From: Charles Collier, Ewhurst, Surrey

Subject: Aden Days 1966

Aden from 1965 to 1967 was an eye-opener of a first tour of duty for a 24 year old RAF zombie officer doing my duty selling service scrap equipment to 70 odd Arab contractors.

Where I worked in Cemetery Valley, the Aden Forces Pistol Club had a range – so I joined them. The matches were grand affairs including when we visited Djibouti as guests of the French where lavish entertainment was laid on and no expense seemed to be spared. On the other hand, when the French were our guests in Aden, the celebrations were very muted under the stricture of non-public funds which were deemed sufficient by the Command Secretariat for the entertainment of foreign forces during matches. This situation prevailed throughout the two years I was on posting and was, to say the least, a complete embarrassment for us. Nobody complained - least of all the French - so we all had a good time while it lasted.

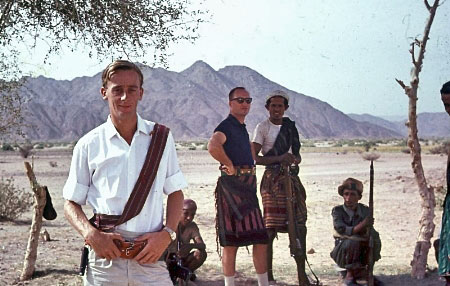

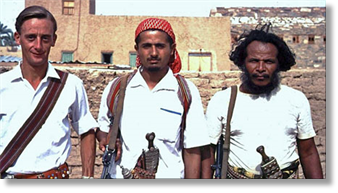

I was telephoned by a Sqn Ldr Alan D’Arcy, an Arabist of HQMEC, to ask as I was a member of the Aden Forces Pistol Club and had my own weapon would I be prepared to act as his personal escort as he was going to live with the Upper Aulaqi tribe of Arabs for some 10 days and I would be responsible for protecting his life – I was 25; so I agreed!

Subject: Aden Days 1966

Aden from 1965 to 1967 was an eye-opener of a first tour of duty for a 24 year old RAF zombie officer doing my duty selling service scrap equipment to 70 odd Arab contractors.

Where I worked in Cemetery Valley, the Aden Forces Pistol Club had a range – so I joined them. The matches were grand affairs including when we visited Djibouti as guests of the French where lavish entertainment was laid on and no expense seemed to be spared. On the other hand, when the French were our guests in Aden, the celebrations were very muted under the stricture of non-public funds which were deemed sufficient by the Command Secretariat for the entertainment of foreign forces during matches. This situation prevailed throughout the two years I was on posting and was, to say the least, a complete embarrassment for us. Nobody complained - least of all the French - so we all had a good time while it lasted.

I was telephoned by a Sqn Ldr Alan D’Arcy, an Arabist of HQMEC, to ask as I was a member of the Aden Forces Pistol Club and had my own weapon would I be prepared to act as his personal escort as he was going to live with the Upper Aulaqi tribe of Arabs for some 10 days and I would be responsible for protecting his life – I was 25; so I agreed!

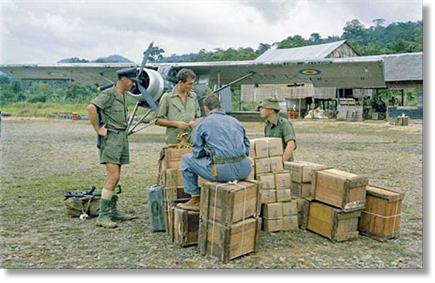

I took sufficient 9mm ammo boxes for the 10 days and waited for the call forward which had been agreed by my CO. We travelled out from Khormaksar on a Beverley of No 84 Sqn, staging at Habilayne camp and then onto Ataq where we were met by representatives of the Upper Aulaqi tribe including their leader called the Naib.

At this point I must explain the role of Alan D’Arcy’s trip up country. He was a secretarial officer at HQMEC but was also a fluent Arab speaker; and as such he had offered his services of Arabic translation to the HQ branch concerned. Hence, he was asked to visit the leader of the Upper Aulaqi tribe and to explain to him what British government policy was with regard to their tribal future in the politics of the day.

At this point I must explain the role of Alan D’Arcy’s trip up country. He was a secretarial officer at HQMEC but was also a fluent Arab speaker; and as such he had offered his services of Arabic translation to the HQ branch concerned. Hence, he was asked to visit the leader of the Upper Aulaqi tribe and to explain to him what British government policy was with regard to their tribal future in the politics of the day.

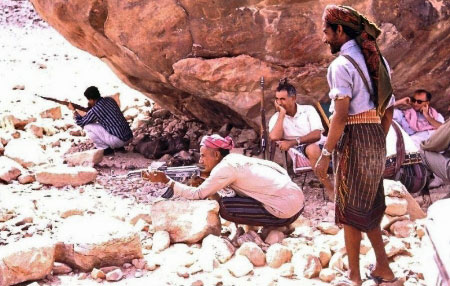

The Tribal leaders decided that the next day - after Alan and I were refreshed - we should all go for a picnic in the desert close to the edge of the Aulaqi territory.

The journey started early next morning before the sun rose too high in the sky so that we could get shelter from it, at the huge boulder you see here. Our day out was to include a sumptuous meal which would be slaughtered and cooked on site. The main course of the meal was tethered in the back of the Landrover, being completely unaware of what the future held for her!

Water was carried in hog skins so that coffee could be prepared and the cooks had their knives sharpened. We were going to the outer fringes of the tribal region so attack from neighbouring tribes and nationalists was a distinct possibility.

The journey started early next morning before the sun rose too high in the sky so that we could get shelter from it, at the huge boulder you see here. Our day out was to include a sumptuous meal which would be slaughtered and cooked on site. The main course of the meal was tethered in the back of the Landrover, being completely unaware of what the future held for her!

Water was carried in hog skins so that coffee could be prepared and the cooks had their knives sharpened. We were going to the outer fringes of the tribal region so attack from neighbouring tribes and nationalists was a distinct possibility.

Alan completed his mission of confirming that all was well with the South Arabian Federation which would be supported by the UK forces even after our departure. However, whilst we had been out of communication with the outside world little did we know that the Foreign Secretary, George Brown, had spelt out Aden’s future in that he said that independence for South Arabia would be granted on 9th January 1968 but that in departure from the Government’s policy of military assistance with ground forces then - no support – instead after Conservative opposition badgering the Government, he relented, and offered a force of Vulcan bombers with conventional weapons which would be available to assist the Federation, based on the island of Masirah. The bombers would be supported by a strong naval force in South Arabian waters. Our departure from Nisab and the Upper Aulaqi tribe was imminent. We returned to Khormaksar and re-established our lives in our respective jobs.

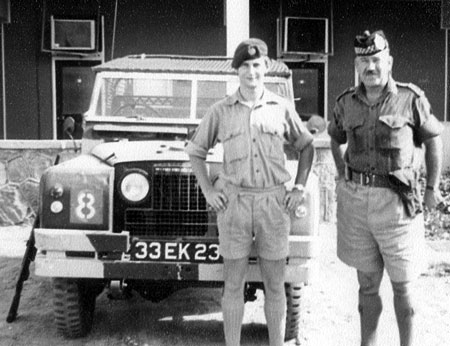

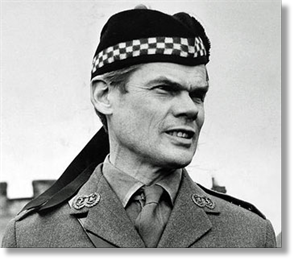

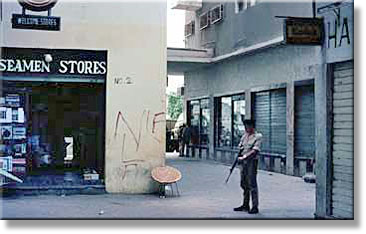

I was commanding a patrol controlling a checkpoint on the coastal road from Khormaksar to Crater, stopping all traffic apart from service on duty going into the district. As there had been a recent fire-fight traffic was sparse. I noticed two Landrovers, one with a commander’s pennant, approaching from the Crater region. I called to my scratch team of RAF tradesmen operating as soldiers to warn them of a senior officer approaching and to look smart. The lead LR arrived and out stepped Lt Col Colin Mitchell of the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders (AKA: “Mad Mitch”). I saluted whereupon two shots from across the bay aimed at us tore through the air between Col Mitchell and myself at head height and struck the cliff on the other side of the road splintering the rock face but no damage to us! The good Colonel said, “I think I’ve outstayed my welcome!”

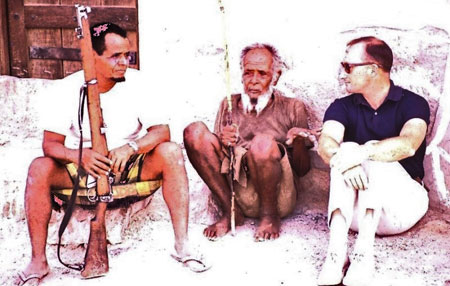

Since I retired I searched the internet and to my amazement found news of Alan D’Arcy. He was a member of the British Yemeni Society and takes parties to Aden each year. I contacted him by e-mail and at his request sent him pictures of our time in tribal areas – he was amazed with these pictures for he explained that the tribal leaders and their henchmen had been wiped out by NLF insurgents after we left. The Naib managed to get his heavily pregnant wife out of the country to Saudi Arabia – she escaped just before he was summarily executed with the rest of his tribal henchmen. Alan told me that the Naib’s wife had a son and now that he was mature he had been asked to return to the Yemen and resume the leadership of the Upper Aulaqi which he did, and Alan showed him and his tribal brothers pictures of their fathers whom they had never seen.

