From: David Forsyth, St Hilaire de Riez

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #093024

Hello Tony,

The article on the anniversary of the Battle of Britain prompts me to share a couple of anecdotes which you may find useful for the next newsletter.

As a newly-minted young Acting Flight Lieutenant in September 1971, I was posted to the staff of Air Marshal Sir Ivor Broom, (then still an unbe-knighted Air Vice Marshal), AOC of 11 (Fighter) Group which was effectively the scaled-down Fighter Command... We were located at RAF Bentley Priory which also provided accommodation in the Officers' Mess. Though I was not the only Flight Lieutenant, there were several be-medalled gentlemen and a smattering of ladies, I was by far the youngest.

I was told pretty much on arrival that I would have two duties related to the upcoming Battle of Britain anniversary: to attend Westminster Abbey as an Usher and to act as a close-hosting officer for a Battle of Britain pilot at the annual Cocktail Party and Reception in the Mess.

Dealing with the party first, along with a dozen or so Flight Lieutenants and Squadron Leaders, I waited from about 6pm for a briefing and then to meet the honoured guests in the entrance to the impressive and imposing Mess. I had been allocated a name which meant nothing to me and, of course, no Google in those days to help find out more. Time went on and one by one my fellow hosts met their guests and went on to join the long line to be welcomed by the AOC and his wife. Soon I was on my own. At 7 pm I gave up and headed into the Reception and, no longer having to "host", got stuck into the G & T's at a most enjoyable party. By about 9 pm, the AOC had gone and we were down into a small circle of about a dozen going for one (at least) last drink. I found myself standing beside a chap who looked to be in his fifties. Assuming he was also on the AOC's staff, I introduced myself only to hear coming back at me the name of the chap I was supposed to be hosting. When I jocularly claimed, emboldened by half a dozen G & T's, that I had waited all night for him, with a twinkle in his eye, he explained: "Laddie, I have been coming to these "dos" for years. Early on I realised that if you come in through the kitchens, you can bypass all this waiting in line to greet the AOC and get stuck into the party straight away". I learned something from that - not entirely sure what.

On a distinctly more sober note, off to Westminster Abbey to meet and escort all manner of VIPs from the great and the good to chaps who had flown in the Battle but had reverted to more "ordinary" lives after the war. The abiding memory of slow-marching in that majestic, echoing building, behind the officer carrying the giant book in which are listed the names of all the pilots lost during the Battle of Britain.

A stark contrast to the previous evening's shenanigans.

As Aye

David

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #093024

Hello Tony,

The article on the anniversary of the Battle of Britain prompts me to share a couple of anecdotes which you may find useful for the next newsletter.

As a newly-minted young Acting Flight Lieutenant in September 1971, I was posted to the staff of Air Marshal Sir Ivor Broom, (then still an unbe-knighted Air Vice Marshal), AOC of 11 (Fighter) Group which was effectively the scaled-down Fighter Command... We were located at RAF Bentley Priory which also provided accommodation in the Officers' Mess. Though I was not the only Flight Lieutenant, there were several be-medalled gentlemen and a smattering of ladies, I was by far the youngest.

I was told pretty much on arrival that I would have two duties related to the upcoming Battle of Britain anniversary: to attend Westminster Abbey as an Usher and to act as a close-hosting officer for a Battle of Britain pilot at the annual Cocktail Party and Reception in the Mess.

Dealing with the party first, along with a dozen or so Flight Lieutenants and Squadron Leaders, I waited from about 6pm for a briefing and then to meet the honoured guests in the entrance to the impressive and imposing Mess. I had been allocated a name which meant nothing to me and, of course, no Google in those days to help find out more. Time went on and one by one my fellow hosts met their guests and went on to join the long line to be welcomed by the AOC and his wife. Soon I was on my own. At 7 pm I gave up and headed into the Reception and, no longer having to "host", got stuck into the G & T's at a most enjoyable party. By about 9 pm, the AOC had gone and we were down into a small circle of about a dozen going for one (at least) last drink. I found myself standing beside a chap who looked to be in his fifties. Assuming he was also on the AOC's staff, I introduced myself only to hear coming back at me the name of the chap I was supposed to be hosting. When I jocularly claimed, emboldened by half a dozen G & T's, that I had waited all night for him, with a twinkle in his eye, he explained: "Laddie, I have been coming to these "dos" for years. Early on I realised that if you come in through the kitchens, you can bypass all this waiting in line to greet the AOC and get stuck into the party straight away". I learned something from that - not entirely sure what.

On a distinctly more sober note, off to Westminster Abbey to meet and escort all manner of VIPs from the great and the good to chaps who had flown in the Battle but had reverted to more "ordinary" lives after the war. The abiding memory of slow-marching in that majestic, echoing building, behind the officer carrying the giant book in which are listed the names of all the pilots lost during the Battle of Britain.

