For the third time in 78 years, Sarajevo has been the focus of world attention. June 1914 saw Hapsburg Archduke Franz Ferdinand assassinated in Sarajevo; the event which triggered the crisis leading up to the First World War. February 1984 saw Sarajevo host the Winter Olympic Games and in June 1992, war torn and distraught after three months of bombardment by Serbian, Moslem Slav and Croatian forces, Sarajevo became the subject of a United Nations co-ordinated effort to airlift in humanitarian aid for its desperate in habitants.

In response to the UN appeal for airlift, one C130 Mk1 supported by one UKMAMS team, TCW (Tactical Communications Wing) and ATSy (Air transport Security) was put on immediate standby waiting for the RAF involvement to begin.

The green light finally came 72 hours later on July 2nd when, having been bade farewell by Armed forces minister, Mr Archie Hamilton MP, we departed Lyneham with our payload of press, compo rations and a MAMS Landrover; Operation Cheshire had begun.

As with all other flights in the relief effort, the aircraft first flew to a UN staging area at Zagreb airport in Croatia, where a UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) representative inspected our cargo. Although our cargo was desperately needed in Sarajevo, urgent medical supplies and Croatian ration packs were already on hand at Zagreb when we arrived and these afforded an even higher priority than ours. Because we were the first nation to provide airlift from Zagreb the responsibility for moving this urgent consignment fell to us and, in order to make room for it, 12,000 lbs of British compo rations had to be offloaded – a tiring job on a flat floor aircraft! Eventually with the aircraft reloaded, refuelled and prepared for the following morning’s mercy flight to Sarajevo, we locked up and departed for the hotel. The detachment hotel turned out to be two 12 x 12 tents located in the corner of a dirty, mosquito infested hangar shared with several pigeons, four twin engine light aircraft and a stray dog named “Rabies”. The Mobile RAFLO was more fortunate, his room was a cupboard. The operating crew fared even better they had a boiler room . Nevertheless the accommodation was dry and, for the short term, proved adequate until we were able to find something more permanent.

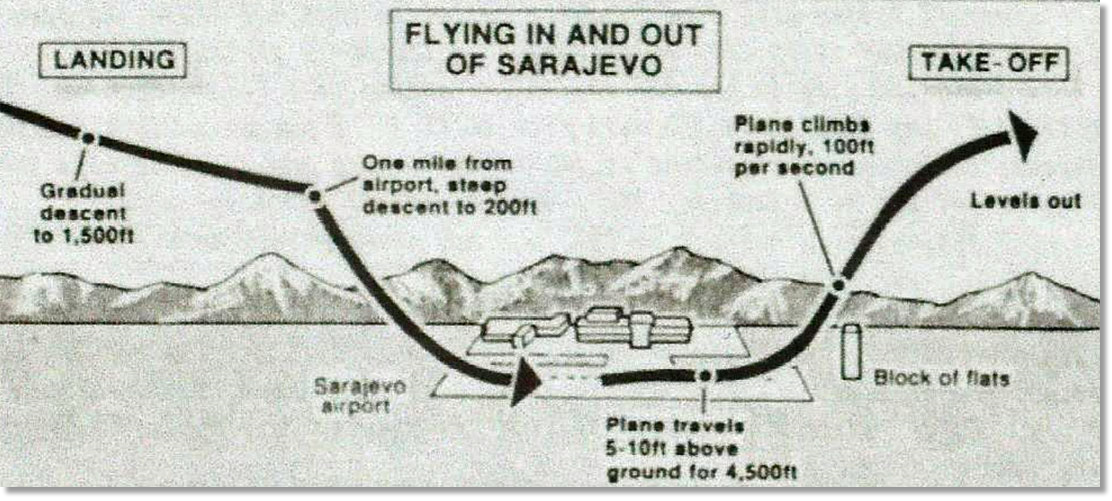

XV196 left Zagreb for Sarajevo for the first time on July 3rd at 0445 hrs GMT. Unsure of the welcome we would receive, as a precautionary measure all crew members were armed, wore flak jackets and carried UN blue berets. Exposure to ground fire was considered a significant risk and in order to avoid Serbian SAM sites our route took us South along the Adriatic coastline to Split and then across the mountains to Sarajevo Airport which nestles in a bowl of mountains 1700 feet above sea level; the flying time was one hour ten minutes. Our approach into the airport was high and steep because even though the warring factions had agreed to allow mercy flights to operate, mortar activity and fire from rogue snipers was commonplace.

In response to the UN appeal for airlift, one C130 Mk1 supported by one UKMAMS team, TCW (Tactical Communications Wing) and ATSy (Air transport Security) was put on immediate standby waiting for the RAF involvement to begin.

The green light finally came 72 hours later on July 2nd when, having been bade farewell by Armed forces minister, Mr Archie Hamilton MP, we departed Lyneham with our payload of press, compo rations and a MAMS Landrover; Operation Cheshire had begun.

As with all other flights in the relief effort, the aircraft first flew to a UN staging area at Zagreb airport in Croatia, where a UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) representative inspected our cargo. Although our cargo was desperately needed in Sarajevo, urgent medical supplies and Croatian ration packs were already on hand at Zagreb when we arrived and these afforded an even higher priority than ours. Because we were the first nation to provide airlift from Zagreb the responsibility for moving this urgent consignment fell to us and, in order to make room for it, 12,000 lbs of British compo rations had to be offloaded – a tiring job on a flat floor aircraft! Eventually with the aircraft reloaded, refuelled and prepared for the following morning’s mercy flight to Sarajevo, we locked up and departed for the hotel. The detachment hotel turned out to be two 12 x 12 tents located in the corner of a dirty, mosquito infested hangar shared with several pigeons, four twin engine light aircraft and a stray dog named “Rabies”. The Mobile RAFLO was more fortunate, his room was a cupboard. The operating crew fared even better they had a boiler room . Nevertheless the accommodation was dry and, for the short term, proved adequate until we were able to find something more permanent.

XV196 left Zagreb for Sarajevo for the first time on July 3rd at 0445 hrs GMT. Unsure of the welcome we would receive, as a precautionary measure all crew members were armed, wore flak jackets and carried UN blue berets. Exposure to ground fire was considered a significant risk and in order to avoid Serbian SAM sites our route took us South along the Adriatic coastline to Split and then across the mountains to Sarajevo Airport which nestles in a bowl of mountains 1700 feet above sea level; the flying time was one hour ten minutes. Our approach into the airport was high and steep because even though the warring factions had agreed to allow mercy flights to operate, mortar activity and fire from rogue snipers was commonplace.

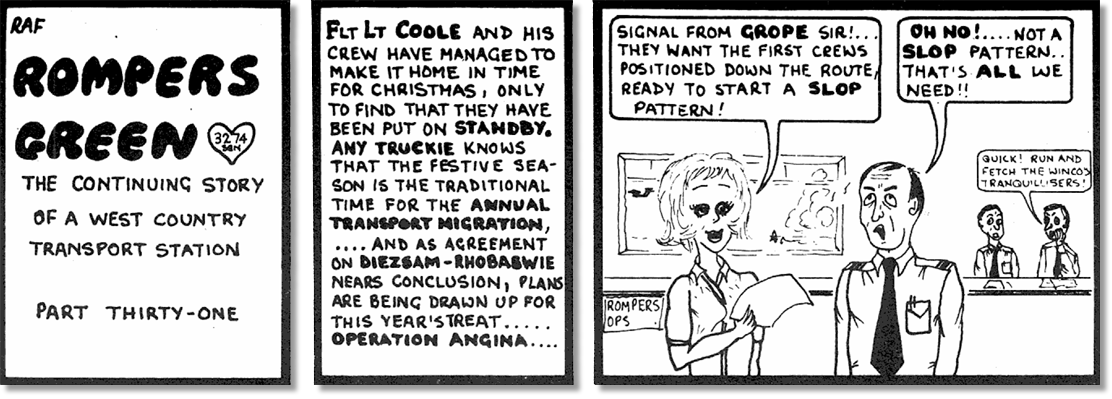

Operation Cheshire – Yugotours with a Difference

by Flt Lt Mike Cumberland, UKMAMS

With ramp and cargo doors open we taxied to our parking slot. Immediately on chox the first truck was marshalled to the rear of the Hercules and we began offloading, our objective to offload and get airborne as quickly as possible. During the turn round small arms and heavy machine gun fire was clearly audible coming mainly from the hotly contested Dobrinja area adjacent to the terminal. Behind us the terminal buildings had been peppered with bullet holes, the majority of windows were shattered and some buildings were showing signs of structural damage.

Following a brief chat with BBC’s Martin Bell we departed for Zagreb to reload and return. Three sorties were completed on July 3rd in which a total of 80,000 lbs of medicine, compo rations and UNHCR emergency parcels which contained corned beef, mackerel, vegetable oil, washing powder and soap were moved.

Over the next three days, eight sorties were completed, each sortie a flat floor load of boxes the size of 10 man ration packs; by the end of the third day, one Hercules and one MAMS team assisted by the crew had moved 250,000 lbs of humanitarian aid. Aid convoys arriving at Zagreb were increasing in frequency and fortunately on July 5th a much needed set of roller and side guidance was flown in from Lyneham. XV196 was re-rolled to 108 inch side guidance and immediately loaded with four pallets of American “Meals Ready to Eat” (MRE) weighing 38,400 lbs. As a result of palletisation, load times were reduced to 15 minutes and offloads at Sarajevo to less than eight minutes as we moved pallet after pallet of MRE’s, sugar, yeast, flour, feta cheese, baby food and family parcels, all built on the UKMAMS production line.

As time progressed more nations became involved and the airlift gathered momentum. With British, German, Canadian and Norwegian movements teams preparing the loads and airlift provided by the Air Forces of Canada, Denmark, Italy, USA, Germany, CIS, Holland, Turkey, France, Greece, Sweden, Norway, Kuwait and ourselves, the UN effort was of true International magnitude. By July 10th a total of 20 sorties were being flown daily into Sarajevo whose 380,000 inhabitants were estimated to need 190 tons of food a day.

At the time of my departure on July 18th the RAF detachment had completed 39 sorties and moved a total of 1,350,000 lbs of humanitarian aid. By the time these words are read, twice as many sorties will have been flown and over 2,000,000 lbs of aid will have been airlifted by the RAF into the beleaguered city. The International airlift is currently Sarajevo’s only lifeline and seems certain to continue until a ground corridor is opened. Although tentative arrangements are underway it seems unlikely this will occur in the near future and until this happens, Operation Cheshire will continue.

In 1993 the RAF detachment relocated to Ancona in Italy and continued daily sorties to Sarajevo until July 1996. The main reason for the relocation from Zagreb was hostility from many locals, acts of sabotage and the risk of assault especially to the French Forces!

When Operation Cheshire ended, the RAF had flown just short of 2,000 sorties and delivered 27,000 tons of humanitarian aid.

Following a brief chat with BBC’s Martin Bell we departed for Zagreb to reload and return. Three sorties were completed on July 3rd in which a total of 80,000 lbs of medicine, compo rations and UNHCR emergency parcels which contained corned beef, mackerel, vegetable oil, washing powder and soap were moved.