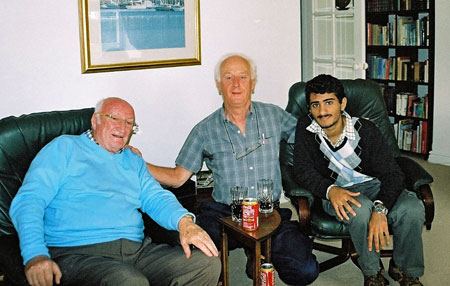

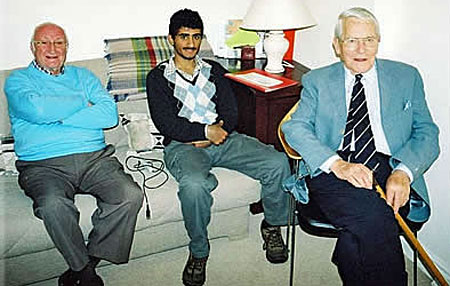

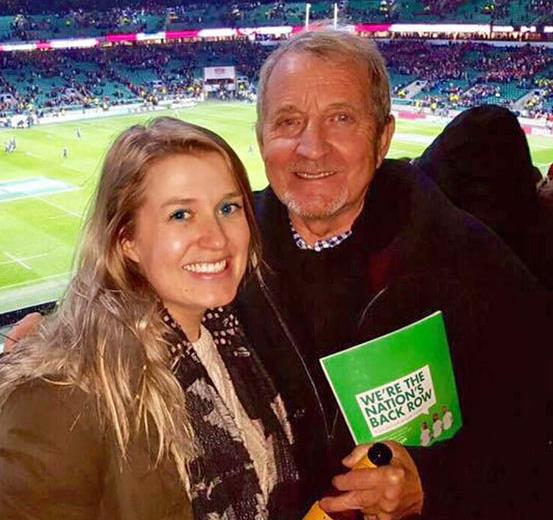

It was with certain excitement that I waited on Sunday 12th July 2009 for the arrival of my good friend Alan D’Arcy whom I last saw in Aden some 44 years ago, accompanied - on this occasion - by Mohammed Awadh the grandson of one of those Arab leaders that were highlighted in my “Aden Days” article which you will have seen.

Mohammed is a 19 year old student at the Pearson College on Vancouver Island Canada. After his studies there, he may well do a university course on Arabic studies in Britain before returning to the Yemen to take leadership of his tribal region north of Aden.

As he explained, his grandfather’s generation were all executed when the communist insurgents swept into Aden after we, the British, had left and this laid the way for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) forces – the Russians - to move in unhindered.

Alan had asked me if Air Vice Marshal Riseley-Pritchard RAF (Rtd) - one time the principle medical officer of the RAF - who lived locally (to me) could attend as he had been in Aden when we were both there and had also accompanied Alan in recent years visiting tribal leaders who were sick. I, of course, accepted and the photograph shows the principle players in my office.

As he explained, his grandfather’s generation were all executed when the communist insurgents swept into Aden after we, the British, had left and this laid the way for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) forces – the Russians - to move in unhindered.

Alan had asked me if Air Vice Marshal Riseley-Pritchard RAF (Rtd) - one time the principle medical officer of the RAF - who lived locally (to me) could attend as he had been in Aden when we were both there and had also accompanied Alan in recent years visiting tribal leaders who were sick. I, of course, accepted and the photograph shows the principle players in my office.

Mohammed also explained that I possessed amongst my 35mm slides precious pictures depicting his country’s history which he was profoundly thankful when I gave him my total holding of slides of the Aulaqui Tribe of Arabs. As I have most of them on my PC I don’t mind if I never see them again. ~ Charles

Five Decades Ago

Two years on the barren rocks of Aden -

one of the last outposts of the British Empire

one of the last outposts of the British Empire

Thomas P. Iredale

From: Thomas Iredale, Heidelberg

Subject: Memories of Aden

Subject: Memories of Aden

Discovery

Reading an article about Arthur Rimbaud, a 19th century French poet, in a German newspaper, I noticed that it mentioned that the gentleman had worked as a coffee trader in Aden. More specifically he was in Steamer Point from 1880. I then looked up the various details on the Internet and came across the website of Aden Airways. This site provided a great deal of information on the history of Aden and had many links to other websites dealing with this country. Here I found out about the railway! Reading the contents of the website and the contributions by people who had also been stationed there (military or civil) is why I started to focus on Aden. Before I begin, by the way, the railway was dismantled in 1930 because it lost money and therefore its place in the subsequent history of Aden faded. But here’s the full story:

Yes, there was a railway in Aden!

As early as 1906, a light railway from Aden to Dhala (Dthala) had already been under consideration for some time but nothing had materialised. Mr Cowasjee Adenwalla Dinshaw, (a Farsi gentleman, originally from Bombay, was a businessman in Aden), won the concession to build and operate the 120 km proposed rail link from Aden to Dhala after successfully negotiating a deal with the Sultan of Lahej, who would receive a 4% commission on the profits of the line plus one penny per square (?) of area taken by the line. The first 60km stage of the line was to extend from Aden to Nobet Dukeim. It seems, however, that the railway plan, for some reason, did not materialise.

Some years later in 1915, the CRE (Commander, Royal Engineers) requested permission to lay down a light railway from Aden to Sheikh Othman to supply the British forces fighting against the Turks, with the intention of extending it to Lahej once it was back in British hands. Approval was given and a 1000 mm gauge military railway was built by the Royal Engineers. By December (1915) work was completed on the new railway, providing a quick and efficient way to move troops and equipment to the Sheikh Othman defences.

In 1919, the Aden Government approved the extension to Lahej. The 46.3 km line was made available for public traffic in 1922. Aden was at this time still under the control of Bombay as part of the British Empire and materials for the railway were sourced from the Bombay, Baroda & Central India Railway (BBCIR) and the Eastern Bengal Railway (EBR). The Arabian system was operated by the North Western Railway (NWR) of India under one of its officers, who was designated Engineer-in-Charge. The railway carried passengers, grass, charcoal, green vegetables, potatoes, skins and other goods, and also large quantities of water for the army outpost at Sheikh Othman, which included a mobile force of cavalry and a camel corps.

Some years later in 1915, the CRE (Commander, Royal Engineers) requested permission to lay down a light railway from Aden to Sheikh Othman to supply the British forces fighting against the Turks, with the intention of extending it to Lahej once it was back in British hands. Approval was given and a 1000 mm gauge military railway was built by the Royal Engineers. By December (1915) work was completed on the new railway, providing a quick and efficient way to move troops and equipment to the Sheikh Othman defences.

In 1919, the Aden Government approved the extension to Lahej. The 46.3 km line was made available for public traffic in 1922. Aden was at this time still under the control of Bombay as part of the British Empire and materials for the railway were sourced from the Bombay, Baroda & Central India Railway (BBCIR) and the Eastern Bengal Railway (EBR). The Arabian system was operated by the North Western Railway (NWR) of India under one of its officers, who was designated Engineer-in-Charge. The railway carried passengers, grass, charcoal, green vegetables, potatoes, skins and other goods, and also large quantities of water for the army outpost at Sheikh Othman, which included a mobile force of cavalry and a camel corps.

To carry water, the railway was extended in 1920 to Hassaini Gardens, 13 kms north of Lahej. The Terminal Building in Maalla also housed the Maalla Sub-Post Office which opened in 1922 and closed seven years later, simultaneously with the closure of the railway in 1929. The railway had until that time carried mail. It has been suggested there were 7 locomotives in operation but this number seems rather exaggerated. Upkeep of the railway proved very expensive. £41,707 was outlaid since construction started in 1915 up to 31st March 1920. The operation was not a viable, commercial proposition; the line was closed in 1929 and dismantled in 1930.

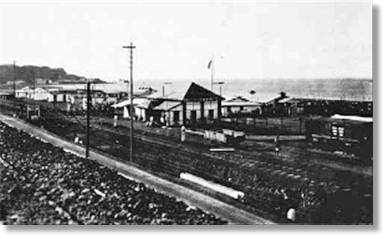

One of the locomotives in Maalla

Railway station at Maalla

On 19 January 1839, the British East India Company landed Royal Marines at Aden to secure the territory and stop attacks by pirates against British shipping to India. The port lies about equidistant from the Suez Canal, Bombay (now Mumbai), and Zanzibar, which were all important British possessions. Aden had been an entrepôt and a way-station for seamen in the ancient world. There, supplies, particularly water, were replenished, so, in the mid-19th century, it became necessary to replenish coal and boiler water. Thus Aden acquired a coaling station at Steamer Point and Aden was to remain under British control until 1967.

