The Airbus CC-295 Kingfisher takes on SAR alert at Comox

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) retired its last CC-115 Buffalo aircraft from operational service with No.442 Squadron, leaving something of a gap in Canada’s Search and Rescue capability. Delays in the certification of the replacement CC-295 saw two SAR-equipped C-130H Hercules being deployed from Greenwood (Nova Scotia), Trenton (Ontario), or Winnipeg (Manitoba) to Comox to provide interim SAR coverage for the West Coast and Rocky Mountains. These returned to their home bases in January.

Meanwhile, the introduction of the CC-295 into Canadian service was overseen by No.418 Squadron at Comox.

The CC-295 Kingfisher officially became the fixed-wing SAR response aircraft at No.442 Squadron, starting on 1 May 2025, ready to respond on a 24/7 basis, 365 days a year.

Canada ordered sixteen CC-295 Kingfishers from Airbus, and ten of these have now been delivered, (plus a ground instructional airframe, serial 295517). The CC-295 is expected to gradually take over SAR duties at Greenwood, Trenton, and Winnipeg, replacing the last SAR-equiped C-130H Hercules.

aerospaceglobalnews

Meanwhile, the introduction of the CC-295 into Canadian service was overseen by No.418 Squadron at Comox.

The CC-295 Kingfisher officially became the fixed-wing SAR response aircraft at No.442 Squadron, starting on 1 May 2025, ready to respond on a 24/7 basis, 365 days a year.

Canada ordered sixteen CC-295 Kingfishers from Airbus, and ten of these have now been delivered, (plus a ground instructional airframe, serial 295517). The CC-295 is expected to gradually take over SAR duties at Greenwood, Trenton, and Winnipeg, replacing the last SAR-equiped C-130H Hercules.

aerospaceglobalnews

From: Tony Street, Fort Erie, ON

Subject: Survival Exercise

Hi Tony,

Many moons ago, when I was a Loadie on 437 Sqn, Trenton, ON, we flew on the CC106 Yukon (Canadair CC44, a large a/c that could hold 125 Pax). When we carried pax, and we had to serve meals; we had two female flight attendants and a LM in the cabin.

One day, our boss decided we need to have a ditching drill to give us a real experience, just in case. As we were based beside Lake Ontario, water was not hard to find. About 12 of us, Loadies and Flight Attendants, boarded a rescue boat and were taken to deep water (if you can't touch bottom it doesn't matter how deep it is), where, wearing Mae Wests, we threw ourselves into the lake. The rescue boat then made a pass by us and threw a 20 Man life raft into our midst. It inflated instantly. Now what?

We were clinging to the side of the raft figuring out the next step. There was a group of us at each boarding door as we dealt with the boarding issue. As there was a male closest to the entrance, he started climbing up the ladder and found, as we all did, stepping onto the bottom rung of the ladder, your weight caused the ladder to swing under the raft at a 45º angle with your back facing down. As we were not filled with adrenaline as we would have been, most of us did not have enough strength to climb aboard. Finally one man did, thus a few of us were able to rescue ourselves. The next in line were a couple of FAs who, not having the strength, also had difficulty with the problem. It was decided the guy in the raft would lean out of the raft and, grabbing each other's wrists, haul the FAs into the raft, it didn't work, he almost fell out. Then one of the guys tried to help by grabbing her lower legs and giving her a boost. As they were both flapping around in the water, his hand slipped upward and came in touch with her lady part. She quickly had an adrenaline rush. Voila! The other FA found her own adrenaline and the exercise was finished; it was never repeated.

Best regards,

Tony

Subject: Survival Exercise

Hi Tony,

Many moons ago, when I was a Loadie on 437 Sqn, Trenton, ON, we flew on the CC106 Yukon (Canadair CC44, a large a/c that could hold 125 Pax). When we carried pax, and we had to serve meals; we had two female flight attendants and a LM in the cabin.

One day, our boss decided we need to have a ditching drill to give us a real experience, just in case. As we were based beside Lake Ontario, water was not hard to find. About 12 of us, Loadies and Flight Attendants, boarded a rescue boat and were taken to deep water (if you can't touch bottom it doesn't matter how deep it is), where, wearing Mae Wests, we threw ourselves into the lake. The rescue boat then made a pass by us and threw a 20 Man life raft into our midst. It inflated instantly. Now what?

We were clinging to the side of the raft figuring out the next step. There was a group of us at each boarding door as we dealt with the boarding issue. As there was a male closest to the entrance, he started climbing up the ladder and found, as we all did, stepping onto the bottom rung of the ladder, your weight caused the ladder to swing under the raft at a 45º angle with your back facing down. As we were not filled with adrenaline as we would have been, most of us did not have enough strength to climb aboard. Finally one man did, thus a few of us were able to rescue ourselves. The next in line were a couple of FAs who, not having the strength, also had difficulty with the problem. It was decided the guy in the raft would lean out of the raft and, grabbing each other's wrists, haul the FAs into the raft, it didn't work, he almost fell out. Then one of the guys tried to help by grabbing her lower legs and giving her a boost. As they were both flapping around in the water, his hand slipped upward and came in touch with her lady part. She quickly had an adrenaline rush. Voila! The other FA found her own adrenaline and the exercise was finished; it was never repeated.

Best regards,

Tony

From: Graham Grice

Subject: Facebook Entry

Hello Tony,

Many thanks for the latest edition of the OBA newsletter. A fascinating read.

Ron Turley’s dit about Herc tipping was really interesting. I nearly had an accidental tip at Brüggen. The aircraft was heavy, but trimmed for all aspects of operation required. However, with the stool out and with the aircraft sitting on a sloping pan, downwards nose to tail, combined with the wind conditions and no crew onboard, the nose wheel was teetering. Although eager to have the aircraft closed up, ready for the crew to depart immediately on their return from the duty free run, I decided I didn’t fancy being the subject of a unit inquiry, so the ramp was lowered and the elephant's foot put back in place. All was well.

My other Herc tipping story comes about from a trip out of the A400M assembly line, when I was working for a civvy company. We were given a tour of the A400M cargo loading simulator by 2 Dutch ex-ALMs. Noting how high the load bed is off the floor and thinking of loading long single piece loads and not realising at that point that the aircraft can kneel, I asked if the aircraft could be tipped, like a Herc! The 2 ALMs looked shocked and stated in no uncertain terms that a Herc cannot be tipped. My response being ‘that may be the case in the Dutch Air Force…’

Steve Harpum’s dit chimed with me too! I think I know the ‘scruffy’ officer to whom he refers! If it’s who I think it is, he left the RAF after a few years service, but returned some years later and had a healthy stint back in blue, although I think he was kept a long way away from ac! No name, no pack drill!

Anyway, keep them coming, I enjoyed the read and reminiscing.

Subject: Facebook Entry

Hello Tony,

Many thanks for the latest edition of the OBA newsletter. A fascinating read.

Ron Turley’s dit about Herc tipping was really interesting. I nearly had an accidental tip at Brüggen. The aircraft was heavy, but trimmed for all aspects of operation required. However, with the stool out and with the aircraft sitting on a sloping pan, downwards nose to tail, combined with the wind conditions and no crew onboard, the nose wheel was teetering. Although eager to have the aircraft closed up, ready for the crew to depart immediately on their return from the duty free run, I decided I didn’t fancy being the subject of a unit inquiry, so the ramp was lowered and the elephant's foot put back in place. All was well.

My other Herc tipping story comes about from a trip out of the A400M assembly line, when I was working for a civvy company. We were given a tour of the A400M cargo loading simulator by 2 Dutch ex-ALMs. Noting how high the load bed is off the floor and thinking of loading long single piece loads and not realising at that point that the aircraft can kneel, I asked if the aircraft could be tipped, like a Herc! The 2 ALMs looked shocked and stated in no uncertain terms that a Herc cannot be tipped. My response being ‘that may be the case in the Dutch Air Force…’

Steve Harpum’s dit chimed with me too! I think I know the ‘scruffy’ officer to whom he refers! If it’s who I think it is, he left the RAF after a few years service, but returned some years later and had a healthy stint back in blue, although I think he was kept a long way away from ac! No name, no pack drill!

Anyway, keep them coming, I enjoyed the read and reminiscing.

