From: Michael Cocker, Swindon, Wilts

Subject: Hotel Stories

Hi Tony,

In 1985 I was lucky enough to be tasked to support the Commonwealth Conference in Nassau, Bahamas. My team mates were Sgt Taff (Alan) Owen and Cpl (Trevor) Oz Oswald, sadly now both departed. We were tasked with deploying and recovering the close protection team for the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and her husband, Dennis, with a single C130. (As an aside, it was the late, great, Jim Stewart who was the MOpsO at the time, who imparted the good news of this epic adventure.)

Subject: Hotel Stories

Hi Tony,

In 1985 I was lucky enough to be tasked to support the Commonwealth Conference in Nassau, Bahamas. My team mates were Sgt Taff (Alan) Owen and Cpl (Trevor) Oz Oswald, sadly now both departed. We were tasked with deploying and recovering the close protection team for the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and her husband, Dennis, with a single C130. (As an aside, it was the late, great, Jim Stewart who was the MOpsO at the time, who imparted the good news of this epic adventure.)

Having arrived in Nassau, we quickly unloaded the 2 x Transit vans and, duly covered in sweat and grease, headed down to the hotel. This turned out to be the "Nassau Beach Hotel", the one used by James Bond in the film "Goldfinger". It also happened to be the same hotel that the Prime Minister and her husband were staying in. We wandered into the hotel just as Mrs Thatcher was leaving and were quickly grabbed by a member of staff and hidden behind reception, but not before we heard her tell Dennis to leave his drink behind!

All this was great fun, but even moreso when we realised that we had no work to do for at least 2 weeks! However, the British High Commision in St Lucia had other ideas!

All this was great fun, but even moreso when we realised that we had no work to do for at least 2 weeks! However, the British High Commision in St Lucia had other ideas!

They were having a garden party and were in need of some extra plastic chairs - enter UKMAMS and 47 Sqn. We flew down to St Lucia with the required chairs, waited a few days in an all inclusive beach hotel (with absolutely no stories to tell), then flew the chairs back to Nassau and the monotony of another week in a 5-star hotel and casino, surrounded by BA and KLM stewardesses... hell for another few days...

Our departure eventually happened, with an eventful flypast along the beach (a little flight control issue!), past the hotel, heading for Boston. Once in the cruise I made some coffee for Taff and Oz, and our delightful SF passengers (about 8 of them) assumed I was their "Trolly Dolly" for the flight, so they came to me everytime they wanted a drink or food - bloody annoying, but I wasn't about to tell them to sod off!

We had one night in Boston, in an unremarkable hotel, however, while trying to enter a night club a couple of blocks away, the doorman suggested we may not want to come in - we were insistent, and he let us in. While we sat at the bar having a manly drink, I think we all noticed at the same time, several men dancing together very closely, with more than a peck on the cheek going on... We drank up and left, thanking the doorman for his advice.

The rest of the trip was uneventful, but I do wish I'd had a camera with me. Taff Owen and Oz Oswald were two of the finest team mates you could wish for, and I cherish the memories. I do have another tale of a task with Oz, but that will wait for another day. I must be careful not to spoil the book.

All the best

Mick

Our departure eventually happened, with an eventful flypast along the beach (a little flight control issue!), past the hotel, heading for Boston. Once in the cruise I made some coffee for Taff and Oz, and our delightful SF passengers (about 8 of them) assumed I was their "Trolly Dolly" for the flight, so they came to me everytime they wanted a drink or food - bloody annoying, but I wasn't about to tell them to sod off!

We had one night in Boston, in an unremarkable hotel, however, while trying to enter a night club a couple of blocks away, the doorman suggested we may not want to come in - we were insistent, and he let us in. While we sat at the bar having a manly drink, I think we all noticed at the same time, several men dancing together very closely, with more than a peck on the cheek going on... We drank up and left, thanking the doorman for his advice.

The rest of the trip was uneventful, but I do wish I'd had a camera with me. Taff Owen and Oz Oswald were two of the finest team mates you could wish for, and I cherish the memories. I do have another tale of a task with Oz, but that will wait for another day. I must be careful not to spoil the book.

All the best

Mick

From: David Bernard, Bicester, Oxon

Subject: A trilogy of Hotel Experiences

Hello Tony,

I missed the deadline for “hotel experiences” but offer this trilogy of hotel stories:

Subject: A trilogy of Hotel Experiences

Hello Tony,

I missed the deadline for “hotel experiences” but offer this trilogy of hotel stories:

Back in the mid-60s, in the days of Hastings operations and Transport Command, crews visiting RAF Kai Tak were accommodated in a hotel on Nathan Road, Hong Kong called the Shamrock. I remember the skipper, one Flt Lt Johnny Johnson ringing the bell at reception and being confronted by a wizened old dear, all of 4ft 5 inches tall, with the complexion of a dried prune. The skipper announced that we were an RAF crew requiring 6 rooms.

She looked up and in very clear English announced, “I know you all RAF crew, you all have big cock, pee in sink and pay by cheque”! It took several ice cold San Miguel’s to recover from her perceptive comment

In 1972, I was attached to 216 Squadron and had arrived in Chiang Mai as part of a ‘proving flight’ in advance of a royal visit to the far east. I had booked the crew into what looked like a reasonable hotel and we dispersed to our rooms. On arrival in my room I was greeted by a young Thai lass who told me that she was my servant for the stay and would provide anything I wanted! I thanked her and ushered her towards the door. She became very distressed and eventually backed into a large alcove with a bed behind a curtain. Clearly, this girl was part of the room service.

Almost immediately the phone rang and the boss, Basil D'Oliveira, told me to get the whole crew together in the hotel manager’s office to discuss the ‘predicament’ as he called it. Apparently, the young ladies were included with every room and to dismiss them would cause shame on their families and financial hardship. The solution was to hire extra rooms where all these young lasses would reside until we checked out in a couple of days. Room service had taken on an entirely new meaning!

In 1972, I was attached to 216 Squadron and had arrived in Chiang Mai as part of a ‘proving flight’ in advance of a royal visit to the far east. I had booked the crew into what looked like a reasonable hotel and we dispersed to our rooms. On arrival in my room I was greeted by a young Thai lass who told me that she was my servant for the stay and would provide anything I wanted! I thanked her and ushered her towards the door. She became very distressed and eventually backed into a large alcove with a bed behind a curtain. Clearly, this girl was part of the room service.

Almost immediately the phone rang and the boss, Basil D'Oliveira, told me to get the whole crew together in the hotel manager’s office to discuss the ‘predicament’ as he called it. Apparently, the young ladies were included with every room and to dismiss them would cause shame on their families and financial hardship. The solution was to hire extra rooms where all these young lasses would reside until we checked out in a couple of days. Room service had taken on an entirely new meaning!

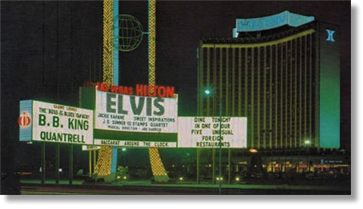

Sometime in the mid-1970s I was asked to join 241 OCU as imprest/admin officer for their annual “States Trainer”. The itinerary included Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada – a short drive from Las Vegas.

For some reason no accommodation had been pre-booked, so after a long walk to base ops I called a number of hotels requesting 12 rooms. The only hotel with rooms available was the Hilton. At reception I asked for rooms to be allocated as close as possible.

For some reason no accommodation had been pre-booked, so after a long walk to base ops I called a number of hotels requesting 12 rooms. The only hotel with rooms available was the Hilton. At reception I asked for rooms to be allocated as close as possible.

Meanwhile, one of the crew, Taff Williams, in jest and in a loud Welsh accent, kept repeating that he wanted “a four poster bed with a mirror-tiled ceiling”. All the rooms were allocated on the 15th floor with Taff being the exception, allocated a room on the 12th floor. When I arrived in my room the phone was ringing; it was Taff. “Get down to my room – there is a problem” he insisted. When I arrived in his room, a bridal suite, there was a massive four-poster bed and a mirror-tiled ceiling with Taff pleading for a room change! Be careful what you wish for.