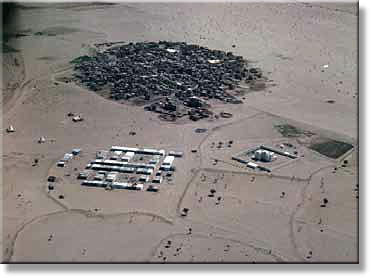

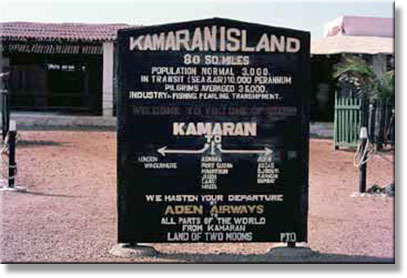

Until 1937, Aden was governed as part of British India and was known as the Aden Settlement. Its original territory was enlarged in 1857 by the 13 km² island of Perim, in 1868 by the 73 km² Khuriya Muriya Islands, and in 1915 by the 108 km² island of Kamaran. In 1937, the Settlement was detached from India and became the Colony of Aden, a British Crown colony. The change in government was a step towards the change in monetary units seen in the stamps illustrating this article. When British India became independent in 1947, Indian rupees (divided into annas) were replaced in Aden by East African shillings. The hinterland of Aden and Hadhramaut were also loosely tied to Britain as the Aden Protectorate which was overseen from Aden. After the Suez Crisis in 1956, Aden became the main location in the region for the British.

Until 1937, Aden was governed as part of British India and was known as the Aden Settlement. Its original territory was enlarged in 1857 by the 13 km² island of Perim, in 1868 by the 73 km² Khuriya Muriya Islands, and in 1915 by the 108 km² island of Kamaran. In 1937, the Settlement was detached from India and became the Colony of Aden, a British Crown colony. The change in government was a step towards the change in monetary units seen in the stamps illustrating this article. When British India became independent in 1947, Indian rupees (divided into annas) were replaced in Aden by East African shillings. The hinterland of Aden and Hadhramaut were also loosely tied to Britain as the Aden Protectorate which was overseen from Aden. After the Suez Crisis in 1956, Aden became the main location in the region for the British.

Federation of South Arabia and the Aden Emergency

In order to stabilise Aden and the surrounding Aden Protectorate from the designs of the Egyptian backed republicans of North Yemen, the British attempted to gradually unite the disparate states of the region in preparation for eventual independence. On 18 January 1963, the Colony of Aden was incorporated into the Federation of Arab Emirates of the South against the wishes of North Yemen. The city became the State of Aden and the Federation was renamed the Federation of South Arabia (FSA). An insurgency against British administration known as the Aden Emergency began with a grenade attack by the communist’s National Liberation Front (NLF), against the British High Commissioner on 10 December 1963, killing one person and injuring fifty, and a “state of emergency” was declared.

In 1964, Britain announced its intention to grant independence to the FSA in 1968, but that the British military would remain in Aden. The security situation deteriorated as NLF and FLOSY (Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen) vied for the upper hand. In January 1967, there were mass riots between the NLF and their rival FLOSY supporters in the old Arab quarter of Aden town. This conflict continued until mid February, despite the intervention of British troops. During the period there were as many attacks on the British troops by both sides as against each other culminating in the destruction of an Aden Airlines DC3 plane in the air with no survivors.

In 1964, Britain announced its intention to grant independence to the FSA in 1968, but that the British military would remain in Aden. The security situation deteriorated as NLF and FLOSY (Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen) vied for the upper hand. In January 1967, there were mass riots between the NLF and their rival FLOSY supporters in the old Arab quarter of Aden town. This conflict continued until mid February, despite the intervention of British troops. During the period there were as many attacks on the British troops by both sides as against each other culminating in the destruction of an Aden Airlines DC3 plane in the air with no survivors.

From “Around the World in 80 Days”

by Jules Verne (1825-1905)

“….the next day they put in at Steamer Point, north-west of Aden harbour, to take in coal. This matter of fuelling steamers is a serious one at such distances from the coalmines; it costs the Peninsular Company some eight hundred thousand pounds a year. In these distant seas, coal is worth three or four pounds sterling a ton. The “Mongolia” had still sixteen hundred and fifty miles to traverse before reaching Bombay, and was obliged to remain four hours at Steamer Point to coal up. ….Mr. Fogg and his servant went ashore at Aden to have the passport again visaed….”

by Jules Verne (1825-1905)

“….the next day they put in at Steamer Point, north-west of Aden harbour, to take in coal. This matter of fuelling steamers is a serious one at such distances from the coalmines; it costs the Peninsular Company some eight hundred thousand pounds a year. In these distant seas, coal is worth three or four pounds sterling a ton. The “Mongolia” had still sixteen hundred and fifty miles to traverse before reaching Bombay, and was obliged to remain four hours at Steamer Point to coal up. ….Mr. Fogg and his servant went ashore at Aden to have the passport again visaed….”

Some historical background

On 30 November 1967, British troops were evacuated, leaving Aden and the rest of the FSA under NLF control. The Royal Marines, who had been the first British troops to arrive in Aden in 1839, were the last to leave — with the exception of a Royal Engineer detachment.

The departure of the High Commissioner of Aden, Sir Humphrey Trevelyan, from Khormaksar on 28 November 1967. The Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, Admiral Le Fanu, is seen in the foreground.

Exit the Royal Marines and with them, the Empire

Privileged:

Falling into this category were all the other officers and civilians of officers’ status. If married and accompanied, all their accommodation was comfortable and serviced.

As the people in this category were generally in the younger age group and amongst all categories, there was probably more going on for them in the social world.

Unaccompanied, a single officer lived in the Officers’ Mess and enjoyed a watered-down version of their married counterparts. Access to the “watering holes” of the privileged was restricted to the appropriate category where a downward mobility was always possible but never an upward one, without a specific invitation, which was probably extremely rare.

Falling into this category were all the other officers and civilians of officers’ status. If married and accompanied, all their accommodation was comfortable and serviced.

As the people in this category were generally in the younger age group and amongst all categories, there was probably more going on for them in the social world.

Unaccompanied, a single officer lived in the Officers’ Mess and enjoyed a watered-down version of their married counterparts. Access to the “watering holes” of the privileged was restricted to the appropriate category where a downward mobility was always possible but never an upward one, without a specific invitation, which was probably extremely rare.

Privileged status: this is not from Aden, but from the days of the Raj in India

The colonial system still flourished: Long live the British Empire!

In varying degrees, life among the British population - I think I’m safe in saying here - both military and civil was categorised according to status. Broadly speaking, the categories were as follows:

Most privileged status:

General, flag and air rank; high political appointments; their wives and dependents. Surrounded by servants both local civil and service, they lived a life of splendid luxurious isolation in their villas, which were all located in the more salubrious (and guarded) areas around Steamer Point.

They had universal access to everything Aden and neighbouring countries had to offer: sea and land transportation was provided almost on-call. In other words, they walked on water! All those below this exulted status deferred and served in the traditional British manner; these were the colonial royalty.

Very privileged:

These were senior service officers (Group Captains, Colonels, Wing Commander’s and Lieutenant Colonels) and civilians, who were awarded similar status according to their job, as well as their wives and children. They were more in touch with the day-to-day routine of life on say RAF Khormaksar with all its attendant activities and occurrences. They did not live in splendid isolation, but had well-appointed, very comfortable and segregated residences. Their needs were attended by local and Service staff and they had access to virtually all the facilities Aden had and could organise transportation to a limited degree. These were the colonial aristocrats.

Most privileged status:

General, flag and air rank; high political appointments; their wives and dependents. Surrounded by servants both local civil and service, they lived a life of splendid luxurious isolation in their villas, which were all located in the more salubrious (and guarded) areas around Steamer Point.

They had universal access to everything Aden and neighbouring countries had to offer: sea and land transportation was provided almost on-call. In other words, they walked on water! All those below this exulted status deferred and served in the traditional British manner; these were the colonial royalty.

Very privileged:

These were senior service officers (Group Captains, Colonels, Wing Commander’s and Lieutenant Colonels) and civilians, who were awarded similar status according to their job, as well as their wives and children. They were more in touch with the day-to-day routine of life on say RAF Khormaksar with all its attendant activities and occurrences. They did not live in splendid isolation, but had well-appointed, very comfortable and segregated residences. Their needs were attended by local and Service staff and they had access to virtually all the facilities Aden had and could organise transportation to a limited degree. These were the colonial aristocrats.

All the rest:

Senior non-commissioned officers and civilians of this status enjoyed a status which enabled them to live a relatively comfortable and carefree life, without the class restrictions and social responsibilities of their officer counterparts, which have been mentioned above. The Sergeants had their own mess and their own beach; Corporals enjoyed a better status than airmen or private soldiers. Not many of the married corporals were accompanied, but those who were enjoyed pleasant serviced accommodation either on or off base. The airmen and private soldiers were all classified as BORs which means “British Other Ranks”. Their access to any place off-base was regulated by a sign outside an establishment, which said “Out of Bounds to BOR”. Even if you were a BOR, why couldn’t you go into a civilian establishment in say, Steamer Point, if correctly dressed, behaved yourself and could also afford it?

Senior non-commissioned officers and civilians of this status enjoyed a status which enabled them to live a relatively comfortable and carefree life, without the class restrictions and social responsibilities of their officer counterparts, which have been mentioned above. The Sergeants had their own mess and their own beach; Corporals enjoyed a better status than airmen or private soldiers. Not many of the married corporals were accompanied, but those who were enjoyed pleasant serviced accommodation either on or off base. The airmen and private soldiers were all classified as BORs which means “British Other Ranks”. Their access to any place off-base was regulated by a sign outside an establishment, which said “Out of Bounds to BOR”. Even if you were a BOR, why couldn’t you go into a civilian establishment in say, Steamer Point, if correctly dressed, behaved yourself and could also afford it?

