyone who has served in Aden, will, I'm sure, enjoy reading the book as much as I have.

Those who wish to buy the book can obtain a copy by contacting Peter's widow: Mrs. Cherie Richards

Best wishes and happy hunting for 'Return to Aden' - Sam

Best wishes and happy hunting for 'Return to Aden' - Sam

NZDF's Mission in the Middle East off to a Flying Start

The New Zealand Defence Force’s (NZDF) air transport mission in the Middle East got off to a flying start this week, with the delivery of two tonnes of supplies for coalition troops operating in Iraq. The 32-strong detachment and a Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130H(NZ) Hercules aircraft are operating with the Australian Defence Force’s air mobility task group to transport supplies and personnel required for New Zealand, Australian and coalition operations in the Middle East region.

Squadron Leader Brad Scott, the Commander of the air transport team’s first rotation, said 30 New Zealand military personnel were also flown to Camp Taji in Iraq this week. “The entire team has been looking forward to this mission and to work once again with our Australian partners,” Squadron Leader Scott said. “Everyone is eager to get stuck in and show why we are regarded as a reliable and trusted coalition partner.” The detachment includes aircraft technicians, logistics specialists, maintenance personnel, and an Air Movements Load Team that will support coalition aircraft in the region.

Squadron Leader Brad Scott, the Commander of the air transport team’s first rotation, said 30 New Zealand military personnel were also flown to Camp Taji in Iraq this week. “The entire team has been looking forward to this mission and to work once again with our Australian partners,” Squadron Leader Scott said. “Everyone is eager to get stuck in and show why we are regarded as a reliable and trusted coalition partner.” The detachment includes aircraft technicians, logistics specialists, maintenance personnel, and an Air Movements Load Team that will support coalition aircraft in the region.

On a similar six-month deployment in 2016 an NZDF air transport mission transported nearly 800 tonnes of supplies and about 3200 military personnel to Iraq and Afghanistan. A month-long mission in 2017 transported 120 tonnes of supplies and about 500 personnel supporting coalition operations in the Middle East.

Medium.com

Medium.com

From: Jack Pyne, Wiltshire

Subject: Information on Sgt. Tony Pyne

Dear Mr Gale,

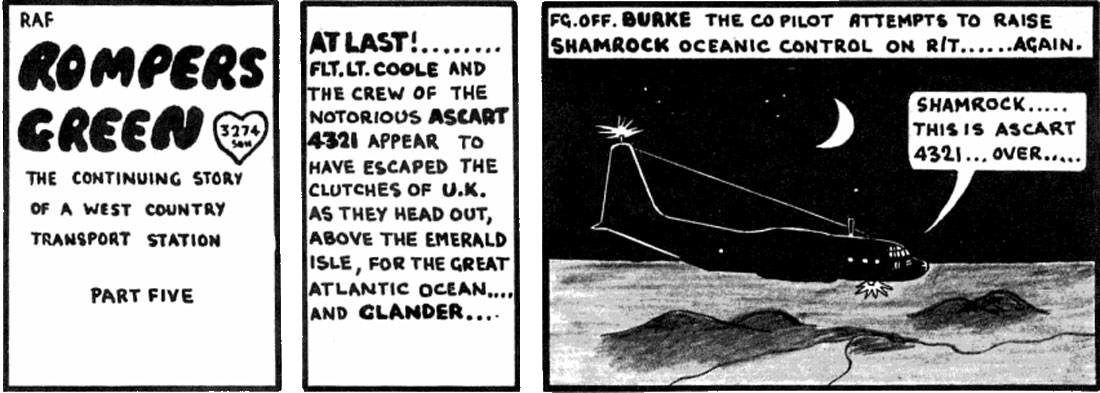

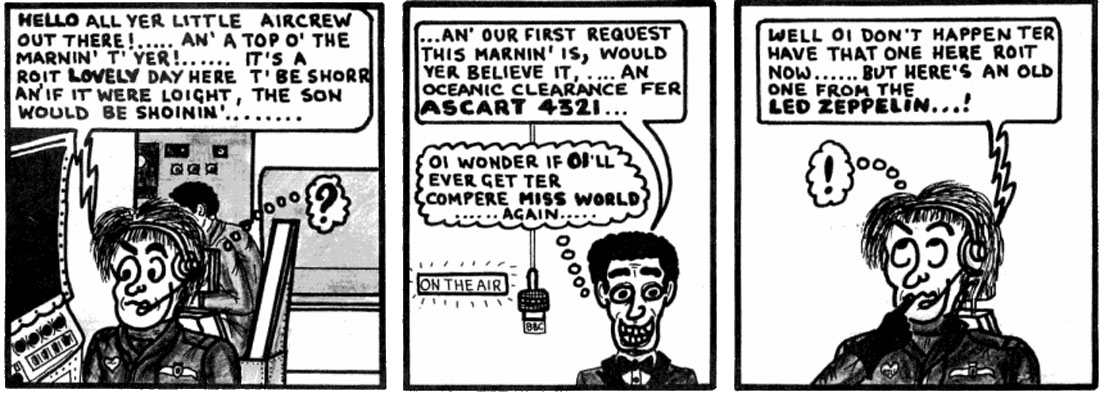

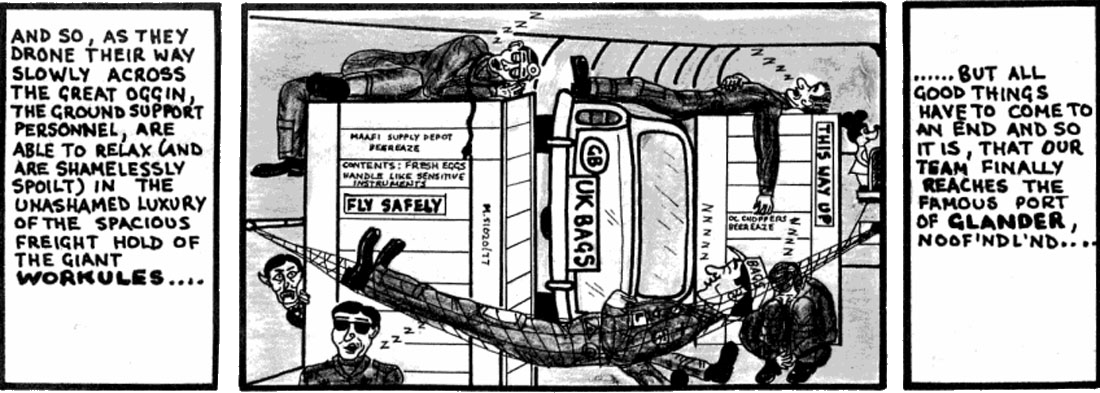

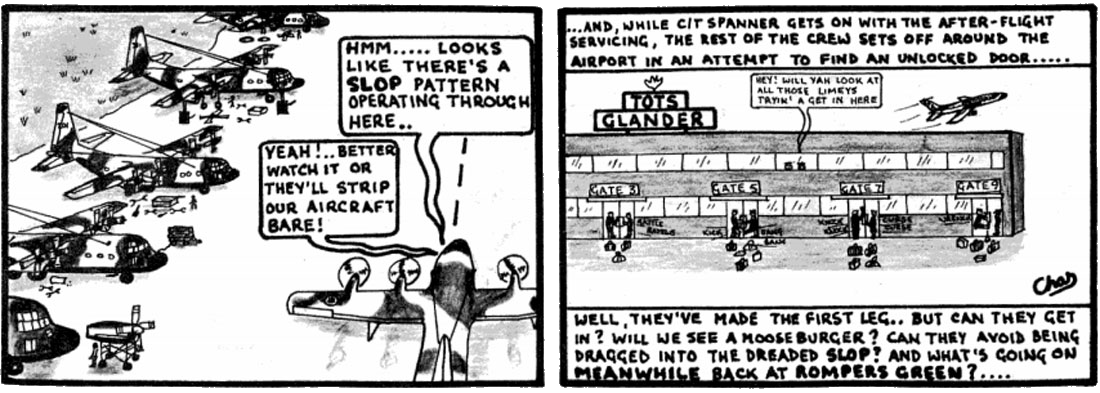

My name is Jack Pyne, I am 18 and don’t live too far away from RAF Lyneham. Sergeant Tony Pyne was my grandad, sadly he passed away last year. He was never too open about his time in the RAF and UKMAMS to my Nan, Dad or myself, all I know is that he was a very keen photographer and artist.