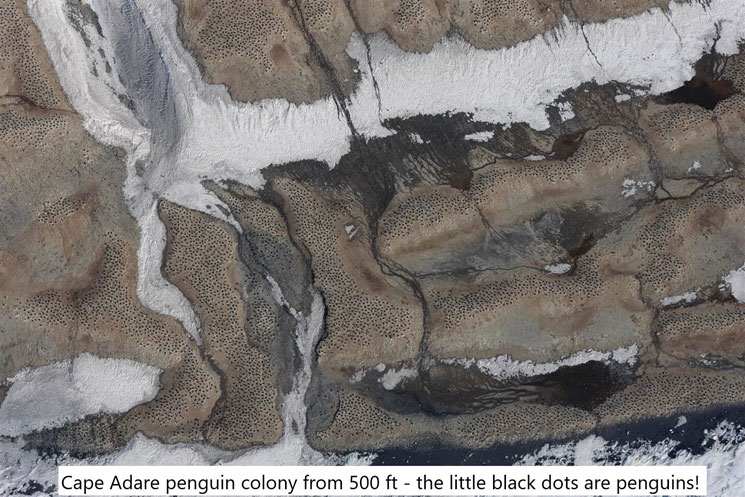

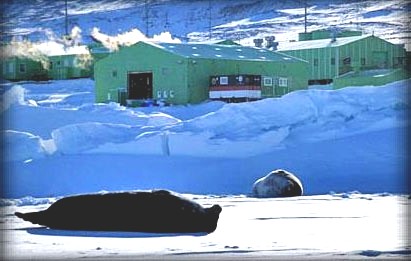

RAF in the Arctic Circle for Operation Boxtop

07 May 2025 - Twelve members of No. 99 Squadron RAF have spent the past week in the Arctic Circle to help resupply the most northerly station on Earth. The RAF C-17 Globemaster aircrew and ground support crew have been working alongside their Canadian counterparts as they resupply Canadian Forcers Station (CFS) Alert, more than 1,100 miles inside the Arctic Circle.

Flight Lieutenant Shaw, Junior co-pilot, said, “It’s been amazing to learn from the Canadians. These guys are born for this stuff and training this far North is an awesome opportunity we can’t get anywhere else.”

At more than 82 degrees North, CFS Alert is the most northerly permanent settlement on Earth that conducts critical climate change research as well as a number of Canadian Forces operations, but when the Arctic Sea freezes over every year, the only way in or out is by C-17 or C-130 aircraft landing on a 5,500 foot long snow and gravel runway.

Known as Operation Boxtop, the resupply happens twice a year when a C-17 from 429 (T) Squadron RCAF shuttles between Pituffik Space Base in Greenland and CFS Alert, delivering fuel and equipment in order to keep it running throughout the brutal Arctic winters, and now, for the second year running, the RAF crews joined them to study how their allies from the Great White North conduct polar operations and to learn their techniques for landing on semi-prepared ice runways.

Over the total two week duration of Operation Boxtop, the crews delivered nearly two million litres of jet fuel straight from the aircraft’s tanks to containers in Alert that will run everything from heaters and generators to radios and scientific equipment.

Flight Lieutenant Chandler, RAF detachment commander, said, “Flying in the extreme north presents a number of challenges that us Brits aren’t used to. When it’s -40°C even the simplest things can get difficult real quick, and when you’re landing a 200-ton jet on a strip less than half the length of Heathrow, that’s also covered in ice, it’s far from simple!”

raf.mod.uk

Flight Lieutenant Shaw, Junior co-pilot, said, “It’s been amazing to learn from the Canadians. These guys are born for this stuff and training this far North is an awesome opportunity we can’t get anywhere else.”

At more than 82 degrees North, CFS Alert is the most northerly permanent settlement on Earth that conducts critical climate change research as well as a number of Canadian Forces operations, but when the Arctic Sea freezes over every year, the only way in or out is by C-17 or C-130 aircraft landing on a 5,500 foot long snow and gravel runway.

Known as Operation Boxtop, the resupply happens twice a year when a C-17 from 429 (T) Squadron RCAF shuttles between Pituffik Space Base in Greenland and CFS Alert, delivering fuel and equipment in order to keep it running throughout the brutal Arctic winters, and now, for the second year running, the RAF crews joined them to study how their allies from the Great White North conduct polar operations and to learn their techniques for landing on semi-prepared ice runways.

Over the total two week duration of Operation Boxtop, the crews delivered nearly two million litres of jet fuel straight from the aircraft’s tanks to containers in Alert that will run everything from heaters and generators to radios and scientific equipment.

Flight Lieutenant Chandler, RAF detachment commander, said, “Flying in the extreme north presents a number of challenges that us Brits aren’t used to. When it’s -40°C even the simplest things can get difficult real quick, and when you’re landing a 200-ton jet on a strip less than half the length of Heathrow, that’s also covered in ice, it’s far from simple!”

raf.mod.uk

From: Fred Hebb, Gold River, NS

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

When I was stationed at CFEHQ in Lahr, I had on occasion gone on exercises with the Army. On one occasion my Captain and I had to go to Bardufoss, Norway, on an exercise to redeploy the troops and equipment back to Canada by air and sea. The Captain asked me to get our gear organized, make transportation arrangements and such for our trip. Being an old Air Force guy I got the combat gear organized, got Base Traffic to book a flight to Oslo by SAS, hotel in Oslo and a flight to Bardufoss. I then called the Embassy in Oslo for a hotel in the town near the jetty from which the troops and equipment were departing. Sure enough there was a hotel near the jetty and we were booked. I told the Captain all arrangements were made and asked where our sleeping bags were. I said we didn’t need them as we were booked in a hotel, I thought he was going to faint as it was too late to make changes.

When we got to Norway it was cold and when we were invited to an “O” group, the Army Colonel told the Captain he had tents arranged for us, separate, I may add. The Captain told the Colonel we didn’t need them as we were staying in an hotel. I thought he was going to freak but didn’t, but he did, however, have a one-on-one conversation with the Captain. After he got over it the Captain told him that we needed a jeep to take us were we had to go; they gave us a Mercedes. We didn’t need the tents and other gear to survive the cold and had a pretty good time on my exercise in a nice warm hotel.

Happy days!

Fred

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

When I was stationed at CFEHQ in Lahr, I had on occasion gone on exercises with the Army. On one occasion my Captain and I had to go to Bardufoss, Norway, on an exercise to redeploy the troops and equipment back to Canada by air and sea. The Captain asked me to get our gear organized, make transportation arrangements and such for our trip. Being an old Air Force guy I got the combat gear organized, got Base Traffic to book a flight to Oslo by SAS, hotel in Oslo and a flight to Bardufoss. I then called the Embassy in Oslo for a hotel in the town near the jetty from which the troops and equipment were departing. Sure enough there was a hotel near the jetty and we were booked. I told the Captain all arrangements were made and asked where our sleeping bags were. I said we didn’t need them as we were booked in a hotel, I thought he was going to faint as it was too late to make changes.

When we got to Norway it was cold and when we were invited to an “O” group, the Army Colonel told the Captain he had tents arranged for us, separate, I may add. The Captain told the Colonel we didn’t need them as we were staying in an hotel. I thought he was going to freak but didn’t, but he did, however, have a one-on-one conversation with the Captain. After he got over it the Captain told him that we needed a jeep to take us were we had to go; they gave us a Mercedes. We didn’t need the tents and other gear to survive the cold and had a pretty good time on my exercise in a nice warm hotel.

Happy days!

Fred

From: Dougie Russell, Carlisle, Cumbria

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

Afraid memories are missing names, but have some details of my deployment to Bardufoss while serving as JNCO i/c UKMAMS Stores, Oct '89 - Jan '91.

I was tasked as a member of a team deployed by road to RAF Coltishall for 41 Squadron recovery from Bardufoss. There was a pre-warning that 3 of us were going to fly up to reinforce the team in Bardufoss as IALCE was in progress simultaneously. I had sent 5 dunnage kits up and requested they be stored in 41 underground HAS.

When I arrived, I found the kits next to the portacabin covered in snow and ice. I eventually got them moved and proceeded to load the C130 's using them. I lost count of how many aircraft we handled and how many days we were there. After lunch each day, we handled a B707 aircraft for IALCE which meant we were working 15-hour shifts. I seem to recall knocking Keith Parker over in the front hold of the B707 when we were stacking weapons bundles. I wish I could remember who else was on the team back then.

Regards,

Dougie

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

Afraid memories are missing names, but have some details of my deployment to Bardufoss while serving as JNCO i/c UKMAMS Stores, Oct '89 - Jan '91.

I was tasked as a member of a team deployed by road to RAF Coltishall for 41 Squadron recovery from Bardufoss. There was a pre-warning that 3 of us were going to fly up to reinforce the team in Bardufoss as IALCE was in progress simultaneously. I had sent 5 dunnage kits up and requested they be stored in 41 underground HAS.

When I arrived, I found the kits next to the portacabin covered in snow and ice. I eventually got them moved and proceeded to load the C130 's using them. I lost count of how many aircraft we handled and how many days we were there. After lunch each day, we handled a B707 aircraft for IALCE which meant we were working 15-hour shifts. I seem to recall knocking Keith Parker over in the front hold of the B707 when we were stacking weapons bundles. I wish I could remember who else was on the team back then.