Best Wishes,

Dave

Best Wishes,

Dave

RAF pilot reveals near miss on the runway at Kabul airport

An RAF pilot missed smashing his aircraft into a bus carrying evacuees at Kabul airport by about 3m (10ft) after the vehicle steered onto the runway as he was taking off.

Wing Commander Kev Latchman revealed military air traffic controllers had been praying for him when they saw his C-17 transport aircraft hurtling towards a line of three vehicles that had taken a wrong turn while trying to reach another evacuation flight. "At this point, we were doing about 95 knots and they were about a thousand feet ahead of us," he said, speaking from RAF Brize Norton airbase in Oxfordshire. We realised that we wouldn't have been able to reject [abort] the take-off, because if I tried to reject then I would have basically... taken out the bus and that doesn't really bear thinking about."

Wing Commander Kev Latchman revealed military air traffic controllers had been praying for him when they saw his C-17 transport aircraft hurtling towards a line of three vehicles that had taken a wrong turn while trying to reach another evacuation flight. "At this point, we were doing about 95 knots and they were about a thousand feet ahead of us," he said, speaking from RAF Brize Norton airbase in Oxfordshire. We realised that we wouldn't have been able to reject [abort] the take-off, because if I tried to reject then I would have basically... taken out the bus and that doesn't really bear thinking about."

He decided he had to continue with the take-off but then realised that there was not enough distance between his aircraft and the bus to be able to reach the required speed to get airborne - what is known as rotate speed. "So I said, I think we're going to need to rotate early. And the other pilot agreed. We started to rotate the aircraft about 20 knots earlier than rotate speed. "We got airborne and we just missed the bus by probably about 10, 15ft." He said a member of his crew had also put the distance at about 10ft. Making things even more of a challenge, the airman was having to fly without any runway lights because the power at the airport had failed.

The incident happened on 26 August at a time of acute tensions following a suicide bomb attack hours earlier that had ripped through crowds of people who had been waiting for evacuation flights.

Wing Commander Latchman, who commands 99 Squadron, said he had apparently been "quite calm" while dealing with the potential bus disaster "because you've got no choice". The close call hit home following a conversation with air traffic controllers. "We didn't think you were going to make it. We were praying for you," he recalled them saying.

The near miss is just one of a number of stories to emerge from Operation Pitting, the UK's two-week evacuation mission from Kabul airport after the Western-backed Afghan government collapsed in a Taliban takeover last month. The RAF flew more than 15,000 Afghans, British nationals and others to safety in the biggest evacuation effort since the Second World War.

Aircrew described what it was like to look after plane-loads of desperate Afghans, many who had never flown before and were traumatised after spending days in the heat and crowds outside the airport, waiting to be called forward for a flight. "The conditions were stark, you know, when you look down the back, you've got anxious faces," said Wing Commander Latchman. "You had some people who didn't think they were going to leave Afghanistan. So when they got on board the airplane... the relief led to, you know, some spontaneous reactions. We had one lady who was spontaneously vomiting continuously all over the airplane because she'd lost her husband the day before and she didn't know what was going to happen."

There was also the hazard to the aircrew of operating out of an airport in a country now under Taliban control. One pilot described how he had to abort an attempt to land in Kabul on 16 August - the day after the city fell to the Taliban - because crowds of people had surged onto the airfield and swarmed over aircraft on the ground, including a US military plane. "We could see the airfield was completely overrun," said Flight Lieutenant Neil Franklin, of 70 Squadron, who flies the A400M Atlas transport aircraft.

"There were people on the taxiways, people on the southern apron, and the civilian airliners were covered in people... it was just utter chaos.

As well as the danger posed by crowds, there was the danger posed by terrorist attacks and - on the day Kabul fell - being caught up in the closing stages of the Taliban surge to power.

Squadron Leader Mark Parker, of 70 Squadron, had just dropped off some British troops at Kabul airport on 15 August when the airfield itself was targeted by gunfire and mortars. He said it was hard to know what was going on. "The US Marines in the tower called incoming, base under attack," the officer said. "We had some rounds impacting the ground around our aircraft… And I recall an American helicopter pilot calling mortars inbound and he flew off to have a look at the mortar tube."

The pilot said he was not able to get his A400 plane off the ground straight away as there was too much traffic so they had to wait for about 30 seconds to a minute. "We took off with some kind of firefight going on at the south side of the airport," he said, adding that his aircraft thankfully was not hit.

World News | Sky News

Wing Commander Latchman, who commands 99 Squadron, said he had apparently been "quite calm" while dealing with the potential bus disaster "because you've got no choice". The close call hit home following a conversation with air traffic controllers. "We didn't think you were going to make it. We were praying for you," he recalled them saying.

The near miss is just one of a number of stories to emerge from Operation Pitting, the UK's two-week evacuation mission from Kabul airport after the Western-backed Afghan government collapsed in a Taliban takeover last month. The RAF flew more than 15,000 Afghans, British nationals and others to safety in the biggest evacuation effort since the Second World War.

Aircrew described what it was like to look after plane-loads of desperate Afghans, many who had never flown before and were traumatised after spending days in the heat and crowds outside the airport, waiting to be called forward for a flight. "The conditions were stark, you know, when you look down the back, you've got anxious faces," said Wing Commander Latchman. "You had some people who didn't think they were going to leave Afghanistan. So when they got on board the airplane... the relief led to, you know, some spontaneous reactions. We had one lady who was spontaneously vomiting continuously all over the airplane because she'd lost her husband the day before and she didn't know what was going to happen."

There was also the hazard to the aircrew of operating out of an airport in a country now under Taliban control. One pilot described how he had to abort an attempt to land in Kabul on 16 August - the day after the city fell to the Taliban - because crowds of people had surged onto the airfield and swarmed over aircraft on the ground, including a US military plane. "We could see the airfield was completely overrun," said Flight Lieutenant Neil Franklin, of 70 Squadron, who flies the A400M Atlas transport aircraft.

"There were people on the taxiways, people on the southern apron, and the civilian airliners were covered in people... it was just utter chaos.

As well as the danger posed by crowds, there was the danger posed by terrorist attacks and - on the day Kabul fell - being caught up in the closing stages of the Taliban surge to power.

Squadron Leader Mark Parker, of 70 Squadron, had just dropped off some British troops at Kabul airport on 15 August when the airfield itself was targeted by gunfire and mortars. He said it was hard to know what was going on. "The US Marines in the tower called incoming, base under attack," the officer said. "We had some rounds impacting the ground around our aircraft… And I recall an American helicopter pilot calling mortars inbound and he flew off to have a look at the mortar tube."

The pilot said he was not able to get his A400 plane off the ground straight away as there was too much traffic so they had to wait for about 30 seconds to a minute. "We took off with some kind of firefight going on at the south side of the airport," he said, adding that his aircraft thankfully was not hit.

World News | Sky News

Story behind fist-bump between Afghan boy and airman

A Norfolk airman has said that his duty as a father helped him in the largest air evacuation carried out by the RAF in over 70 years.

Belton father-of-two, Sgt Chris Hall has shared his thoughts on the moment he was photographed fist-bumping an Afghan boy boarding a Royal Air Force (RAF) plane during the evacuation of Kabul in late August.

The picture was featured on the front pages of several British national newspapers and has been regarded as one of the defining images of the Afghan evacuation.

Sgt Hall, 39, who is based in Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, with the UK Mobile Air Movements Squadron (UKMAMS), said: "There were families getting on the aircraft and some of the children hadn't seen a plane before. "Many kids were crying at the bottom of the ramp. One boy was crying and refusing to get aboard. So I crouched down and said 'come on, mate' and gave him a fist-bump. Then about eight kids behind the boy came up and they all wanted a fist-bump as well."

Belton father-of-two, Sgt Chris Hall has shared his thoughts on the moment he was photographed fist-bumping an Afghan boy boarding a Royal Air Force (RAF) plane during the evacuation of Kabul in late August.

The picture was featured on the front pages of several British national newspapers and has been regarded as one of the defining images of the Afghan evacuation.