A stark contrast to the previous evening's shenanigans.

As Aye

David

How the military stages a civilian evacuation from a dangerous or unstable country

When British nationals need to be evacuated from hotspots worldwide, British military personnel are often called upon to help. British troops in Cyprus are currently preparing for a potential evacuation of Lebanon as tensions in the Middle East continue to escalate. These Non-Combatant Evacuation Operations, or NEOs as they are known, are something the UK Armed Forces train for. But an NEO is a complex process, so how do they work?

The decision to evacuate a country is made by the Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO) in London. In order for the military to become involved, the Foreign Secretary makes a formal request to the Defence Secretary for assistance, with the Chief of the Defence Staff then appointing the overall NEO commanders. From here, the Joint Commander, usually the Chief of Joint Operations, runs the mission from Permanent Joint Headquarters at Northwood in northwest London.

The decision to evacuate a country is made by the Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO) in London. In order for the military to become involved, the Foreign Secretary makes a formal request to the Defence Secretary for assistance, with the Chief of the Defence Staff then appointing the overall NEO commanders. From here, the Joint Commander, usually the Chief of Joint Operations, runs the mission from Permanent Joint Headquarters at Northwood in northwest London.

British nationals being evacuated out of Sudan on board an RAF Atlas A400M

They are responsible for deploying and sustaining forces during an evacuation, as well as bringing them home safely. "There will be people who, on very short notice, stand by to execute this sort of operation," said retired Colonel Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a former NEO planner. "There will be contingency plans, there will be plans to do these types of operations all over the place. These would've been recced, rehearsed, by Foreign Office and military planners who will identify suitable airfields and suitable ports. The other key thing that the Foreign Office and the MOD (Ministry of Defence) will be looking at is intelligence that's being gathered – so exactly what the situation is on the ground. It might well be that there is fighting in one part of the country which would preclude some airfields there, therefore the Foreign Office and the MOD will choose other airfields and ports to use," he added.

The UK has carried out a number of Non-Combatant Evacuation Operations, most recently in South Sudan. In 2023, the UK completed the largest and longest Western evacuation from the east African country. This saw 2,450 people evacuated on 30 flights, with the evacuation supported by the RAF.

In 2006, the UK military evacuated 4,000 Britons from Beirut after war broke out between Israel and Hezbollah.

Five years later, the RAF and UK Special Forces flew oil workers out of the Libyan desert after the country erupted into a violent revolution.

Additionally, HMS Cumberland ferried hundreds of UK nationals from Benghazi to safety in Malta.

But it was the evacuation of Afghanistan – codenamed Operation Pitting – that showed most clearly the complexity and dangers of organising an NEO.

In 2006, the UK military evacuated 4,000 Britons from Beirut after war broke out between Israel and Hezbollah.

Five years later, the RAF and UK Special Forces flew oil workers out of the Libyan desert after the country erupted into a violent revolution.

Additionally, HMS Cumberland ferried hundreds of UK nationals from Benghazi to safety in Malta.

But it was the evacuation of Afghanistan – codenamed Operation Pitting – that showed most clearly the complexity and dangers of organising an NEO.

With the Taliban closing in on the Afghan capital of Kabul, 1,000 personnel deployed to the city's airport to help extract 15,000 individuals in two weeks.

It was the largest humanitarian aid operation since the Berlin Airlift in 1948.

forcesnews.com

It was the largest humanitarian aid operation since the Berlin Airlift in 1948.

forcesnews.com

From: Dave Green, Huntingdon, Cambs

To: Mark Attrill, Tallinn, Estonia

Cc: Tony Gale, Gatineau, QC, Canada

Subject: Belize and the Harrier Force

Hi Mark,

It's been an awful long time since we last met, but it's always nice to read your OBB inputs. On the matter of Harriers to Belize and the 50th Anniversary, I trust the attached photos will be of value. I presume you did a Belize tour so hopefully we are talking the same language. I was in Belize from Jan - Sep 1983 as OC Movs and Stockholding working for John Bell.

To: Mark Attrill, Tallinn, Estonia

Cc: Tony Gale, Gatineau, QC, Canada

Subject: Belize and the Harrier Force

Hi Mark,

It's been an awful long time since we last met, but it's always nice to read your OBB inputs. On the matter of Harriers to Belize and the 50th Anniversary, I trust the attached photos will be of value. I presume you did a Belize tour so hopefully we are talking the same language. I was in Belize from Jan - Sep 1983 as OC Movs and Stockholding working for John Bell.

The Orange Walk ranges were on land normally occupied by cattle, so these 2 pics were taken of a Harrier doing SNEB rocket attacks on the range viewed from a teenie-weenie Gazelle trip I did. Great fun clearing the range of animals by low flying to scare them off before the range was used.