Regards,

Dougie

Last Flight out of Vietnam

The cargo compartment of a 37SQN C-130A full of South Vietnamese refugees fleeing from the North Vietnamese army

A RAAF pilot and airfield defence guard recall the frantic departure at the end of the Vietnam war.

Only three RAAF aircraft were in Vietnam on Anzac Day in 1975, just days before the fall of Saigon. A Hercules flown by Flight Lieutenant Sam (Dave) Nicholls and Flight Lieutenant Brent Espeland had left Tan Son Nhut earlier, leaving only the backup aircraft, piloted then by Flying Officer Jack Fanderlinden, to pick up the stragglers; embassy staff who had missed the earlier flights, Vietnamese war orphans and their nurses, South Vietnamese allies, nuns from a nearby order and four Airfield Defence Guards (ADG), armed only with pistols as the Viet Cong approached.

ADG corporal (retd) Ian "Spike" Dainer, one of the four, recalls there were also a number of nuns with hairy legs, one even had a moustache among the crowds trying to board that last plane. "My job on the day was working out who was entitled to get on, to search luggage to make sure the flight was safe" he said, "We had a group captain trying to hurry us along paying lip service to security but he changed his tune when we found grenades in one of the bags.

"We were trying to get as many people aboard as we could, and things became contentious because the embassy staff were taking a lot of personal possessions; there were cartons of whiskey, Persian carpets and porcelain elephants taking up seats. It was at that point that the captain of the aircraft told me that we needed to take some of that stuff off so that we could get more people on board."

The last flight's pilot, Air Commodore (retd) and General Manager of RAAF Base Williamtown's Fighterworld, Jack Fanderlinden, held a reunion on April 30 at Fighterworld for his crew and their families to mark the 50th anniversary of the event. In a presentation prior to afternoon tea, Mr Fanderlinden recalled the missions leading up to the evacuation of Saigon.

Both men remembered the incongruity of the South Vietnamese civilians going about their daily chores as rocket and gunfire got even closer to the airfield where the Herc was loading. "There were people painting 'Tan Son Nhut' on the airfield tower. And they kept on painting, even as we were taking off," Mr Dainer said.

Mr Fanderlinden added, "I shared lunch with some Vietnamese workers who were just glad that the war would be over."

After citing statistics of Australians killed and wounded in a conflict with nearly 30% of the 35,000 veterans alive today suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, Mr Fandelinden outlined the fates of some of the rescued war orphans who overcame adversities to lead successful lives in Australia. "It is important to remember the human costs of war," he said.

airforcenewspaper.defence.gov.au/FLTLT Julia Ravell

Only three RAAF aircraft were in Vietnam on Anzac Day in 1975, just days before the fall of Saigon. A Hercules flown by Flight Lieutenant Sam (Dave) Nicholls and Flight Lieutenant Brent Espeland had left Tan Son Nhut earlier, leaving only the backup aircraft, piloted then by Flying Officer Jack Fanderlinden, to pick up the stragglers; embassy staff who had missed the earlier flights, Vietnamese war orphans and their nurses, South Vietnamese allies, nuns from a nearby order and four Airfield Defence Guards (ADG), armed only with pistols as the Viet Cong approached.

ADG corporal (retd) Ian "Spike" Dainer, one of the four, recalls there were also a number of nuns with hairy legs, one even had a moustache among the crowds trying to board that last plane. "My job on the day was working out who was entitled to get on, to search luggage to make sure the flight was safe" he said, "We had a group captain trying to hurry us along paying lip service to security but he changed his tune when we found grenades in one of the bags.

"We were trying to get as many people aboard as we could, and things became contentious because the embassy staff were taking a lot of personal possessions; there were cartons of whiskey, Persian carpets and porcelain elephants taking up seats. It was at that point that the captain of the aircraft told me that we needed to take some of that stuff off so that we could get more people on board."

The last flight's pilot, Air Commodore (retd) and General Manager of RAAF Base Williamtown's Fighterworld, Jack Fanderlinden, held a reunion on April 30 at Fighterworld for his crew and their families to mark the 50th anniversary of the event. In a presentation prior to afternoon tea, Mr Fanderlinden recalled the missions leading up to the evacuation of Saigon.

Both men remembered the incongruity of the South Vietnamese civilians going about their daily chores as rocket and gunfire got even closer to the airfield where the Herc was loading. "There were people painting 'Tan Son Nhut' on the airfield tower. And they kept on painting, even as we were taking off," Mr Dainer said.

Mr Fanderlinden added, "I shared lunch with some Vietnamese workers who were just glad that the war would be over."

After citing statistics of Australians killed and wounded in a conflict with nearly 30% of the 35,000 veterans alive today suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, Mr Fandelinden outlined the fates of some of the rescued war orphans who overcame adversities to lead successful lives in Australia. "It is important to remember the human costs of war," he said.

airforcenewspaper.defence.gov.au/FLTLT Julia Ravell

Tony Street, Fort Erie, ON

Subject: Working in the Cold - Arctic Sleeping Bags.

Hello again Tony,

Many years ago, I was a Loadmaster on a ski-equipped C47 Dakota, flying well north of the Arctic Circle. We were tasked with going to Lake Hazen and opening up the science facility that had survived winter.

Subject: Working in the Cold - Arctic Sleeping Bags.

Hello again Tony,

Many years ago, I was a Loadmaster on a ski-equipped C47 Dakota, flying well north of the Arctic Circle. We were tasked with going to Lake Hazen and opening up the science facility that had survived winter.

Lake Hazen is located in the High Arctic

On taxiing up to the facility, we saw several tall masts bearing different colors. We were given a chart that told us what each color identified was buried there. The first effort was to shovel our way into the tent that was our residence. We had six people on the crew and we all dug in. After a long day it was time to sleep. Our tent had an oil burning stove that protected us from the -40º environment (we could work in shirt sleeves if we didn't break into a sweat).

The drill was to sleep naked in our sleeping bags as they were designed for this purpose. In the morning, I stuck my nose out and it told me that the heater was out. As l laid quietly, I could hear the rest of the crew surfacing, rolling around in their bags farting and mumbling. We were wating for someone to debag and light the heater. As I was the lowest rank in the crew, I silently awaited the inevitable, it came. The CO roared, "Street, get up and light the (*expletive*) stove!"

Our work here was done, it was time to head to Resolute Bay have a night's sleep and then head for home.

Best regards

Tony

The drill was to sleep naked in our sleeping bags as they were designed for this purpose. In the morning, I stuck my nose out and it told me that the heater was out. As l laid quietly, I could hear the rest of the crew surfacing, rolling around in their bags farting and mumbling. We were wating for someone to debag and light the heater. As I was the lowest rank in the crew, I silently awaited the inevitable, it came. The CO roared, "Street, get up and light the (*expletive*) stove!"

Our work here was done, it was time to head to Resolute Bay have a night's sleep and then head for home.

Best regards

Tony

From: Steve Harpum, Faringdon, Oxon

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

I recall getting off a C130 in some cold northern part of Norway in the early 80's during the annual 3 months' Royal Marines' training period, to be met by Hughie Curran, who was the embedded movements SNCO at that particular location.

Hughie was dressed in the latest winter warfare clothing which clearly hadn't been issued by MAMS Stores. When I asked what he was wearing, he replied that it was "Mafeking Kit".

I couldn't figure out what winter clothing might have been required at the Boer War siege of Mafeking and said something intelligent, like, "What?"

Hughie winked, and with a grin replied, "It's ma f*cking kit - youse can all get your own!"

Cheers, Steve

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

I recall getting off a C130 in some cold northern part of Norway in the early 80's during the annual 3 months' Royal Marines' training period, to be met by Hughie Curran, who was the embedded movements SNCO at that particular location.

Hughie was dressed in the latest winter warfare clothing which clearly hadn't been issued by MAMS Stores. When I asked what he was wearing, he replied that it was "Mafeking Kit".

I couldn't figure out what winter clothing might have been required at the Boer War siege of Mafeking and said something intelligent, like, "What?"

Hughie winked, and with a grin replied, "It's ma f*cking kit - youse can all get your own!"

Cheers, Steve

From: Jacques Guay, Port Charlotte, FL

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hello Tony:

I have a little story as far as working in the cold. Time was in 1974 at Thule Air Base in Greenland. We were doing the winter resupply of some food stuffs but, it was mainly diesel fuel and heating oil.

We were filling up fuel bladders on C130s. The weather was at least -30º to -40º (C or F, It did not matter.); cold enough to freeze unprotected skin. It was so cold, never felt anything like it. I must say that I was used to the cold but nothing like this, especially when the winter clothing got soaked with fuel. We did this for at least 2 weeks. My uniforms reeked of diesel. Even after washing, the smell remained.