Over the next three days, eight sorties were completed, each sortie a flat floor load of boxes the size of 10 man ration packs; by the end of the third day, one Hercules and one MAMS team assisted by the crew had moved 250,000 lbs of humanitarian aid. Aid convoys arriving at Zagreb were increasing in frequency and fortunately on July 5th a much needed set of roller and side guidance was flown in from Lyneham. XV196 was re-rolled to 108 inch side guidance and immediately loaded with four pallets of American “Meals Ready to Eat” (MRE) weighing 38,400 lbs. As a result of palletisation, load times were reduced to 15 minutes and offloads at Sarajevo to less than eight minutes as we moved pallet after pallet of MRE’s, sugar, yeast, flour, feta cheese, baby food and family parcels, all built on the UKMAMS production line.

As time progressed more nations became involved and the airlift gathered momentum. With British, German, Canadian and Norwegian movements teams preparing the loads and airlift provided by the Air Forces of Canada, Denmark, Italy, USA, Germany, CIS, Holland, Turkey, France, Greece, Sweden, Norway, Kuwait and ourselves, the UN effort was of true International magnitude. By July 10th a total of 20 sorties were being flown daily into Sarajevo whose 380,000 inhabitants were estimated to need 190 tons of food a day.

At the time of my departure on July 18th the RAF detachment had completed 39 sorties and moved a total of 1,350,000 lbs of humanitarian aid. By the time these words are read, twice as many sorties will have been flown and over 2,000,000 lbs of aid will have been airlifted by the RAF into the beleaguered city. The International airlift is currently Sarajevo’s only lifeline and seems certain to continue until a ground corridor is opened. Although tentative arrangements are underway it seems unlikely this will occur in the near future and until this happens, Operation Cheshire will continue.

In 1993 the RAF detachment relocated to Ancona in Italy and continued daily sorties to Sarajevo until July 1996. The main reason for the relocation from Zagreb was hostility from many locals, acts of sabotage and the risk of assault especially to the French Forces!

When Operation Cheshire ended, the RAF had flown just short of 2,000 sorties and delivered 27,000 tons of humanitarian aid.

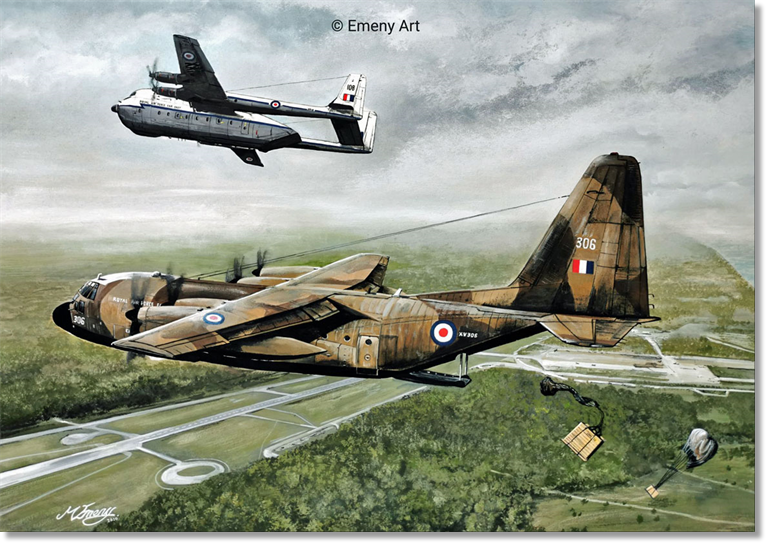

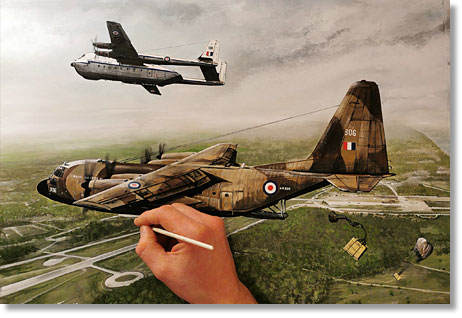

XV196 left Zagreb for Sarajevo for the first time on July 3rd, 1992

Khe San (Space Shuttle) approach into Sarajevo

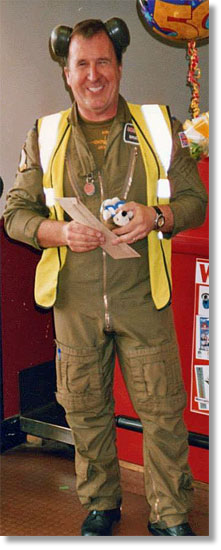

Where's your helmet?

A truly international effort

From: Stephen Tomlinson, Tenerife, QLD

Subject: UKMAMS OBA OBB #093020

G'day Tony,

Good to see you back up-and-running! Just a quick comment for Kepler Aerospace if they get some of the VC-10's back in the air? Please give them a "wicked" paint job, they are a stylishly beautiful aircraft design and deserve it. Further, consider re-christening them with their original RAF Victoria Cross holders' names. Fingers-crossed to see them flying again.

Cheers!

Steve

Subject: UKMAMS OBA OBB #093020

G'day Tony,

Good to see you back up-and-running! Just a quick comment for Kepler Aerospace if they get some of the VC-10's back in the air? Please give them a "wicked" paint job, they are a stylishly beautiful aircraft design and deserve it. Further, consider re-christening them with their original RAF Victoria Cross holders' names. Fingers-crossed to see them flying again.

Cheers!

Steve

From: Tony Street, Buffalo, NY

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #093020

Tony,

Regarding the RCAF's new CC295 Kingfisher aircraft.

Back in the day, when I worked for Metric Systems in Ft. Walton Beach FL, myself and five others were sent to Madrid, Spain, where we were contracted by CASA (now part of Airbus).

Our job was to certify the CC295 for all methods of aerial delivery, including LAPES. A fun month.

Regards

Tony

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #093020

Tony,

Regarding the RCAF's new CC295 Kingfisher aircraft.

Back in the day, when I worked for Metric Systems in Ft. Walton Beach FL, myself and five others were sent to Madrid, Spain, where we were contracted by CASA (now part of Airbus).

Our job was to certify the CC295 for all methods of aerial delivery, including LAPES. A fun month.

Regards

Tony

Timorese students repatriated home on RNZAF flight

A group of students has today (7th October) been repatriated to Timor-Leste after they were stranded in New Zealand by the COVID-19 pandemic. About 30 students were among passengers on a Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130H Hercules flight to Dili. The New Zealand Defence Force has been working with the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Government of Timor-Leste to get the students home. They had been studying at universities and training institutions in New Zealand but have been unable to return home due to the unavailability of commercial passenger flights.

Two staff from non-government organisations Blue Ventures and HANDS Programme were also on the flight. In addition, the flight carried medical supplies including personal protective equipment.

The passengers will undergo 14 days’ managed isolation on arrival in Dili to meet Timor-Leste government requirements.

Air Component Commander Air Commodore Tim Walshe says the RNZAF had carried out a number of repatriation flights to support Pacific neighbours seeking help in getting their citizens home. This included eight flights in June returning more than 1000 Vanuatu nationals, including Recognised Seasonal Employer workers, who had been unable to return home due to the cancellation of commercial flights.

nzdf.co.nz

Two staff from non-government organisations Blue Ventures and HANDS Programme were also on the flight. In addition, the flight carried medical supplies including personal protective equipment.

The passengers will undergo 14 days’ managed isolation on arrival in Dili to meet Timor-Leste government requirements.

Air Component Commander Air Commodore Tim Walshe says the RNZAF had carried out a number of repatriation flights to support Pacific neighbours seeking help in getting their citizens home. This included eight flights in June returning more than 1000 Vanuatu nationals, including Recognised Seasonal Employer workers, who had been unable to return home due to the cancellation of commercial flights.

nzdf.co.nz

From: Tim James, Boston, Lincs

Escape from Iran

Preamble - I was born in 1961, and in 1965 my dad died in a road accident. Shortly afterwards my younger brother was born. In 1968 my mum remarried and I gained a stepfather along with an older stepbrother and stepsister. I’ll just refer to him as my dad for ease. My dad was in the army, so we moved to Germany (BAOR - British Army of the Rhine), but in 1970 at the age of 9, I found myself in boarding school back in the UK. Three times a year I would fly from Luton to Gütersloh for school holidays. In 1976 my dad finished his time in the army and within a few months had secured an accompanied ex-pat role in Iran. I was 15. He was working for the Shah’s government in a military training school located in Masjed-I-Suleiman (known as MIS). As I was still in boarding school, all that changed was my route home for school holidays, instead of going to Germany I was flying unaccompanied from Heathrow to Abadan. And so, on to the main part of the story.

The main story - The content of this story comes from three sources; firstly, my own memories, some of which are clear as day and others which are a little more cloudy; secondly, snippets gained from my mother, some of them only very recently; thirdly, snippets from others who were there, which I collected at the time and stored away in my head forever.

The photos from Iran were all taken by my dad and are, to my knowledge, the only ones in existence.

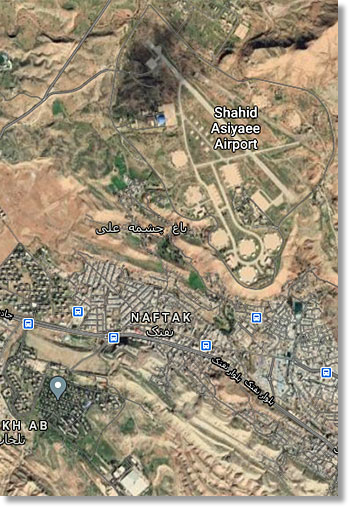

It was December 1978 and I was 17 years old. My family was living in Iran in a place called Masjed-I Suleiman (known as MIS) in Khuzestan province. MIS is located about 130km east of the border with Iraq, about 450km south west of Tehran and about 200km north east of Abadan which is at the north end of the Persian Gulf.

My dad was working for the Shah’s government in a technical military training school that was based upon the two REME technical training schools in the UK, Bordon and Arborfield.

Also located in MIS was an American company called BMY (Bowen McLaughlin York) who operated a tank repair facility. We all lived in a joint British-US community called Naftak just a few miles outside of MIS.

The photos from Iran were all taken by my dad and are, to my knowledge, the only ones in existence.

It was December 1978 and I was 17 years old. My family was living in Iran in a place called Masjed-I Suleiman (known as MIS) in Khuzestan province. MIS is located about 130km east of the border with Iraq, about 450km south west of Tehran and about 200km north east of Abadan which is at the north end of the Persian Gulf.

My dad was working for the Shah’s government in a technical military training school that was based upon the two REME technical training schools in the UK, Bordon and Arborfield.

Also located in MIS was an American company called BMY (Bowen McLaughlin York) who operated a tank repair facility. We all lived in a joint British-US community called Naftak just a few miles outside of MIS.

It's fair to say that life in Iran was rather different than the UK. We had a very nice large stone bungalow and we had a car, but no TV. Contact with the outside world was via the BBC World Service on a short-wave radio and newspapers that were at least a week old. We never heard BBC World Service news broadcasts because rather strangely there was always some loud interference on the radio whenever the news began, but other programmes were unaffected. Parts of the newspapers were usually overprinted with solid black rectangles to block out certain news stories. Welcome to the world of Iranian censorship.

As a result of this, most of the Naftak community knew absolutely nothing of the Islamic Revolution that had been developing over the preceding months. In boarding school I also saw very little of TV or newspapers, they did their best to ensure we were shielded from such distracting influences regardless of what was going on around the world, but I still saw some reports of the growing troubles in Iran.