Sgt Hall, 39, who is based in Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, with the UK Mobile Air Movements Squadron (UKMAMS), said: "There were families getting on the aircraft and some of the children hadn't seen a plane before. "Many kids were crying at the bottom of the ramp. One boy was crying and refusing to get aboard. So I crouched down and said 'come on, mate' and gave him a fist-bump. Then about eight kids behind the boy came up and they all wanted a fist-bump as well."

Great Yarmouth Mercury

From: Doug Stewart, Stouffville, ON

Subject: Afghanistan

Hello Tony,

Well done all RAF personnel. You were there when called. At the age of 94, I still look back with much pride at my service during 1945/1948 [Aden and Salalah]. God Bless each and every one of you!

Doug Stewart

Subject: Afghanistan

Hello Tony,

Well done all RAF personnel. You were there when called. At the age of 94, I still look back with much pride at my service during 1945/1948 [Aden and Salalah]. God Bless each and every one of you!

Doug Stewart

I left the Royal Air Force in August 2011 after nine years’ service, including two tours of Afghanistan and one in Iraq.

I left the RAF to take up a role as a civilian contractor based in the Afghan capital, Kabul. Following a merry-go-round of decisions on my future in the forces, with MOD cuts doing the rounds. My old boss in the RAF, being my new boss in Kabul, had a significant impact on my decision and in what seemed like an instant, I had departed the gates of RAF Northolt and was on final approach to Kabul International Airport, via a few days of paperwork and training in Dubai.

The company I worked for had a presence in each of the airfields within Afghanistan from Kabul to Kandahar, to Camp Bastion, Mazar-e-Sharif, Jalalabad, Herat, you name it and we were there. Kabul though, was the only base the company had in which staff were accommodated “off-site” as in away from airport operations and the safe haven of NATO troops. We were to reside in a secure compound known as Green Village around a mile and a half away from Kabul Airport.

It was only on the day of the flight from Dubai, alongside a fellow new starter, did I appreciate the fact I’d be landing on a civilian airliner (Fly Dubai) on the civilian side of the airport. I had been under the impression I’d be landing and handled on the military side of the airfield and thus a little safer!

As the mountains of Kabul loomed towards the descending aircraft, Mihai, my new colleague, gave me a glance and raised his eyebrows, as if to say, “Here we go then!”

I left the RAF to take up a role as a civilian contractor based in the Afghan capital, Kabul. Following a merry-go-round of decisions on my future in the forces, with MOD cuts doing the rounds. My old boss in the RAF, being my new boss in Kabul, had a significant impact on my decision and in what seemed like an instant, I had departed the gates of RAF Northolt and was on final approach to Kabul International Airport, via a few days of paperwork and training in Dubai.

The company I worked for had a presence in each of the airfields within Afghanistan from Kabul to Kandahar, to Camp Bastion, Mazar-e-Sharif, Jalalabad, Herat, you name it and we were there. Kabul though, was the only base the company had in which staff were accommodated “off-site” as in away from airport operations and the safe haven of NATO troops. We were to reside in a secure compound known as Green Village around a mile and a half away from Kabul Airport.

It was only on the day of the flight from Dubai, alongside a fellow new starter, did I appreciate the fact I’d be landing on a civilian airliner (Fly Dubai) on the civilian side of the airport. I had been under the impression I’d be landing and handled on the military side of the airfield and thus a little safer!

As the mountains of Kabul loomed towards the descending aircraft, Mihai, my new colleague, gave me a glance and raised his eyebrows, as if to say, “Here we go then!”

From: Mal Robinson, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear

Subject: Memories of Afghanistan

Mal Robinson reflects on his time as a civilian contractor in Kabul and how the recent horrific scenes in the Afghan capital, following the resurgence of the Taliban in country, brought back memories of an 8-month stay 10 years ago.

Subject: Memories of Afghanistan

Mal Robinson reflects on his time as a civilian contractor in Kabul and how the recent horrific scenes in the Afghan capital, following the resurgence of the Taliban in country, brought back memories of an 8-month stay 10 years ago.

Kabul Crisis Evokes Memories for Mal

The airport had not been touched since the 1950’s, or so it seemed. Only one of the baggage belts was working and a long queue ensued for foreign nationals entering the country. There was a lot of noise and a lot of commotion and it all seemed to be a state of organized chaos. After an hour or so, we finally made it through customs, imports and whatever documentation check was available. All the while, it was playing on my mind what scene would meet me outside the terminal.

We were told in no circumstances were we to use the flurry of yellow cabs waiting outside. I was told to wait for our HR manager to meet us outside the terminal but after ten minutes or so there was no sign. What we thought was a local Afghan woman with a black veil over her head approached us. It was Ingrid, our HR manager who thought she’d have a little fun with us on our first sojourn into Kabul.

The whole airport looked to be a scene of chaos, but if the arrival was edgy at times, the first and subsequent departures were ten times more nerve wracking.

To leave the country via the airport there seemed to be a labyrinth of security checks and scanners, designed to identify any would-be terrorist at the earliest opportunity and negate a suicide attack inside or near the terminal. There had been many security instances already which had killed locals in and around the facility.

The route into Kabul airport and its surrounds was not a place then to hang around and the name of the game was to get into the airside of departures as soon as possible. This was easier said than done. Following the endless stop and searches, on entering departures a melee greeted you once inside. There were several flights leaving that day and although check-in desks were open, there seemed to be no particular queue for any individual flight.

I was asked several times to pay locals in order to help facilitate my journey through the madness to check-in a little easier and by the time the tenth person asked me for dollars to check me in, I accepted.

It was then a case of waiting to get through customs and on some occasions, it would take several hours, one time even seeing a group of us storm to the front and ask to be let through as our flight (for which we were many hours early for) was about to depart!

We were told in no circumstances were we to use the flurry of yellow cabs waiting outside. I was told to wait for our HR manager to meet us outside the terminal but after ten minutes or so there was no sign. What we thought was a local Afghan woman with a black veil over her head approached us. It was Ingrid, our HR manager who thought she’d have a little fun with us on our first sojourn into Kabul.

The whole airport looked to be a scene of chaos, but if the arrival was edgy at times, the first and subsequent departures were ten times more nerve wracking.

To leave the country via the airport there seemed to be a labyrinth of security checks and scanners, designed to identify any would-be terrorist at the earliest opportunity and negate a suicide attack inside or near the terminal. There had been many security instances already which had killed locals in and around the facility.

The route into Kabul airport and its surrounds was not a place then to hang around and the name of the game was to get into the airside of departures as soon as possible. This was easier said than done. Following the endless stop and searches, on entering departures a melee greeted you once inside. There were several flights leaving that day and although check-in desks were open, there seemed to be no particular queue for any individual flight.

I was asked several times to pay locals in order to help facilitate my journey through the madness to check-in a little easier and by the time the tenth person asked me for dollars to check me in, I accepted.

It was then a case of waiting to get through customs and on some occasions, it would take several hours, one time even seeing a group of us storm to the front and ask to be let through as our flight (for which we were many hours early for) was about to depart!

Fast forward to August 2021 and I can’t begin to imagine the chaos and hysteria surrounding Kabul International Airport now. I watched in disbelief at how quickly the Taliban regained control of the country and watched in horror the scenes of civilians on the tarmac at the airport trying to board aircraft in vain and clinging to the side of outgoing military aircraft. I felt empty watching it all unfold. It wasn’t just the fact that I’d been in Afghanistan with the RAF and then as a contractor, it was the fact this event, which the whole world was watching live, happened on my old working patch.

The terminal, the North Gate (where so many are crammed at the time of writing, trying in vain to flee the country), the roads around the airport that I knew so well and now the scene of carnage, as UK soldiers and their counterparts with a huge ongoing situation none of us in our time had encountered before.

My heart goes out to them all doing such a fantastic job in the most trying of circumstances. If what I had experienced at Kabul Airport was a sense of normality, who knows what pandemonium ensues as the deadline to evacuate Westerners and entitled people approaches.

The scenes on TV caused anxiety through a number of emotions and trains of thought, including the inevitable questions, “What was the point of it all? What was the point of us being there in the first place?” It isn’t until you start to unravel those thoughts and analyse facts, figures and actions do you begin to realise we all played a part in re-opening schools, educating girls, allowing at least two generations of Afghans to taste some kind of normal and allow them to lead better lives. I only hope and pray that the country does not return to the state allied forces found it back in 2001.