Three-quarters of Middle East Command aircraft were based at Royal Air Force Khormaksar, its main flying station. Khormaksar was a joint user airfield – that is, it was Aden’s civil airport as well as an RAF station, the RAF providing airfield, navigational, meteorological and communications facilities to the many civil airlines operating from and through Aden. Broadly, RAF Khormaksar’s tasks could be grouped under two main headings – tactical and transport.

On the tactical side, its main jobs were to defend Aden and the Protectorates from external attack and to maintain law and order within the territory. The units based there were also called upon to operate, as required, elsewhere in the Command’s area of responsibility. Also included in this side of its duties were control over sea communications within the area, responsibility for the search and rescue organisations in the Command and the maintenance of airfields, navigation aids and facilities extending from Hargeisa in Somaliland to Masirah Island at the entrance to the Persian Gulf.

On the tactical side, its main jobs were to defend Aden and the Protectorates from external attack and to maintain law and order within the territory. The units based there were also called upon to operate, as required, elsewhere in the Command’s area of responsibility. Also included in this side of its duties were control over sea communications within the area, responsibility for the search and rescue organisations in the Command and the maintenance of airfields, navigation aids and facilities extending from Hargeisa in Somaliland to Masirah Island at the entrance to the Persian Gulf.

Royal Air Force Khormaksar was established in Aden in 1917 and then enlarged in 1945 as the British spread their influence deeper into the Arabian Peninsula. In 1958, a state of emergency was declared in Aden as Yemeni forces occupied nearby Jebel Jehaf and RAF squadrons were involved in action in support of the British Army. In the 1960s, during operations around Rhadfan, the station reached a peak of activity, becoming overcrowded and attracting ground attacks by rebels. It was the base for nine squadrons and became the RAF's busiest-ever station as well as the biggest staging post for the RAF between the United Kingdom and Singapore.

In 1966, the newly elected Labour government in the United Kingdom announced that all forces would be withdrawn by 1968. Khormaksar played a role in the evacuation of British families from Aden in the summer of 1967. The station closed on 29 November 1967, becoming Aden International Airport.

In 1966, the newly elected Labour government in the United Kingdom announced that all forces would be withdrawn by 1968. Khormaksar played a role in the evacuation of British families from Aden in the summer of 1967. The station closed on 29 November 1967, becoming Aden International Airport.

RAF Khormaksar

Aspects which have stayed in my mind

When I arrived to begin my two year tour at RAF Khormaksar, I was 20 years old and single, had been in the Air Force for 22 months and had attained the rank of Senior Aircraftsman (SAC). The flight on a Britannia took twelve hours. All the accounts that I have read about first impressions of Aden, open with the remark that stepping out of the aircraft was like “walking into an oven going full blast.” For me, it wasn’t any different; the heat was awesome, the average mean temperature in November was 28°C. All new arrivals stood out, being pale and were the subject of playful derision by those already there. The usual cries of “moonie” and “Get your knees brown, lad” echoed in our ears. After a few weeks, we new arrivals also blended into the scenery. It was my good fortune that a friend of my father’s and a neighbour at RAF Headley Court, Flight Sergeant Alan Keech was also there and within the first few days he helped me to settle down. He had me order “proper” KD, lightweight civvie trousers and shirts from the tailor in his workshops at 131 Maintenance Unit. He also suggested that I join the Theatre Club.

There were twenty beds to a room when I moved into the Suppliers' block and lying reading on one of the beds was an old school chum, Mick Fox. We were both in the same fifth form at St Mary’s College in Crosby, Liverpool. I had not seen him since 1959 and did not know that he had also joined the Air Force. He was an SAC Supplier Accounting like I was and worked in the Stock Control and Accounting Squadron (SCAS) in Supply Wing. Through him, I was able to get the lowdown on how things were and he gave me lots of tips, because he’d been there for quite some time already.

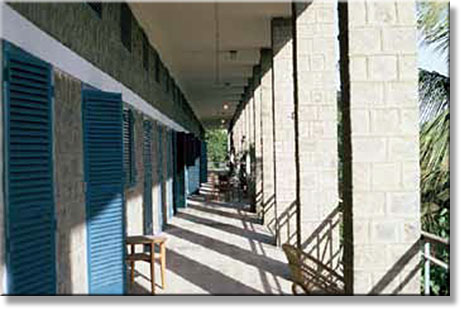

No longer can I remember the number of the block, which housed the Supply Wing personnel. It was however situated on the right hand side of the road that came up from the gate, where the bus and taxi stops were, past the Officer’s Mess to the main gate of the active part of RAF Khormaksar. The block is still there according to Google Earth. It was well-built, with two floors, having wings on either side of a central stairwell to the first floor. Each wing had twenty bedspaces, ten on each side. Each space was equipped with an iron bedstead, big locker and a small one. On every floor, there was a water cooler, which was a good thing. All furniture was standard Air Force issue, not made locally. The ceilings were high and there were three or four overhead fans, which never broke down. There were wide balconies on either side of the rooms with both glass and louvre doors on the outside. It was OK in the cool season (October-March), but in the hot season took some getting used to.

The Bristol Britannia - the passenger seats in RAF transport aircraft were all backward facing

Life can’t be all that bad! The author lying on his bed - note the tailor-made KD

Each room had a bearer or chai-wallah, who made the beds, collected and delivered laundry, cleaned shoes and kept the place clean. He also made tea and sandwiches and lived from the money he made from us. How much, I no longer recall. He had a small room adjoining the dormitories, where he kept his tools of the trade. By and large, everyone in the block got along with each other. As we worked from seven in the morning until one pm, the afternoons were free. I can remember some marathon games of Monopoly, real cliff-hangers! Some played cards, but I wasn’t into that. Then sometime at the end of 1964, the blocks were due to be air-conditioned, which would really be luxurious in the hot season. The drawback was, that everyone in a room had to find alternative accommodation, whilst the ducting was being installed in his room. I was very fortunate to be able to bunk in with my two buddies Cpl Terry Fowler and Cpl Gerry (surname not remembered), who had their own room downstairs in the block. But bed only – lockers had to stay upstairs, so I had to go up to the first floor to change and get dressed. This all lasted a few weeks but I don’t recall any big “switch-on” euphoria, when the air-conditioning was switched on.

Supply Control and Accounting Squadron (SCAS)

I was posted to Supply Wing at RAF Khormaksar, possibly the largest RAF station in the world and started to work in Stock Control. In SCAS, my job was to take the telephone orders for items required from authorised users. An authorised user was an NCO or officer, responsible for an inventory or section. Among the hundreds, if not thousands of items which fell into my remit was ground equipment (section 4). I cannot recall the others.

There were five of us doing this in my particular section. There were three sections altogether. The stock control cards, called Form 1640s – one card for each item – were in a bin on wheels next to my desk. This was also close to one of the air conditioning units set into the wall, which made SCAS quite a pleasant place to work in, when you consider the climate. When a call came, I would write down all the items requested, pull the 1640s and check them for stock. If we had stock, I wrote out the preprinted voucher (a Form 674 for “Issue”), put it into a folder with the card(s) and passed it on for vetting to the Corporal, who passed it on the Sergeant for approval and issue. Part of the Form 674 went on its way to where the stock was held and the other part went with the F 1640 to be processed in the machine room. That is an easy description, but it was in fact somewhat more complicated and not madly exciting.

My Corporal’s name was “Taff” and obviously he was a Welshman, but I can’t remember his full name. My Sergeant was John Shaw, a strict and very fair person who smoked a pipe, who had been in the RAF for a fair while and knew the Supply business inside out. One of the Sergeants responsible for another section was Des Strongman. I don’t recall the name of the other one, but he had a very distinctive moustache.

There were five of us doing this in my particular section. There were three sections altogether. The stock control cards, called Form 1640s – one card for each item – were in a bin on wheels next to my desk. This was also close to one of the air conditioning units set into the wall, which made SCAS quite a pleasant place to work in, when you consider the climate. When a call came, I would write down all the items requested, pull the 1640s and check them for stock. If we had stock, I wrote out the preprinted voucher (a Form 674 for “Issue”), put it into a folder with the card(s) and passed it on for vetting to the Corporal, who passed it on the Sergeant for approval and issue. Part of the Form 674 went on its way to where the stock was held and the other part went with the F 1640 to be processed in the machine room. That is an easy description, but it was in fact somewhat more complicated and not madly exciting.

My Corporal’s name was “Taff” and obviously he was a Welshman, but I can’t remember his full name. My Sergeant was John Shaw, a strict and very fair person who smoked a pipe, who had been in the RAF for a fair while and knew the Supply business inside out. One of the Sergeants responsible for another section was Des Strongman. I don’t recall the name of the other one, but he had a very distinctive moustache.