We did Harrier and Puma frame changes by Herc whilst I was out there hence the Harrier being loaded, I seem to recall this was a lot easier than the Puma move.

The Charlie/Delta Hide pic (at left) is an official RAF pic taken by the on-base photographer and the Golf Hide pic isn't mine but I found it online.

The Puma and Harrier pics at Williamson hangar were taken way before my time out there and are from a sheet of RAF contact prints I found in my draw in the Movs office. The Harrier appears to have 1 Sqn badging so this must have been the initial or early second deployments of the Harriers.

The Zippo is obviously self explanatory. I thought this was lost after several RAF moves but I recently found it in a box in the loft!

I have quite a few other images of Belize including Airport Camp, Rideau, Salamanca etc., and refuelling vehicles and fuel tankage if you need any background pics. I also have a few other Harrier pics from the 1980s from different locations. Please let me know if any of this might be of use to you and I can send some on.

Hope all is well in Tallinn

Rgds

Dave Green

Hope all is well in Tallinn

Rgds

Dave Green

Royal Australian Air Force Orders 470 Exosuits

470 exosuits were purchased by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and will be gradually implemented for those who need them. The Apex 2 by HeroWear was tested by 23 Squadron at RAAF Base Amberley. This is the largest single order for military exoskeletons. The suits are envisioned to help with logistical tasks.

Squadron Leader Jessica Sutherland of 23 Squadron, responsible for air and ground movements, said, “My teams are building pallets, lifting passenger bags, and regularly twisting their bodies to manipulate cargo, which puts a significant strain on their bodies.”

“‘There are situations with no manual handling equipment," Sean Lacey, of the Combat Support Group said. "This can include disaster relief, such as in flood-hit regions where the RAAF assists around the world.”

The above is the single-most-important concept about military or occupational exoskeletons. No one is trying to make people work harder or replace existing tools and equipment. However, some situations exist today and will continue to exist for decades to come at the current rate of automation, where people have to get directly involved. That is, where exoskeletons will always have a potential use (if they are a good fit for the task).The goal isn’t to create superhumans or substitute strength or endurance training. In collaboration with HeroWear, a train-the-trainer program was designed to use the exosuits appropriately and safely.

exoskeletonreport.com

Squadron Leader Jessica Sutherland of 23 Squadron, responsible for air and ground movements, said, “My teams are building pallets, lifting passenger bags, and regularly twisting their bodies to manipulate cargo, which puts a significant strain on their bodies.”

“‘There are situations with no manual handling equipment," Sean Lacey, of the Combat Support Group said. "This can include disaster relief, such as in flood-hit regions where the RAAF assists around the world.”

The above is the single-most-important concept about military or occupational exoskeletons. No one is trying to make people work harder or replace existing tools and equipment. However, some situations exist today and will continue to exist for decades to come at the current rate of automation, where people have to get directly involved. That is, where exoskeletons will always have a potential use (if they are a good fit for the task).The goal isn’t to create superhumans or substitute strength or endurance training. In collaboration with HeroWear, a train-the-trainer program was designed to use the exosuits appropriately and safely.

exoskeletonreport.com

From: David Powell, Princes Risborough, Bucks

Subject: Cancelled Operations

Hello Tony,

Can’t let the Cancelled Ops challenge go by without revisiting my Far East experience for new readers, see OBB 042916, and a claim for the longest delayed flight home.

This was when the RAF Airlift for the closure of the RAF Gong Kedak in June 1966 was cancelled. This change in plans was to leave the unit, now in the hands of the closure team detached from Singapore, open for 14 Sqn RNZAF Canberras while their hard-standing at RAF Tengah was refurbished. After a couple more weeks, they went home and we started to wrap up the mainly tented camp. Resupply was food from Butterworth courtesy of RAAF Dakotas, and film and odds and ends from Changi by a weekly RNZAF Bristol Freighter. Closure basically done in another couple of weeks, and we waited to be given the details of the deferred RAF Beverley and Argosy airlift back south.

No rush, the few of us left settled into a relatively relaxed C&M mornings only routine. Afternoons were usually spent on one of the nearby deserted islands. And, we waited. It was only in August, when wondering what had happened to my kit and car back at Changi, that I sent a telegram to HQ224 Group, asking if there was any chance of our presumed airlift, and by the way there was a train load of tents heading your way. Two days - silence. After a hastener, a Pembroke arrived and staff officers ran around with clip boards. The following week, the planned airlift reappeared and we finally closed. Apparently, the pin had been pulled out of the map in HQFEAF when we were originally planned to close, and because RAF Gong Kedak only involved NZ and Australian aircraft, nobody of importance noticed we were still there up by the Thai border until my telegram! I wonder how much longer we would have stayed there if I hadn’t sent it?