Summer at Thule was more enjoyable due to the constant daylight and at -10º or so.

Jacques

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hello Tony:

I have a little story as far as working in the cold. Time was in 1974 at Thule Air Base in Greenland. We were doing the winter resupply of some food stuffs but, it was mainly diesel fuel and heating oil.

We were filling up fuel bladders on C130s. The weather was at least -30º to -40º (C or F, It did not matter.); cold enough to freeze unprotected skin. It was so cold, never felt anything like it. I must say that I was used to the cold but nothing like this, especially when the winter clothing got soaked with fuel. We did this for at least 2 weeks. My uniforms reeked of diesel. Even after washing, the smell remained.

Summer at Thule was more enjoyable due to the constant daylight and at -10º or so.

Jacques

New Zealand Welcomes Spanish-Built VAMTAC ST5

The New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) has taken a significant step toward modernizing its tactical mobility and digital warfare capabilities with the arrival of its first Spanish-made VAMTAC ST5 prototype vehicle.

Delivered from the UROVESA military vehicle manufacturing facility in Galicia, Spain, the prototype was transported aboard one of the Royal New Zealand Air Force’s newly acquired C-130J-30 Hercules aircraft. This delivery marks the beginning of a transformative program aimed at replacing the NZDF’s most frequently deployed operational vehicle fleet, with a particular emphasis on advanced communications integration.

armyrecognition.com

Delivered from the UROVESA military vehicle manufacturing facility in Galicia, Spain, the prototype was transported aboard one of the Royal New Zealand Air Force’s newly acquired C-130J-30 Hercules aircraft. This delivery marks the beginning of a transformative program aimed at replacing the NZDF’s most frequently deployed operational vehicle fleet, with a particular emphasis on advanced communications integration.

armyrecognition.com

From: Ian Berry, Eastleaze, Swindon, Wilts

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

I did a few cold weather jobs over the years and some were memorable.

In December 1972, I completed a Lone Ranger recovery which entailed a double shuttle between Wyton and Oerland in Norway. Three of the team stayed at Wyton and three in Norway. We were operating from a remote spot and the weather was atrocious. No shelter and we were not issued parkas. The wait for the C130 to return was agony and probably the nearest I got to getting hypothermia.

Just a month later in January 1973, in a scratch team which included Tony Willis, Bob Tring, Terry Fryer and Reg Carey, we completed a Belfast task taking helicopters from Boscombe Down to Ottawa and then on to Montreal for the night. It was -21ºC outside and this time we did have parkas. Dressed like Eskimos, the whole crew descended on the Old Munich Beer Keller which was huge inside and proceeded to have a fantastic night. I recall that more than one person was waiting for a taxi with the parka over their arm; such was the effect of schnapps!

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

I did a few cold weather jobs over the years and some were memorable.

In December 1972, I completed a Lone Ranger recovery which entailed a double shuttle between Wyton and Oerland in Norway. Three of the team stayed at Wyton and three in Norway. We were operating from a remote spot and the weather was atrocious. No shelter and we were not issued parkas. The wait for the C130 to return was agony and probably the nearest I got to getting hypothermia.

Just a month later in January 1973, in a scratch team which included Tony Willis, Bob Tring, Terry Fryer and Reg Carey, we completed a Belfast task taking helicopters from Boscombe Down to Ottawa and then on to Montreal for the night. It was -21ºC outside and this time we did have parkas. Dressed like Eskimos, the whole crew descended on the Old Munich Beer Keller which was huge inside and proceeded to have a fantastic night. I recall that more than one person was waiting for a taxi with the parka over their arm; such was the effect of schnapps!

RAF Parka Circa 1980

RAF Mukluks Circa 1980

The Old Munich Beer Keller in Montreal (no longer there)

EXERCISE HARDFALL '81 This article was originally written for a civilian aviation enthusiasts' newsletter...

Every winter during the Cold War (no pun intended), the Army and Royal Marines would send elements to Norway to train in winter warfare. The Marines would participate in Exercises Clockwork and Pendulum in Northern Norway. The Army Battalion and supporting elements of AMF(L) – ACE (Allied Command Europe) Mobility Force (Land) would exercise in South Western Norway, inland from Bergen. This was Exercise Hardfall '81.

In late November 1980, whilst serving as a Flt Sgt on a Mobile Team of UKMAMS at RAF Lyneham, I was advised that I had ‘lost’ the raffle! I had been selected to become the Air Liaison Officer (ALO) attached to 50 Movement Control (MC) Squadron Royal Corps of Transport (RCT). When not deployed on tasks they were based close by at South Cerney (formerly RAF South Cerney). Until 33 Squadron arrived in-theatre with their Puma helicopters, I would be the only RAF rep amongst 2,000 soldiers.

In December 1980 I attended a couple of comprehensive briefings at South Cerney. My Arctic/Winter clothing would all be issued by my own Squadron Stores at Lyneham. This was with the exception of a pair of snow gaiters which came in very handy. They look like footless socks made of Gore-Tex and are pulled up over your lower legs and tied off below the knee. The lower part covers your boots and laces and clips together under the sole. This prevents any snow getting into your boots and helps keep your feet snug and dry.

Every winter during the Cold War (no pun intended), the Army and Royal Marines would send elements to Norway to train in winter warfare. The Marines would participate in Exercises Clockwork and Pendulum in Northern Norway. The Army Battalion and supporting elements of AMF(L) – ACE (Allied Command Europe) Mobility Force (Land) would exercise in South Western Norway, inland from Bergen. This was Exercise Hardfall '81.

In late November 1980, whilst serving as a Flt Sgt on a Mobile Team of UKMAMS at RAF Lyneham, I was advised that I had ‘lost’ the raffle! I had been selected to become the Air Liaison Officer (ALO) attached to 50 Movement Control (MC) Squadron Royal Corps of Transport (RCT). When not deployed on tasks they were based close by at South Cerney (formerly RAF South Cerney). Until 33 Squadron arrived in-theatre with their Puma helicopters, I would be the only RAF rep amongst 2,000 soldiers.

In December 1980 I attended a couple of comprehensive briefings at South Cerney. My Arctic/Winter clothing would all be issued by my own Squadron Stores at Lyneham. This was with the exception of a pair of snow gaiters which came in very handy. They look like footless socks made of Gore-Tex and are pulled up over your lower legs and tied off below the knee. The lower part covers your boots and laces and clips together under the sole. This prevents any snow getting into your boots and helps keep your feet snug and dry.

Hardfall '81 Area - Bergen/Voss/Ulvik

South Cerney - Home of 50MC Sqn RCT - 29 Regt.

The Officer Commanding of 50MC Sqn was Major Ritson Harrison and we hit it off quite well. On his unit there was also an Army WO1 who was the Senior Movements Controller (SMC) and a WO2 who was the Sqn Sgt Major (SSM) and was responsible for discipline. They were both great guys and that really helped seeing as we would be spending many weeks together. We would all deploy to Bomoen Norwegian Army Camp, near Voss, in early January ’81 as part of the advance party. We would fly into Bergen /Flesland utilising 2 x C130 Hercules for this task. We would then have 7-10 days to prepare the camp and other areas before the main party arrived. This was planned utilising 2 x LSLs (Landing Ship Logistics), Sir Geraint and Sir Tristram, both sailing from the Army Port of Marchwood in Southampton. Recovery of all the troops would be by air at the end of March.

Even though I was to be the only RAF Rep attached to AMF (L), there was a ‘Brother in Arms’ carrying out a similar function with the Royal Marines in Trondheim. A good pal of mine, Tony, a Sgt from another team. When not working with the Marines/Army in the HQ he would also cover all aircraft movements at the airfield at Værnes.

That year Christmas flew by and very quickly January arrived. I met up with the Advance Party at Lyneham and we deployed to Bergen on board C130 XV204 with 3 x Landrovers and trailers and then drove through some beautiful scenery to Voss. All the UK vehicles had studded tyres, which I discovered were not that clever and it was also the first time I encountered snow chains. Once outside of Bergen, all the roads had a surface consisting of at least a foot of ice. Throughout the whole deployment I decided to leave the driving to the professionals. As it was, I was to witness several bumps and scrapes before the exercise ended.

Even though I was to be the only RAF Rep attached to AMF (L), there was a ‘Brother in Arms’ carrying out a similar function with the Royal Marines in Trondheim. A good pal of mine, Tony, a Sgt from another team. When not working with the Marines/Army in the HQ he would also cover all aircraft movements at the airfield at Værnes.