Whenever I flew to Iran for school holidays from boarding school in the UK, it was usual for my mum to travel the 250km journey to the airport in a car with a company driver, to collect me and travel the 250km back again. It was also usual, if not extremely risky, for my relatives in the UK to stash a few uncensored newspapers in my suitcase. The likely consequences of being caught are quite unthinkable. On this occasion, my parents had been told that my dad would have to collect me instead. They asked why but were not told. It wasn’t for discussion, my mum had to stay at home.

I found out only recently that my parents had pre-ordered some Omega watches as Christmas presents from a shop in Abadan, so when my dad asked the driver to take him to the shop he said “No sir, we cannot”. My dad insisted and was taken to the shop. It was here that the first signs of trouble became apparent. The shopkeeper lifted the shutter, said “I’m glad you could make it”, handed over the watches and slammed the shutter. Very odd indeed. On the journey home I told my dad all that I knew. Everything I had seen on the news. The rioting and violence in Tehran, Isfahan and other cities - the arrests and the shootings - he was stunned. Why on earth had the company made arrangements to send kids in boarding schools home for Christmas and into an Islamic revolution? We arrived home and he got the newspapers out. He took them into the company offices and played hell with the management. They just accused him of causing trouble.

Over the following weeks, life began to change as rioting and violence took hold in MIS, however, it wasn’t until after Christmas that a plan to leave the country began to form. We all had a very good relationship with the local commanding officer of the Iranian army garrison but in January he said that it was becoming increasingly difficult to protect the British and American citizens, even from his own soldiers. He suggested that we should leave the country without delay. Now I’m unsure how exactly we found out about the two RAF C-130 aircraft based in Bahrain, nor how they were contacted. A vague story was heard that some of the British instructors in the telecommunications wing of the school had rigged some HF equipment and managed to talk to the aircraft crew, but I have no details. It may be untrue. My dad and our neighbour took a car in the evening to recce the local roads. They found the road out towards Ahvaz and Abadan was blocked, it was the same with the other routes out of town, but the road up to the local airport [Shahid Asiyaee] was clear. This was an almost completed new military airfield alongside the old airfield

As a result of this, most of the Naftak community knew absolutely nothing of the Islamic Revolution that had been developing over the preceding months. In boarding school I also saw very little of TV or newspapers, they did their best to ensure we were shielded from such distracting influences regardless of what was going on around the world, but I still saw some reports of the growing troubles in Iran.

Whenever I flew to Iran for school holidays from boarding school in the UK, it was usual for my mum to travel the 250km journey to the airport in a car with a company driver, to collect me and travel the 250km back again. It was also usual, if not extremely risky, for my relatives in the UK to stash a few uncensored newspapers in my suitcase. The likely consequences of being caught are quite unthinkable. On this occasion, my parents had been told that my dad would have to collect me instead. They asked why but were not told. It wasn’t for discussion, my mum had to stay at home.

I found out only recently that my parents had pre-ordered some Omega watches as Christmas presents from a shop in Abadan, so when my dad asked the driver to take him to the shop he said “No sir, we cannot”. My dad insisted and was taken to the shop. It was here that the first signs of trouble became apparent. The shopkeeper lifted the shutter, said “I’m glad you could make it”, handed over the watches and slammed the shutter. Very odd indeed. On the journey home I told my dad all that I knew. Everything I had seen on the news. The rioting and violence in Tehran, Isfahan and other cities - the arrests and the shootings - he was stunned. Why on earth had the company made arrangements to send kids in boarding schools home for Christmas and into an Islamic revolution? We arrived home and he got the newspapers out. He took them into the company offices and played hell with the management. They just accused him of causing trouble.

Over the following weeks, life began to change as rioting and violence took hold in MIS, however, it wasn’t until after Christmas that a plan to leave the country began to form. We all had a very good relationship with the local commanding officer of the Iranian army garrison but in January he said that it was becoming increasingly difficult to protect the British and American citizens, even from his own soldiers. He suggested that we should leave the country without delay. Now I’m unsure how exactly we found out about the two RAF C-130 aircraft based in Bahrain, nor how they were contacted. A vague story was heard that some of the British instructors in the telecommunications wing of the school had rigged some HF equipment and managed to talk to the aircraft crew, but I have no details. It may be untrue. My dad and our neighbour took a car in the evening to recce the local roads. They found the road out towards Ahvaz and Abadan was blocked, it was the same with the other routes out of town, but the road up to the local airport [Shahid Asiyaee] was clear. This was an almost completed new military airfield alongside the old airfield

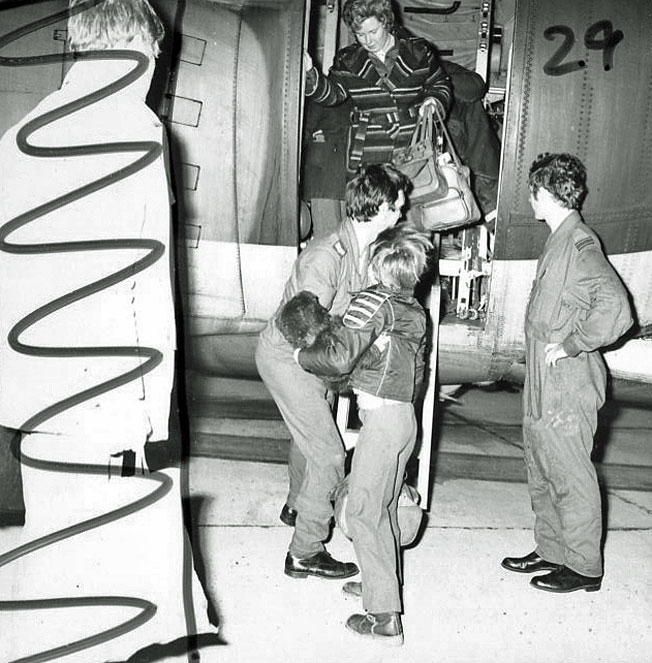

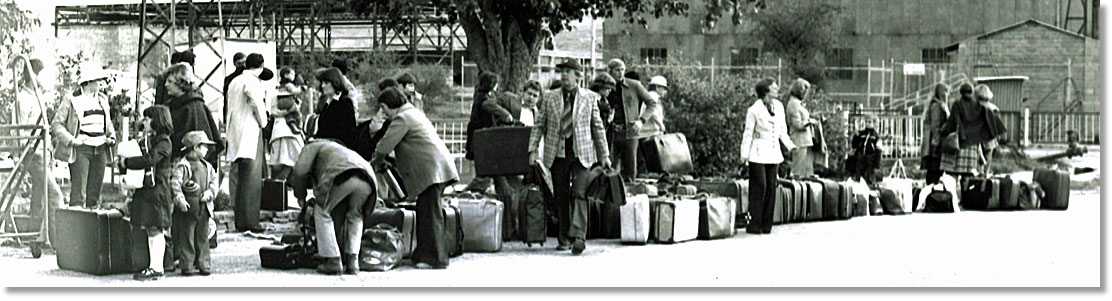

The plan was set, we would all drive to the airport before dawn and await the arrival of the C-130s. There must have been around fifty cars in convoy and nearly 200 people, British and American, with one suitcase each. We had been promised a military guard as an act of farewell.

As we prepared to leave the house around 5am, I had an idea. My brother and I each had a large Union Jack bedspread from the 1977 Queen’s Silver Jubilee celebrations. I grabbed mine, saying “I'm not leaving it here, they’ll only enjoy burning it”. Little did we know the great significance of that decision.

My brother grabbed his too and we set off. A great long convoy in the dark going up to the airport. Once there, daylight came and we waited a while under the trees near the old control tower building.

As we prepared to leave the house around 5am, I had an idea. My brother and I each had a large Union Jack bedspread from the 1977 Queen’s Silver Jubilee celebrations. I grabbed mine, saying “I'm not leaving it here, they’ll only enjoy burning it”. Little did we know the great significance of that decision.

My brother grabbed his too and we set off. A great long convoy in the dark going up to the airport. Once there, daylight came and we waited a while under the trees near the old control tower building.

After what seemed like ages, someone shouted and we could see a small dark smudge just above the horizon to the south east. As we watched, the smudge grew bigger and took the form of a big beautiful C-130. It roared over the runway at just a few hundred feet before circling round to the left and making a big loop to line up for landing.

Everyone was so excited, cheering and jumping up and down.

Suddenly, a woman said to me, “What’s that you’ve got there, a flag? Let's wave it!” so we did, jumping up and down waving this huge bedspread like a pair of excited idiots. The C-130 landed and taxied over to the hardstanding to our front.

We were saved. XV188 was here.

It all seemed pretty relaxed. The crew got out and did a few checks. We were told the second plane was about an hour behind and we were split into two groups. The rear ramp came down and we were told to hand over our luggage, which was piled on the ramp and secured with a net.

Everyone was so excited, cheering and jumping up and down.

Suddenly, a woman said to me, “What’s that you’ve got there, a flag? Let's wave it!” so we did, jumping up and down waving this huge bedspread like a pair of excited idiots. The C-130 landed and taxied over to the hardstanding to our front.

We were saved. XV188 was here.

It all seemed pretty relaxed. The crew got out and did a few checks. We were told the second plane was about an hour behind and we were split into two groups. The rear ramp came down and we were told to hand over our luggage, which was piled on the ramp and secured with a net.

Eventually we were allowed to board the aircraft and make ourselves comfortable on those nice red webbing seats.

To a 17-year-old lad, this was fantastic stuff. Minutes later we were airborne. I had a seat near the back on the left side with a small round window above my head.

Most of the flying was low level through mountainous valleys, presumably staying below any radar, until we got somewhere down towards Shiraz (apparently) where we turned to the south west and out over the gulf, eventually arriving at Bahrain International Airport.

I can’t remember how long it took, but it was around 800km.

To a 17-year-old lad, this was fantastic stuff. Minutes later we were airborne. I had a seat near the back on the left side with a small round window above my head.

Most of the flying was low level through mountainous valleys, presumably staying below any radar, until we got somewhere down towards Shiraz (apparently) where we turned to the south west and out over the gulf, eventually arriving at Bahrain International Airport.

I can’t remember how long it took, but it was around 800km.

Our luggage was almost the last to be taken off, so we were hanging around a short while. Someone had left a pushchair and some bags behind (isn't there always one!) so the crew asked us to wait and take them through. But instead of joining the queue with everyone else the crew said “Come with us.” So, we were out the other side first.

We then discovered we were to be accommodated overnight in the same hotel as the RAF crew and they said there was a swimming pool on the roof. Bonus! British Airways flights to Heathrow were booked for the following day.

We were taken to the hotel by bus and before very long we were in that swimming pool. It didn’t take long to discover the aircrew were there on sun loungers with cold drinks. Life in the RAF hey!

Then came the most incredible news. One of the crew asked, “Whose idea was it to wave that huge flag?”

I responded, “Oh, it wasn’t a planned idea, just excitement, and it’s my bedspread that I didn’t want to leave behind.”

“Well it’s a good job you did,” said one of the aircrew, “because we came in over the airfield to check it out, we saw all the armed soldiers and thought this looks very dodgy so we turned around to bug out, then we spotted the people under the trees and the flag being waved and said shall we chance it? Yes, OK, but the first sign of shooting and we’re off!”