I gave him a quick search online and came across a couple of pictures of him and some of the old briefs on your site. I also saw that one of his former colleagues, Norman Radcliffe, had written a message on the site saying that he had a cartoon image that my grandad drew whilst he was serving. I searched Mr Radcliffe to see if I could get into contact with him, but sadly he too has passed away.

I was wondering if you had this cartoon or any other information or know of any places where I could find some of his cartoons, photos or anything on him?

I realise this is quite a strange request and completely out of the blue but any help would be massively appreciated as I try to find out about my grandad’s career.

Thank you for your time and I hope to hear from you sometime soon.

Jack Pyne,

Subject: Information on Sgt. Tony Pyne

Dear Mr Gale,

My name is Jack Pyne, I am 18 and don’t live too far away from RAF Lyneham. Sergeant Tony Pyne was my grandad, sadly he passed away last year. He was never too open about his time in the RAF and UKMAMS to my Nan, Dad or myself, all I know is that he was a very keen photographer and artist.

I gave him a quick search online and came across a couple of pictures of him and some of the old briefs on your site. I also saw that one of his former colleagues, Norman Radcliffe, had written a message on the site saying that he had a cartoon image that my grandad drew whilst he was serving. I searched Mr Radcliffe to see if I could get into contact with him, but sadly he too has passed away.

I was wondering if you had this cartoon or any other information or know of any places where I could find some of his cartoons, photos or anything on him?

I realise this is quite a strange request and completely out of the blue but any help would be massively appreciated as I try to find out about my grandad’s career.

Thank you for your time and I hope to hear from you sometime soon.

Jack Pyne,

From: Tony Gale, Gatineau, QC

Subject: Re: Information on Sgt. Tony Pyne

Dear Jack,

Thank you for your enquiry, although I was saddened to learn of your Grandfather's passing; please accept my belated condolences.

I did know Tony and indeed worked with him on several occasions. That was when the squadron was in its infancy back in the late 60's and early 70's at RAF Abingdon (now Dalton Barracks, a British Army base).

You will possibly have gleaned all the information and seen all the photographs that I have if you have performed a site search through the Google search bar at the bottom of the OBA home page.

I can do two things to perhaps aid you - firstly I'll place your e-mail into the upcoming monthly newsletter, due to be published on the 25th May, and secondly, I'll copy your e-mail directly to some surviving members of your Grandfather's former team, Alpha Team, in the hopes that someone out there can shed some light on the items you are looking for.

Here's looking forward to some responses!

Yours sincerely,

Tony Gale

Subject: Re: Information on Sgt. Tony Pyne

Dear Jack,

Thank you for your enquiry, although I was saddened to learn of your Grandfather's passing; please accept my belated condolences.

I did know Tony and indeed worked with him on several occasions. That was when the squadron was in its infancy back in the late 60's and early 70's at RAF Abingdon (now Dalton Barracks, a British Army base).

You will possibly have gleaned all the information and seen all the photographs that I have if you have performed a site search through the Google search bar at the bottom of the OBA home page.

I can do two things to perhaps aid you - firstly I'll place your e-mail into the upcoming monthly newsletter, due to be published on the 25th May, and secondly, I'll copy your e-mail directly to some surviving members of your Grandfather's former team, Alpha Team, in the hopes that someone out there can shed some light on the items you are looking for.

Here's looking forward to some responses!

Yours sincerely,

Tony Gale

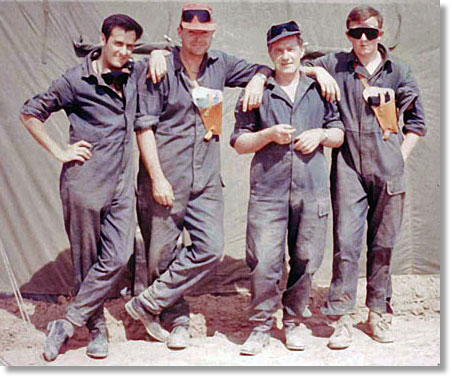

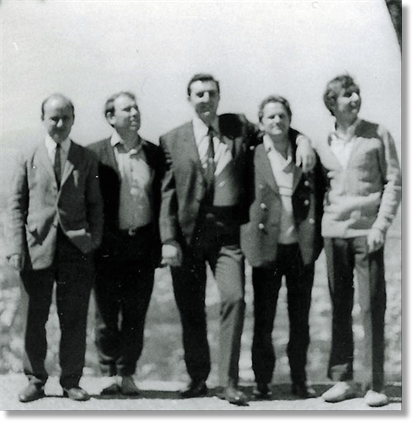

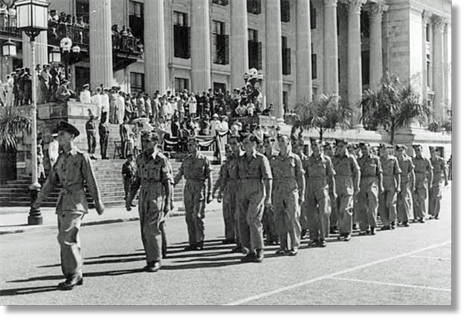

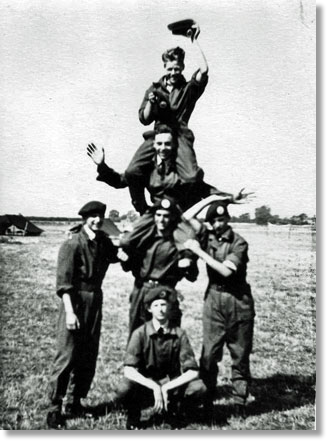

Alpha Team - Værløse, Denmark, 1969

Tony Pyne, Pete Spear, Alan "Boot" Pratt, John Evans, Jack Worrell (Eng) and Dave "Dizzy" Benson.