That year Christmas flew by and very quickly January arrived. I met up with the Advance Party at Lyneham and we deployed to Bergen on board C130 XV204 with 3 x Landrovers and trailers and then drove through some beautiful scenery to Voss. All the UK vehicles had studded tyres, which I discovered were not that clever and it was also the first time I encountered snow chains. Once outside of Bergen, all the roads had a surface consisting of at least a foot of ice. Throughout the whole deployment I decided to leave the driving to the professionals. As it was, I was to witness several bumps and scrapes before the exercise ended.

Bomoen Camp - BV202 Snocats to the right

The scary road down to the fjord town of Ulnik

Once we arrived at Bomoen and got sorted out there was quite a list of ‘to dos’. The Camp in its entirety had been handed over to the UK detachment. From the following week I was going to handle a staging C130 from Lyneham every Tuesday and Friday at Flesland Airport/Airfield. The aircraft would then fly on to Trondheim and then back to UK. Throughout the exercise the aircraft all flew this route and my suggestion that the route be alternated every other flight fell on ‘deaf’ ears! Every time there was a flight I would travel down to Bergen by train from Voss the night before. I would then be met by one of the RCT Detachment who were to assist at the airfield and were living at Sverresborg Barracks with the Norwegian Army. I would always stay there overnight and after handling the aircraft would reverse the route the next day. By the end of the detachment I had travelled a lot of train miles. The train journey itself was quite pleasant and stops on the way included a junction joining the famous Flam railway and town called Dale. This was famous for making the traditional thick woollen Norwegian cardigans, still available for about £200 each. Voss is also alongside a huge lake which was frozen solid. Towering over the place is a mountain known as The Hangar, 2,700ft in height, and a famous ski area.

Along with the Advance Party at Bomoen was a member of the Expeditionary Forces Institute (EFI). These men and women are all employees of NAAFI but when on exercise or operations they ‘don’ a uniform as part of the TA and become known as EFI. Already positioned at Bomoen was a shipping container full of ‘goodies’, aka Duty Free alcohol. In 1981, a litre bottle of Teachers Whisky was £6 in the shops and £3 duty free. For my ‘recce’ in Bergen I bought a case of a dozen bottles. My first task was to get to Flesland Airport and make some contacts. There are two parts to this airport, one civilian and one military. No aircraft of the Royal Norwegian Air Force are permanently based at Flesland but they handle many visitors and squadron detachments. Unseen from the civil side, there is a ‘Rock Hangar’ where most of the equipment and personnel are housed. This hangar has literally been hewn out of the granite rock. Being in uniform, this opens many doors and I was made most welcome. I was introduced to a RNoAF Major who was in charge of the ground equipment and aircraft handlers. I explained my task and that there would be visiting RAF aircraft at least twice every week. I would have an army working party but anticipated that sometimes I would need the assistance of large forklifts as well as marshalling and handling. He advised me that he had his own priorities and he would try and help when he could. I then produced three bottles of whisky which I said were for him and his team, this prompted the reply that I would get immediate assistance any time I wanted it! (At this time a bottle of spirits in Norway retailed at £60 a bottle).

Along with the Advance Party at Bomoen was a member of the Expeditionary Forces Institute (EFI). These men and women are all employees of NAAFI but when on exercise or operations they ‘don’ a uniform as part of the TA and become known as EFI. Already positioned at Bomoen was a shipping container full of ‘goodies’, aka Duty Free alcohol. In 1981, a litre bottle of Teachers Whisky was £6 in the shops and £3 duty free. For my ‘recce’ in Bergen I bought a case of a dozen bottles. My first task was to get to Flesland Airport and make some contacts. There are two parts to this airport, one civilian and one military. No aircraft of the Royal Norwegian Air Force are permanently based at Flesland but they handle many visitors and squadron detachments. Unseen from the civil side, there is a ‘Rock Hangar’ where most of the equipment and personnel are housed. This hangar has literally been hewn out of the granite rock. Being in uniform, this opens many doors and I was made most welcome. I was introduced to a RNoAF Major who was in charge of the ground equipment and aircraft handlers. I explained my task and that there would be visiting RAF aircraft at least twice every week. I would have an army working party but anticipated that sometimes I would need the assistance of large forklifts as well as marshalling and handling. He advised me that he had his own priorities and he would try and help when he could. I then produced three bottles of whisky which I said were for him and his team, this prompted the reply that I would get immediate assistance any time I wanted it! (At this time a bottle of spirits in Norway retailed at £60 a bottle).

The Rock Hangar - RNoAF Station Flesland

Bergen Flesland Airport - RNoAF bottom/Civil Top

I then made my way to the civilian side of the airport and visited the offices of SAS (The Airline, NOT the hooligans!). I met the Apron Services Manager and once again explained my task and what equipment and assistance I sought. They would also look after the refuelling. Without any cajoling the Manager and SAS were very helpful, even so, I donated some more whisky. Whilst with Apron services they showed me around their facilities and equipment. I was told that as I was ‘au fair’ with the operation of everything from baggage loaders to motorised steps I had their permission to operate them whenever I needed to. As on many occasions, I received far better cooperation than at certain airfields in the UK. It was a very productive day and I had achieved a lot in my preparation to handle the aircraft soon to start visiting.

Back in Bomoen, we had been allocated some office space and I also met the Norwegian army major who was to be our liaison officer. Like most Norwegians, he spoke good English; in fact 9 out of 10 Norwegians speak English. When the main Party was due to arrive by sea, the plan was that the LSLs would discharge their cargoes at a small port called Ulvik, at the head of the Granvin Fjord. There it transpired, was a NATO funded concrete jetty. My next outing was in fact to Ulvik along with the OC 50MC Sqn and his driver. The drive down the winding roads was quite an experience. The jetty was inspected and close by we looked at a small ferry capable of carrying some 8 vehicles at a time. The reason being that from arrival, the soldiers and equipment would disperse in several directions. They would then carry out their own unit training and eventually all meet up for a big ‘war-game’ towards the end of the exercise. Having nothing better to do, I assisted the OC in taking measurements of the ferry deck to help with later planning. Once this was completed we had a civilised coffee sat on the snow swept veranda of a local hotel with an amazing backdrop of fjords and mountains.

Back in Bomoen, we had been allocated some office space and I also met the Norwegian army major who was to be our liaison officer. Like most Norwegians, he spoke good English; in fact 9 out of 10 Norwegians speak English. When the main Party was due to arrive by sea, the plan was that the LSLs would discharge their cargoes at a small port called Ulvik, at the head of the Granvin Fjord. There it transpired, was a NATO funded concrete jetty. My next outing was in fact to Ulvik along with the OC 50MC Sqn and his driver. The drive down the winding roads was quite an experience. The jetty was inspected and close by we looked at a small ferry capable of carrying some 8 vehicles at a time. The reason being that from arrival, the soldiers and equipment would disperse in several directions. They would then carry out their own unit training and eventually all meet up for a big ‘war-game’ towards the end of the exercise. Having nothing better to do, I assisted the OC in taking measurements of the ferry deck to help with later planning. Once this was completed we had a civilised coffee sat on the snow swept veranda of a local hotel with an amazing backdrop of fjords and mountains.

RFA LSL - Sir Tristrum

RFA LSL - Sir Geraint

Prior to the arrival of the Main Party, immaterial of rank, we all shared the facilities offered by the Officers' Mess which was located atop a 500ft snow covered hillock and surrounded by trees. Access to it was by following an icy chicane, treading very carefully. Without dwelling on the matter, I had an unfortunate accident when I attempted to descend from the top to the bottom using a winding path amongst the trees. On my second step I slipped and then shot down the hill in about six seconds, my head bouncing off several trees and rocks on the way down.

Being full of NAAFI Duty Free, I felt no pain at the time but when I got back to our chalet and stared into the mirror, desperately trying to focus, I knew something was not quite right. Then I saw it, some of my earlobe was ‘dangling’, and I also felt the warm trickle of blood. With no further ado, I then sought out the Doctor from the RAMC; the same chap I had been drinking with only recently. Six stitches later all was repaired.

In what seemed no time at all, the Main party were on their way aboard the LSLs. The infantry battalion on board consisted of members of 1PWO (Prince of Wales Own) who were a Yorkshire Battalion and their cap badge was that of the West Yorkshire Horse, cruelly likened to a rocking horse. Leaving just a skeleton staff back at Bomoen, we all travelled down to Ulvik to meet the ships. Unfortunately the arrival had been delayed by 24 hours; the reason being that a young soldier had fallen over the side from one of the LSLs and was missing, presumed dead. He had been ‘horsing around’ and was stood on the railing when he lost his balance. As UK Military Maritime Regulations dictated, a Unit Inquiry was held at sea. In typical black military humour we heard later that 1PWO now stood for ‘One person went overboard!’