So we were very lucky indeed, it could’ve ended so very differently.

Another story was circulated a little while later, that one of the aircraft was intercepted by a pair of Iranian F-4s over the Gulf, who demanded the C-130 turn around and land at Shiraz (allegedly). This also may be untrue, I cannot verify it. The story went that the C-130 pilot ignored their demands for a while before replying something like “Iran air force fighter aircraft, this is Royal Air Force C-130, we are now out of your airspace, good day”. If that is true, the man has balls of steel.

So, all’s well that ends well. We are still alive 41 years later. I have some good memories and some interesting photographs.

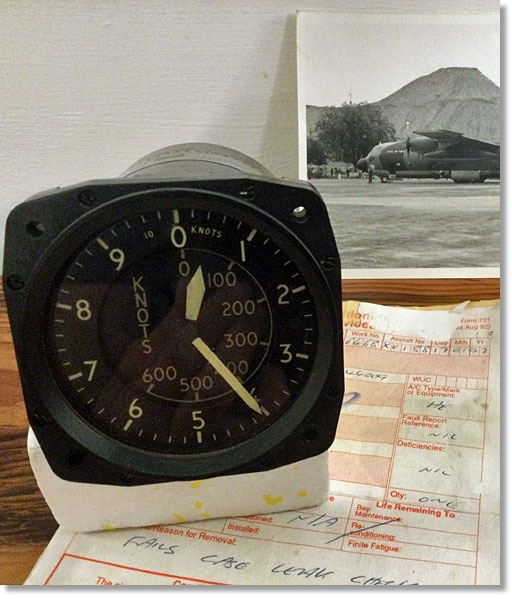

I was saddened to learn that XV188 was retired and broken up a few years ago, but I found its airspeed indicator for sale on e-Bay, which now sits on my bookshelf. And I still have the Union Jack bedspread.

If anyone here was involved in that operation and would like to share their part of the story, please do. I would love to hear from you.

Tim J.

We then discovered we were to be accommodated overnight in the same hotel as the RAF crew and they said there was a swimming pool on the roof. Bonus! British Airways flights to Heathrow were booked for the following day.

We were taken to the hotel by bus and before very long we were in that swimming pool. It didn’t take long to discover the aircrew were there on sun loungers with cold drinks. Life in the RAF hey!

Then came the most incredible news. One of the crew asked, “Whose idea was it to wave that huge flag?”

I responded, “Oh, it wasn’t a planned idea, just excitement, and it’s my bedspread that I didn’t want to leave behind.”

“Well it’s a good job you did,” said one of the aircrew, “because we came in over the airfield to check it out, we saw all the armed soldiers and thought this looks very dodgy so we turned around to bug out, then we spotted the people under the trees and the flag being waved and said shall we chance it? Yes, OK, but the first sign of shooting and we’re off!”

So we were very lucky indeed, it could’ve ended so very differently.

Another story was circulated a little while later, that one of the aircraft was intercepted by a pair of Iranian F-4s over the Gulf, who demanded the C-130 turn around and land at Shiraz (allegedly). This also may be untrue, I cannot verify it. The story went that the C-130 pilot ignored their demands for a while before replying something like “Iran air force fighter aircraft, this is Royal Air Force C-130, we are now out of your airspace, good day”. If that is true, the man has balls of steel.

So, all’s well that ends well. We are still alive 41 years later. I have some good memories and some interesting photographs.

I was saddened to learn that XV188 was retired and broken up a few years ago, but I found its airspeed indicator for sale on e-Bay, which now sits on my bookshelf. And I still have the Union Jack bedspread.

If anyone here was involved in that operation and would like to share their part of the story, please do. I would love to hear from you.

Tim J.

From: Bruce Oram, San Fulgencio, Alicante

Subject: Iran Evacuations

Here are my recollections from 41 years ago on the Iran evacuations. There were 6 MAMS personnel involved being, Flt Lt Guy Blythe, Cpl Bob Thacker and Cpl Bruce Oram on one aircraft and I think the other team was Flt Lt Tom James, Cpl Gus Cobb and A N Other. We were accommodated in the Hotel Vendome in Manama.

The crew I flew with were Andy Potter, Ray Evans, Jinx Newman, Martin Simmons, George Fair and Dave Pyne (all 30 Sqn). Our first trip into Iran came on the morning of 16 January 1979, setting off for a place called Majeid Sulieman which was in the mountains. There being no radar, everyone on board was busy looking out of every window possible often looking up at shepherds on the surrounding hills. As we got nearer to our destination we could see smoke in the distance, apparently from the town. Then we spotted the runway and the airport building with a huge Union Jack flag on the roof.

I had hooked a net to the forward edge of the ramp so the evacuees carrying a bag each could drop it to me and proceed to a seat. The local British priest had already checked all the passports to verify who the people were. This was all done at high speed (25 minutes). I hooked the rear end of the net as we taxied to the runway. The net was secured as we did our run for take-off. It was then the job of writing out a manifest of those on board amid all the cheers. On landing in Bahrain we readied the aircraft just in case we were required the next day. The evacuees were accommodated in the Vendome Hotel also and met us in the bar that night.

My second trip into Iran came on the 24 Jan 1979 to a place called Awaz which was carried out in a similar manner but a little slower as we loaded 65 evacuees back to Bahrain.

Subject: Iran Evacuations

Here are my recollections from 41 years ago on the Iran evacuations. There were 6 MAMS personnel involved being, Flt Lt Guy Blythe, Cpl Bob Thacker and Cpl Bruce Oram on one aircraft and I think the other team was Flt Lt Tom James, Cpl Gus Cobb and A N Other. We were accommodated in the Hotel Vendome in Manama.

The crew I flew with were Andy Potter, Ray Evans, Jinx Newman, Martin Simmons, George Fair and Dave Pyne (all 30 Sqn). Our first trip into Iran came on the morning of 16 January 1979, setting off for a place called Majeid Sulieman which was in the mountains. There being no radar, everyone on board was busy looking out of every window possible often looking up at shepherds on the surrounding hills. As we got nearer to our destination we could see smoke in the distance, apparently from the town. Then we spotted the runway and the airport building with a huge Union Jack flag on the roof.

I had hooked a net to the forward edge of the ramp so the evacuees carrying a bag each could drop it to me and proceed to a seat. The local British priest had already checked all the passports to verify who the people were. This was all done at high speed (25 minutes). I hooked the rear end of the net as we taxied to the runway. The net was secured as we did our run for take-off. It was then the job of writing out a manifest of those on board amid all the cheers. On landing in Bahrain we readied the aircraft just in case we were required the next day. The evacuees were accommodated in the Vendome Hotel also and met us in the bar that night.

My second trip into Iran came on the 24 Jan 1979 to a place called Awaz which was carried out in a similar manner but a little slower as we loaded 65 evacuees back to Bahrain.

The final run into Iran came on 31 Jan 1979, destination Tehran. Getting closer to our destination we could see the aircraft below us spiralling down towards the runway. After landing and parking up, I proceeded to manifest 71 evacuees. Whilst doing this I felt a rumbling where I was sat. This apparently was a tank and armoured cars racing across the airport as there was some trouble beginning. I quickly finished the manifest and helped Bob secure the bags and load the evacuees. We landed back at Bahrain to the delight of all our passengers on board.

Cheers the noo! Bruce

Cheers the noo! Bruce

From: Tim James, Boston, Lincs

Subject: Escape from Iran - Follow up

Subject: Escape from Iran - Follow up

Wow, that is about as close as it gets! The date Bruce has given tallies exactly with what my mother told me last week, how they remember that I'll never know. I had figured it was sometime in January because I was due back at boarding school and missed the start of term.

After 41 years you might expect there to be a few differences between two accounts of the same event, particularly from two opposing perspectives, but the only comment I would make is that the huge Union Jack wasn't on the roof because I was holding it and we were not far from the front of the BMY hangar, but that could easily be mistaken from the air.

I wasn't aware of the smoke that Bruce mentions because we stayed away from the town and I'm pretty sure it was only just getting light as we drove up there. No surprise though, probably the result of some rioting the previous evening.

The journey to the airfield was only about 7km though my mother tells me that one of the still serving British Army officers had decided to take charge of the road move and promptly got everyone lost, ending up in a quarry. I don't remember that.

I'm not entirely sure what time the aircraft arrived, or was due to arrive. I have it in my head it was 0800 but I could be wrong. I'm sure we weren't waiting more than about an hour, probably less.

Interesting comment about there being no radar. Did Bruce mean the Iranians had no radar or the C-130 had no radar? We were under the impression the Iranians did have radar hence the need for low level flying, but I'm not going to dispute that.

I seem to remember there was still activity with the cargo net on the ramp as the aircraft was rolling, as I was sat very near the back, so I probably saw Bruce.

I also have a vague recollection of someone shouting three cheers for the RAF; Bruce said there was a load of cheering.

I can also remember needing a pee during the flight and being directed by a crewman at the rear to climb up on top of the centre row of seats and walk along to the front, sort of tightrope style, because the toilet was near the cockpit. Good excuse for a brief cockpit visit too. I wish I had taken photos.

Really good to read Bruce's report. I shall relay it on to my family and if I ever go to Benidorm I'll buy him a few beers!

Best regards,

Tim

After 41 years you might expect there to be a few differences between two accounts of the same event, particularly from two opposing perspectives, but the only comment I would make is that the huge Union Jack wasn't on the roof because I was holding it and we were not far from the front of the BMY hangar, but that could easily be mistaken from the air.

I wasn't aware of the smoke that Bruce mentions because we stayed away from the town and I'm pretty sure it was only just getting light as we drove up there. No surprise though, probably the result of some rioting the previous evening.

The journey to the airfield was only about 7km though my mother tells me that one of the still serving British Army officers had decided to take charge of the road move and promptly got everyone lost, ending up in a quarry. I don't remember that.

I'm not entirely sure what time the aircraft arrived, or was due to arrive. I have it in my head it was 0800 but I could be wrong. I'm sure we weren't waiting more than about an hour, probably less.

Interesting comment about there being no radar. Did Bruce mean the Iranians had no radar or the C-130 had no radar? We were under the impression the Iranians did have radar hence the need for low level flying, but I'm not going to dispute that.

I seem to remember there was still activity with the cargo net on the ramp as the aircraft was rolling, as I was sat very near the back, so I probably saw Bruce.

I also have a vague recollection of someone shouting three cheers for the RAF; Bruce said there was a load of cheering.

I can also remember needing a pee during the flight and being directed by a crewman at the rear to climb up on top of the centre row of seats and walk along to the front, sort of tightrope style, because the toilet was near the cockpit. Good excuse for a brief cockpit visit too. I wish I had taken photos.

Really good to read Bruce's report. I shall relay it on to my family and if I ever go to Benidorm I'll buy him a few beers!

Best regards,

Tim

The airspeed indicator from Hercules XV188 which

I found on e-Bay and now resides on my bookshelf

I found on e-Bay and now resides on my bookshelf

The Union Jack bedspread that literally saved

the day back in '79 is now a family heirloom.

the day back in '79 is now a family heirloom.