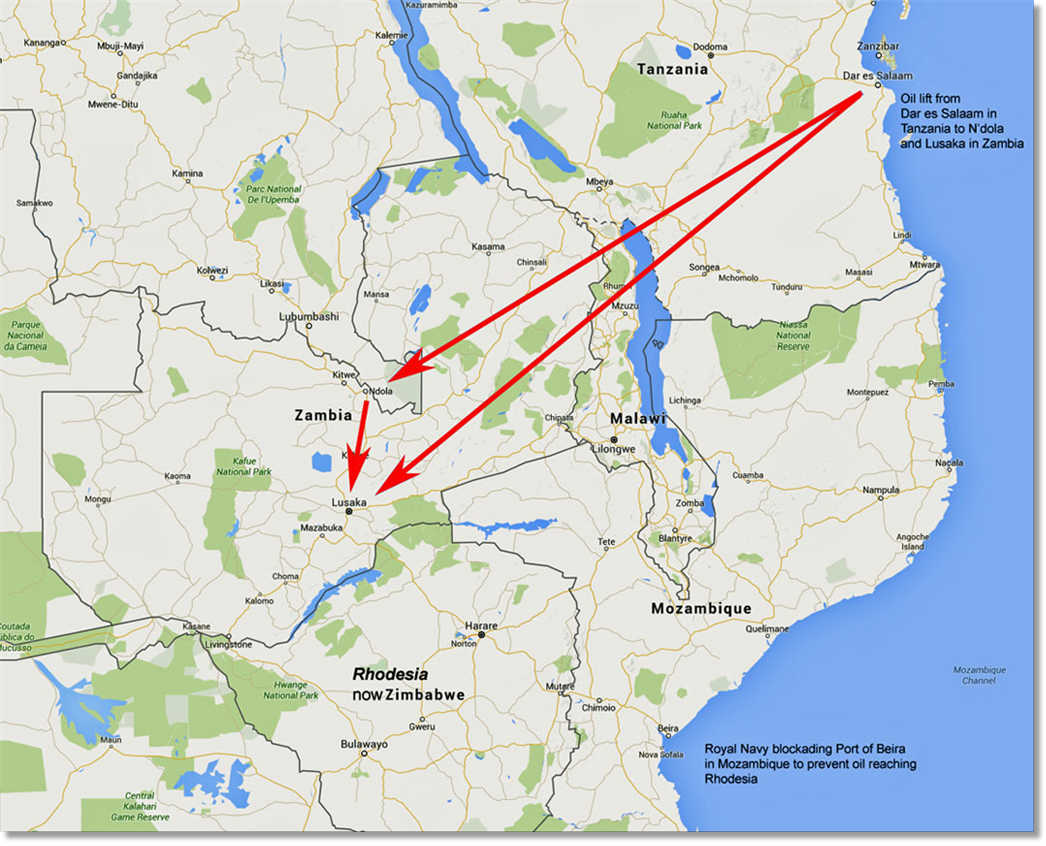

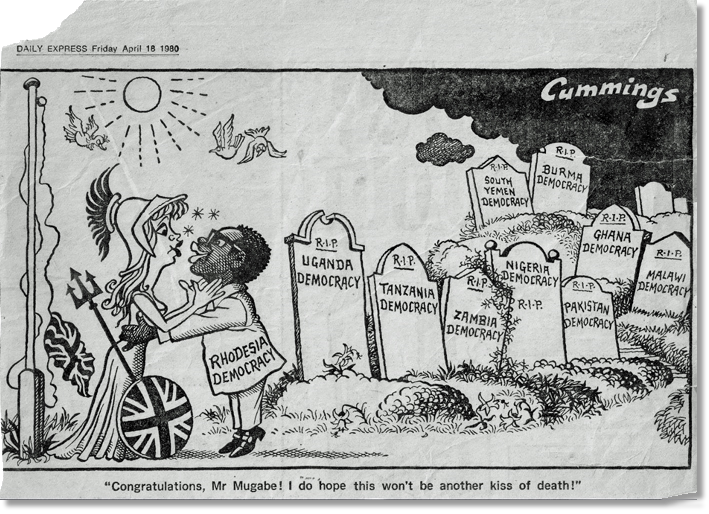

The Zambian Oil Lift

By Jeremy Porter with Photographs by Ian Stacey

By Jeremy Porter with Photographs by Ian Stacey

The whole operation began for UKMAMS on the 18th of December 1965, when a team departed RAF Abingdon for Dar Es Salaam (Tanzania) with five Britannia's of 99 and 511 Squadrons. Also on their way was a second team destined for Zambia where they would be staying in Lusaka. As far as the British press were concerned the MAMS team in Tanzania were accommodated in the recently finished Kilimanjaro Hotel, which was the pride and joy of the then President Julius Nyere. The harsh reality of life was slightly different for the down route team in Zambia - billeting for these unfortunates was achieved by taking over one wing of a local girls' boarding school.

As an insider will tell you, this sort of arrangement represents an absolute idyll for the average MAMS team. Sadly though, not everyone sees the arrangement through the same rose-coloured spectacles and becomes progressively less well appreciated by the other agencies involved as time goes on. Actually, the convoluted accommodation arrangements for both teams turned out to be slightly different from the standard bed and breakfast and the truth will emerge in its proper chronological order.

As an insider will tell you, this sort of arrangement represents an absolute idyll for the average MAMS team. Sadly though, not everyone sees the arrangement through the same rose-coloured spectacles and becomes progressively less well appreciated by the other agencies involved as time goes on. Actually, the convoluted accommodation arrangements for both teams turned out to be slightly different from the standard bed and breakfast and the truth will emerge in its proper chronological order.

The oil lift came into being as a result of an unstable political situation on the African continent (no surprises there). Zambia is a land-locked state and is therefore dependent on the ports and facilities of neighbouring states for its imports. It was hardly the fault of the Zambian Government that Rhodesia announced its unilateral declaration of independence which annoyed the United Nations sufficiently for them to impose sanctions on Ian Smith's regime. However, part of these sanctions involved the cutting off of oil supplies to Rhodesia, and this is where the problems started for Zambia. Most of Rhodesia's oil came into the country through a pipeline that started in the Mozambique ports where the tankers delivered it having sailed down from the Persian Gulf States. The pipeline, however, didn't terminate in Rhodesia but turned north and crossed into Zambia, feeding them with oil in the same manner as their neighbour. Cutting off the Rhodesians' oil meant turning off the supplies in Mozambique and therefore effectively cutting off the Zambians who, having voted for the sanctions, got justifiably annoyed at the subsequent effect on themselves.

The UN was faced with three options; the first was that they called off the oil sanction, but the UN was quite proud that it had got one of its few resolutions through a vote (quite a novelty) and was determined to see it through. The second option was to ask the Zambian Government to declare UDI as well, thus making them eligible to suffer sanctions, thereby justifying their plight. This however, met with an understandable lack of enthusiasm with the Zambian representatives at the UN and so was similarly discounted. The final option was to keep Zambia supplied whilst the Rhodesians suffered. This was the solution that the UN wanted to pursue, and the concept of the oil lift was born.

The UN was faced with three options; the first was that they called off the oil sanction, but the UN was quite proud that it had got one of its few resolutions through a vote (quite a novelty) and was determined to see it through. The second option was to ask the Zambian Government to declare UDI as well, thus making them eligible to suffer sanctions, thereby justifying their plight. This however, met with an understandable lack of enthusiasm with the Zambian representatives at the UN and so was similarly discounted. The final option was to keep Zambia supplied whilst the Rhodesians suffered. This was the solution that the UN wanted to pursue, and the concept of the oil lift was born.

Obviously, to run an airlift of such magnitude is an expensive proposition. Using the Britannia aircraft, each flight was able to carry around 2,250 gallons of fuel stores from Tanzania to Zambia, whilst the aircraft performing the service would, on its round trip, use approximately 2,700 gallons of fuel getting there and back. It was to be a trial of strength as to which side Rhodesia or "The Rest of The World" would suffer the most and give in first. Purists might venture the notion that in the event the Rhodesians seemed to continue to get oil supplies (almost certainly through South Africa) whilst many businesses in countries overtly supporting the sanctions continued to trade with Rhodesia (albeit slightly less overtly).

This policy is known to the economically inclined nations as commercial expediency, possibly because many politicians themselves have commercial interests. Few politicians are quite so active in the sporting sphere and so sportsmen of whatever persuasion would be tempting early retirement should they try the same tactic. The net result of the sanctions might, at the time, have been construed by the uncharitable as an expensive waste of time and money.

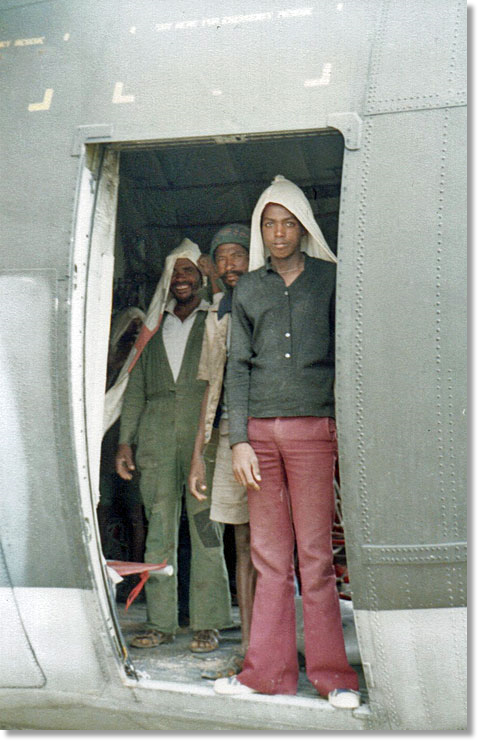

To ensure the airlift was to run smoothly and waste money in the most efficient manner, the teams established in Lusaka and Dar Es Salaam were to receive a small collection of aircraft handling aids. To achieve this, and before the airlift started, MAMS teams in Aden and Nairobi had been busy flying in the necessary heavy equipment previously held at their respective locations. Being traditionalists by nature, the UN stipulated that the oil lift should predominantly move loads of oil. Not surprisingly, the loads were in fact found to be fuel oil destined for both Zambian industry and transport. The operation was set up so that the teams in Dar Es Salaam received the oil from the refineries adjacent to the port, where it was decanted into 45 gallon oil drums. From here it was loaded to the RAF aircraft participating in the operation, flown from the airhead across to Zambia and landed in the capital's Lusaka airport. The team in Lusaka, led by Flying Officer Ian Stacey, would then offload the aircraft and distribute the drums to the authorities, where it was hoped that at least some of it would find its way into the legitimate economy. Other members of the team responsible for this included Sgts: Guthrie and Jim Balls, Cpls Chas Cormack and Brian Dunn, and SACs Roger Bullows and Jimmy Jamieson.

The daily lifts would start at first light and would last until dusk, with the aircraft stopping the nights at Dar Es Salaam. As each aircraft was scheduled to carry out two runs a day, the main bulk of the work was done at midday when the first flight returned and needed to be turned round for the second leg. At midday the temperature often climbed well above 100 Deg F and the humidity strived to join it.

The midday turnarounds were done against the clock, and involved the download of the inbound empty barrels from the Britannia, followed by the reload of the full barrels for the second trip. As there were no mad dogs available to do the work, Englishmen provided the main bulk of the workforce.