I end on the memory of one of my former drivers in Kabul, who now, thankfully, has fled to Germany to live (yet his family remain in serious danger in Kabul) and his recollections of wild dogs roaming the streets feeding on mounds of human remains, thanks to brutal killings from the Taliban. The wild animals became so accustomed to eating dead bodies they developed a taste for human beings, and as a result people would need to run for fear of attack not only from the Taliban but wild dogs too. For the sake of humanity, let us hope the darkness of those days does not cloud Afghanistan once again.

Mal Robinson

(Former RAF Mover and now Editor of Pathfinder International Magazine)

The terminal, the North Gate (where so many are crammed at the time of writing, trying in vain to flee the country), the roads around the airport that I knew so well and now the scene of carnage, as UK soldiers and their counterparts with a huge ongoing situation none of us in our time had encountered before.

My heart goes out to them all doing such a fantastic job in the most trying of circumstances. If what I had experienced at Kabul Airport was a sense of normality, who knows what pandemonium ensues as the deadline to evacuate Westerners and entitled people approaches.

The scenes on TV caused anxiety through a number of emotions and trains of thought, including the inevitable questions, “What was the point of it all? What was the point of us being there in the first place?” It isn’t until you start to unravel those thoughts and analyse facts, figures and actions do you begin to realise we all played a part in re-opening schools, educating girls, allowing at least two generations of Afghans to taste some kind of normal and allow them to lead better lives. I only hope and pray that the country does not return to the state allied forces found it back in 2001.

I end on the memory of one of my former drivers in Kabul, who now, thankfully, has fled to Germany to live (yet his family remain in serious danger in Kabul) and his recollections of wild dogs roaming the streets feeding on mounds of human remains, thanks to brutal killings from the Taliban. The wild animals became so accustomed to eating dead bodies they developed a taste for human beings, and as a result people would need to run for fear of attack not only from the Taliban but wild dogs too. For the sake of humanity, let us hope the darkness of those days does not cloud Afghanistan once again.

Mal Robinson

(Former RAF Mover and now Editor of Pathfinder International Magazine)

Escape from Kabul; NZDF crew back in NZ after 'chaotic' evacuation

New Zealand Army soldiers used code words and messenger apps to help navigate "chaotic and dangerous" scenes to evacuate Kiwis in Afghanistan. However, having to leave some New Zealand visa holders behind weighed heavily on the minds of the Defence Force, Commander Joint Forces New Zealand Rear Admiral Jim Gilmour said. There were horrific scenes in the last days of evacuations as people clung to the bottom of planes as they took off from Kabul's main airport last month, fearful of being left behind and instead dropping to their deaths.

The Taliban took over the war-torn country last week and now the world remains on tenterhooks as to how it would be run, if women would be equal, or if it would resort back to its 1990s style.

Gilmour said the evacuation of Kiwis had been a huge multi-agency, international effort. "Our thoughts are with those New Zealand visa holders still in Afghanistan who wanted to evacuate but have been unable to," he said. While acknowledging those facing uncertainty in Afghanistan, he said he was proud of Defence Force personnel who "worked tirelessly to bring many others to safety here in New Zealand".

As part of the NZDF's Operation Kōkako, New Zealand Army soldiers were on the ground at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul and used code words and instructions sent on messenger apps to help evacuees reach the soldiers, where they could be taken to safety within the airport perimeter.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130 Hercules deployed on the mission completed three flights to Kabul, and had two more flights scheduled before being forced to pull out due to an imminent security threat that was realised just hours later with an attack claimed by Isis-K that left 170 civilians and 13 United States military dead, with many more injured.

Other members of the NZDF contingent were at a base in the United Arab Emirates, supporting evacuees prior to their onward travel to New Zealand.

Rear Admiral Gilmour said all those involved had worked through an "incredibly fluid and complex situation" to bring people to safety. He praised their efforts in evacuating New Zealand nationals, their families and other visa holders from Kabul following the takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban. "There are real stories of bravery, initiative and professionalism among our personnel and equally of bravery and incredible resilience among evacuees."

Although NZDF deployed about 80 personnel on the operation, it was estimated that around 600 NZDF staff were involved in a range of activities from planning, logistics and co-ordination through to mobilisation in order to achieve the mission. Hundreds of staff from other Government agencies and thousands from international partners were involved in the humanitarian effort.

NZDF personnel involved with the Afghanistan evacuations returned to New Zealand and completed two weeks of managed isolation.

nzherald.co.nz

The Taliban took over the war-torn country last week and now the world remains on tenterhooks as to how it would be run, if women would be equal, or if it would resort back to its 1990s style.

Gilmour said the evacuation of Kiwis had been a huge multi-agency, international effort. "Our thoughts are with those New Zealand visa holders still in Afghanistan who wanted to evacuate but have been unable to," he said. While acknowledging those facing uncertainty in Afghanistan, he said he was proud of Defence Force personnel who "worked tirelessly to bring many others to safety here in New Zealand".

As part of the NZDF's Operation Kōkako, New Zealand Army soldiers were on the ground at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul and used code words and instructions sent on messenger apps to help evacuees reach the soldiers, where they could be taken to safety within the airport perimeter.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130 Hercules deployed on the mission completed three flights to Kabul, and had two more flights scheduled before being forced to pull out due to an imminent security threat that was realised just hours later with an attack claimed by Isis-K that left 170 civilians and 13 United States military dead, with many more injured.

Other members of the NZDF contingent were at a base in the United Arab Emirates, supporting evacuees prior to their onward travel to New Zealand.

Rear Admiral Gilmour said all those involved had worked through an "incredibly fluid and complex situation" to bring people to safety. He praised their efforts in evacuating New Zealand nationals, their families and other visa holders from Kabul following the takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban. "There are real stories of bravery, initiative and professionalism among our personnel and equally of bravery and incredible resilience among evacuees."

Although NZDF deployed about 80 personnel on the operation, it was estimated that around 600 NZDF staff were involved in a range of activities from planning, logistics and co-ordination through to mobilisation in order to achieve the mission. Hundreds of staff from other Government agencies and thousands from international partners were involved in the humanitarian effort.

NZDF personnel involved with the Afghanistan evacuations returned to New Zealand and completed two weeks of managed isolation.

nzherald.co.nz

Photo of British airman holding Afghan baby

as exhausted mother sleeps goes viral

as exhausted mother sleeps goes viral

A British airman is being hailed as a hero after photos of him cradling an Afghan mother's two-week-old baby on a rescue flight out of Kabul went viral online. Sergeant Andy Livingstone, 31, an air loadmaster on the RAF A400M held the baby in his hands for almost two hours after he noticed that her barely conscious mother dropped her on the floor.

Livingstone was responsible for loading refugees and equipment onto the last rescue flight which took off from Kabul hours after the ISIS-K suicide bombing outside the Kabul airport.

The airman said that he first noticed the baby's mother was having trouble shortly after they took off.

"We got everyone on and this family caught my eye, a mum and dad, three sisters and a brother. One of the sisters was in the early stages of shock or exhaustion, so without any medics there we just cracked on giving her food and I was dealing with dad, ensuring he was able to give food and water to his family," Livingstone said.

The mother did not understand what the airman had said in English, however, she could comprehend that he would take care of the baby. She looked at the sergeant as if to say "is it okay? Can I go to sleep now? Is my baby going to be okay with you?" he recalled.

Livingstone was responsible for loading refugees and equipment onto the last rescue flight which took off from Kabul hours after the ISIS-K suicide bombing outside the Kabul airport.

The airman said that he first noticed the baby's mother was having trouble shortly after they took off.

"We got everyone on and this family caught my eye, a mum and dad, three sisters and a brother. One of the sisters was in the early stages of shock or exhaustion, so without any medics there we just cracked on giving her food and I was dealing with dad, ensuring he was able to give food and water to his family," Livingstone said.

The mother did not understand what the airman had said in English, however, she could comprehend that he would take care of the baby. She looked at the sergeant as if to say "is it okay? Can I go to sleep now? Is my baby going to be okay with you?" he recalled.