From: Charlie Marlow, Freshwater, Isle of Wight

Subject: Re: Movements Officers' Reunion 2020

What a shame that the reunion had to be canceled; very disappointing for all those who were hoping to attend. However, these unprecedented times have brought disappointment to many. Serving and ex-service men and women don’t always need reunions to maintain friendships and camaraderie. We are all acutely aware that out of sight is not out of mind and when we do reunite it’s as though we’d never been apart.

Subject: Re: Movements Officers' Reunion 2020

What a shame that the reunion had to be canceled; very disappointing for all those who were hoping to attend. However, these unprecedented times have brought disappointment to many. Serving and ex-service men and women don’t always need reunions to maintain friendships and camaraderie. We are all acutely aware that out of sight is not out of mind and when we do reunite it’s as though we’d never been apart.

World's last Blackburn Beverley aircraft saved by plan to create amazing holiday let

The businessman who has saved the world’s last Blackburn Beverley aircraft from the scrap heap has revealed plans to turn it into a unique Airbnb let – with a jacuzzi in the nose cone. Pilot Martyn Wiseman, who has an airfield near Selby, Birchwood Lodge, bought the giant aircraft at auction earlier this month. having had his eye on it for a year.

Mr Wiseman has already converted an eight-seater Hawker executive plane, which was once at the beck and call of the Russian jet set, into a luxury crash pad. It featured on George Clarke’s Channel 4 show Amazing Spaces. But those plans are dwarfed by his vision for the transport plane, which will take six months to dismantle – the engines weigh two tonnes each – and then move by crane and lowloader from Paull Fort to his airfield. There is even a possibility the parts could get flown the 33 miles distance if the RAF decides to get its heavy-lift Chinook helicopter fleet involved.

The conversion will see the area where the paratroopers once waited to jump turned into two bedrooms, while the main cargo hold – which could carry 94 troops – will be a kitchen and dining area. And for the evening G&T where else? The cockpit where the pilot and co-pilots seats will be reupholstered and put on swivels, and guests can watch as aircraft land on Mr Wiseman’s runway.

Some people had hoped it would remain a museum, but Mr Wiseman said “simple commercial reality” had to prevail. Nothing would be thrown away, with some internal fittings going on display in a separate building. Mr Wiseman, who has a civil engineering firm and also makes bespoke experimental designs for light aircraft, said: “You have to be realistic. As a museum it’s not an attraction – people will come once and that’s it.

The Beverley Association, for former aircrew and groundcrew, he said, were very supportive and “quite relaxed about getting it modernised to preserve it.”

Yorkshire Post

Mr Wiseman has already converted an eight-seater Hawker executive plane, which was once at the beck and call of the Russian jet set, into a luxury crash pad. It featured on George Clarke’s Channel 4 show Amazing Spaces. But those plans are dwarfed by his vision for the transport plane, which will take six months to dismantle – the engines weigh two tonnes each – and then move by crane and lowloader from Paull Fort to his airfield. There is even a possibility the parts could get flown the 33 miles distance if the RAF decides to get its heavy-lift Chinook helicopter fleet involved.

The conversion will see the area where the paratroopers once waited to jump turned into two bedrooms, while the main cargo hold – which could carry 94 troops – will be a kitchen and dining area. And for the evening G&T where else? The cockpit where the pilot and co-pilots seats will be reupholstered and put on swivels, and guests can watch as aircraft land on Mr Wiseman’s runway.

Some people had hoped it would remain a museum, but Mr Wiseman said “simple commercial reality” had to prevail. Nothing would be thrown away, with some internal fittings going on display in a separate building. Mr Wiseman, who has a civil engineering firm and also makes bespoke experimental designs for light aircraft, said: “You have to be realistic. As a museum it’s not an attraction – people will come once and that’s it.

The Beverley Association, for former aircrew and groundcrew, he said, were very supportive and “quite relaxed about getting it modernised to preserve it.”

Yorkshire Post

From: Jeremy Babington, Frome, Somerset

Subject: Repatriations

Tony,

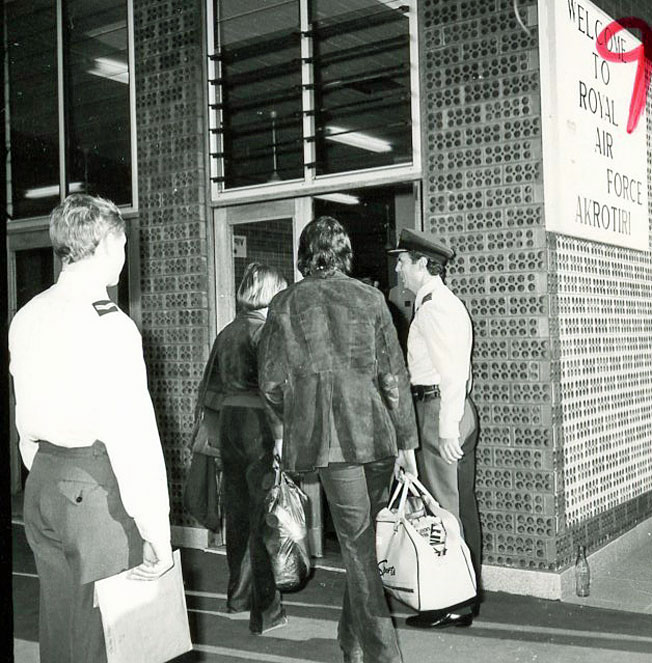

I recall, with hazy memory, the evacuation of British nationals from Cyprus in 1974. I had just joined UKMAMS and as an officer with no team was sent out to reinforce the other MAMS teams who were already there living in 12 by 12 tents outside of Load Control.

I was the only passenger on a Comet during the outbound flight and remember a slight sense of alarm when all the lights were doused 200 miles out from landing.

I spent about 4 weeks there helping to offload inbound flights and embarking many distraught passengers for the flight home some of whom had come straight from the beaches.

My abiding memory though will be the utter frustration of unloading APCs from inbound UK flights only to load them on to 70 Sqn aircraft (the only dirt-strip qualified C130 Sqn) for onward flight to Kingsfield, Dhekhelia for REME checks. Many of them subsequently arrived back at Akrotiri by air for operation! Unload, load, unload. Lots of chains and in oppressive heat.

Best wishes to all in these strange times,

Jerry Babington

Subject: Repatriations

Tony,

I recall, with hazy memory, the evacuation of British nationals from Cyprus in 1974. I had just joined UKMAMS and as an officer with no team was sent out to reinforce the other MAMS teams who were already there living in 12 by 12 tents outside of Load Control.

I was the only passenger on a Comet during the outbound flight and remember a slight sense of alarm when all the lights were doused 200 miles out from landing.

I spent about 4 weeks there helping to offload inbound flights and embarking many distraught passengers for the flight home some of whom had come straight from the beaches.

My abiding memory though will be the utter frustration of unloading APCs from inbound UK flights only to load them on to 70 Sqn aircraft (the only dirt-strip qualified C130 Sqn) for onward flight to Kingsfield, Dhekhelia for REME checks. Many of them subsequently arrived back at Akrotiri by air for operation! Unload, load, unload. Lots of chains and in oppressive heat.

Best wishes to all in these strange times,

Jerry Babington

From: Tony Mullen, Toowoomba, QLD

Subject: Evacuation of British Nationals from East Pakistan

Subject: Evacuation of British Nationals from East Pakistan

In 1965 Pakistan and India were at war. East Pakistan was what is now independent Bangladesh. The British Government decided that the risk of casualties in East Pakistan was significant and that British ex-pats should be offered temporary residence in Singapore.

A Britannia aircraft from 99 Sqn at Lyneham was put on standby at Changi and a FEAF MAMS team was assigned to the task. I was the team leader. We were instructed to report to the Changi Transit Hotel at “sparrows” and wait for the signal that the operation was to proceed. We were told to be prepared for a two or three day stay at Dacca because some three evacuation flights were planned. We were also told to have a tent and rations with us as accommodation was unlikely.

We waited some four hours at Changi until advised that the operation was postponed and we were to repeat the standby at Changi the following day. Again we were stood down but on the 3rd day we got the green light. We loaded our camping equipment on board the Britannia bound for the capital of East Pakistan, Dacca.

On arrival we were met by a Pakistan Air Force Sqn Ldr and a hundred or so British women and children. I asked the Sqn Ldr where we could pitch our MAMS tent and was politely but very firmly advised that we were not permitted to remain there under any circumstances and must return on the aircraft once we had loaded the baggage and embarked the passengers!

This we did but the aircraft was at full capacity and we had to sit on the floor for the return trip. Another MAMS team was assigned for the other two flights.

Obviously, the planning of the operation was very poor. The Air Staff forgot to get authorisation for the MAMS team to remain at Dacca. All very amateur in hindsight.

Best regards

Tony Mullen

A Britannia aircraft from 99 Sqn at Lyneham was put on standby at Changi and a FEAF MAMS team was assigned to the task. I was the team leader. We were instructed to report to the Changi Transit Hotel at “sparrows” and wait for the signal that the operation was to proceed. We were told to be prepared for a two or three day stay at Dacca because some three evacuation flights were planned. We were also told to have a tent and rations with us as accommodation was unlikely.

We waited some four hours at Changi until advised that the operation was postponed and we were to repeat the standby at Changi the following day. Again we were stood down but on the 3rd day we got the green light. We loaded our camping equipment on board the Britannia bound for the capital of East Pakistan, Dacca.

On arrival we were met by a Pakistan Air Force Sqn Ldr and a hundred or so British women and children. I asked the Sqn Ldr where we could pitch our MAMS tent and was politely but very firmly advised that we were not permitted to remain there under any circumstances and must return on the aircraft once we had loaded the baggage and embarked the passengers!

This we did but the aircraft was at full capacity and we had to sit on the floor for the return trip. Another MAMS team was assigned for the other two flights.

Obviously, the planning of the operation was very poor. The Air Staff forgot to get authorisation for the MAMS team to remain at Dacca. All very amateur in hindsight.

Best regards

Tony Mullen

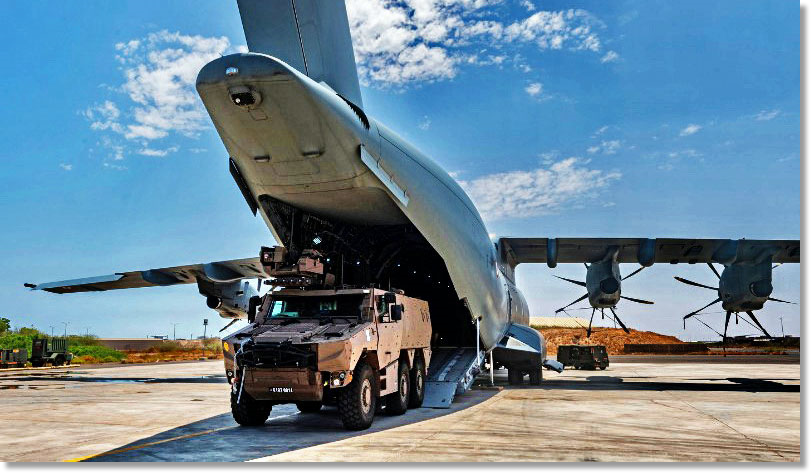

A400M transports Griffon armoured vehicle from Djibouti

As part of an operational trial, an A400M Atlas transport aircraft of the French Air and Space Force transported for the first time a Griffon armoured vehicle from Djibouti to Orleans, France.