The outbound loads were comprised of an average of 50 forty-five gallon oil drums giving a payload of around 21,000 lbs. The drums were stacked in six stacks of eight barrels, with the balance reposing in the rear of the aircraft, depending on passengers to be carried.

Without the need to carry passengers, the aircraft could carry 52 drums, but for the loss of two drums up to four passengers could be flown with the load. As well as the barrels, the aircraft was literally festooned with wooden dunnage to protect the floor and stop the multitude of restraining chains from slipping off of the barrels. To help the team in their task, a freight lift platform was deployed from RAF Lyneham. Unfortunately, this particular piece of equipment had been recently the subject of an AOC's (Air Officer Commanding) inspection. It is one of the more glamorous duties of the AOC to inspect pieces of aircraft handling equipment and satisfy himself that all the nuts and bolts are painted bright red. This ensures that all the nuts and bolts are readily visible, but paradoxically almost impossible to move without paint stripper, a tin of WD 40, and a heavy duty torque wrench. This piece of equipment had sadly passed the inspection.

This policy is known to the economically inclined nations as commercial expediency, possibly because many politicians themselves have commercial interests. Few politicians are quite so active in the sporting sphere and so sportsmen of whatever persuasion would be tempting early retirement should they try the same tactic. The net result of the sanctions might, at the time, have been construed by the uncharitable as an expensive waste of time and money.

To ensure the airlift was to run smoothly and waste money in the most efficient manner, the teams established in Lusaka and Dar Es Salaam were to receive a small collection of aircraft handling aids. To achieve this, and before the airlift started, MAMS teams in Aden and Nairobi had been busy flying in the necessary heavy equipment previously held at their respective locations. Being traditionalists by nature, the UN stipulated that the oil lift should predominantly move loads of oil. Not surprisingly, the loads were in fact found to be fuel oil destined for both Zambian industry and transport. The operation was set up so that the teams in Dar Es Salaam received the oil from the refineries adjacent to the port, where it was decanted into 45 gallon oil drums. From here it was loaded to the RAF aircraft participating in the operation, flown from the airhead across to Zambia and landed in the capital's Lusaka airport. The team in Lusaka, led by Flying Officer Ian Stacey, would then offload the aircraft and distribute the drums to the authorities, where it was hoped that at least some of it would find its way into the legitimate economy. Other members of the team responsible for this included Sgts: Guthrie and Jim Balls, Cpls Chas Cormack and Brian Dunn, and SACs Roger Bullows and Jimmy Jamieson.

The daily lifts would start at first light and would last until dusk, with the aircraft stopping the nights at Dar Es Salaam. As each aircraft was scheduled to carry out two runs a day, the main bulk of the work was done at midday when the first flight returned and needed to be turned round for the second leg. At midday the temperature often climbed well above 100 Deg F and the humidity strived to join it.

The midday turnarounds were done against the clock, and involved the download of the inbound empty barrels from the Britannia, followed by the reload of the full barrels for the second trip. As there were no mad dogs available to do the work, Englishmen provided the main bulk of the workforce.

The outbound loads were comprised of an average of 50 forty-five gallon oil drums giving a payload of around 21,000 lbs. The drums were stacked in six stacks of eight barrels, with the balance reposing in the rear of the aircraft, depending on passengers to be carried.

Without the need to carry passengers, the aircraft could carry 52 drums, but for the loss of two drums up to four passengers could be flown with the load. As well as the barrels, the aircraft was literally festooned with wooden dunnage to protect the floor and stop the multitude of restraining chains from slipping off of the barrels. To help the team in their task, a freight lift platform was deployed from RAF Lyneham. Unfortunately, this particular piece of equipment had been recently the subject of an AOC's (Air Officer Commanding) inspection. It is one of the more glamorous duties of the AOC to inspect pieces of aircraft handling equipment and satisfy himself that all the nuts and bolts are painted bright red. This ensures that all the nuts and bolts are readily visible, but paradoxically almost impossible to move without paint stripper, a tin of WD 40, and a heavy duty torque wrench. This piece of equipment had sadly passed the inspection.

While the team wrestled with the platform, a forklift was recruited locally and was just robust enough to reach the sill height of the aircraft. Using this piece of kit, the loading of the barrels could commence while teams of stevedores struggled to undo the nuts on the platform.

As always, the team members were the very model of sartorial elegance and indulged in their strenuous activities clad in the finest raiment of tropical khaki. This early sort of KD had been specifically designed by the army and required heavy starching if it was to be even vaguely presentable. The reason for this was to catch out slipshod squaddies who tried to pass parade inspections by only pressing their uniform. This 'make it difficult' policy was actively pursued by the military during the sixties, although a further attempt at producing "stay-dull" dust attracting shoes was scrapped by the ministry owing to spiraling costs. So equipped with hard-to-manage uniforms, the teams went to work. The loading of oil drums onto aircraft is not the cleanest of professions and should not be recommended to those with a hyper-sensitive reaction to dirt. Not surprisingly, the work, coupled with the heat and humidity prevalent in the area, did little to improve the appearance of the unstarched UKMAMS team.

The appearance of the movers in the hotel foyer after a day's work did little to support the hotel's claim to a five star rating. This fact actually came to the attention of the President who summoned the detachment commander and re-briefed him on the statuesque and monumental magnificence of his hotel and the standards that the RAF were to maintain to avoid upsetting the other guests. The fact that the RAF detachment were in fact the only guests carried little weight and the detachment was duly obliged to modify its behavior.

To improve their appearance, the MAMS team had ties made bearing a strange motif of mushrooms and oil barrels arranged in diagonal rows on a green background. This design celebrated the fact that the team were now referred to as "mushroom airways" a result of being kept in the dark and fed on manure. On New Year's Eve, the UKMAMS team, mindful of their appearance and resplendent in new suits, were photographed by a local paper dancing in the New Year.

Once again, the President found the dress inappropriate which one might find a rather pedantic attitude were it not for the fact that the team, displaying an ingenious sense of protocol, were in the hotel swimming pool at the time. This time the detachment commander was summoned to the presence of the President again and, despite the best efforts of the diplomatic service, the team were evicted from both the hotel and the country.

Although this state of affairs might seem strange to a person cherishing a more traditional view of military experience, it is not uncommon for members of UKMAMS to be recruited by civilian companies they tend to come across during the course of their duties.

It is less common for their exit from RAF employment to be quite so contentious, many preferring to finish an engagement or purchase their exit before taking up with a more lucrative offer.

It has always been the case that civilian companies involved in transport or logistics tend to find that the members of professional movements organisations such as UKMAMS are particularly good value for money, having been trained and received considerable and diverse experience and all at the British taxpayers' expense.

Shortly after their unscheduled arrival in Kenya, the teams were due to be exchanged. This exchange was to take the form of a shuffle whereby the team in Lusaka were to return to UK to be replaced by the team from Kenya, who in turn would be replaced by a fresh team from the UK. The Lusaka team had been enjoying life a lot more than their up-route counterparts, for a start the working day was shorter and offloads are considerably easier than onloads. This, with the added bonus of staying in a girls' college, must have seemed an enviable attraction to Ian Stacey's team, who up until now had not been noted for their retiring sense of fun.

As always, the team members were the very model of sartorial elegance and indulged in their strenuous activities clad in the finest raiment of tropical khaki. This early sort of KD had been specifically designed by the army and required heavy starching if it was to be even vaguely presentable. The reason for this was to catch out slipshod squaddies who tried to pass parade inspections by only pressing their uniform. This 'make it difficult' policy was actively pursued by the military during the sixties, although a further attempt at producing "stay-dull" dust attracting shoes was scrapped by the ministry owing to spiraling costs. So equipped with hard-to-manage uniforms, the teams went to work. The loading of oil drums onto aircraft is not the cleanest of professions and should not be recommended to those with a hyper-sensitive reaction to dirt. Not surprisingly, the work, coupled with the heat and humidity prevalent in the area, did little to improve the appearance of the unstarched UKMAMS team.

The appearance of the movers in the hotel foyer after a day's work did little to support the hotel's claim to a five star rating. This fact actually came to the attention of the President who summoned the detachment commander and re-briefed him on the statuesque and monumental magnificence of his hotel and the standards that the RAF were to maintain to avoid upsetting the other guests. The fact that the RAF detachment were in fact the only guests carried little weight and the detachment was duly obliged to modify its behavior.