Sky News

He put a pair of ear deafeners on the little girl so that she could sleep peacefully during the two-hour journey to Dubai.

"I just did what anyone else would have done. I've got two little girls myself and you just want to help," he said.

"I just did what anyone else would have done. I've got two little girls myself and you just want to help," he said.

Afghanistan: ADF tells of ‘harrowing’ Kabul evacuation

The Australian Defence Force has opened up on its “chaotic” rescue mission in Kabul where it helped evacuate 4100 people in 32 flights.

Joint Operations Command tweeted an overview of what was involved to get thousands of evacuees out of Kabul airport, which was the subject of a terrorist attack that killed 13 US service members and at least 90 Afghans: “The military mission was led by Commander Joint Task Force 633, Air Commodore David Paddison, with subordinate air, land, and support elements. Around 250 extra troops and four aircraft were deployed to augment those already in the Middle East,” the ADF said. “The first Australian evacuation flight occurred on 17 August. As the team established themselves at the airport, each subsequent flight would carry increasing numbers of evacuees. One C-17A carried more than 350 passengers, floor loaded.”

The ADF said that troops had to wear night vision googles to navigate the busy airspace and mountainous terrain, using eight air-to-air refuelling planes. “In less than three days, ADF engineers and contractors turned a bare patch of sand into a camp to cater for the needs of 450 evacuees, which then expanded to accommodate more than 3000,” Joint Operations Command tweeted. “Many evacuees were women and children. Some only days old, and some were born shortly following their evacuation flight.”

The ADF went on to say that the stories of those being evacuated “were harrowing, but hopeful. “For our soldiers at the airport gates, it was urgent, chaotic, and dangerous work. But their sense of purpose was absolute,” the ADF said. “Throughout the operation, the 1st Joint Movements Unit co-ordinated all flights to Afghanistan and back to Australian capital cities. They negotiated additional contracted aircraft, and managed relations with airports. Commercial airlines assisted as well.”

All up, the ADF evacuated more than 4100 people in 32 flights from Kabul. More than 3500 now call Australia home.

Defence Minister Peter Dutton claimed some Afghans who had worked with Australian troops had switched their allegiance to the Taliban and that it was proving difficult for Australian officials to prove their identity. He confirmed he rejected some people because of fear they may carry out a terrorist attack in Australia. “It’s the reality we’re dealing with,” he said, without revealing specific numbers. “Ascertaining someone’s identity is difficult in that part of the world.” There were an estimated 130 Australian citizens in Kabul when the city fell to the Taliban last week.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison praised the Australian military’s work in Kabul. “The people are doing this job on the ground, they are real heroes, compassionate heroes,” Mr Morrison said. “Dealing with people in the most distressing and dangerous of situations. Our ADF, our air force flying people in and out, those from three brigades there on the ground doing the job providing security and supporting people getting onto these planes, our Home Affairs officials, our Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade officials, they’re going through what is an extraordinarily intense time – and they’re getting people out.”

news.com.au

Joint Operations Command tweeted an overview of what was involved to get thousands of evacuees out of Kabul airport, which was the subject of a terrorist attack that killed 13 US service members and at least 90 Afghans: “The military mission was led by Commander Joint Task Force 633, Air Commodore David Paddison, with subordinate air, land, and support elements. Around 250 extra troops and four aircraft were deployed to augment those already in the Middle East,” the ADF said. “The first Australian evacuation flight occurred on 17 August. As the team established themselves at the airport, each subsequent flight would carry increasing numbers of evacuees. One C-17A carried more than 350 passengers, floor loaded.”

The ADF said that troops had to wear night vision googles to navigate the busy airspace and mountainous terrain, using eight air-to-air refuelling planes. “In less than three days, ADF engineers and contractors turned a bare patch of sand into a camp to cater for the needs of 450 evacuees, which then expanded to accommodate more than 3000,” Joint Operations Command tweeted. “Many evacuees were women and children. Some only days old, and some were born shortly following their evacuation flight.”

The ADF went on to say that the stories of those being evacuated “were harrowing, but hopeful. “For our soldiers at the airport gates, it was urgent, chaotic, and dangerous work. But their sense of purpose was absolute,” the ADF said. “Throughout the operation, the 1st Joint Movements Unit co-ordinated all flights to Afghanistan and back to Australian capital cities. They negotiated additional contracted aircraft, and managed relations with airports. Commercial airlines assisted as well.”

All up, the ADF evacuated more than 4100 people in 32 flights from Kabul. More than 3500 now call Australia home.

Defence Minister Peter Dutton claimed some Afghans who had worked with Australian troops had switched their allegiance to the Taliban and that it was proving difficult for Australian officials to prove their identity. He confirmed he rejected some people because of fear they may carry out a terrorist attack in Australia. “It’s the reality we’re dealing with,” he said, without revealing specific numbers. “Ascertaining someone’s identity is difficult in that part of the world.” There were an estimated 130 Australian citizens in Kabul when the city fell to the Taliban last week.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison praised the Australian military’s work in Kabul. “The people are doing this job on the ground, they are real heroes, compassionate heroes,” Mr Morrison said. “Dealing with people in the most distressing and dangerous of situations. Our ADF, our air force flying people in and out, those from three brigades there on the ground doing the job providing security and supporting people getting onto these planes, our Home Affairs officials, our Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade officials, they’re going through what is an extraordinarily intense time – and they’re getting people out.”

news.com.au

RCAF Operates Large Evacuation Flight from Kabul

On Aug. 24, an RCAF CC-177 Globemaster III carried 506 people from Kabul – Canada’s largest evacuation flight to date

The CC-177 was one of two RCAF strategic lift aircraft participating in a multinational air bridge to evacuate citizens and Afghan nationals and families who have worked with coalition forces over the past 20 years, as the Taliban solidifies its grip on the country and the capital city. The aircraft and crews are from 429 Transport Squadron at 8 Wing Trenton, Ontario.

In a background briefing on Aug. 23, government officials said Canadian aircraft had conducted 13 flights and airlifted 1,700 Canadians and eligible Afghans from Kabul since Operation Aegis began.

According to CBC News, four of those flights took place since Aug. 19. About 188 people were on board the first flight, 106 on the second, 121 on the third, and 436 on the fourth. The flight on Aug. 24 would appear to be the largest to date. According to Global News, more than 200 of the 506 passengers were children.

In the briefing to media, government officials also confirmed that members of Canadian Special Operations Forces were on the ground outside Hamid Karzai International Airport, Kabul, to get Canadian citizens and eligible Afghan nationals through the security gates.

“For operational security reasons, for obvious reasons, I cannot divulge exactly what our troops are doing. One thing I can say: they have all of the flexibility to make all of the appropriate decisions so they can take action,” Sajjan said on Aug. 22, according to CBC.

Canada is among 13 countries participating in an air bridge agreement under which the allies are all transporting their citizens, foreign nationals, and Afghan nationals. U.S. President Joe Biden had suggested the airlift could continue beyond an initial Aug. 31 deadline, but a Taliban spokesperson told Sky News on Aug. 24 the new self-proclaimed Afghan government would not agree to an extension. There would be “consequences” if the “occupation” of the airport continues, he added.

skiesmag.com

In a background briefing on Aug. 23, government officials said Canadian aircraft had conducted 13 flights and airlifted 1,700 Canadians and eligible Afghans from Kabul since Operation Aegis began.

According to CBC News, four of those flights took place since Aug. 19. About 188 people were on board the first flight, 106 on the second, 121 on the third, and 436 on the fourth. The flight on Aug. 24 would appear to be the largest to date. According to Global News, more than 200 of the 506 passengers were children.

In the briefing to media, government officials also confirmed that members of Canadian Special Operations Forces were on the ground outside Hamid Karzai International Airport, Kabul, to get Canadian citizens and eligible Afghan nationals through the security gates.

“For operational security reasons, for obvious reasons, I cannot divulge exactly what our troops are doing. One thing I can say: they have all of the flexibility to make all of the appropriate decisions so they can take action,” Sajjan said on Aug. 22, according to CBC.