Being full of NAAFI Duty Free, I felt no pain at the time but when I got back to our chalet and stared into the mirror, desperately trying to focus, I knew something was not quite right. Then I saw it, some of my earlobe was ‘dangling’, and I also felt the warm trickle of blood. With no further ado, I then sought out the Doctor from the RAMC; the same chap I had been drinking with only recently. Six stitches later all was repaired.

In what seemed no time at all, the Main party were on their way aboard the LSLs. The infantry battalion on board consisted of members of 1PWO (Prince of Wales Own) who were a Yorkshire Battalion and their cap badge was that of the West Yorkshire Horse, cruelly likened to a rocking horse. Leaving just a skeleton staff back at Bomoen, we all travelled down to Ulvik to meet the ships. Unfortunately the arrival had been delayed by 24 hours; the reason being that a young soldier had fallen over the side from one of the LSLs and was missing, presumed dead. He had been ‘horsing around’ and was stood on the railing when he lost his balance. As UK Military Maritime Regulations dictated, a Unit Inquiry was held at sea. In typical black military humour we heard later that 1PWO now stood for ‘One person went overboard!’

The actual arrival of the ships was quite impressive and one at a time they both reversed towards the small concrete pier and opened their rear loading ramps. Out poured all kinds of military hardware from 4 ton trucks, Landrovers, BV202 SnoCats to artillery pieces. Some were directed onto the ferry we had chartered earlier to cross the fjord and others started the climb back to Bomoen. All this activity had attracted a small crowd of locals who came to watch. I also found it amusing when two of the Chinese Crew of the LSL were being snowballed by the local children. Eventually all the equipment had been offloaded, the ships departed and Exercise Hardfall ’81 had begun.

Back at Bomoen, four Puma helicopters of 33 Squadron from RAF Odiham had also arrived, as well as a pair of Army Air Corps Gazelle helicopters.

Back at Bomoen, four Puma helicopters of 33 Squadron from RAF Odiham had also arrived, as well as a pair of Army Air Corps Gazelle helicopters.

BV202 Sno-Cat

33 Squadron RAF Pumas at Bomoen

The next day I travelled down to the Airport to handle my first C130 Hercules visitor, this was a ‘special’ and full of ammunition for the exercise. I called upon the RNoAF for assistance with a large forklift and they immediately assisted. For the next several weeks I handled a C130 every Tuesday and Friday and the odd special, normally an aeromed task as well.

One unusual load was the reception of 2 x BV202 SnoCats. These are tracked vehicles and ideal for travel over snow. To fly them on board a C130 we installed a FPK (Floor Protection Kit) basically consisting of plywood sheets with pre-cut holes in them to fit over the aircraft floor points. This served the purpose of protecting the aircraft floor from any damage from the tracks.

The assistance provided by the RNoAF and SAS was always outstanding. Back at Bomoen, in-between my airport duties; I handled all requests for the movement of passengers either to travel up to Trondheim or back to UK. I also accepted bids to move urgent freight back to UK as well.

One unusual load was the reception of 2 x BV202 SnoCats. These are tracked vehicles and ideal for travel over snow. To fly them on board a C130 we installed a FPK (Floor Protection Kit) basically consisting of plywood sheets with pre-cut holes in them to fit over the aircraft floor points. This served the purpose of protecting the aircraft floor from any damage from the tracks.

The assistance provided by the RNoAF and SAS was always outstanding. Back at Bomoen, in-between my airport duties; I handled all requests for the movement of passengers either to travel up to Trondheim or back to UK. I also accepted bids to move urgent freight back to UK as well.

The same trick the RCT provided to bring the freight to the airport was also utilised to return whatever had arrived from UK. On one occasion an AOG spare arrived for the Army Air Corps and the other Gazelle helicopter (XX375) was sent to collect the spare. I graciously accepted the offer of a lift back and a bonus was we actually landed on the top of the Hangar mountain on the way back in.

RAF C130 on a typical Norwegian airfield

Army Air Corps Gazelle operating into Bomoen

For the uninitiated, the AAC as well as the RAF did not use any aircraft heating during this exercise. The reason was simply because of all the snow trodden inside by pax and the risk of the thawing snow getting into the electrics. With everyone wearing arctic clothing it was not an issue. I also learnt it was safer to ‘jump’ to the ground from inside a landed Puma as to use the step in these icy conditions could prove hazardous.

I also noticed that the RAF Engineers were ‘trialling’ Dew Suits. These were one piece quilted overalls for working outside in the elements. However, they all looked like ‘Michelin Men’ and the Dew Suits were never adopted because they were too cumbersome.

In February I had my first quite urgent and serious aeromed when we had to get a badly burned soldier back to UK for treatment. From what I can gather he was operating a Milan Anti-Tank Missile system when the system froze and on firing swung about and he got caught in the hot exhaust.

Back to my task of moving pax within Norway, with the absence of UK assets I was able to ‘tap’ into the Norwegian Military FlyRouter system. Conscription still existed in Norway and the country was divided in two; District Kommando Nord & Sud. (DKN & DKS). Anyone who lived north of a certain line would serve their years service in the South and vice versa. This approach also helped with the mindset of the conscripts as they couldn’t get home if hostilities started. To help the servicemen get home on leave and other occasions the Norwegians operated a free flight service every day. These aircraft could be RNoAF C130s or SAS DC9s. As part of NATO we were allowed access to this service.

I also noticed that the RAF Engineers were ‘trialling’ Dew Suits. These were one piece quilted overalls for working outside in the elements. However, they all looked like ‘Michelin Men’ and the Dew Suits were never adopted because they were too cumbersome.

In February I had my first quite urgent and serious aeromed when we had to get a badly burned soldier back to UK for treatment. From what I can gather he was operating a Milan Anti-Tank Missile system when the system froze and on firing swung about and he got caught in the hot exhaust.

Back to my task of moving pax within Norway, with the absence of UK assets I was able to ‘tap’ into the Norwegian Military FlyRouter system. Conscription still existed in Norway and the country was divided in two; District Kommando Nord & Sud. (DKN & DKS). Anyone who lived north of a certain line would serve their years service in the South and vice versa. This approach also helped with the mindset of the conscripts as they couldn’t get home if hostilities started. To help the servicemen get home on leave and other occasions the Norwegians operated a free flight service every day. These aircraft could be RNoAF C130s or SAS DC9s. As part of NATO we were allowed access to this service.

Image of a Milan ATGW (Anti-tank guided weapon)

RNoAF C130 Hercules - FlyRouter

During my extended time with the Army, I found most of them professional, competent and easy to get on with. Unlike the RAF SNCOs, theirs seemed to shout a lot and any order was usually followed with an unnecessary threat! Some of the officers though, were different and I found this a source of entertainment. One gentleman I did not warm to was the Paymaster, a Captain in the RAPC. Whichever of the UK Armed Services you are in there will still be the same opportunity to claim what is legally entitled. When I submitted my expenses claim to the Paymaster for my trips to Bergen and elsewhere he would bluster and harrumph and go out of his way to block my claims. He was more annoyed I stood my ground whereas I suspect if I was in the Army I would have given up. I got my money which in turn paid for the whisky! The bottom line was I think he was being awkward to try and save on the paperwork, in essence, a lazy individual.

Some 7 weeks into the exercise I got permission from my OC to fly up to Trondheim for the weekend. My opposite number, Tony, working with the marines had told me there was to be a party. I flew up on the Friday C130 schedule (XV207) to Vaernes Airfield. From there, after helping ‘turn around’ the C130 we headed downtown in a Landrover, driven by one of the 50MC Sqn detachment. They took great delight in showing me the one and only roundabout in the area and demonstrated that which direction we used was optional! I then had a brief on the RCT set-up at Trondheim. The Army Lieutenant in charge was in fact to become my OC on JHSU in Germany some five years on. Tony was accommodated with the Royal Marines in the local barracks and they were great company. As promised, I attended a party ‘downtown’ on the Saturday night. Obviously the attraction of UK Duty Free alcohol was a magnet for many of the local girls!

On the Sunday evening I had to start my journey back to Bomoen. As I mentioned, the C130s only flew Bergen-Trondheim, my only way back was by train. As the MC Det also issued rail warrants they had booked me on an overnight sleeper Trondheim to Oslo. From there I would connect with another train and travel on to Bergen. This was my very first experience of a sleeper. I was allocated a compartment which had two bunk beds and shared the accommodation with a rather large Norwegian gentleman. I don’t remember most of the journey and arrived in Oslo around 7am on the Monday morning.