To improve their appearance, the MAMS team had ties made bearing a strange motif of mushrooms and oil barrels arranged in diagonal rows on a green background. This design celebrated the fact that the team were now referred to as "mushroom airways" a result of being kept in the dark and fed on manure. On New Year's Eve, the UKMAMS team, mindful of their appearance and resplendent in new suits, were photographed by a local paper dancing in the New Year.

Once again, the President found the dress inappropriate which one might find a rather pedantic attitude were it not for the fact that the team, displaying an ingenious sense of protocol, were in the hotel swimming pool at the time. This time the detachment commander was summoned to the presence of the President again and, despite the best efforts of the diplomatic service, the team were evicted from both the hotel and the country.

Although this state of affairs might seem strange to a person cherishing a more traditional view of military experience, it is not uncommon for members of UKMAMS to be recruited by civilian companies they tend to come across during the course of their duties.

It is less common for their exit from RAF employment to be quite so contentious, many preferring to finish an engagement or purchase their exit before taking up with a more lucrative offer.

It has always been the case that civilian companies involved in transport or logistics tend to find that the members of professional movements organisations such as UKMAMS are particularly good value for money, having been trained and received considerable and diverse experience and all at the British taxpayers' expense.

Shortly after their unscheduled arrival in Kenya, the teams were due to be exchanged. This exchange was to take the form of a shuffle whereby the team in Lusaka were to return to UK to be replaced by the team from Kenya, who in turn would be replaced by a fresh team from the UK. The Lusaka team had been enjoying life a lot more than their up-route counterparts, for a start the working day was shorter and offloads are considerably easier than onloads. This, with the added bonus of staying in a girls' college, must have seemed an enviable attraction to Ian Stacey's team, who up until now had not been noted for their retiring sense of fun.

As it was to turn out, the boys in Lusaka had really been doing their homework. Although most have declined to volunteer their names and experiences for publication, one of the original members, Mick McMahon, has broken silence to expose some of the exploits. It will therefore come as a great disappointment to those interested to learn that this account will not do likewise. Suffice to say that during the Operation, UKMAMS handled aircraft of Air Canada, BOAC, British Caledonian, Airbridge and Lloyd International, all with a great deal of not unprofitable professionalism.

The UKMAMS team were lucky to have among their number a man who could be described as an investment genius who, on behalf of his colleagues (and quite legally), managed to make the best use of the financial opportunities available. Working on the purest of socialist principles, all money received from the team's investments was used for the benefit of all who contributed. Such was the wisdom and foresight of this "financial security planning" that the UKMAMS team were quite literally able to live on the income without recourse to their hard-earned salary. With so much extra money available, Rest and Relaxation became a more attractive pastime.

To ensure that their members were to be refreshed for the next round of work, the MAMS team, using their investment returns, took out a long term let on a rather charming chalet on the shores of Lake Kariba. Travel to and from the chalet was by way of a minibus graciously donated to the team by a South African who was helping to distribute the fuel being flown into the country. By strange coincidence, the same man was able to ensure that the minibus remained topped up with petrol, although where he managed to find the stuff (which was closely controlled and rationed) will forever remain a mystery. The new team therefore arrived to a well set up operation and were looking forward to a prolonged stay in a girls' school. Unbeknown to Ian Stacey and his team, just before they arrived, the accommodation was changed, possibly as a result of over-fraternization with the locals with whom they were sharing.

The MAMS team found themselves evicted to a local showground, more commonly used and noted for the display of prize cattle. Also accommodated here were the rest of the detachment, which had been rapidly growing to some 400 strong. Most of the other inmates were RAF Regiment (rock apes), who were quite indistinguishable from the cattle that they had replaced and a detachment of Javelin aircraft plus their air and ground crews. This rather large cadre of personnel and equipment was intended as a deterrent against possible aggression against the transport forces conducting the airlift.

As can be imagined, bed spaces were at an absolute premium in the main show hall, with Rock Apes (named after one of their members historically did a rather good monkey impression whilst on holiday in Gibraltar) and pilots all fighting for the area of shallowest cow dung. The team down from Kenya arrived at a bit of a disadvantage, but as luck would have it the out-going team were sufficiently well placed in the affections of the building's owners to have been able to ensure that the VIP balcony over the main show ring was available for the exclusive use of UKMAMS. Not only was the balcony dung free, but it was also roomy and overlooked the main hall. One extra advantage of the balcony was that it had access to the main electrical fuse system for the whole hall. A popular pastime for the MAMS team continued to centre around the timely cancellation of all artificial light at intervals designed to create the maximum chaos for the hordes below attempting to bed down for the night whilst trying to avoid the cattle mess.

The work continued using both military and civil aircraft. BOAC were operating VC-1Os, which had both good capacity and payload. The team also turned round the Airbridge Corvairs which were slightly more limiting, but gave the MAMS team the opportunity of showing the civilians just how efficiently they could utilise the airframe, saving the company a considerable sum and gaining UKMAMS quite a bit of kudos. British Caledonian operated Britannia aircraft but as a standard passenger frame with the seats removed. Despite the unsuitability of the aircraft role fit, the MAMS teams were able to cram on board 40 drums of fuel which represented quite a respectable payload, but all of which had to be loaded through the passenger door.

The UKMAMS team were lucky to have among their number a man who could be described as an investment genius who, on behalf of his colleagues (and quite legally), managed to make the best use of the financial opportunities available. Working on the purest of socialist principles, all money received from the team's investments was used for the benefit of all who contributed. Such was the wisdom and foresight of this "financial security planning" that the UKMAMS team were quite literally able to live on the income without recourse to their hard-earned salary. With so much extra money available, Rest and Relaxation became a more attractive pastime.

To ensure that their members were to be refreshed for the next round of work, the MAMS team, using their investment returns, took out a long term let on a rather charming chalet on the shores of Lake Kariba. Travel to and from the chalet was by way of a minibus graciously donated to the team by a South African who was helping to distribute the fuel being flown into the country. By strange coincidence, the same man was able to ensure that the minibus remained topped up with petrol, although where he managed to find the stuff (which was closely controlled and rationed) will forever remain a mystery. The new team therefore arrived to a well set up operation and were looking forward to a prolonged stay in a girls' school. Unbeknown to Ian Stacey and his team, just before they arrived, the accommodation was changed, possibly as a result of over-fraternization with the locals with whom they were sharing.

The MAMS team found themselves evicted to a local showground, more commonly used and noted for the display of prize cattle. Also accommodated here were the rest of the detachment, which had been rapidly growing to some 400 strong. Most of the other inmates were RAF Regiment (rock apes), who were quite indistinguishable from the cattle that they had replaced and a detachment of Javelin aircraft plus their air and ground crews. This rather large cadre of personnel and equipment was intended as a deterrent against possible aggression against the transport forces conducting the airlift.

As can be imagined, bed spaces were at an absolute premium in the main show hall, with Rock Apes (named after one of their members historically did a rather good monkey impression whilst on holiday in Gibraltar) and pilots all fighting for the area of shallowest cow dung. The team down from Kenya arrived at a bit of a disadvantage, but as luck would have it the out-going team were sufficiently well placed in the affections of the building's owners to have been able to ensure that the VIP balcony over the main show ring was available for the exclusive use of UKMAMS. Not only was the balcony dung free, but it was also roomy and overlooked the main hall. One extra advantage of the balcony was that it had access to the main electrical fuse system for the whole hall. A popular pastime for the MAMS team continued to centre around the timely cancellation of all artificial light at intervals designed to create the maximum chaos for the hordes below attempting to bed down for the night whilst trying to avoid the cattle mess.

The work continued using both military and civil aircraft. BOAC were operating VC-1Os, which had both good capacity and payload. The team also turned round the Airbridge Corvairs which were slightly more limiting, but gave the MAMS team the opportunity of showing the civilians just how efficiently they could utilise the airframe, saving the company a considerable sum and gaining UKMAMS quite a bit of kudos. British Caledonian operated Britannia aircraft but as a standard passenger frame with the seats removed. Despite the unsuitability of the aircraft role fit, the MAMS teams were able to cram on board 40 drums of fuel which represented quite a respectable payload, but all of which had to be loaded through the passenger door.

By contrast, the Corvairs had a range payload performance which meant that only twenty eight drums could be moved at a time. Ironically, the Corvairs had a huge front door and lots of space, having been converted to carry short haul car traffic cross channel. The Royal Canadian Air Force also took part flying C-130s in from the Congo, 108 barrels at a time.