Canada is among 13 countries participating in an air bridge agreement under which the allies are all transporting their citizens, foreign nationals, and Afghan nationals. U.S. President Joe Biden had suggested the airlift could continue beyond an initial Aug. 31 deadline, but a Taliban spokesperson told Sky News on Aug. 24 the new self-proclaimed Afghan government would not agree to an extension. There would be “consequences” if the “occupation” of the airport continues, he added.

skiesmag.com

We need to talk about RAF Air Transport

Evacuees from Afghanistan disembark an RAF C130

Twenty years ago (23 August 2001) UK Army soldiers arrived in Macedonia. They went there as part of a NATO mission to collect weapons from ethnic Albanian rebels as part of a ceasefire agreement. Like the air evacuation currently taking place in Afghanistan, the Army response was spearheaded by the Parachute Regiment. But, like during the last week, central to operations was the RAF Air Mobility Force.

A few days ahead of the Macedonia deployment, Dr Sophy Antrobus, then in charge of ASCOT operations overseeing RAF air transport around the world, was called to a Contingency Action Group meeting at RAF High Wycombe. Standard practice for a short notice task, the aim was to get all teams across the RAF from administration to force protection around the table to consider and to plan.

After a relatively short meeting, the senior officer in charge started to wrap up, summarising the operation as an Army event, so little more needed discussing in an RAF context. Sophy put her hand up and asked, a little sarcastically, ‘well, how are they going to get there?’. Nobody around the table had remembered that no operation like this happens without air transport. To their credit, they immediately apologised for the oversight and set to work discussing the transport challenges.

Two months later 9/11 happened and, again, air transport was absolutely key to the UK’s contribution to operations in Afghanistan. Kabul airport was austere (a wreck of an airport really), and the RAF’s aircraft were not equipped with the defensive equipment needed to safely land there. During their first sorties to Afghanistan some transport crews sat on cargo chains to protect themselves from ground fire; the RAF’s fast-jet senior leadership had considered providing body armour unnecessary.

Twenty years on, we are seeing the same centrality of air transport to military capability. 27% of sorties flown by the coalition in Afghanistan from 2014-2020 were air mobility flights. A figure only surpassed by intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) sorties at 41%. Strike attack was just 18% and in 2020 the majority of sorties were ISR 39% and air transport 38%. And now we see the Non-Combatant Evacuation Operation (NEO) to rescue UK nationals and eligible Afghans from country after the apparently unforeseen capitulation of the Afghan Forces to the Taliban, following the United States’ precipitous withdrawal.

The operation has seen the RAF Air Mobility Force rise to the challenge of evacuating 1,000 people a day from Kabul airport. A steady stream of C-17s, A400M, Voyager, and C-130J aircraft take people from mortal danger and despair to safety and hope. This is not air mobility as an enabler for other force elements, as it is so often narrowly and incorrectly viewed by many in the RAF, never mind wider Defence. This is air mobility as air power: ‘influencing the behaviour of actors and course of events’ as it is defined in UK doctrine.

It therefore seems incredible that the MoD intends to cut the RAF Air Mobility Force by nearly 30% over the next two years. Even before the Kabul Airlift this looked strategically incoherent with the ‘Global Britain’ ambition set out in the Integrated Review. After the Kabul Airlift it looks reckless.

Critics may point out that the UK is unlikely to repeat its Afghanistan misadventure in the foreseeable future. And they are right. However, rising instability across the globe, coupled with large UK diasporas in some of the regions most at risk, make it hard to conclude this will be the UK’s last large NEO. Indeed, the next one could be much bigger.

We must hope the MoD will now rethink its cut to air mobility. Otherwise commanders in the future may find themselves repeating Sophy’s question: ‘how are they going to get there?’

wavellroom.com

A few days ahead of the Macedonia deployment, Dr Sophy Antrobus, then in charge of ASCOT operations overseeing RAF air transport around the world, was called to a Contingency Action Group meeting at RAF High Wycombe. Standard practice for a short notice task, the aim was to get all teams across the RAF from administration to force protection around the table to consider and to plan.

After a relatively short meeting, the senior officer in charge started to wrap up, summarising the operation as an Army event, so little more needed discussing in an RAF context. Sophy put her hand up and asked, a little sarcastically, ‘well, how are they going to get there?’. Nobody around the table had remembered that no operation like this happens without air transport. To their credit, they immediately apologised for the oversight and set to work discussing the transport challenges.

Two months later 9/11 happened and, again, air transport was absolutely key to the UK’s contribution to operations in Afghanistan. Kabul airport was austere (a wreck of an airport really), and the RAF’s aircraft were not equipped with the defensive equipment needed to safely land there. During their first sorties to Afghanistan some transport crews sat on cargo chains to protect themselves from ground fire; the RAF’s fast-jet senior leadership had considered providing body armour unnecessary.

Twenty years on, we are seeing the same centrality of air transport to military capability. 27% of sorties flown by the coalition in Afghanistan from 2014-2020 were air mobility flights. A figure only surpassed by intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) sorties at 41%. Strike attack was just 18% and in 2020 the majority of sorties were ISR 39% and air transport 38%. And now we see the Non-Combatant Evacuation Operation (NEO) to rescue UK nationals and eligible Afghans from country after the apparently unforeseen capitulation of the Afghan Forces to the Taliban, following the United States’ precipitous withdrawal.

The operation has seen the RAF Air Mobility Force rise to the challenge of evacuating 1,000 people a day from Kabul airport. A steady stream of C-17s, A400M, Voyager, and C-130J aircraft take people from mortal danger and despair to safety and hope. This is not air mobility as an enabler for other force elements, as it is so often narrowly and incorrectly viewed by many in the RAF, never mind wider Defence. This is air mobility as air power: ‘influencing the behaviour of actors and course of events’ as it is defined in UK doctrine.

It therefore seems incredible that the MoD intends to cut the RAF Air Mobility Force by nearly 30% over the next two years. Even before the Kabul Airlift this looked strategically incoherent with the ‘Global Britain’ ambition set out in the Integrated Review. After the Kabul Airlift it looks reckless.

Critics may point out that the UK is unlikely to repeat its Afghanistan misadventure in the foreseeable future. And they are right. However, rising instability across the globe, coupled with large UK diasporas in some of the regions most at risk, make it hard to conclude this will be the UK’s last large NEO. Indeed, the next one could be much bigger.

We must hope the MoD will now rethink its cut to air mobility. Otherwise commanders in the future may find themselves repeating Sophy’s question: ‘how are they going to get there?’

wavellroom.com

From: Chris Goss, Marlow, Bucks

Subject: Memories of Afghanistan

Tony

I wish I had kept a diary and taken a camera as one month after 9/11 just after we had moved MQs having been posted from RAF Odiham to HQSTC, I got a knock on the door at 0730 hrs. It was Russ Huxtable who told me not to put on my uniform, get myself to work, then off to London to various embassies ending in "stan" and then to get to the Turkish Air Force HQ at Ankara for 1030 hrs on Friday.

Subject: Memories of Afghanistan

Tony

I wish I had kept a diary and taken a camera as one month after 9/11 just after we had moved MQs having been posted from RAF Odiham to HQSTC, I got a knock on the door at 0730 hrs. It was Russ Huxtable who told me not to put on my uniform, get myself to work, then off to London to various embassies ending in "stan" and then to get to the Turkish Air Force HQ at Ankara for 1030 hrs on Friday.

There were just two of us; the other chap was an armaments squadron leader. We were part of a multi-national team reporting to CENTCOM to try and find suitable airbases around Afghanistan.

I packed for 6 months, but after visiting most counties, we were back in 3 weeks, only to then go out again with the German army to identify the bases for themselves. Quite exciting - poor wife didn't have a clue where I was until I phoned and gave her the hint that I could see the Chinese border.

Too many stories to relate during the month and a half I was out there, apart from Russ and I devised a code and I would phone him first thing in the morning UK time to tell him what I had seen - most air bases were totally unsuitable and very little basic life support to such an extent that the conscripts at one base had a farm so they could feed themselves!

Regards

Chris

I packed for 6 months, but after visiting most counties, we were back in 3 weeks, only to then go out again with the German army to identify the bases for themselves. Quite exciting - poor wife didn't have a clue where I was until I phoned and gave her the hint that I could see the Chinese border.