The operation proved tricky, considering the sheer weight (20.8 tonnes for 37 tonnes of load capacity of the A400M Atlas) and the size of the Griffon.

defenceweb.co.za

The operation proved tricky, considering the sheer weight (20.8 tonnes for 37 tonnes of load capacity of the A400M Atlas) and the size of the Griffon.

defenceweb.co.za

From: Allison Bell, Toronto, ON

Subject: Terry Bell

Hello Tony,

My late Dad, Terry Bell, passed way in May 2018. Several of his RAF mates were in touch with him over the last several years, and it made him so happy!

The purpose of my email is that my Mom, Wendy, has a couple of upcoming milestones in November. Her and my Dad would’ve celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary on November 14th, and her 70th birthday is 3 days later on November 17th. She’s an incredible woman who has lost her incredible life-partner, and I’m trying to make these milestones as special as possible when she’s not got my Dad to celebrate with.

I was hoping that some of Dad’s old RAF buddies could send her a card to let her know she’s cared about; I believe that there’s somewhat of a brethren mentality with RAF folks, so I thought this may be a possibility.

If any of you are able/willing to send her a card, I’m going to receive the cards at my home so as to surprise her:

Wendy Bell

112 Delaware Ave

Toronto, ON, M6H 2T1

Canada

Thank you so very much in advance, Allison Bell

Subject: Terry Bell

Hello Tony,

My late Dad, Terry Bell, passed way in May 2018. Several of his RAF mates were in touch with him over the last several years, and it made him so happy!

The purpose of my email is that my Mom, Wendy, has a couple of upcoming milestones in November. Her and my Dad would’ve celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary on November 14th, and her 70th birthday is 3 days later on November 17th. She’s an incredible woman who has lost her incredible life-partner, and I’m trying to make these milestones as special as possible when she’s not got my Dad to celebrate with.

I was hoping that some of Dad’s old RAF buddies could send her a card to let her know she’s cared about; I believe that there’s somewhat of a brethren mentality with RAF folks, so I thought this may be a possibility.

If any of you are able/willing to send her a card, I’m going to receive the cards at my home so as to surprise her:

Wendy Bell

112 Delaware Ave

Toronto, ON, M6H 2T1

Canada

Thank you so very much in advance, Allison Bell

Helicopter delivered in time for fire season

A trans-Pacific mission by an Air Force C-17A Globemaster has delivered a Bell 412 helicopter for the NSW Rural Fire Service.

Loaded by a No. 36 Squadron C-17A crew at Vancouver International Airport, Canada, the Bell 412 was delivered to RAAF Base Richmond where it was reconstructed and received additional servicing. The Bell 412 will be ready to combat bushfires this summer.

Commander Air Mobility Group Air Commodore Carl Newman said the mission was well-suited to the C-17A’s capabilities. “One of the reasons that Defence purchased the C-17A was the aircraft’s ability to transport large loads like this helicopter over great distances, where and when they were needed,” Air Commodore Newman said. “Using a C-17A to carry a Bell 412 across the Pacific is an outstanding example of a Defence asset in support of another government agency and one that will yield positive results for the broader Australian community. “Our air mobility fleet has a strong record of supporting state-based emergency services, including during Operation Bushfire Assist, and we will continue providing support.”

It was the first time an Australian crew had transported a three-tonne Bell 412. A special cargo instruction on how to safely load, restrain, and unload the helicopter was provided by Air Mobility Training and Development Unit.

news.defence.gov.au

Loaded by a No. 36 Squadron C-17A crew at Vancouver International Airport, Canada, the Bell 412 was delivered to RAAF Base Richmond where it was reconstructed and received additional servicing. The Bell 412 will be ready to combat bushfires this summer.

Commander Air Mobility Group Air Commodore Carl Newman said the mission was well-suited to the C-17A’s capabilities. “One of the reasons that Defence purchased the C-17A was the aircraft’s ability to transport large loads like this helicopter over great distances, where and when they were needed,” Air Commodore Newman said. “Using a C-17A to carry a Bell 412 across the Pacific is an outstanding example of a Defence asset in support of another government agency and one that will yield positive results for the broader Australian community. “Our air mobility fleet has a strong record of supporting state-based emergency services, including during Operation Bushfire Assist, and we will continue providing support.”

It was the first time an Australian crew had transported a three-tonne Bell 412. A special cargo instruction on how to safely load, restrain, and unload the helicopter was provided by Air Mobility Training and Development Unit.

news.defence.gov.au

THE ROYAL HAIR FORCE:

The Royal Air Force are allowing its airmen to keep dreadlocks, braids and ponytails in a bid to boost diversity in the service. From now on the fashion-conscious can also keep cornrows and twists should they wish. The new rules follow close on the heels of the force allowing its airmen to grow beards for the first time in its 101-year history last September. It's hoped the changes to their 'hair policy' will help promote inclusivity and broaden the RAF's recruitment pool.

The changes could see airmen rocking a number of hipster hairstyles including mullets, ponytails and man-buns. But standards will not be slipping as there will be strict regulations to keep out wacky designs. Irrespective of their gender, hair in any style will have to be capped by the bottom edge of the collar.

Those with extra long or big hair will have to wrap it up in non-religious turbans if it fails to tuck neatly under peaked caps or berets. And the turbans in question must be of an 'approved service pattern and colour' featuring a cap badge front and centre.

The RAF is the least diverse of the three armed forces and hopes that by allowing the new hair-do's it will reflect society and attract people from diverse backgrounds. The new hair policy is all about moving with the times and bringing the RAF into the 21st century. A spokesman said it was all about moving with the times adding "This is one important step, of many, to deliver a next-generation Air Force fit for the 21st century."

Prior to the new rules, non-regulation styles were approved only on religious grounds. Last year, as well as making changes to their 'facial hair policy' by allowing beards, the RAF also relaxed tattoo rules to allow ink on eyebrows, neck and hands.

Daily Mail Online

The changes could see airmen rocking a number of hipster hairstyles including mullets, ponytails and man-buns. But standards will not be slipping as there will be strict regulations to keep out wacky designs. Irrespective of their gender, hair in any style will have to be capped by the bottom edge of the collar.

Those with extra long or big hair will have to wrap it up in non-religious turbans if it fails to tuck neatly under peaked caps or berets. And the turbans in question must be of an 'approved service pattern and colour' featuring a cap badge front and centre.

The RAF is the least diverse of the three armed forces and hopes that by allowing the new hair-do's it will reflect society and attract people from diverse backgrounds. The new hair policy is all about moving with the times and bringing the RAF into the 21st century. A spokesman said it was all about moving with the times adding "This is one important step, of many, to deliver a next-generation Air Force fit for the 21st century."

Prior to the new rules, non-regulation styles were approved only on religious grounds. Last year, as well as making changes to their 'facial hair policy' by allowing beards, the RAF also relaxed tattoo rules to allow ink on eyebrows, neck and hands.

Daily Mail Online

From: Bernie Lafrance, Nanaimo, BC

Subject: UN Tour Egypt

I was posted to UN Egypt from the Fall of 1975 to the Spring of 1976. On arrival in camp I was immediately dispatched to Beirut, Lebanon, as part of the Beirut MAMS team dealing with passengers and freight on R&R in Beirut and back to Egypt, on a Bi-weekly schedule.

The situation for two months was fine and things were working well, but in my 3rd month things turned sour between two local factions. Every so often missiles would be sent toward the city hitting different parts. We were not too sure what was going on as most people were speaking Arabic which we didn’t understand and as it turned out, the rockets were being fired into the brand new Holiday Inn, setting it on fire and destroying it. I forgot to mention that every time we went to and from the airport we had to drive past Arafat’s camp which increased our discomfort.

We were staying at the Charles Hotel, approximately 1 km from the Holiday Inn, and it was quite comfortable when one night a replacement came in and told our group that we had to move to another location. We challenged the move but moved the next day anyway and that night the Charles Hotel was hit. Lucky for us that day.

Things were not getting any better because we were placed on a nightly curfew from 2000 hrs to 0600 hrs. Soon after our move, the Canadian Embassy staff requested our assistance to evacuate them and their families to the airport and we followed through and completed the move easily. As things went, a few days later, the Canadian Military Attaché, a friend of mine, requested assistance to evacuate them also. Shortly afterwards I was sent to Damascus, Syria for one month.

Cheers, Bernie

Subject: UN Tour Egypt

I was posted to UN Egypt from the Fall of 1975 to the Spring of 1976. On arrival in camp I was immediately dispatched to Beirut, Lebanon, as part of the Beirut MAMS team dealing with passengers and freight on R&R in Beirut and back to Egypt, on a Bi-weekly schedule.

The situation for two months was fine and things were working well, but in my 3rd month things turned sour between two local factions. Every so often missiles would be sent toward the city hitting different parts. We were not too sure what was going on as most people were speaking Arabic which we didn’t understand and as it turned out, the rockets were being fired into the brand new Holiday Inn, setting it on fire and destroying it. I forgot to mention that every time we went to and from the airport we had to drive past Arafat’s camp which increased our discomfort.

We were staying at the Charles Hotel, approximately 1 km from the Holiday Inn, and it was quite comfortable when one night a replacement came in and told our group that we had to move to another location. We challenged the move but moved the next day anyway and that night the Charles Hotel was hit. Lucky for us that day.

Things were not getting any better because we were placed on a nightly curfew from 2000 hrs to 0600 hrs. Soon after our move, the Canadian Embassy staff requested our assistance to evacuate them and their families to the airport and we followed through and completed the move easily. As things went, a few days later, the Canadian Military Attaché, a friend of mine, requested assistance to evacuate them also. Shortly afterwards I was sent to Damascus, Syria for one month.

Cheers, Bernie

From: Kate O’Brien

Subject: Chris Swaithes

Hi Tony,

Hope you are well. I am emailing you as I’m currently looking for information, pictures, stories, memories or anything regarding my Grandad, Chris Swaithes, who I believe worked in the UKMAMS up until around the early 90’s.

I know it would mean so much to him if I could find anything for him to read over or look at, it would be very nostalgic and I would love to be able to help bring back all his wonderful memories. Is this something you would be able to help with?

Thank you so much for your time.

Kind regards,

Kate O’Brien

Subject: Chris Swaithes

Hi Tony,

Hope you are well. I am emailing you as I’m currently looking for information, pictures, stories, memories or anything regarding my Grandad, Chris Swaithes, who I believe worked in the UKMAMS up until around the early 90’s.

I know it would mean so much to him if I could find anything for him to read over or look at, it would be very nostalgic and I would love to be able to help bring back all his wonderful memories. Is this something you would be able to help with?

Thank you so much for your time.

Kind regards,

Kate O’Brien

(Click on the flag next to Kate's name to send an e-mail to her)

RCAF 60 Years Hercules Anniversary

On 13 October 2020, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) celebrated sixty years of operation with the Lockheed C-130 Hercules.

A ceremony and a flypast were held at CFB Winnipeg to celebrate six decades of flying with the well-known transporter. Back in 1960, 435 squadron was the first Canadian unit to receive the C-130, when four C-130Bs were delivered.

Although the career of the B-model lasted for only six years, with the remaining three aircraft sold in 1967, the introduction set the mark for the next sixty years of flying the Herk with 435 squadron.

The B-model was followed by the E-model, and with both early models retired, the RCAF still operates the CC-130H and CC-130J as the transporters became known under the Canadian military designation system in the late sixties. Such is the span that three generations of Canadian airmen have flown the Hercules and a total of 59 different airframes have been operated by the RCAF.