As all the additional units got involved the work, loading in Lusaka gradually crept up to cover the whole of the daylight hours. To keep traveling time to a minimum, UKMAMS acquired a caravan and a cooker that they managed to establish on the Embakasi airfield as a "mobile" crew room. Once again, the team seemed dogged by political problems and, having enjoyed a good few social beers in the airport bar with the local British expats, they were approached by a representation from the government and told that they would have to desist as they were there to help a black nation and not fraternize with the whites. I believe that an offer by the team to reoccupy the girls' college was not taken in the helpful vein in which it was intended and the Government shortly put the airport bar out of bounds. Golf suddenly became popular and MAMS took to patronising the local club and its nineteenth green facilities. Funnily enough, the same expats that used to occupy the airport bar were also keen golfers and so the dangerous liaison was able to continue.

As the Church is keen to make known, "helping others brings its own rewards" and by following a similar investment strategy as their predecessors, the UKMAMS team continued to flourish financially. To UKMAMS, the show ground now began to seem a little down market for people of their standing, although still quite suitable for the Pilots and Regiment personnel. It seemed that the time had come to move. The MAMS team sold their plot in the show ground and moved into a rented house just a stone's throw from a pub called the Pig and Whistle which inevitably became the local. Whilst here, they were visited by a base mover called Cpl Mick Moffatt who came down from Ndola which was occupied by another team of movers from the Air Force Middle East MAMS (a sister organisation to UKMAMS). A lively young man with an unconventional sense of humour when he went home, he took with him a smallish crocodile wrapped in wet cardboard.

Having successfully cleared customs on his return to UK thanks to there not being a question on the declaration form that covered crocodiles, Cpl Moffat deposited the reptile in the ornamental pond of a well-known local hotel. The crocodile remained undetected until the management drained the pool to find out why the ducks, so admired by the public, had been steadily disappearing despite constant restocking. If anyone recalls this incident from the papers, or any of the hotel management recognises the story, you now know the culprit. The crocodile was lucky enough to find refuge in London Zoo, which was its best alternative to being turned into a handbag.

The airlift ended for the civil airlines in July 1966 and the RAF finally pulled out in the following November. The moral of the whole airlift must be that if you are a duck on a pond in an hotel, and see a member of UKMAMS carrying a wet cardboard parcel, be sure you are "Swift to Move".

As a footnote, Charlie Cormack wrote the following in May 2001 regarding the chaps that went over the wall during the operation: The names you want for posterity are Geordie Davison, Dave Rossam and Fergie Ferguson who were all from MEAF MAMS at Dar Es Salaam at the beginning of the oil lift and their team leader was a P/O Wiblin (The Dreaded Piolt Office Wiblin - DPOW!) We had a session on new years eve 1965 in the Kilimanjaro Hotel in Dar Es Salaam, and whilst the aircrew were getting their pictures taken dancing in the pool in full evening dress, the movers were giving it some welly on the roof bar. It was at that stage that the three above mentioned expressed their intentions, as one minute they were going to be sent to Nairobi, and then they were told they were to go back to Aden to complete their tours. Geordie and Dave are still in South Africa to my knowledge, whilst Fergie "gave himself up " as his Mum was not very well and he was subsequently court martialled. His defending officer was one Sqn Ldr Don Clelland who got him off with 84 days and discharge but as he had already done a total very close to that number of days under open arrest, he never had to do any bird.

As all the additional units got involved the work, loading in Lusaka gradually crept up to cover the whole of the daylight hours. To keep traveling time to a minimum, UKMAMS acquired a caravan and a cooker that they managed to establish on the Embakasi airfield as a "mobile" crew room. Once again, the team seemed dogged by political problems and, having enjoyed a good few social beers in the airport bar with the local British expats, they were approached by a representation from the government and told that they would have to desist as they were there to help a black nation and not fraternize with the whites. I believe that an offer by the team to reoccupy the girls' college was not taken in the helpful vein in which it was intended and the Government shortly put the airport bar out of bounds. Golf suddenly became popular and MAMS took to patronising the local club and its nineteenth green facilities. Funnily enough, the same expats that used to occupy the airport bar were also keen golfers and so the dangerous liaison was able to continue.

As the Church is keen to make known, "helping others brings its own rewards" and by following a similar investment strategy as their predecessors, the UKMAMS team continued to flourish financially. To UKMAMS, the show ground now began to seem a little down market for people of their standing, although still quite suitable for the Pilots and Regiment personnel. It seemed that the time had come to move. The MAMS team sold their plot in the show ground and moved into a rented house just a stone's throw from a pub called the Pig and Whistle which inevitably became the local. Whilst here, they were visited by a base mover called Cpl Mick Moffatt who came down from Ndola which was occupied by another team of movers from the Air Force Middle East MAMS (a sister organisation to UKMAMS). A lively young man with an unconventional sense of humour when he went home, he took with him a smallish crocodile wrapped in wet cardboard.

Having successfully cleared customs on his return to UK thanks to there not being a question on the declaration form that covered crocodiles, Cpl Moffat deposited the reptile in the ornamental pond of a well-known local hotel. The crocodile remained undetected until the management drained the pool to find out why the ducks, so admired by the public, had been steadily disappearing despite constant restocking. If anyone recalls this incident from the papers, or any of the hotel management recognises the story, you now know the culprit. The crocodile was lucky enough to find refuge in London Zoo, which was its best alternative to being turned into a handbag.

The airlift ended for the civil airlines in July 1966 and the RAF finally pulled out in the following November. The moral of the whole airlift must be that if you are a duck on a pond in an hotel, and see a member of UKMAMS carrying a wet cardboard parcel, be sure you are "Swift to Move".

As a footnote, Charlie Cormack wrote the following in May 2001 regarding the chaps that went over the wall during the operation: The names you want for posterity are Geordie Davison, Dave Rossam and Fergie Ferguson who were all from MEAF MAMS at Dar Es Salaam at the beginning of the oil lift and their team leader was a P/O Wiblin (The Dreaded Piolt Office Wiblin - DPOW!) We had a session on new years eve 1965 in the Kilimanjaro Hotel in Dar Es Salaam, and whilst the aircrew were getting their pictures taken dancing in the pool in full evening dress, the movers were giving it some welly on the roof bar. It was at that stage that the three above mentioned expressed their intentions, as one minute they were going to be sent to Nairobi, and then they were told they were to go back to Aden to complete their tours. Geordie and Dave are still in South Africa to my knowledge, whilst Fergie "gave himself up " as his Mum was not very well and he was subsequently court martialled. His defending officer was one Sqn Ldr Don Clelland who got him off with 84 days and discharge but as he had already done a total very close to that number of days under open arrest, he never had to do any bird.

Chas Cormack and Brian Dunn on a British Caledonian Britannia back-loading empties for Dar-Es-Salaam

Having completed the back-load, Brian Dunn walks away from the British Caledonian Britannia, which will soon depart for Dar Es Salaam.

These aircraft were difficult to work with as there was no cargo door and all loads had to be manhandled through the passenger doors.

These aircraft were difficult to work with as there was no cargo door and all loads had to be manhandled through the passenger doors.

Embakazi Airport - the very first Short Belfast on air trials was roped in to help out. There's a civilian G-XXXX registration number on her which cannot be made out. A UKMAMS Landrover is behind the GPU in the foreground.

Embakazi Airport, Nairobi - a stockpile of fuel oil awaits to be allocated to transport aircraft for onmove to Zambia

Embakazi - drums of fuel oil being rolled across the tarmac towards a waiting RAF Britannia where they will be loaded to the aircraft with the aid of the Britannia Freight Lift Platform (BFLP).

As the sun rises over the African landscape, a Britannia awaits in the relative coolness of the dawn for the work day to commence.