Too many stories to relate during the month and a half I was out there, apart from Russ and I devised a code and I would phone him first thing in the morning UK time to tell him what I had seen - most air bases were totally unsuitable and very little basic life support to such an extent that the conscripts at one base had a farm so they could feed themselves!

Regards

Chris

Interviews with RAF Brize Norton Personnel on Operation PITTING

On the Lighter Side

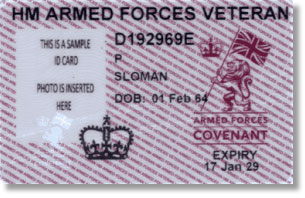

Update on UK Veterans' ID Cards

Behind the scenes there is a lot of work going on at present across Government, the Charity sector and other providers to improve services for veterans, all linked to the Armed Forces Covenant.

The delay in offering an ID card more widely to veterans is partly so that the Department can complete work to consider how best a future card, or veterans identity approach, can support these services for veterans in the future. Unfortunately, this work is going to take more time to resolve and we don't currently have a date from which we can say cards will be available.

The delay in offering an ID card more widely to veterans is partly so that the Department can complete work to consider how best a future card, or veterans identity approach, can support these services for veterans in the future. Unfortunately, this work is going to take more time to resolve and we don't currently have a date from which we can say cards will be available.

We will post updates on https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/veterans-uk when more is known.

UK air force still not re-examining plans to retire C-130

WASHINGTON — The arduous airlift demands of the Afghanistan evacuation mission haven’t changed the U.K. Royal Air Force’s plans to retire its C-130s by 2023, its top officer said on August 27. “This is the first large-scale operation that we’ve done with our A400s, and it’s demonstrated that this is an aircraft with real potential and enormous capacity,” said RAF Air Chief Marshal Mike Wigston in an interview with Defense News. “It flies much higher and much faster and carries a greater payload than the C-130. So as every month goes by, my confidence in that decision increases.”

The RAF ultimately transported more than 15,000 people out of Kabul from Aug. 14 to Aug. 28, according to the U.K. Ministry of Defence.

The RAF used about 15 aircraft during the evacuation mission, with half staged forward — transporting passengers from Kabul to other cities in the Middle East — and the other planes conducting flights from those cities to the United Kingdom, Wigston said. Over the two-week period, aircraft spotters frequently documented British C-17s, A400s and C-130s moving in and out of the airspace at Hamid Karzai International Airport.

In March, the defence ministry announced as part of a command review it would retire the RAF’s remaining 14 C-130Js by 2023. “Twenty-two A400Ms, alongside the C17s, will provide a more capable and flexible transport fleet,” U.K. Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said then.

Despite the C-130s offering additional airlift capacity, Wigston said there’s no need for the RAF to revisit its current retirement plans. “It will be with a heavy heart that we retire the C-130 in two years’ time because it’s been an absolute workhorse, but I have absolute confidence in the A400 and what that aircraft is able to do going forward,” he said.

So far, Airbus has delivered 20 A400M Atlas aircraft to the RAF.

defensenews.com

The RAF ultimately transported more than 15,000 people out of Kabul from Aug. 14 to Aug. 28, according to the U.K. Ministry of Defence.

The RAF used about 15 aircraft during the evacuation mission, with half staged forward — transporting passengers from Kabul to other cities in the Middle East — and the other planes conducting flights from those cities to the United Kingdom, Wigston said. Over the two-week period, aircraft spotters frequently documented British C-17s, A400s and C-130s moving in and out of the airspace at Hamid Karzai International Airport.

In March, the defence ministry announced as part of a command review it would retire the RAF’s remaining 14 C-130Js by 2023. “Twenty-two A400Ms, alongside the C17s, will provide a more capable and flexible transport fleet,” U.K. Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said then.

Despite the C-130s offering additional airlift capacity, Wigston said there’s no need for the RAF to revisit its current retirement plans. “It will be with a heavy heart that we retire the C-130 in two years’ time because it’s been an absolute workhorse, but I have absolute confidence in the A400 and what that aircraft is able to do going forward,” he said.

So far, Airbus has delivered 20 A400M Atlas aircraft to the RAF.

defensenews.com

From: John Bell, Birmingham

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

One of the regular scheduled flights to arrive at RAF Kai Tak was the Gurkha trooping flight from Nepal. As was the norm, the passengers were called forward to clear customs in order of seniority. This I did until I read the name Lt Colpant. By then all the captains, majors and colonels had been called and cleared customs. When I called his name a very angry Nepalese officer came over to me and accused me of being prejudiced. His English was not very good and I did not understand what he was saying. He cleared his baggage and left.

Regards,

John

John

The following morning the SAMO, Squadron Leader Gil O’Toole, and the Commander RAF Kai Tak (CRAFHK) Air Commodore Frow, were summoned by the GOC In response to a serious complaint. On their return I was summoned to the SAMOs office and told that the Nepalese Ambassador to the UK had been on the Gurkha flight and had not been shown the necessary respect. It turned out that LT COLPANT was in fact LT COL PANT. The passenger manifest had shown his rank and name incorrectly and there was no mention of VIP status. After I produced a copy of the manifest and explained how this near diplomatic incident had come about no more was said.

From: Stephen Bird, Chester

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Hi Tony,

Nothing on Afghanistan as I had left before all of that really started. But have been immensely proud of those who have followed us in this trade group, who I imagine served in virtually intolerable conditions whilst doing the evacuations in recent weeks - thanks for your efforts!

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Hi Tony,

Nothing on Afghanistan as I had left before all of that really started. But have been immensely proud of those who have followed us in this trade group, who I imagine served in virtually intolerable conditions whilst doing the evacuations in recent weeks - thanks for your efforts!

Now onto a passenger brief. Whilst serving in Gutersloh in the mid 80's, I worked in every role in GUT including pax, under John Guy, a fellow Northamptonion.

The one passenger brief which sticks in my mind was a normal trooper flight which occurred several times a week with a 30 minute turn around. It was a standard flight back to Luton but we had several VIP's on the flight or let's say those designated VIP's, it was always debatable who was a real VIP!

The one passenger brief which sticks in my mind was a normal trooper flight which occurred several times a week with a 30 minute turn around. It was a standard flight back to Luton but we had several VIP's on the flight or let's say those designated VIP's, it was always debatable who was a real VIP!

But back to the story. On this particular flight one of the VIP's was the comedian Jim Davidson, he was returning to the UK after a number of shows in RAFG/BOAR. We advised him that he could use the VIP Lounge, but Jim being Jim and a bit worse for wear after his previous night's antics, insisted on sitting amongst "his" troops.

At this point I started the standard passenger departure brief, and was only 30 seconds in when Jim took the microphone out of my hand and started an impromptu stand-up routine. I cannot remember it all in detail, but I am sure his fictitious mate "Chalky" would have been mentioned at some point. Anyway, after five mins or so, life returned to normal and all the passengers were boarded. I never got any feedback, but I should imagine the standard 60 plus minute flight back to Luton was far from normal with Jim on board!

At this point I started the standard passenger departure brief, and was only 30 seconds in when Jim took the microphone out of my hand and started an impromptu stand-up routine. I cannot remember it all in detail, but I am sure his fictitious mate "Chalky" would have been mentioned at some point. Anyway, after five mins or so, life returned to normal and all the passengers were boarded. I never got any feedback, but I should imagine the standard 60 plus minute flight back to Luton was far from normal with Jim on board!

The one thing which did come across to me in that brief meeting with Jim, was that he was a really nice bloke. He may now not sit comfortably in this PC world we live in but he did have a lot of time for HM Forces.

Regards,

Stephen

Regards,

Stephen

Royal Air Force trials self-driving cars

The Royal Air Force has been trialling the use of self-driving cars as it explores ways to free up personnel from mundane tasks on military bases.

Editor: <le sigh... >

From: Andrew Spinks, Falmouth, Cornwall

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Hi Tony,

It was July 1981 and the G7 meeting that year took place in Ottawa. Margaret Thatcher was the PM and I was the RAF Unit Cdr at CFB Ottawa (with the small unit comprising myself, Colin Allen, Clive Bishop and Mal Palfrey). Maggie always used to fly by VC10 and it was no different on this occasion. But, of relevance to this tale, the US President would also be flying in.