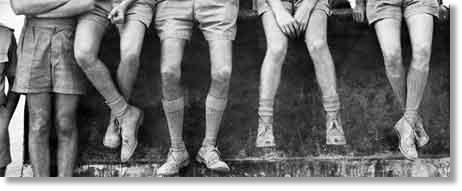

“An inch and a half above the knee”

Not much when you think about an inch and a half, yet this small dimension caused more than a ripple to the hundreds of Air Force personnel stationed in Aden during the mid-1960s. The legendary WW2 fighter pilot ace, “Johnnie” Johnson was the Air Officer Commanding (AOC) Air Forces Middle East (AFME), and in that capacity was “Lord of the Rings” in Aden. I could never quite fathom out, why this particular bee with the “1 ½ inches above the knee” got into his bonnet, but the effects of the edict were wide-ranging! I presume that somewhere in the dress regulations for the Royal Air Force, there must have been a detailed description concerning how KD had to be worn. Having said all that, he may well have had a point. The hemlines - if I may call them that – of the shorts worn by RAF personnel did vary between quasi bell-bottoms and mini-skirts. As the AOC, it was his duty to see that regulations were adhered to. After the order came out, there was a rush to the tailors (for the poor unfortunate unmarried) to have the shorts’ hemlines lowered to the required length. It was most amusing, because you could see the colour difference of the let-down material. Honestly speaking, it seemed to me to be a bit ridiculous, for by and large there was very little, which was “inappropriate”. Nevertheless, the tailors, most of whom were Indians, profited from this unexpected surge in turnover.

Starched stiff as a board

I recall another bee that the AOC had in his bonnet. He was very keen on stiffly-starched KD. There was the annual AOC’s inspection, preceded by a parade (in the very early hours of the morning, thank heaven) at Khormaksar. He went down the ranks, stopped in front of an airman, remarked on his Khaki Drill (KD) uniform, which had been starched stiff as a board, complimented him and asked him, how much it cost – 50 cents or whatever. The starching was usually so extreme, that you had to prise open the sleeves to put it on. Needless to say, after a day’s wear in that climate, especially in summer, the starched uniform KD was limp. Most of us wore our issue KD, suitably starched, only for parades, but I had 2 sets of tailor made KD, which were very comfortable.

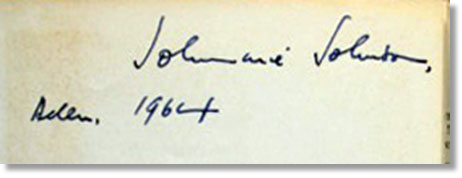

Still on the subject of Johnnie Johnston, in 1964 he had a book published, called “Full Circle” about the evolution of air fighting.

A bookshop in Crater was selling this book and being curious (and a little impressed) I bought one and found that it had been signed by the man himself. I still have the book 50 years later. The jacket is a bit torn, but otherwise in very good condition.

A bookshop in Crater was selling this book and being curious (and a little impressed) I bought one and found that it had been signed by the man himself. I still have the book 50 years later. The jacket is a bit torn, but otherwise in very good condition.

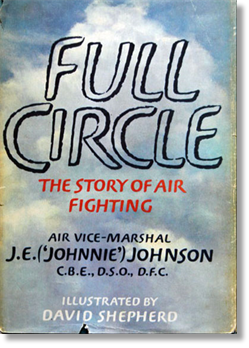

“Full Circle”

Food

My recollection of the food in the Airmen’s Mess is a bit hazy as I use to dread going there, because it was so stifling hot in both the dining and the serving area. To give them their due, the cooks did not have an easy time in the heat, but the menus seemed to be all traditional UK-type mess food, heavy and basically unsuitable to the climate. What does stick in my mind is that when fresh grapefruit was served at breakfast, I was up early to get some before it all went. Otherwise, I never went to breakfast, was content with a cup of tea from the bearer and then had some rolls at the Supply Wing Stim bar. I never found out if there was any truth in the rumour, that the Mess cooks put bromide into the tea! Eating out was on the whole quite good. I remember the small restaurant in the shopping centre not far from the camp gates. On the other (back) entrance to the camp, there was a fish and chip wagon, which was very well patronised and I believe, is still there, although now it seems to serve hamburgers.

Uniform

The usual footwear in (or out of) uniform was the desert (or Bondu) boot, made of suede leather with a crepe sole. They were actually very comfortable, but you had to buy them yourself. I even had a pair custom-made (but with leather soles) by an Indian cobbler, who drew the outline of my bare foot on a piece of paper. When I came to wear them they were a bit tight, because of course, these boots were worn with socks. So it was not exactly the best investment I had ever made. The RAF issue black shoes were not really ideal for tropical wear, as they were heavy and a tighter fit than the desert boots.

Flip-flops were omnipresent in the off-duty hours and they were practical and comfortable. The long socks we wore were made mainly of nylon, which to modern thinking is not a very healthy idea, but with the help of Mycota or whatever the anti-athlete’s foot powder was called, feet problems were kept to a minimum. The beret was a bit stupid, because it was not tropical weight and afforded no full protection from the sun. My dad was issued with a toupee when he was posted to Egypt in 1938 and these days, floppy sun hats have become accepted head wear. Of course, you had to take all your kit with you, when you are posted. Amongst my kit was a greatcoat, which I certainly didn’t need in that climate and for once, the Air Force made a sensible arrangement, whereby your greatcoat was vacuum-packed and held in storage for you. Then you were issued with a deficiency chit for “Greatcoats, Airman, 1”, which had to be produced when there was a kit inspection. I never knew what happened to it after I left, as I didn’t take it with me. Perhaps my greatcoat is still there!

Flip-flops were omnipresent in the off-duty hours and they were practical and comfortable. The long socks we wore were made mainly of nylon, which to modern thinking is not a very healthy idea, but with the help of Mycota or whatever the anti-athlete’s foot powder was called, feet problems were kept to a minimum. The beret was a bit stupid, because it was not tropical weight and afforded no full protection from the sun. My dad was issued with a toupee when he was posted to Egypt in 1938 and these days, floppy sun hats have become accepted head wear. Of course, you had to take all your kit with you, when you are posted. Amongst my kit was a greatcoat, which I certainly didn’t need in that climate and for once, the Air Force made a sensible arrangement, whereby your greatcoat was vacuum-packed and held in storage for you. Then you were issued with a deficiency chit for “Greatcoats, Airman, 1”, which had to be produced when there was a kit inspection. I never knew what happened to it after I left, as I didn’t take it with me. Perhaps my greatcoat is still there!

Stim bar

Each squadron had their own Stim bar and they varied in the services provided, depending on who was running it. They were all equipped with fridges and other facilities for preparing food and drink. By and large, I never heard of any hygienic problems. Ours was housed, I think, in a modified aero engine packing case – or at least this was the basis. The name came from a soft drink brand. Now a Stim bar was an interesting business model. It was run by the wing or section and all profits stayed there. As there was money involved, it had to be overseen by a commissioned officer.

Nairobi

I managed to get away to Nairobi to visit my family, as my father was on an accompanied tour at RAF Eastleigh. The flight was courtesy of a 205 Squadron Argosy. The co-pilot I remember very well, as he was a very friendly young chap called Martin Willing – a Flying Officer at that time. He wore a red baseball cap (of which you see millions these days) which of course clashed with his greenish flying suit. I later met him again, when I was OC Air Movements Squadron at RAF Benson in 1970 and he was still flying Argosies. We still chuckled at my red hat recollection six years later.

Photography

It was Roger, who taught me how to develop and print black and white films. My interest in photography continues to this day, but it is no longer film, but digital. I bought an enlarger and all the other stuff you needed to print negatives, but I had the films themselves developed locally. I took over the bearer’s room (he had already gone home for the night), blacked it out and set up the enlarger. Then I mixed the developing and fixing chemicals and got started. There was no fan in the room; the window was blacked out and you can probably imagine the stifling air already! However, I persevered and was not too displeased with my results. Pete Bagley – SAC and drummer with a band called “The Casuals”, which had a regular series of bookings, gave me my first commercial photography job. I soon discovered that I still had a lot to learn about taking action shots on stage outdoor in the evening. Sadly, despite having taken possibly hundreds of pictures, I no longer have them any more.

Charity drives

One of the nicer things about the Services is their willingness to contribute to charity. This takes many forms from sponsored events, lotteries and cash drives. Whilst I was in SCAS, I helped organise a charity drive for the “Wireless for the Blind” fund. I created a map of the world, showing all the countries from UK to Aden and a flight route from Aden to the UK, total distance 3,600 miles, divided into segments of 100. An aeroplane was affixed to the corresponding segment, representing the amount of cash we had raised. This translated as one EAS per flight mile. We collected EAS 3,600 and accompanied by the beautiful Jane, daughter of an SNCO, Flt Sgt Thompson in SCAS, I went along to BFBS, where we were interviewed and handed over the cash for the “Wireless for the Blind” Fund.

Christmas

The first Christmas I spent there (1963) was on the beach, as I was too new to have the kind of close friends who invited me for Christmas. The second Christmas in 1964, was spent with the family of a Warrant Officer from SHQ and Cpls Terry Fowler and Gerry (forgive me, your surname escapes me, as also the name of the WO). Not that I was particularly homesick or anything, but it was nice to be in a home and not in a barrack or clubhouse or mess. I did really appreciate this friendship, despite the disparity in rank again. The WO and his family had Married Quarters in the compound just outside the camp. We were there fairly often for a meal or drinks and sometimes we stayed over, as they had two spare bedrooms. The WO was later posted to RAF Innsworth and sometime after I was commissioned, I visited him and his wife there.

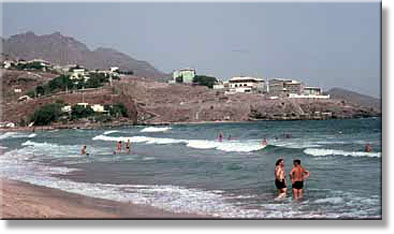

Snorkelling in Elephant Bay

Quite soon after I arrived, I bought a face mask, snorkel and a harpoon gun. I had noticed from earlier swims in the sea that there was a lot of fish around. I thought that I would try my hand at catching them.