Some down time for the boys - Roger Bullows and Chas Cormack on the lake above the Kariba Dam in the Kariba Gorge of the Zambezi river basin between Zambia and Rhodesia

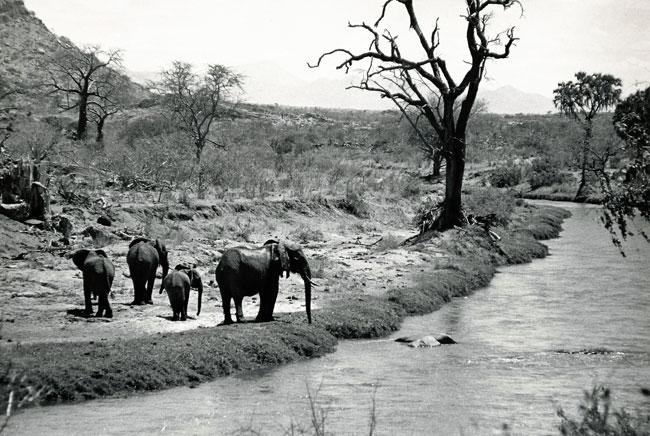

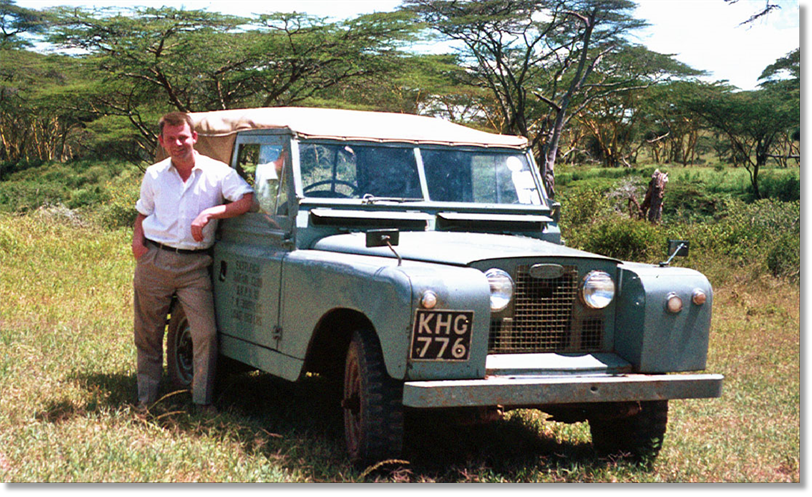

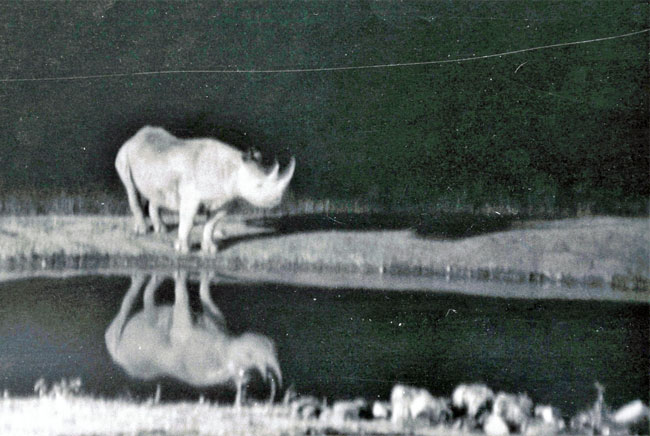

Graham Morgan - one of the original UKMAMS Team Leaders - in the Game Reserve

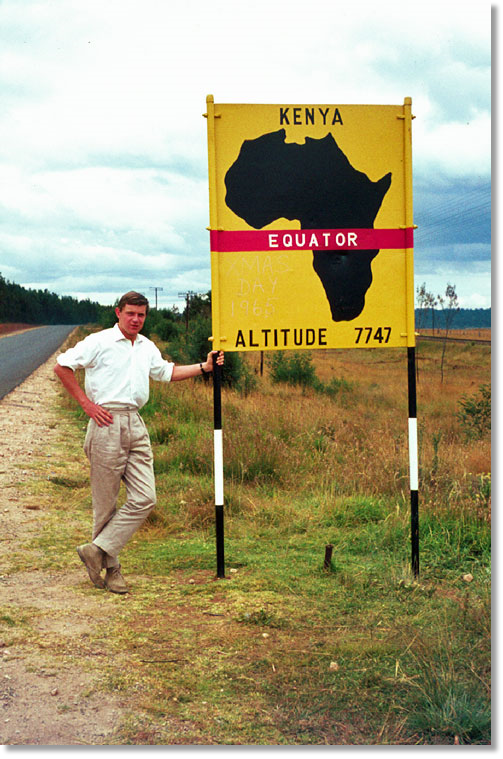

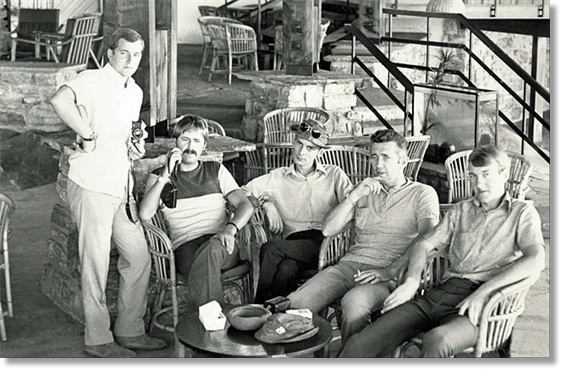

Xmas Day 1965 - Ian Stacey, another original team leader.

The motley crew of Movers, mostly Delta team UKMAMS: Jim Guthrie, Roger Bullows, Ian Stacey, Charlie Cormack, Brian Dunn, Jimmy Jamieson and Jim Balls.

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central African Republic

Chad

Democratic Republic of Congo

Republic of Congo

Cote d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central African Republic

Chad

Democratic Republic of Congo

Republic of Congo

Cote d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Reunion

Rwanda

Sao Tome and Principe

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Reunion

Rwanda

Sao Tome and Principe

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Zambia

Zimbabwe

From: Gerry Davis, Bedminster, Somerset

Subject: Africa

My stint on the Oil Lift 1966

Subject: Africa

My stint on the Oil Lift 1966

There is no sound on this video. The last scene shows the Kariba Dam.

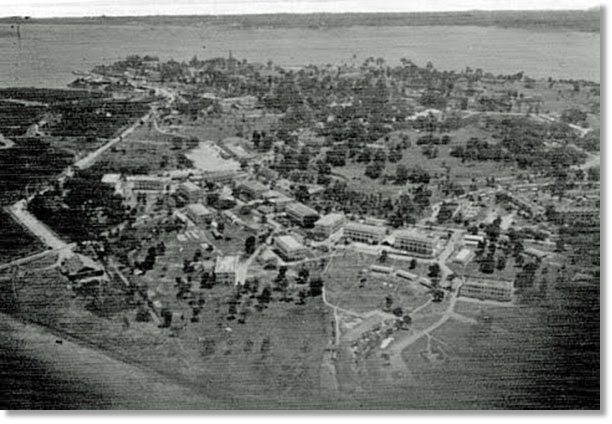

When the Oil Lift first got underway in December 1965, UKMAMS operated from an airfield at Dar-es-Salaam in Tanzania, but this caused masses of diplomatic upheaval, so some teams were dispatched to the civil airport at Embakasi in Nairobi, while other teams were sent to both Lusaka and Ndola in Zambia.

Part One - In early January 1966, I was on NEAF MAMS at Akrotiri in Cyprus and was tasked with my team to the Oil Lift. When we arrived in Nairobi, we were accommodated in the Kenyan Air Force billets at RAF Eastleigh until they wanted their billets back because of a large recruitment drive. So from then onwards we dossed down at the Spread Eagle Hotel situated on the outskirts of Nairobi; what a place! All of the small rooms, two beds per, were on the ground floor. Throughout both of my three-month detachments at this place there was a lot of thieving by the African locals taking place.

Part One - In early January 1966, I was on NEAF MAMS at Akrotiri in Cyprus and was tasked with my team to the Oil Lift. When we arrived in Nairobi, we were accommodated in the Kenyan Air Force billets at RAF Eastleigh until they wanted their billets back because of a large recruitment drive. So from then onwards we dossed down at the Spread Eagle Hotel situated on the outskirts of Nairobi; what a place! All of the small rooms, two beds per, were on the ground floor. Throughout both of my three-month detachments at this place there was a lot of thieving by the African locals taking place.

At work we had six RAF Britannia aircraft to play with. Well it eventually settled down to that, as initially all sorts of civilian charter aircraft were commandeered to assist with what we were there for. This was to ferry gasoline to the Zambian airfields of Lusaka and Ndola. The fuel was in 44 gallon drums, 56 of which were loaded into each aircraft which were then chained down to the aircraft floor. It was a lot of heavy work.

The Javelin jet fighters from our base in Cyprus were also dispatched to the Zambian airfields as fighter protection. Before they left Cyprus they all had to be re-painted as they were nearing the end of their shelf life and no two looked alike.

We had 12 African labourers allocated to two 12 hour shifts to help us with all the physical work. Most of them were excellent workers, although one or two did get the chop for various reasons, mostly for not turning up for work. They got paid fortnightly and after getting their hands on the dosh they promptly spent it on booze or paying off loans and were usually skint the following day; their ladies never saw any of it.

The Javelin jet fighters from our base in Cyprus were also dispatched to the Zambian airfields as fighter protection. Before they left Cyprus they all had to be re-painted as they were nearing the end of their shelf life and no two looked alike.