The Hercules is used in Canada in a variety of roles, mostly as cargo haulers, but 435 squadron is tasked with fighter support by providing an air-to-air refuelling capability to the CF-18 fighter community. Another important role in Canada is Search And Rescue (SAR), in which the older H-models are operated from Trenton ON, and Greenwood, NS. Their tasks will be taken over by the recently acquired CC-295 Kingfisher Fixed Wing SAR aircraft.

The anniversary was celebrated with a flypast, including a Hercules and two CF-18 fighters over Winnipeg.

scramble.nl

A ceremony and a flypast were held at CFB Winnipeg to celebrate six decades of flying with the well-known transporter. Back in 1960, 435 squadron was the first Canadian unit to receive the C-130, when four C-130Bs were delivered.

Although the career of the B-model lasted for only six years, with the remaining three aircraft sold in 1967, the introduction set the mark for the next sixty years of flying the Herk with 435 squadron.

The B-model was followed by the E-model, and with both early models retired, the RCAF still operates the CC-130H and CC-130J as the transporters became known under the Canadian military designation system in the late sixties. Such is the span that three generations of Canadian airmen have flown the Hercules and a total of 59 different airframes have been operated by the RCAF.

The Hercules is used in Canada in a variety of roles, mostly as cargo haulers, but 435 squadron is tasked with fighter support by providing an air-to-air refuelling capability to the CF-18 fighter community. Another important role in Canada is Search And Rescue (SAR), in which the older H-models are operated from Trenton ON, and Greenwood, NS. Their tasks will be taken over by the recently acquired CC-295 Kingfisher Fixed Wing SAR aircraft.

The anniversary was celebrated with a flypast, including a Hercules and two CF-18 fighters over Winnipeg.