Catching the fish, however, was not as easy as I had imagined. They were always too quick for me or more likely I was too slow for them. The only thing I distinctly remember catching was a squid. However, the problem I had was how to remove it, because its tentacles were entwined around the harpoon. With friends giving the usual bizarre advice, I finally decided to reload the harpoon into the gun and fire it into the air. This was done and when the harpoon line ran out, the squid continued on its maiden flight into the sea. This made me feel bad and shortly afterwards, I sold the harpoon to somebody else.

The stinking whale

One summer’s day in 1964, a whale went off course and erred into the shallow waters of Elephant Bay. It could not get back into deep water and I’m not sure if any rescue attempt was made or would have even been possible. The whale lay there, beached. Gradually, under the murderously hot sun and high humiditiy, the carcass began to decompose and the smell was carried by the sea breezes to those using the beach. It was an intense and disagreeable stench. Weeks, it seems, must have gone past before the smell subsided.

Being there and getting away

The tour of duty in Aden was 2 years and many had a chart on which they counted the days still to go and delighted in crossing of the “time served”. There was a name for it (Tourex or Blighty chart?), but it escapes me right now. I didn’t recall anymore who was there saying that they enjoyed it, but some were definitively better off there than others – at least in the financial sense. Depending on your rank and marital status, you got a “Local Overseas Allowance”, which was useful and of course, it was tax-free. Other things too were tax-free, like cigarettes and booze. BOR’s (British Other Ranks) (what a dreadful expression – very colonial!) could not buy spirits (by the bottle) – this was a privilege reserved for NCOs and officers.

Within the tour, you were entitled to one free air travel ticket to the UK (renown as LUKFREE). Most took this after the first year. There was also an entitlement to spend 14 days at the Silver Sands Resort, run by the Services, in Mombasa, Kenya. Due to my being sent home for the Officer and Aircrew Selection Board (OASC) at Biggin Hill during the May of my second year, I never went to Mombasa. For the OASC trip, I was allowed to tag on some leave in the UK and I spent it with my family in Headley Court. From hearsay, the Silver Sands sojourn seemed quite idyllic. It was said that when you arrived, you chose an African lady (or she chose you), who looked after you in all senses of the word during your stay. She was remunerated by her current “client” and took care of all the cooking, cleaning and laundry.

Within the tour, you were entitled to one free air travel ticket to the UK (renown as LUKFREE). Most took this after the first year. There was also an entitlement to spend 14 days at the Silver Sands Resort, run by the Services, in Mombasa, Kenya. Due to my being sent home for the Officer and Aircrew Selection Board (OASC) at Biggin Hill during the May of my second year, I never went to Mombasa. For the OASC trip, I was allowed to tag on some leave in the UK and I spent it with my family in Headley Court. From hearsay, the Silver Sands sojourn seemed quite idyllic. It was said that when you arrived, you chose an African lady (or she chose you), who looked after you in all senses of the word during your stay. She was remunerated by her current “client” and took care of all the cooking, cleaning and laundry.

Elephant Bay

Getting around

Prior to the increasing terrorist activities in 1965, life was quite bearable and you could travel freely within the areas, commonly frequented by us. That is to say, Khormaksar, Maalla, Crater, Steamer Point and Elephant Bay. I didn’t have a car and the majority of single personnel didn’t have one. So we went by taxi or bus. These latter vehicles generally had no windows, so that as long as you were moving, being inside the bus was bearable. They were somewhat antiquated, where they originally come from, I have no idea. By and large, they got you from A to B very cheaply. One day, I was in one going from Maalla to Steamer Point, when it had an accident with a car. The bus stopped, the Aden Police came and I had to go to the station and make a statement. I no longer remember any more details.

Local currency

For a long time, Aden was administered by the Raj in India and the local currency was rupees and annas. When India gained its independence in 1947, the local currency was changed to “East African Shillings”. Local pay was in this currency and you used it to pay for everything both in the Service facilities (e.g. NAAFI) or the local economy. I’m not quite sure about the changeover date, to dinars and fils, but remember distinctly a saying which was quite clever, namely that “I’ve had more fils, than you’ve had hot dinars!”

An Argosy lands in the sea

This was indeed a big crowd puller - the Argosy which ditched in the sea. I also went down a few times to have a look. Here are two accounts as to how this happened:

“While on crew training on 23rd of March 1964, Argosy XP 413 ditched in Aden harbour. Due to the prompt action of the engineering team it was recovered, dismantled and returned to Hawker Siddley Aviation in the UK on the 20th of June 1964 by surface transport. In the UK it was totally refurbished and transferred to 242 Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) on the 5th of May 1966.”

Roger Wilkins [Radfan Hunters Web Page] recalls: “We were driving in our little Fiat 600 along a road which bordered the inner harbour and as we rounded a bend there was an Argosy, for all the world like a flying boat, lying in the water not 50 yards from the shore.

Roger Wilkins [Radfan Hunters Web Page] recalls: “We were driving in our little Fiat 600 along a road which bordered the inner harbour and as we rounded a bend there was an Argosy, for all the world like a flying boat, lying in the water not 50 yards from the shore.

"It turned out that it was a ‘feathering’ classic. The Argosy (XP413 from 105 Squadron) had been up on training mission for a newly arrived pilot and one of the exercises was a practise engine failure on the approach to land at Khormaksar. The instructor pilot had shut down the port inner expecting the trainee pilot to feather that engine. Unfortunately in his anxiety to cope with the emergency the co-pilot feathered the port outer. The Argosy does not fly well on two engines particularly if they happen to be on the same side! As there was not enough time to relight the port inner or un-feather the port outer the Captain had no alternative but to ditch the Argosy in about three feet of water.”

The local population

If not all, then most of the Service personnel had little or no contact with the local Arab population beyond those who provided the usual services a major air base required. But the local population also included a large number of Indians, who had been there for a couple of generations. These people ran shops and businesses and I made friends with an Indian lad about my age called “Adi” Patel. His dad ran a fairly big shop in Steamer Point and they lived nearby or even above the shop. My mate, Arthur, who also worked in Supply, went along as well and it was quite a nice change to be in a different culture.

Haircut and shave, please

As far as I recall, the barbers were Indians and their shop was in or near the Airmens’ NAAFI. Prices were not exorbitant and hair tended to be worn short anyway. One day, I thought I would find out what it was like to be shaved by a barber. It seemed a bit funny, but I thought I’d give it a try anyway. In the chair, head tilted back the barber began lathering my chin. Then he honed his cutthroat razor on the strop and began to scrape my stubble. He was so efficient, that it was all over in five minutes flat. I don’t believe I thought it was the closest shave I’d ever had, but it was an experience - which I have never repeated since.

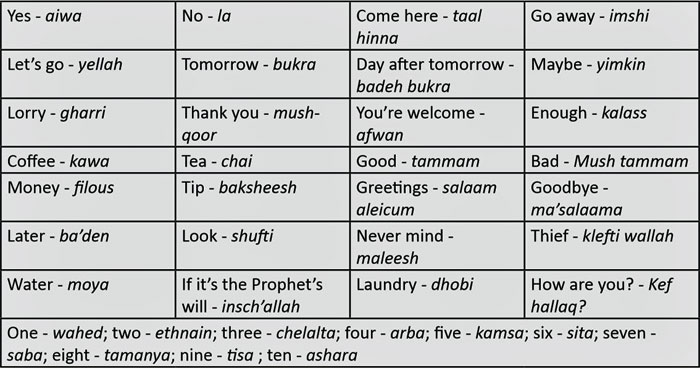

Arabic

For day-to-day contact with the Adeni population, many of whom spoke some English, we had a basic vocabulary of Arabic. Together with body language, signs and sometimes a picture, we seemed to muddle through with the following limited range of Arabic:

Hay fever adieu!

From the age of about ten, I dreaded sunny days in summer, when the grass pollen was in the air. Itchy eyes, runny nose and basically had to take shelter inside. I loved rainy days, then I could go out. Arriving in Aden, I entered a pollen-free zone, although I did not consciously register this fact. After a year’s sojourn in Aden, I went back to the UK on leave in the summer months and had no attacks of hay fever. After almost 2 years in Aden, I was completely cured and have never had any problems since. No one really thinks of Aden as a therapeutic location, but I am grateful for the fact that there were billions of grains of sand, but not a single grain of grass pollen!

A birthday to remember - the next day, anyway!

The 7th March 1964 was a Saturday and also my 21st birthday. As we worked on Saturday mornings, I invited a few friends to the Camel Club, which was across the road from the mess, for a few drinks. Well, we had a few drinks, everything was going well and I must admit I felt fine. Unbeknownst to me my drinks were being doctored….! With rum and Coke, it’s difficult for an occasional drinker (as I was then) to tell the difference in proportionate taste (strong Coke, this!). At another table, some lads had a pet monkey, which they fed with rum and Coke as well and it was actually quite funny to watch. Then all the lights around me went out and I knew nothing until I woke up in my bed the next morning. What was that saying: “Never again?”