We had 12 African labourers allocated to two 12 hour shifts to help us with all the physical work. Most of them were excellent workers, although one or two did get the chop for various reasons, mostly for not turning up for work. They got paid fortnightly and after getting their hands on the dosh they promptly spent it on booze or paying off loans and were usually skint the following day; their ladies never saw any of it.

I remember one of the African workers telling me that his woman was sick. As I had a packet of Aspirin in my nav bag, I gave them to him. The look on his face was amazing, he was really grateful. Mind you, I don’t know if he ever gave them to her.

The whole detachment of Air Movers and Techies upset the newly appointed Kenyan airport chief security officer. He objected to our apparel, in that we were mostly scruffy as hell and didn’t take any notice of him when he came strutting around. Amongst other things he did not like us doing was eating dressed like this in the airport terminal restaurant or hanging around the arrivals hall oggling all the air hostesses and female passengers. As a result of his intervention from then on we had to dine in the staff canteen.

There was an attempt at using another form of fuel container other than the oil drums on the Britannias. It was a large round rubber ball with a capacity of around 400 gallons and had ‘D’ rings attached on both sides. Following a short trial period they were abandoned as they kept leaking when pressure was applied to the ‘D’ rings from the chains securing them to the aircraft floor. After three months, the other NEAF MAMS team came out to relieve us and do their stint loading all those 44 gallon drums of gasoline. So now we could make our way back to Cyprus.

Part Two - Three months break from the perpetual oil drums passed far too quickly and we took up residence in the Spread Eagle Hotel once more. The six Britannia aircraft were each still doing two sorties a day, loaded with 56 forty-five gallon drums of aviation gasoline flying between 0500 hours and 2200 hours.

On their return flights to Embakasi they often brought back ninety empty drums from Lusaka and Ndola, although the majority of the empty drums were transported overland. The vehicles used were large Fiat lorries with trailers. These vehicles transversed the jungle tracks which often had to be made as they drove along. When it rained they often got stuck in the mud, with African drivers helping each other to get unstuck. On arrival the drums were then checked to see if they were still suitable for air transportation, if they were they were refilled.

Time off was spent exploring the pleasures of the Kenyan capital. Those of us who had a taste for some ale soon developed a liking for the local brew of ‘Tusker’ beer. You honestly had to down gallons of the stuff to dull the effects of those barrels of oil and get rid of the stink of fuel.

One thing worth a mention, on one of our day’s off, three of us decided to partake in a mission to find an Italian nosh house; I really fancied a spaghetti bolognaise. So there we were ambling down Jomo Kenyatta Avenue in Nairobi with our sergeant in the middle, when a young gorgeous English lady hopped right in front of our already red-faced SNCO placing her hand on his chest and in a very sexy voice asking him, “Would you like to come to my flat and listen to music for the afternoon?” The look on his face sort of indicated an imminent heart attack. He spluttered out something to the effect that he was in a hurry and had to get back to work. Well I never, and he was single too! At this time the film “Cowboys in Africa” was being made and we often saw some of the stars relaxing in the Thorn Tree Café of the New Stanley Hotel.

The whole detachment of Air Movers and Techies upset the newly appointed Kenyan airport chief security officer. He objected to our apparel, in that we were mostly scruffy as hell and didn’t take any notice of him when he came strutting around. Amongst other things he did not like us doing was eating dressed like this in the airport terminal restaurant or hanging around the arrivals hall oggling all the air hostesses and female passengers. As a result of his intervention from then on we had to dine in the staff canteen.

There was an attempt at using another form of fuel container other than the oil drums on the Britannias. It was a large round rubber ball with a capacity of around 400 gallons and had ‘D’ rings attached on both sides. Following a short trial period they were abandoned as they kept leaking when pressure was applied to the ‘D’ rings from the chains securing them to the aircraft floor. After three months, the other NEAF MAMS team came out to relieve us and do their stint loading all those 44 gallon drums of gasoline. So now we could make our way back to Cyprus.

Part Two - Three months break from the perpetual oil drums passed far too quickly and we took up residence in the Spread Eagle Hotel once more. The six Britannia aircraft were each still doing two sorties a day, loaded with 56 forty-five gallon drums of aviation gasoline flying between 0500 hours and 2200 hours.

On their return flights to Embakasi they often brought back ninety empty drums from Lusaka and Ndola, although the majority of the empty drums were transported overland. The vehicles used were large Fiat lorries with trailers. These vehicles transversed the jungle tracks which often had to be made as they drove along. When it rained they often got stuck in the mud, with African drivers helping each other to get unstuck. On arrival the drums were then checked to see if they were still suitable for air transportation, if they were they were refilled.

Time off was spent exploring the pleasures of the Kenyan capital. Those of us who had a taste for some ale soon developed a liking for the local brew of ‘Tusker’ beer. You honestly had to down gallons of the stuff to dull the effects of those barrels of oil and get rid of the stink of fuel.

One thing worth a mention, on one of our day’s off, three of us decided to partake in a mission to find an Italian nosh house; I really fancied a spaghetti bolognaise. So there we were ambling down Jomo Kenyatta Avenue in Nairobi with our sergeant in the middle, when a young gorgeous English lady hopped right in front of our already red-faced SNCO placing her hand on his chest and in a very sexy voice asking him, “Would you like to come to my flat and listen to music for the afternoon?” The look on his face sort of indicated an imminent heart attack. He spluttered out something to the effect that he was in a hurry and had to get back to work. Well I never, and he was single too! At this time the film “Cowboys in Africa” was being made and we often saw some of the stars relaxing in the Thorn Tree Café of the New Stanley Hotel.

Another often visited place between shifts was the large market, nearly all the stalls and the shops were owned by the large Indian merchant classes. This is of course before the mass exodus from Kenya, as a result of all the Asians being affected by the new laws brought in 1968 forbidding them to own businesses.

I bought several wooden carvings and some decent books. Back at our Hotel I haggled with one of the African wood carvers for a couple of days for a two foot high carving of a Massai warrior standing on one leg holding a spear and a shield. It was stained to look like ebony, which he professed it was. Anyway he eventually settled for the equivalent of £2. This carving takes pride of place in our living room even today.

As the corporal on the team, I was the only one who had a defined job to carry out. I was responsible for all the paperwork, the driving of the specialist vehicles and trimming the aircraft. On the Oil Lift this also meant driving the 12,000 lb, forklift, operating the lift platform, loading and helping to tie down the barrels of gasoline. There was a standard method of chaining these barrels down to the aircraft floor. The paper work consisted of freight and passenger manifests, six copies of each. There was also a F.Sigs 52 to be sent to the forward airfield and command HQ informing them of the aircraft loads. All the RAF aircraft had a separate trim sheet; all of these documents were very large, consisting of three different coloured copies, with duplicating paper in between. On these forms a graph was drawn, indicating the position, by weight of the loads in marked areas of the freight bay. At the bottom of the forms was a box which the trimming of the aircraft was to fall within, for the aircraft to fly safely. Quite a lot to do within the turn round time, so that the flight schedules could be met.

Another three months passed and it was back to Cyprus.

I bought several wooden carvings and some decent books. Back at our Hotel I haggled with one of the African wood carvers for a couple of days for a two foot high carving of a Massai warrior standing on one leg holding a spear and a shield. It was stained to look like ebony, which he professed it was. Anyway he eventually settled for the equivalent of £2. This carving takes pride of place in our living room even today.

As the corporal on the team, I was the only one who had a defined job to carry out. I was responsible for all the paperwork, the driving of the specialist vehicles and trimming the aircraft. On the Oil Lift this also meant driving the 12,000 lb, forklift, operating the lift platform, loading and helping to tie down the barrels of gasoline. There was a standard method of chaining these barrels down to the aircraft floor. The paper work consisted of freight and passenger manifests, six copies of each. There was also a F.Sigs 52 to be sent to the forward airfield and command HQ informing them of the aircraft loads. All the RAF aircraft had a separate trim sheet; all of these documents were very large, consisting of three different coloured copies, with duplicating paper in between. On these forms a graph was drawn, indicating the position, by weight of the loads in marked areas of the freight bay. At the bottom of the forms was a box which the trimming of the aircraft was to fall within, for the aircraft to fly safely. Quite a lot to do within the turn round time, so that the flight schedules could be met.

Another three months passed and it was back to Cyprus.

From: Tony Street, Buffalo, NY

Subject: Africa

The Number One Bar

Subject: Africa

The Number One Bar