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Hi Tony,

It was July 1981 and the G7 meeting that year took place in Ottawa. Margaret Thatcher was the PM and I was the RAF Unit Cdr at CFB Ottawa (with the small unit comprising myself, Colin Allen, Clive Bishop and Mal Palfrey). Maggie always used to fly by VC10 and it was no different on this occasion. But, of relevance to this tale, the US President would also be flying in.

For any RAF arrival into CFB Ottawa, which was the same airfield as Ottawa International (YOW), we had to collect the Canada Customs officers from the civil side of the Airport and drive them to the military side, where we were collated with 3 AMU. It was a long drive on public roads but only a short drive airside, along a taxiway, for which we had a VHF radio fitted in the pick-up. A quick call to ATC to clear us on to the taxiway and a good lookout was all that was required; it was all fairly straightforward and our trusty Ford pick-up with rotating yellow lights on the roof used the callsign “Air Force One”.

Anyway, while Colin and crew prepared the steps and other ground equipment, off I went to pick up the Canada Customs officer for the VC10’s arrival.

Me: “Ottawa Ground, Air Force One requesting permission to enter Alpha".

It was perhaps unfortunate that, at the time, the real Air Force One Boeing 747 was also on the ground! Hence, Ottawa Tower: “Royal Air Force mobile, we had better give you another callsign otherwise things could get interesting… Use RAF Mobile now… RAF Mobile, clear to enter Alpha, please expedite”.

Anyway, while Colin and crew prepared the steps and other ground equipment, off I went to pick up the Canada Customs officer for the VC10’s arrival.

Me: “Ottawa Ground, Air Force One requesting permission to enter Alpha".

It was perhaps unfortunate that, at the time, the real Air Force One Boeing 747 was also on the ground! Hence, Ottawa Tower: “Royal Air Force mobile, we had better give you another callsign otherwise things could get interesting… Use RAF Mobile now… RAF Mobile, clear to enter Alpha, please expedite”.

But that was not really a faux pas. What was more of one was when the PM departed after the G7. I was at the foot of the steps - as one had to be - and I was usually pretty good about chatting to the VIP (and non-VIP) pax when they were boarding. But for some strange reason, perhaps fearful of the PM’s reputation, I just stood bolt upright, saluted very smartly and looked straight ahead. She even thanked me and, with the benefit of hindsight, I guess she would have appreciated some response and, who knows, a little chat. But, stunned into silence as I was, I guess she decided it was not worthwhile pursuing the matter and climbed the steps.

I will always remember that day; it was not so much that I was rude in any way to our PM, it was just that it was so out of character for me not to be at ease with a passenger and not to at least wish her a pleasant flight. I always wondered what it would have been like to have a chat to her - or maybe she would just have climbed the steps anyway! A faux pas? Probably!

I will always remember that day; it was not so much that I was rude in any way to our PM, it was just that it was so out of character for me not to be at ease with a passenger and not to at least wish her a pleasant flight. I always wondered what it would have been like to have a chat to her - or maybe she would just have climbed the steps anyway! A faux pas? Probably!

Kind regards,

Andy

Andy

From: David Powell, Princes Risborough, Bucks

Subject: Subject Fox’s Parts

Dear Tony,

My biggest faux pas does have a movements twist but occurred many years, actually decades, since I had last signed off a trim sheet. Some of you pre-decimal coin vintage colleagues may remember a tall black haired smooth team leader from Abingdon days, one Brian Shorter. He then moved on from ramp tramping and spent much of his service career in the world of Mov Ops both at Upavon and then MoD. In the early 1990s, Brian was in MoD Main Building. Although I think I was still down the road in Neville House in the RAF Log Ops shop. In those days it was all strictly civilian rig.

Subject: Subject Fox’s Parts

Dear Tony,

My biggest faux pas does have a movements twist but occurred many years, actually decades, since I had last signed off a trim sheet. Some of you pre-decimal coin vintage colleagues may remember a tall black haired smooth team leader from Abingdon days, one Brian Shorter. He then moved on from ramp tramping and spent much of his service career in the world of Mov Ops both at Upavon and then MoD. In the early 1990s, Brian was in MoD Main Building. Although I think I was still down the road in Neville House in the RAF Log Ops shop. In those days it was all strictly civilian rig.

One morning I was trundling around one of the higher floors in Main Building when I spotted the unmistakable rear profile of Brian several yards away heading off down the corridor I had just entered. Obviously I hailed (bellowed?) with a typical mover’s colloquial greeting. I will leave you to imagine which one.

Brian stopped. Brian turned, to my horror revealing the quite well known and now seriously puzzled Commander RN (as he was then) Tim Laurence, the then to be or just was Mr Princess Anne! As a professional coward, I took evasive action with a swift diving turn to Port into the nearest open office door which thankfully was Mov Ops or was it Exercise Plans? At least friendly territory where I could claim bureaucratic asylum.

Happy Days.

Brian stopped. Brian turned, to my horror revealing the quite well known and now seriously puzzled Commander RN (as he was then) Tim Laurence, the then to be or just was Mr Princess Anne! As a professional coward, I took evasive action with a swift diving turn to Port into the nearest open office door which thankfully was Mov Ops or was it Exercise Plans? At least friendly territory where I could claim bureaucratic asylum.

Happy Days.

David Powell,

F Team UKMAMS, Abingdon

F Team UKMAMS, Abingdon

From: Jim Mckintosh, Glasgow, North Lanarkshire

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Hi Tony,

In 1961, as a young airman just 5 months out of training, I was stationed at Joint Service Continental Booking Centre, London (JSCBC). The offices were located at 5 Great Scotland Yard, Whitehall, which was the Central London Recruiting Depot for the Army and also the home of the Garrison Sergeant Major (GSM), London District. The GSM was responsible for organising all ceremonials in London including Trooping of the Colour and State Funerals and was an important Army figure.

Subject: Noteworthy Faux Pas

Hi Tony,

In 1961, as a young airman just 5 months out of training, I was stationed at Joint Service Continental Booking Centre, London (JSCBC). The offices were located at 5 Great Scotland Yard, Whitehall, which was the Central London Recruiting Depot for the Army and also the home of the Garrison Sergeant Major (GSM), London District. The GSM was responsible for organising all ceremonials in London including Trooping of the Colour and State Funerals and was an important Army figure.

Our offices were located off the side of a large indoor courtyard which had a small NAAFI kiosk in the middle. The GSM and his men were located in the basement which was accessed via a stairway which was outside our office windows.

On 1st May “Shirt Sleeve Order” came into force for all London district personnel. For the Army this meant rolling up their shirt sleeves with an open necked shirt, whilst in the RAF at that time we wore shirts with detachable collars held in place by a collar stud, which meant we still had to wear a tie.

On 1st May “Shirt Sleeve Order” came into force for all London district personnel. For the Army this meant rolling up their shirt sleeves with an open necked shirt, whilst in the RAF at that time we wore shirts with detachable collars held in place by a collar stud, which meant we still had to wear a tie.

At about 1000hrs, I left our office for our NAAFI break with 2 Army colleagues, my sleeves neatly rolled up and wearing my tie. As we crossed the courtyard, a loud voice bellowed out,"You laddie, come here!"

This was the GSM standing at the top of the steps, resplendent in his No1 dress red tunic with gold braided rank badges (he must have been on his way out to some function). I stopped, shakingly, in front of him and he shouted out, ”What is the dress of the day laddie?”

My reply was “Shirt sleeve order, Sir.”

"Well" he said, “you are improperly dressed, get that tie off and open your shirt collar.”

"But sir...” I said.”

”Don't but me, get on with it!”

This was the GSM standing at the top of the steps, resplendent in his No1 dress red tunic with gold braided rank badges (he must have been on his way out to some function). I stopped, shakingly, in front of him and he shouted out, ”What is the dress of the day laddie?”

My reply was “Shirt sleeve order, Sir.”

"Well" he said, “you are improperly dressed, get that tie off and open your shirt collar.”

"But sir...” I said.”

”Don't but me, get on with it!”