Terrorism gathers pace

Chicken wire

As terrorist activities started to increase, am no longer sure if it was 1964 or 1965 – I remember being part of a detail to affix chicken wire to the outside of all the windows of the married quarters. The idea was to screen the windows, which were usually open (normal – as there was no air conditioning) against a terrorist lobbing a hand grenade through the window. So off we went – a pair of pliers to cut the chicken wire to size and a hammer and nails to secure it in place. I don’t remember how many windows I “secured”, but it was quite a few. I just hope that the residents appreciated our efforts!

Guard duty

Guard duty definitively put a mocker on my social life and that of almost everyone else in Aden. Security became ever tighter and restrictions to movements became severe during the latter part of 1965, when guard duty was significantly increased. During the early part of my stay, it wasn’t too onerous – maybe once a fortnight. “Buying” guard duties was a lucrative trade for those who had no outside interests. Those with an outside interest, like my friend Pete Bagley, who was the drummer in a band heavily booked by the Sergeant’s Mess, Corporals Club etc, could easily afford to pay someone to do his guard duty. How much it cost, I have no idea, but it was well worth it, if you had nothing better to do.

You went on your guard duty at 18.00 hrs. You reported to your detail, wherever that may have been and were issued with a Lee Enfield rifle, calibre .303 and five rounds of ammunition (ball) as well as the “yellow card”. This latter contained the circumstances when you could shoot your rifle (shoot to wound!). I no longer have a copy, but after you read what was written, it made you think twice of the dire consequences, before loosing off a round! After drawing your weapon and five rounds, you were divided into watches of two hours on and four hours off.

You went on your guard duty at 18.00 hrs. You reported to your detail, wherever that may have been and were issued with a Lee Enfield rifle, calibre .303 and five rounds of ammunition (ball) as well as the “yellow card”. This latter contained the circumstances when you could shoot your rifle (shoot to wound!). I no longer have a copy, but after you read what was written, it made you think twice of the dire consequences, before loosing off a round! After drawing your weapon and five rounds, you were divided into watches of two hours on and four hours off.

The Lee Enfield rifle weighed 4 kg and the magazine could hold ten rounds of .303 ammunition. It had a kick like a mule into your shoulder. Basically this rifle served the British Armed Forces during both World Wars and other conflicts since, until it was replaced by the FN rifle.

The shift system

First shift: 18:00-20:00; 24:00-02:00

Second shift: 20:00-22:00; 02:00-04:00

Third shift: 22:00-24:00; 04:00-06:00

I’m no longer sure how the shifts were allocated; the most unpopular shift was naturally 02:00-04:00. I think the sergeant in charge of the guard allocated the shift according to how he wanted – by calling for volunteers or arbitrarily allocating the slots as he wished. What was the best shift? All had their advantages and disadvantages. For me, there is no doubt that the 02:00-04:00 slot was the killer, as you had no “rhythm” in your body clock to operate at this hour of the morning! Between patrols, you could get your head down and young as we were, we could sleep anywhere. To be rudely awoken (not really – let’s face it – it was a system and nothing personal) shortly before two a.m. was awful, but it had to be done and so we staggered up, got our rifles and went out into the night.

Second shift: 20:00-22:00; 02:00-04:00

Third shift: 22:00-24:00; 04:00-06:00

I’m no longer sure how the shifts were allocated; the most unpopular shift was naturally 02:00-04:00. I think the sergeant in charge of the guard allocated the shift according to how he wanted – by calling for volunteers or arbitrarily allocating the slots as he wished. What was the best shift? All had their advantages and disadvantages. For me, there is no doubt that the 02:00-04:00 slot was the killer, as you had no “rhythm” in your body clock to operate at this hour of the morning! Between patrols, you could get your head down and young as we were, we could sleep anywhere. To be rudely awoken (not really – let’s face it – it was a system and nothing personal) shortly before two a.m. was awful, but it had to be done and so we staggered up, got our rifles and went out into the night.

We patrolled the hangar areas and around the aircraft parking areas in particular (please note: in the Royal Air Force, all aircraft are referred to as - AIRCRAFT – and not as planes, aeroplanes, kites or other derogatory forms of these magnificent machines that take to the air). So you slogged around your beat, with your .303 Lee Enfield on your shoulder (and it was heavy) together with your mate, as guard duty was always in pairs. Depending on who your mate was and the subjects you talked about, the time went quicker. In all the many guard duties that I did, I never had one incident, which caused me (or my buddy) to shoulder my rifle and fire – thank God! As an aside, doing guard, unpleasant though it may have been, was bearable because the night in Aden was relatively pleasant and in the cold season, even enjoyable – so called “Millionaire’s Weather”. I cannot remember what the stand-down regulations were after a guard duty. Whether you had to report for duty at 07:00 hrs the next morning as usual, I cannot remember!

Being realistic about terrorist threats

Something which does stick in my mind was a remark by a Rockape, as the members of the RAF Regiment were affectionately known, patrolling our segment in a Land Rover. We were near a “chowkidar” or guard/caretaker, who was brewing tea. He said to me: “Don’t trust him; don’t turn your back on him.” and drove on. I thought “What a load of bollocks, this old man had been there for all the times I had been doing guard”. In the light of the subsequent developments in terrorist techniques as we know today, the Rockape was right - and I was totally ignorant! But it was not embedded into our thinking of that time. I’m not sure exactly when this took place, but it must have been around the end of 1964 or the beginning of 1965.

The captured Ilyushin

Whilst doing rounds on guard duty, I do recall “guarding” the Egyptian Air Force Ilyushin 14 aircraft, which had acquired permanent visitor status out on the pan. It had a fascinating history as to why it was there.

In late 1964, somewhere “up-country”, the aircraft had accidentally landed at one of our forward air bases. Before the pilot realised his mistake and attempted to take off again, one quick-thinking Army captain (think about that: “quick-thinking” and “Army captain” - this is typical blue job’s disdain for brown jobs) drove his Land Rover in front of the aircraft, causing it to abort its take-off. To cut a long story short, the aircraft was brought back to Khormaksar, never flew again and was still there, I hear, when we pulled out in 1967. So that this bit of history does not fade into oblivion, (like the railway story) here is the full story as reported by Peter Pickering’s faithful research and his citation from the “Dhow” newspaper on the next page:

Refuelling

Sometime in 1965, the terrorist threat caused an increase in the amount of personnel sent to combat it. These reinforcements all came in by Air Transport Command aircraft (Britannias mainly) and chartered aircraft. The Supply Wing was also responsible for POL (Petrol, Oil and Lubricants) and this meant our chaps operated the petrol pumps for vehicles and the refuelling bowsers for aircraft. As three shifts were required, I was seconded to POL duties and began to work shifts. This was quite new to me and, in a way, a welcome change. However, you were always within the smell (or stink) of petrol, diesel, AVTAG, AVGAS AVTUR or whatever was at that point of delivery or back in the section building. The smell was everywhere, your body, your clothes, everything. Get some diesel on your good KD and it was ruined. Wearing Bondi boots with their crepe soles was very dangerous as you could slip if you weren’t careful. Most memorable and most scary was when I was on nights and some charter aircraft had to be refuelled. By and large, no big problem, I generally had to do the paperwork and get a receipt for the thousands of gallons we pumped into the aircraft.

Never volunteer!

Usually the bowser driver and the aircraft engineer took care of the refuelling process. On this particular night, however, the engineer of a Super Constellation complained about a back injury and suckered me into doing the actual refuelling. This entailed walking on top of the wing, opening the fuel intake (rather like filling a car), and holding the pistol grip of the fuel line into the tank until it was full. I’m not good at heights at the best of times and I had my Bondi boots on an ideal slide to oblivion, if any fuel spilled onto the wing. I was scared, really. This was something I should not have done and if anything had happened to me, then it would have been my own fault. Soft touch, but there again, I was always willing to help out where I could. Nothing did happen; my guardian angel was up there with me. When I was finished, the flight engineer gave me a fistful of notes and heartfelt gratitude. How much he gave me, I can’t remember – but I did learn a big lesson about volunteering from that episode!

The General Service Medal (GSM)

For simply being there (well, I suppose I did do my bit, however small that may have been), I was entitled to the General Service Medal. Having been in the theatre of operations for at least 30 days, I could have the clasps “Radfan” and “South Arabia”.

The clasp for “Radfan” came with the medal, when it was issued, but you will have noticed, that the clasp “South Arabia” is brand-spanking new. I only claimed it in 2010 ...and yes, I cleaned the medal, prior to my taking its picture for these recollections!

The clasp for “Radfan” came with the medal, when it was issued, but you will have noticed, that the clasp “South Arabia” is brand-spanking new. I only claimed it in 2010 ...and yes, I cleaned the medal, prior to my taking its picture for these recollections!

The ubiquitous flip-flops

Here’s a line-up of desert boots. Note that the shorts are definitely not an inch and a half above the knee!

The long road to a commission and goodbye Aden

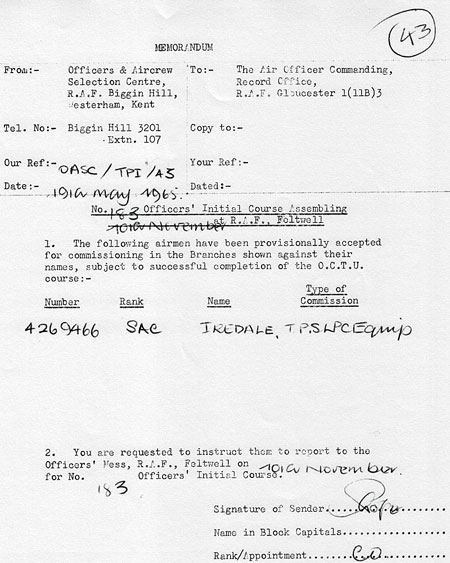

The long road to a commission and goodbye Aden After quite a bit of consideration and encouragement from my friends, I decided to apply for a commission in the Equipment Branch (as it was called then) and submitted my application in December 1964. Just over a month later in early February 1965, I was recommended to appear before a commissioning board at HQ Middle East Command in Steamer Point. Four weeks later on the 10th March, I was notified that I had been selected to attend the Officers and Aircrew Selection Centre (OASC) at RAF Biggin Hill for the selection process beginning on 5th May 1965. I was also allowed to take 20 days leave after finishing the OASC.