Some 7 weeks into the exercise I got permission from my OC to fly up to Trondheim for the weekend. My opposite number, Tony, working with the marines had told me there was to be a party. I flew up on the Friday C130 schedule (XV207) to Vaernes Airfield. From there, after helping ‘turn around’ the C130 we headed downtown in a Landrover, driven by one of the 50MC Sqn detachment. They took great delight in showing me the one and only roundabout in the area and demonstrated that which direction we used was optional! I then had a brief on the RCT set-up at Trondheim. The Army Lieutenant in charge was in fact to become my OC on JHSU in Germany some five years on. Tony was accommodated with the Royal Marines in the local barracks and they were great company. As promised, I attended a party ‘downtown’ on the Saturday night. Obviously the attraction of UK Duty Free alcohol was a magnet for many of the local girls!

On the Sunday evening I had to start my journey back to Bomoen. As I mentioned, the C130s only flew Bergen-Trondheim, my only way back was by train. As the MC Det also issued rail warrants they had booked me on an overnight sleeper Trondheim to Oslo. From there I would connect with another train and travel on to Bergen. This was my very first experience of a sleeper. I was allocated a compartment which had two bunk beds and shared the accommodation with a rather large Norwegian gentleman. I don’t remember most of the journey and arrived in Oslo around 7am on the Monday morning.

The fantastic Bergensbanen Railway

F16 Fighting Falcon of 388FW, Hill AFB, Utah

Some 90 minutes later I boarded the fantastic Bergensbanen scenic railway which goes from Oslo to Bergen. A journey of 308 miles and taking just under seven hours. In this time the train climbs to a height of 4,058ft and is the highest railway in Europe. The views on this journey were breathtaking and up on the plateau the snow is so deep you can sometimes only see the roof or chimneys of a house.

Even though the train passed through Voss on its way to Bergen I remained on board as I was back in the routine ready to meet the scheduled C130 the next morning. This train journey though was unforgettable and only recently I watched a documentary concerning this same journey narrated by Bill Neaghy.

In early March, RNoAF Flesland became quite busy when the Norwegians hosted a detachment of USAF F16 Falcons. They were part of the 388th Fighter Wing. These aircraft had staged all the way across from Hill Air Force Base in Utah; another great example of NATO cooperation and support for each other.

Even though the train passed through Voss on its way to Bergen I remained on board as I was back in the routine ready to meet the scheduled C130 the next morning. This train journey though was unforgettable and only recently I watched a documentary concerning this same journey narrated by Bill Neaghy.

In early March, RNoAF Flesland became quite busy when the Norwegians hosted a detachment of USAF F16 Falcons. They were part of the 388th Fighter Wing. These aircraft had staged all the way across from Hill Air Force Base in Utah; another great example of NATO cooperation and support for each other.

F16 at Bergen awaiting a B737 to clear the runway

It can get quite chilly!

By mid-March the exercise was drawing to a close. In some years a majority of the troops redeploy further north for a mass exercise, this year that did not happen. The two LSLs were to return to Ulvik and recover the equipment and some personnel back to UK by sea.

Most of 1PWO and supporting troops were to recover back to UK by air from Flesland. For this I was to handle some 7 x VC10 flights and a few C130s. To assist me, a MAMS team was deployed from my own squadron at Lyneham. All went without a hitch and within a week all that was left at Bomoen was the Rear Party; everything had gone full circle.

Along with the few remaining, I handled the last C130 (XV215) on the 30th March and flew back on the same aircraft. From a task I initially was not relishing, it in fact was quite enjoyable, bar the separation from my family. I also had one afternoon attempting to ski but in the end I had to agree with my pal Tony, who said ”Skiing was a blood sport!”

Most of 1PWO and supporting troops were to recover back to UK by air from Flesland. For this I was to handle some 7 x VC10 flights and a few C130s. To assist me, a MAMS team was deployed from my own squadron at Lyneham. All went without a hitch and within a week all that was left at Bomoen was the Rear Party; everything had gone full circle.

Along with the few remaining, I handled the last C130 (XV215) on the 30th March and flew back on the same aircraft. From a task I initially was not relishing, it in fact was quite enjoyable, bar the separation from my family. I also had one afternoon attempting to ski but in the end I had to agree with my pal Tony, who said ”Skiing was a blood sport!”

From: Mike Lefebvre, Oromocto, NB

Subject: Working in the Cold

Thank you for the topic, Tony .

As a Canadian, working in the cold is not unusual, even in the middle of summer we worked many times in areas above the Arctic Circle.

In my first 6 years as a MAMS member, I was in Thule for at least 5 Easter weekends. We were in Bardufoss staying in tents for one of those in the winter - the others in summer. I remember going to the mess for breakfast and they had every kind of fish imaginable, including caviar; went back for dinner and took a plate of food to my table, I poured some sauce on my rice and got a lot of laughs from the locals - what I thought was sauce was a light drink!

We were treated with a bus tour and saw salmon ladders in many areas. We drove through snow tunnels with the bus and saw locals on sleds, pulled by reindeer, clothed in fancy dress.

I was in Norway many times with MAMS in places like Bodo and Andoya, also Rotterdam, Netherlands and Copenhagen, Denmark. Then I became a Loadmaster on Hercules and went back to many just passing by. I went back flying into Bardufoss, 4 more times, the fourth was in daylight hours and I could not believe my eyes the mountains we were flying through - following valley after valley till finally seeing a runway in a small valley. It was like doing 4 approaches; in the dark it was fine, but in daylight, it was not. Alert, Northwest Territories became 4 times a month, 12 months a year, destinations always cold and unusual loads to deal with.

So often around the world, that I missed my sister’s wedding while in Norway.

Thanks for your newsletters and have a great summer in a warm place with good friends.

Mike

Subject: Working in the Cold

Thank you for the topic, Tony .

As a Canadian, working in the cold is not unusual, even in the middle of summer we worked many times in areas above the Arctic Circle.

In my first 6 years as a MAMS member, I was in Thule for at least 5 Easter weekends. We were in Bardufoss staying in tents for one of those in the winter - the others in summer. I remember going to the mess for breakfast and they had every kind of fish imaginable, including caviar; went back for dinner and took a plate of food to my table, I poured some sauce on my rice and got a lot of laughs from the locals - what I thought was sauce was a light drink!

We were treated with a bus tour and saw salmon ladders in many areas. We drove through snow tunnels with the bus and saw locals on sleds, pulled by reindeer, clothed in fancy dress.

I was in Norway many times with MAMS in places like Bodo and Andoya, also Rotterdam, Netherlands and Copenhagen, Denmark. Then I became a Loadmaster on Hercules and went back to many just passing by. I went back flying into Bardufoss, 4 more times, the fourth was in daylight hours and I could not believe my eyes the mountains we were flying through - following valley after valley till finally seeing a runway in a small valley. It was like doing 4 approaches; in the dark it was fine, but in daylight, it was not. Alert, Northwest Territories became 4 times a month, 12 months a year, destinations always cold and unusual loads to deal with.

So often around the world, that I missed my sister’s wedding while in Norway.

Thanks for your newsletters and have a great summer in a warm place with good friends.

Mike

From: Paul “Taff” Kelly, Lyneham, Wilts

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

Back in the nineties, while on MAMS, we were tasked to assist Scouse Leman and his boys on the pans in Anchorage, Alaska. We were working at night with the temperature of -25ºC building pallets for a TriStar outbound load.

All was going well and after 4 hours of freezing conditions, the loadie signalled for us to close the freight door and remove the FMC (similar to a ConDec). Unfortunately, the local driver had forgotten to place dunnage under the metal footplates to avoid them from freezing to the icy pans. After what seemed like an eternity we were able to assist the driver in releasing the said plates, allowing him to reverse away which then enabled the by now 'frozen' loadie, to wrap up the kite. Then we all departed, back to the hotel for a well earned bevvy.

What a job, but fond memories!

Taff Kelly

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

Back in the nineties, while on MAMS, we were tasked to assist Scouse Leman and his boys on the pans in Anchorage, Alaska. We were working at night with the temperature of -25ºC building pallets for a TriStar outbound load.

All was going well and after 4 hours of freezing conditions, the loadie signalled for us to close the freight door and remove the FMC (similar to a ConDec). Unfortunately, the local driver had forgotten to place dunnage under the metal footplates to avoid them from freezing to the icy pans. After what seemed like an eternity we were able to assist the driver in releasing the said plates, allowing him to reverse away which then enabled the by now 'frozen' loadie, to wrap up the kite. Then we all departed, back to the hotel for a well earned bevvy.

What a job, but fond memories!

Taff Kelly

From: Stephen Davey, Tadcaster, North Yorks

Subject: Working in the Cold

Tony,

I don't know if this counts, but imagine the North Yorks Moors, January 1978, Jet Provost T5A XW426 had crashed near Dalby forest (both crew members had ejected safely). A crash guard had to be mounted from Linton-on-Ouse to protect the crash site until the AAIB team from Farnborough arrived; yours truly was selected amongst others.