scramble.nl

From: Ian Envis, Crowborough, East Sussex

Subject: Iran Airlift 1979 - AKT Movements

Hi Tony,

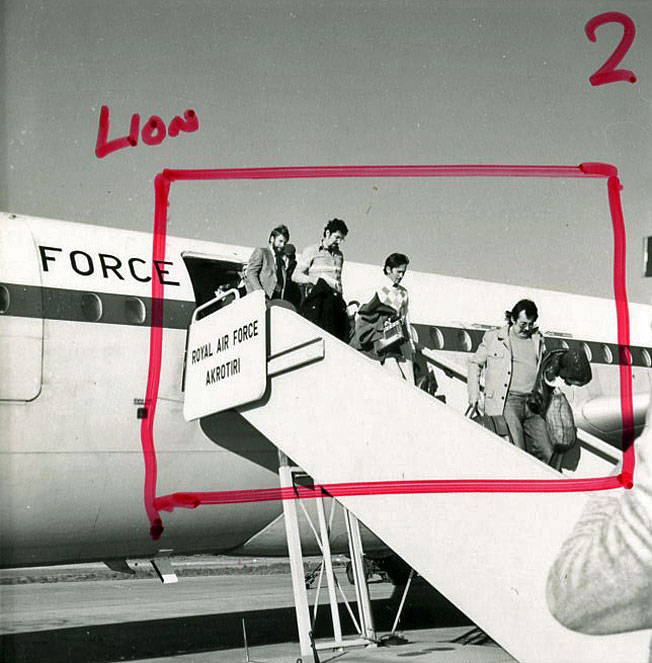

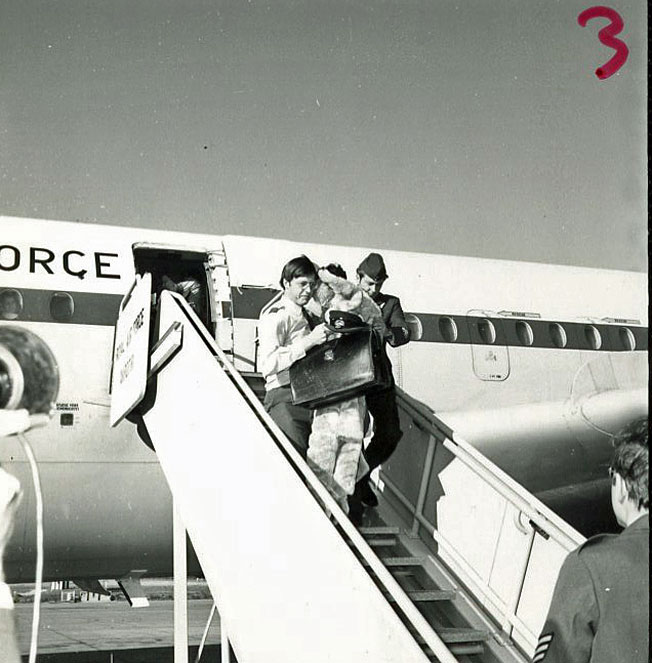

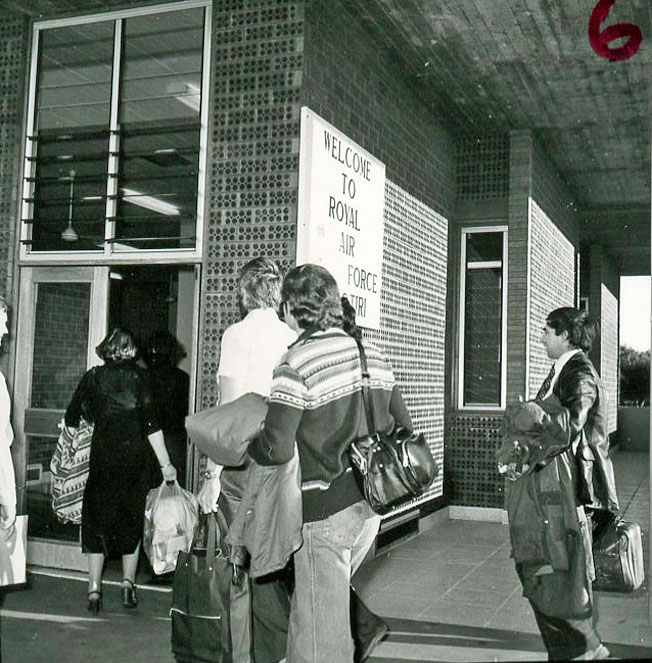

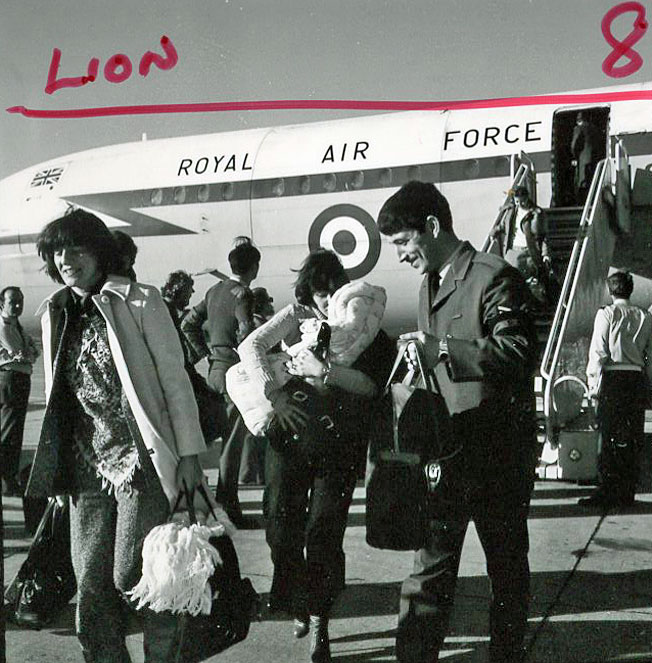

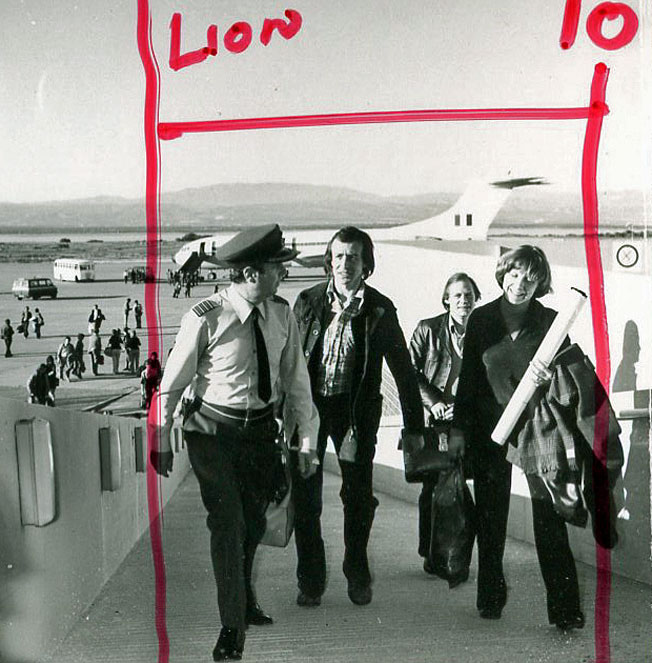

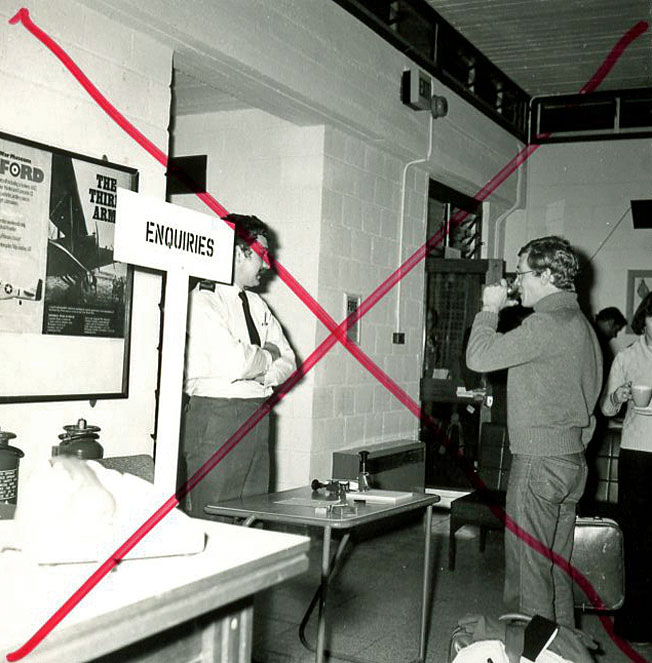

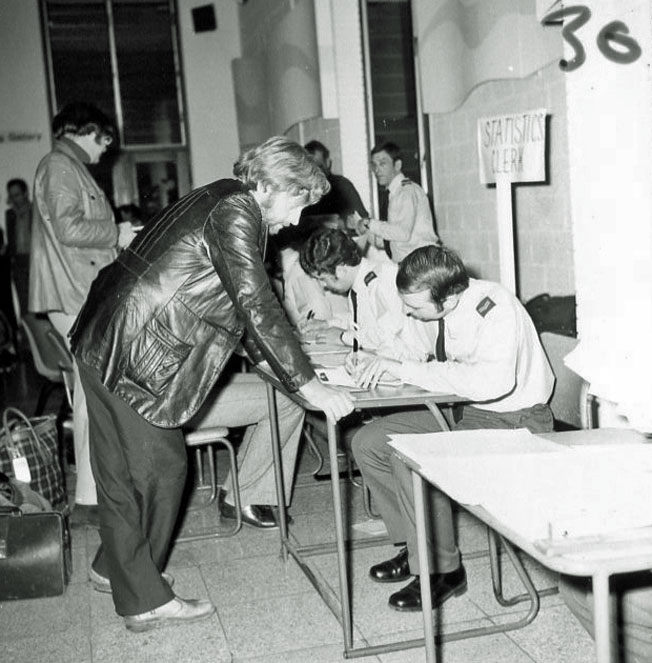

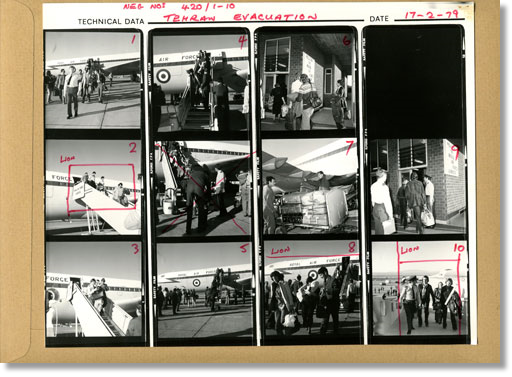

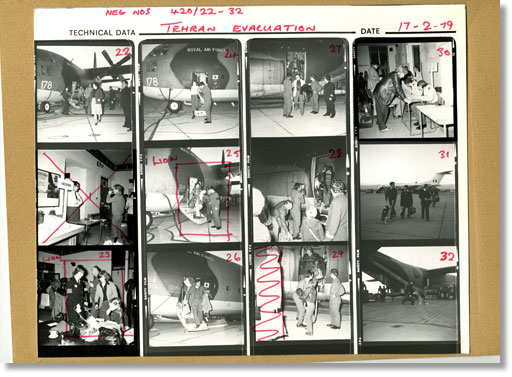

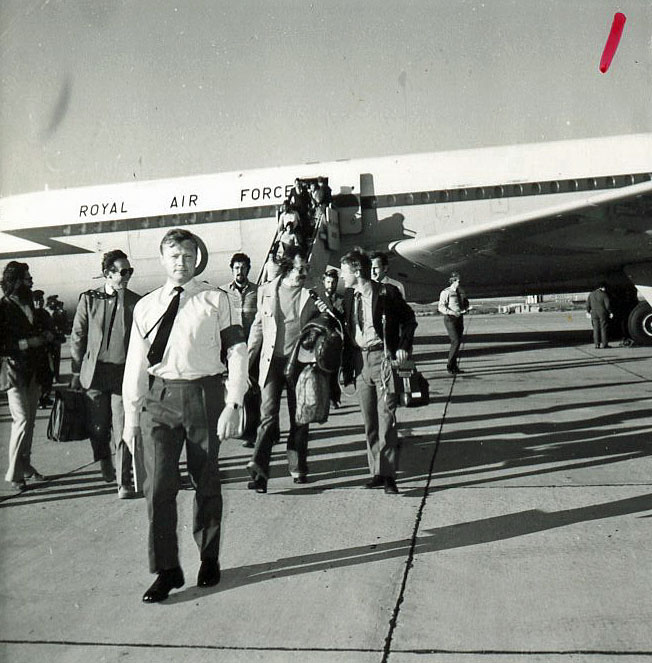

Your request for scary memories of evacuations and the like - and the fact that we are de-cluttering the house prior to going for sale and downsizing, has uncovered a set of RAF Akrotiri station photographer's proofs from the Iran Airlift of Feb 1979:

Subject: Iran Airlift 1979 - AKT Movements

Hi Tony,

Your request for scary memories of evacuations and the like - and the fact that we are de-cluttering the house prior to going for sale and downsizing, has uncovered a set of RAF Akrotiri station photographer's proofs from the Iran Airlift of Feb 1979:

The Story: With the Ayatollah Khomeini's return to Iran following the uprisings in 1978, a huge number of Westerners were stranded in the country which up to then had been ''a moderate country led by The Shah of Iran (Persia)'' - western dress, bars, night clubs etc...

There was an outcry about a rescue mission since we had handled individual aircraft from Bandar Abbas, Mashaad and Tehran, but suddenly the stakes were raised.

The Germans sent a full team of C160s and ground staff plus a Tactical Radio unit who spent nearly 3 weeks partying around Akrotiri and Cyprus but never went anywhere - the aircraft stayed on Alpha Ramp for the entire duration.

Finally, Headquarters 38 Group, as directed by MoD UK, sent a composite help team of VC10 & C130 plus a UKMAMS Team (led by Dick Leonard) to assist the Akrotiri Movers. Additionally, British Airways Air Tours positioned 3 x 707's as the plan was to pick up from Tehran (any Western nationality but primarily British), fly them to Akrotiri and British Airways would then, under a Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) contract, fly them to the UK.

Everybody at Akrotiri wanted to be involved, from the Station Commander down, plus the folks from The British Consulate in Nicosia, the Local Barclays Bank Manager, Red Cross, RAF Medics, RAF Police etc. All evacuees were interviewed, completed documentation for FCO and others to ensure the funds from other governments could be recovered. Meals were provided in the Air Terminal restaurant.

The bank officers conducted a real trade in converting Rials into Sterling and the Movers' charity box saw a massive donation one late afternoon of over 1 Million rials which was priced at approx £700 - surprise, by the time the bank could arrange the deposit to the charity account the following day the rate of exchange had dropped and we finished up with just over £300... the price of war!!

There was an outcry about a rescue mission since we had handled individual aircraft from Bandar Abbas, Mashaad and Tehran, but suddenly the stakes were raised.

The Germans sent a full team of C160s and ground staff plus a Tactical Radio unit who spent nearly 3 weeks partying around Akrotiri and Cyprus but never went anywhere - the aircraft stayed on Alpha Ramp for the entire duration.

Finally, Headquarters 38 Group, as directed by MoD UK, sent a composite help team of VC10 & C130 plus a UKMAMS Team (led by Dick Leonard) to assist the Akrotiri Movers. Additionally, British Airways Air Tours positioned 3 x 707's as the plan was to pick up from Tehran (any Western nationality but primarily British), fly them to Akrotiri and British Airways would then, under a Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) contract, fly them to the UK.

Everybody at Akrotiri wanted to be involved, from the Station Commander down, plus the folks from The British Consulate in Nicosia, the Local Barclays Bank Manager, Red Cross, RAF Medics, RAF Police etc. All evacuees were interviewed, completed documentation for FCO and others to ensure the funds from other governments could be recovered. Meals were provided in the Air Terminal restaurant.

The bank officers conducted a real trade in converting Rials into Sterling and the Movers' charity box saw a massive donation one late afternoon of over 1 Million rials which was priced at approx £700 - surprise, by the time the bank could arrange the deposit to the charity account the following day the rate of exchange had dropped and we finished up with just over £300... the price of war!!

At no stage did the existing UK-Cyprus schedules or even exercise movements stop; the Akrotiri Movers operated their normal tasks and Dick Leonard's UKMAMS troops managed the C130 ops (in the main). The outcome was a complete success for everybody and we - the Movers, were thanked profusely but importantly had a big celebration prior to Dick and his team recovering to the UK.

The most amusing story: Four young Irish ladies advised the Pax Terminal folks that their suitcases hadn't been offloaded from their C130 and wanted to claim etc. Anyway, our UK Customs (seconded to Cyprus) were suddenly interested when the suitcases were found in the terminal and insisted on opening them in the presence of the four ladies. Surprise! They contained very flimsy and provocative lingerie plus numerous self gratification devices (dildos if you must - the sizing being large!). To much embarrassment for the ladies and just about every Mover turning up to view the contents, it transpired that the ladies had been strippers/lap dancers in a Tehran night club and they were tools of the trade! Another day in the life of Movers. I'm sure some of the folks stationed there in February 1979 will be able to add more accurate information, identify faces or provide more funny stories?

The most amusing story: Four young Irish ladies advised the Pax Terminal folks that their suitcases hadn't been offloaded from their C130 and wanted to claim etc. Anyway, our UK Customs (seconded to Cyprus) were suddenly interested when the suitcases were found in the terminal and insisted on opening them in the presence of the four ladies. Surprise! They contained very flimsy and provocative lingerie plus numerous self gratification devices (dildos if you must - the sizing being large!). To much embarrassment for the ladies and just about every Mover turning up to view the contents, it transpired that the ladies had been strippers/lap dancers in a Tehran night club and they were tools of the trade! Another day in the life of Movers. I'm sure some of the folks stationed there in February 1979 will be able to add more accurate information, identify faces or provide more funny stories?

To Movers across the globe - stay safe and dodge the virus - Cheers, Ian

Refugee assisting refugee. Perhaps an unconventional idiom, but truly applicable to team members of NEAF MAMS domiciled in Limassol at the outbreak of the Cyprus war in July 1974 - and subsequently involved in what was accepted to be the largest RAF airlift since Berlin. Long remembered events – Kingsfield (glider hangar); sand and cinder runway; dust; hot sunshine, incessant aircraft movements - up to 24 sorties per day on 23rd/24th July; battalions of infantry - and return trips to Akrotiri - strapping in multi nationals on the para seats as the Hercules turned to take off - and a sprinkling of international politics of the European kind!

However, to understand the background to the Cyprus war, it is appropriate to include mention of the coup in Cyprus on Monday 15th July 1974, when Greek nationals attacked police stations and military units across Cyprus, and, in Nicosia, imposed Nikos SAMSON (an ex EOKA terrorist) as the new President of Cyprus deposing President Makarios. (At the time it was suggested that the long time president had been killed but this was proven to be bogus propaganda.) An horrendously worrying time for the families. My own wife, Rose, recalls that it was that very morning that she was showing a neighbour, the wife of a newly arrived Royal Scots soldier the direction, ‘across the bondu’ to the local NAAFI shop. En-route they stopped at a local bakery. The next thing they heard was a very loud explosion, and seconds later the outbreak of small arms firing. The Cypriot baker explaining that the radio was reporting Makarios had been killed. Desperately anxious, Rose then chose a time to hasten home, nervous for the well-being of our youngest child, Paul who was, at the time, in his Limassol kindergarten located in close proximity to the police station- the focal point of the local rebellion. Later, and with great relief, Rose witnessed the school bus finally arrive home, with all the children lying prostrate on the floor.

During that week I was ‘on task’ and deployed with members of blue team NEAF MAMS conducting the ‘Bait shuttle’ - in support of the Oman war. It was late afternoon, whilst on the ground at Salalah, that we were to learn of the coup. I recall we were sitting on the open ramp, enjoying the breeze, gazing inland towards the Jebel Massif escarpment. The navigator came down from the flight deck and reported that he had heard on the HF that there had been a coup in Cyprus - and Makarios was dead. Obviously, quite disarming news with most of us living off base in Limassol. However we returned to Masirah and then to Akrotiri, and paradoxically were ultimately allowed home - into Limassol. Once home on Friday, I was preparing for an early pick up by a colleague the next morning (Saturday 20th) for an anticipated task at Kingsfield, Dhekelia. My own car was in a local garage, due for a respray, prior to my sending it home to the UK. However, events were to take a dramatic twist.