I left Aden on the 1st May and did the 12 hour trip to Lyneham on a Britannia. I duly reported to Biggin Hill on the appointed date and underwent the 3 day selection process, which I found quite interesting. After this was over, I then went home on leave to spend with my family at RAF Headley Court, which gave me a chance to see my still very little brothers and sisters again. At the end of my leave, I had to report to RAF Innsworth to wait until I was allocated a flight back. This took another seven or eight days, mainly hanging about, not knowing if you had to up sticks and away at short notice. So I arrived back around the 10th of June and was met off the aircraft by a mate who worked in Station Headquarters. He told me that I had been selected for officer training. This was indeed great news and I was dying to know when this would take place.

I found out soon enough, that I was to report to the Officer Cadet Training Unit (OCTU) to attend No 183 Officers Initial Course at RAF Feltwell on 10th November 1965. The best news was that I was scheduled to depart Aden on 29th September and was under orders not to report early to RAF Feltwell. This meant in effect, that I had 42 days leave – on top of the 20 I had already had in May – so all was well with my little world. I just had to get through the rest of July, August and September and then goodbye Aden, I hope, forever!

I left Aden on the 1st May and did the 12 hour trip to Lyneham on a Britannia. I duly reported to Biggin Hill on the appointed date and underwent the 3 day selection process, which I found quite interesting. After this was over, I then went home on leave to spend with my family at RAF Headley Court, which gave me a chance to see my still very little brothers and sisters again. At the end of my leave, I had to report to RAF Innsworth to wait until I was allocated a flight back. This took another seven or eight days, mainly hanging about, not knowing if you had to up sticks and away at short notice. So I arrived back around the 10th of June and was met off the aircraft by a mate who worked in Station Headquarters. He told me that I had been selected for officer training. This was indeed great news and I was dying to know when this would take place.

I found out soon enough, that I was to report to the Officer Cadet Training Unit (OCTU) to attend No 183 Officers Initial Course at RAF Feltwell on 10th November 1965. The best news was that I was scheduled to depart Aden on 29th September and was under orders not to report early to RAF Feltwell. This meant in effect, that I had 42 days leave – on top of the 20 I had already had in May – so all was well with my little world. I just had to get through the rest of July, August and September and then goodbye Aden, I hope, forever!

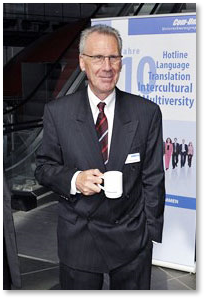

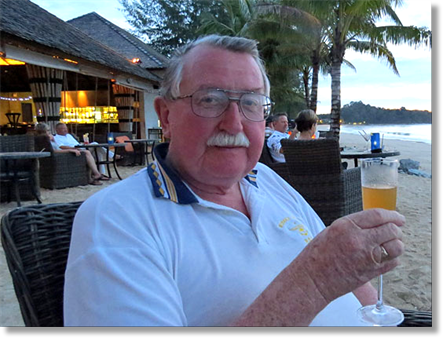

The author - 50 years on

Goodbye Aden!

It was, I suppose, early in 1963 that I found myself clambering aboard a troopship (I think it was the "Nevasa“), as OC RAF en-route for Aden with a party of green young airmen. I use the term advisedly because the Army, always kind to its sister service, had decided to stow them in the pointy bit. Their reasoning became clear as we ploughed through a stormy Bay of Biscay!

I found myself in Aden. Many times in the past I had sailed in and out of the place with its forbidding grey volcanic rock, virtually devoid of greenery. This time I was to stay. Our first view of Aden did not altogether fill us with joy, a first impression which was to prove only too accurate in the years ahead.

The main areas were the port of Steamer Point, Crater, which as its name suggests, was at the core of the extinct volcano and the airfield at Khormaksar some seven miles from Steamer Point. Linked by a causeway was the oil refinery area of Little Aden. Both the Officers’ Mess and Headquarters Middle East Command overlooked Steamer Point.

I booked into the HQ MEC Mess and was duly allocated my cell. As a form of greeting I found myself blasted by a sandstorm which, on later inspection, proved to have found its way even into my drawers, of both varieties!

My working day on the Joint Movements Planning Staff, which had special responsibility for the MAMS Teams, started at seven. This was where we wrote war plans designed to cater for possible eventualities using the forces available in the theatre. There was a simple rule... you write the plan... it happens... you go and do it. This concentrates the mind! We, in this context, were one Wing Commander, one Major, and me. There was no air conditioning and to put it mildly it was hot. The volcanic rock soaked up the heat during the day and pushed it out again at night. The working day ended at one (or thereabouts) whereafter the sensible ones made their way to the Club and bathed both insides and out with suitable liquid.

In due course I was joined by my family and we found ourselves in a hot-box flatlet on 'Murder Mile', aka the Maalla Strait. Our near neighbours were the medicos in their block which was quickly named Bedside Manor. Aden was very inhospitable, even allowing for the various atrocities of the time, and very much a man’s world. Without dwelling on the local situation unduly, mention of the Warrant Officer dragged off a bus and incinerated in front of his family, and the hand grenade thrown onto the veranda of the PMO's house where his daughter was holding a 21st birthday party celebration. We always moved with one eye over the shoulder.

I found myself in Aden. Many times in the past I had sailed in and out of the place with its forbidding grey volcanic rock, virtually devoid of greenery. This time I was to stay. Our first view of Aden did not altogether fill us with joy, a first impression which was to prove only too accurate in the years ahead.

The main areas were the port of Steamer Point, Crater, which as its name suggests, was at the core of the extinct volcano and the airfield at Khormaksar some seven miles from Steamer Point. Linked by a causeway was the oil refinery area of Little Aden. Both the Officers’ Mess and Headquarters Middle East Command overlooked Steamer Point.

I booked into the HQ MEC Mess and was duly allocated my cell. As a form of greeting I found myself blasted by a sandstorm which, on later inspection, proved to have found its way even into my drawers, of both varieties!

My working day on the Joint Movements Planning Staff, which had special responsibility for the MAMS Teams, started at seven. This was where we wrote war plans designed to cater for possible eventualities using the forces available in the theatre. There was a simple rule... you write the plan... it happens... you go and do it. This concentrates the mind! We, in this context, were one Wing Commander, one Major, and me. There was no air conditioning and to put it mildly it was hot. The volcanic rock soaked up the heat during the day and pushed it out again at night. The working day ended at one (or thereabouts) whereafter the sensible ones made their way to the Club and bathed both insides and out with suitable liquid.

In due course I was joined by my family and we found ourselves in a hot-box flatlet on 'Murder Mile', aka the Maalla Strait. Our near neighbours were the medicos in their block which was quickly named Bedside Manor. Aden was very inhospitable, even allowing for the various atrocities of the time, and very much a man’s world. Without dwelling on the local situation unduly, mention of the Warrant Officer dragged off a bus and incinerated in front of his family, and the hand grenade thrown onto the veranda of the PMO's house where his daughter was holding a 21st birthday party celebration. We always moved with one eye over the shoulder.

Despite everything we managed to make our own amusement. I had had some experience in Singapore running the Changi Theatre Club and had been headhunted to stage shows in Aden and this we did in the Khormaksar School.

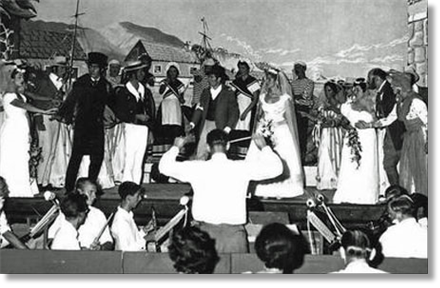

With a company about sixty strong, service, civilian, wives and camp followers we managed to stage three productions in the next three years. All Gilbert and Sullivan, the first was "The Sorcerer" which ran for six nights in November 63.

This was followed in '64 by “Ruddigore" (or “The Witch’s Curse”) and, by courtesy of Bridgit D'Oyly Carte, presented the operetta in its original form using the old F Copy musical scores which she loaned me.

Then, in February 1965, came "The Pirates of Penzance." That's me in the picture at left with the conductor's baton during a dress rehearsal of Pirates. For all these the original costumes were researched, designed and made under the supervision of Maisie Jones, wife of Flt Lt Dave Jones, an Air Mover there.

With a company about sixty strong, service, civilian, wives and camp followers we managed to stage three productions in the next three years. All Gilbert and Sullivan, the first was "The Sorcerer" which ran for six nights in November 63.

This was followed in '64 by “Ruddigore" (or “The Witch’s Curse”) and, by courtesy of Bridgit D'Oyly Carte, presented the operetta in its original form using the old F Copy musical scores which she loaned me.