We arrived at Dalby mid-afternoon, set up a camp complete with tents about 200 yards from the crash site. By 4pm the temperature started to drop and by 6pm the temperature was -8º and the ground was frozen. It turned out to be one of the coldest nights of the year. We actually lit a fire to keep warm, which probably wasn't the best of ideas given that the smell of aviation fuel was in the air!

There was good news however, because the landlord of the "Fox and the Rabbit" (if you know the area you'll know the pub) visited us with a couple of crates of beer and also invited those not on guard duty to come to the pub for a hot meal. Can you imagine that happening now?.

The following morning we were relieved and taken back to Linton where a warm bed was waiting - happy memories?

Regards,

Steve

Subject: Working in the Cold

Tony,

I don't know if this counts, but imagine the North Yorks Moors, January 1978, Jet Provost T5A XW426 had crashed near Dalby forest (both crew members had ejected safely). A crash guard had to be mounted from Linton-on-Ouse to protect the crash site until the AAIB team from Farnborough arrived; yours truly was selected amongst others.

We arrived at Dalby mid-afternoon, set up a camp complete with tents about 200 yards from the crash site. By 4pm the temperature started to drop and by 6pm the temperature was -8º and the ground was frozen. It turned out to be one of the coldest nights of the year. We actually lit a fire to keep warm, which probably wasn't the best of ideas given that the smell of aviation fuel was in the air!

There was good news however, because the landlord of the "Fox and the Rabbit" (if you know the area you'll know the pub) visited us with a couple of crates of beer and also invited those not on guard duty to come to the pub for a hot meal. Can you imagine that happening now?.

The following morning we were relieved and taken back to Linton where a warm bed was waiting - happy memories?

Regards,

Steve

A new member joining us recently is:

Simon Hawkins, Chichester, West Sussex

Welcome to the OBA!

From: Budgie Baigent, Takaka, Tasman

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

Too many stories come to mind but here’s a couple:

In Dec 1982, while I was working at McMurdo Station Antarctica, Prince Edward happened to visit Scott Base and South Pole. He was 18 years old then and the first member of the royal family to visit Antarctica (at the time he was a house tutor and junior master at a private boys' school in Wanganui, NZ). In those days Husky dogs were used to pull the sleds for the Antarctica NZ scientists. As was tradition for VIP visitors to Scott Base, the Husky team was used to convey the visitor(s) from the aircraft and across the sea ice to Base. As the opportunity was there… I rode on the sled out to the aircraft. Unbeknown to me it was the first jaunt of the day for the huskies and they were literally busting their guts to get underway – I say literally because having been on the chain for several hours that was their first opportunity to relieve their pent-up wind! Never before nor since have I smelt such putrid farts as they raced off toward the ice runway. I guess that’s what you get from a diet of seal blubber but there was nowhere I could go – an experience I will never forget.

Subject: Working in the Cold

Hi Tony,

Too many stories come to mind but here’s a couple:

In Dec 1982, while I was working at McMurdo Station Antarctica, Prince Edward happened to visit Scott Base and South Pole. He was 18 years old then and the first member of the royal family to visit Antarctica (at the time he was a house tutor and junior master at a private boys' school in Wanganui, NZ). In those days Husky dogs were used to pull the sleds for the Antarctica NZ scientists. As was tradition for VIP visitors to Scott Base, the Husky team was used to convey the visitor(s) from the aircraft and across the sea ice to Base. As the opportunity was there… I rode on the sled out to the aircraft. Unbeknown to me it was the first jaunt of the day for the huskies and they were literally busting their guts to get underway – I say literally because having been on the chain for several hours that was their first opportunity to relieve their pent-up wind! Never before nor since have I smelt such putrid farts as they raced off toward the ice runway. I guess that’s what you get from a diet of seal blubber but there was nowhere I could go – an experience I will never forget.

Prince Edward on Husky Sled - Scott Base 1982

Later, circa 1990, I was the RNZAF Liaison Officer deployed to USN McMurdo Station to effect the turnaround of the Kiwi C130H’s during the annual resupply flights dubbed ‘Operation Ice Cube’. Due to crew duty regulations it was not possible to conduct same day turnarounds so the aircraft and crews overnighted at McMurdo and returned to Christchurch next day.

Back then the ‘airfield’ was actually sea ice, about 3 metres thick, and was operational for the period October until mid-December when the temperature rose and the ice started to melt. Our last Kiwi C130 departure that season went u/s [requiring a prop change?] so a second C130 with a new prop and maintenance team was sent from Christchurch to effect the repair. That aircraft also went u/s [can’t recall why] so a third aircraft was deployed to the ice. With 60% of the RNZAF’s C130 fleet stuck on the ice and the ice runway melting quickly it was a dire situation!

The ‘road’ from McMurdo to the ice runway was deteriorating rapidly with vehicles literally driving along ruts containing about 50cms of melted sea water meaning the ice thickness was reduced to 2.5 metres in places! The portable ‘Ice Tower’, Operations Centre, and several other portable huts had already been towed by bulldozer to ‘Williams Field’ as skied operations had already been transferred there.

The C130’s were eventually repaired, but by the time the last aircraft was ready to depart the crew had to be conveyed to the aircraft by helicopter as the ‘road’ was declared too dangerous and closed. The ice runway was so badly decayed that as that last Kiwi C130 got airborne, seals began to appear through cracks in the ice.

The ice runway was last used in the mid 2000’s and nowadays all wheeled aircraft utilize ‘Phoenix Airfield’, a permanent compacted snow runway. Further reading here; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice_Runway

Back then the ‘airfield’ was actually sea ice, about 3 metres thick, and was operational for the period October until mid-December when the temperature rose and the ice started to melt. Our last Kiwi C130 departure that season went u/s [requiring a prop change?] so a second C130 with a new prop and maintenance team was sent from Christchurch to effect the repair. That aircraft also went u/s [can’t recall why] so a third aircraft was deployed to the ice. With 60% of the RNZAF’s C130 fleet stuck on the ice and the ice runway melting quickly it was a dire situation!

The ‘road’ from McMurdo to the ice runway was deteriorating rapidly with vehicles literally driving along ruts containing about 50cms of melted sea water meaning the ice thickness was reduced to 2.5 metres in places! The portable ‘Ice Tower’, Operations Centre, and several other portable huts had already been towed by bulldozer to ‘Williams Field’ as skied operations had already been transferred there.

The C130’s were eventually repaired, but by the time the last aircraft was ready to depart the crew had to be conveyed to the aircraft by helicopter as the ‘road’ was declared too dangerous and closed. The ice runway was so badly decayed that as that last Kiwi C130 got airborne, seals began to appear through cracks in the ice.

The ice runway was last used in the mid 2000’s and nowadays all wheeled aircraft utilize ‘Phoenix Airfield’, a permanent compacted snow runway. Further reading here; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice_Runway

RNZAF C130's at the ice runway, McMurdo 1990 - Mt Erebus in the background

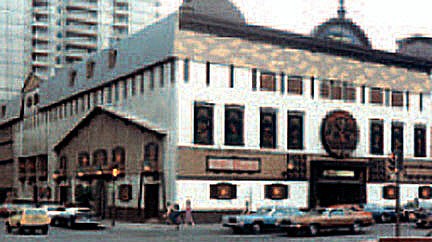

Counting Penguins: Penguin populations at several coastal colonies were counted using aerial reconnaissance, with high resolution photos taken from the C130 para door then analysed back at the research centre to determine an accurate count of breeding pairs and establish annual population trends.

Once the count was done there is nothing more exhilarating than flying low level, with the ramp down, over countless icebergs down McMurdo Sound and back to the ice runway. Another unforgettable experience

Once the count was done there is nothing more exhilarating than flying low level, with the ramp down, over countless icebergs down McMurdo Sound and back to the ice runway. Another unforgettable experience

Kindest regards,

Budgie

Budgie

From: Tomm Everett, Water Valley, AB

Subject: Working in the Cold - Frozen Adventure

Hello Tony,

I was on a MAMs team in 1970 and was deployed to Alaska on an exercise with the Canadian Airborne Regiment. Our team spent two weeks there unloading supplies to keep the troops going. The temperature ranged between -40º and -50º with winds gusting to 40 mph some days. The highway along the base had to be closed as the wind blowing across it formed icy conditions; it was actually blowing vehicles into the ditch. These conditions were very hard on personnel and equipment.

We were using a rough terrain forklift to unload pallets, the severe cold caused the hydraulic lines on the forklift to break, leaving us no way to offload. They directed us to an unused taxiway and we manually rolled pallets down the ramp and used a 3/4-ton truck to pull them out of the way using chains. When the regiment asked us where their supplies were, we directed them to the runway, after explaining the situation.