Stay safe, have fun!

David Powell UK MAMS F Team 1967-69.

Subject: Cancelled Operations

Hello Tony,

Can’t let the Cancelled Ops challenge go by without revisiting my Far East experience for new readers, see OBB 042916, and a claim for the longest delayed flight home.

This was when the RAF Airlift for the closure of the RAF Gong Kedak in June 1966 was cancelled. This change in plans was to leave the unit, now in the hands of the closure team detached from Singapore, open for 14 Sqn RNZAF Canberras while their hard-standing at RAF Tengah was refurbished. After a couple more weeks, they went home and we started to wrap up the mainly tented camp. Resupply was food from Butterworth courtesy of RAAF Dakotas, and film and odds and ends from Changi by a weekly RNZAF Bristol Freighter. Closure basically done in another couple of weeks, and we waited to be given the details of the deferred RAF Beverley and Argosy airlift back south.

No rush, the few of us left settled into a relatively relaxed C&M mornings only routine. Afternoons were usually spent on one of the nearby deserted islands. And, we waited. It was only in August, when wondering what had happened to my kit and car back at Changi, that I sent a telegram to HQ224 Group, asking if there was any chance of our presumed airlift, and by the way there was a train load of tents heading your way. Two days - silence. After a hastener, a Pembroke arrived and staff officers ran around with clip boards. The following week, the planned airlift reappeared and we finally closed. Apparently, the pin had been pulled out of the map in HQFEAF when we were originally planned to close, and because RAF Gong Kedak only involved NZ and Australian aircraft, nobody of importance noticed we were still there up by the Thai border until my telegram! I wonder how much longer we would have stayed there if I hadn’t sent it?

Stay safe, have fun!

David Powell UK MAMS F Team 1967-69.

Deployment of ADF Personnel and Aircraft to the Middle East

Australian High Commissioner to the Republic of Cyprus, Fiona McKergow, assists a woman and her family to board a bus after arriving in Larnaca, Cyprus, by Australian government chartered aircraft from Beirut, Lebanon.

ADF personnel and aircraft have been deployed to the Middle East as part of Operation Beech – Defence’s support of the Australian government’s response to the Middle East conflict.

Australian Army and Royal Australian Air Force personnel, alongside RAAF C-130J aircraft, have deployed to the region in a non-combat role. The deployment of Australian aircraft and supporting Defence personnel is a precautionary measure to support whole-of-Australian-government contingency planning and delivery of support to Australian citizens and approved foreign nationals in the region, if required.

An official Defence statement released today, 6th October, says the ADF contingent will provide the Australian government the additional capabilities to assist Australian citizens and approved foreign nationals should the security situation deteriorate in the region.

contactairlandandsea.com

Australian Army and Royal Australian Air Force personnel, alongside RAAF C-130J aircraft, have deployed to the region in a non-combat role. The deployment of Australian aircraft and supporting Defence personnel is a precautionary measure to support whole-of-Australian-government contingency planning and delivery of support to Australian citizens and approved foreign nationals in the region, if required.

An official Defence statement released today, 6th October, says the ADF contingent will provide the Australian government the additional capabilities to assist Australian citizens and approved foreign nationals should the security situation deteriorate in the region.

contactairlandandsea.com

From: Andy Spinks, Warkleigh, Devon

Subject: C-17 Evacuation Ops - Assessing the Risk

Hi Tony,

I am forwarding this article as it is fairly short while being very interesting (IMHO). The movers don’t get a mention and may not have been on board anyway. But it is an interesting tale nevertheless.

Regards to all

Andy

Subject: C-17 Evacuation Ops - Assessing the Risk

Hi Tony,

I am forwarding this article as it is fairly short while being very interesting (IMHO). The movers don’t get a mention and may not have been on board anyway. But it is an interesting tale nevertheless.

Regards to all

Andy

C-17 Evacuation Ops - Assessing the Risk

With the advantage of having time on their hands, an RAF C-17 team was able to thoroughly evaluate the risk associated with an emergency mission and successfully evacuate almost 200 people from South Sudan. AM Sean Reynolds CB CBE DFC discusses the risk mitigation behind a successful flight.

“May the holes in your Swiss cheese never line up”. Those were the words expressed very eloquently by a senior test pilot during his leaving speech from the RAF after more than 30 years of distinguished service. This caused a knowing chuckle from the audience of aviator friends that had assembled to say thank you and farewell. But what did he mean? Clearly this was not some advice to be taken and followed up on our next visit to the deli counter in Sainsburys.

“May the holes in your Swiss cheese never line up”. Those were the words expressed very eloquently by a senior test pilot during his leaving speech from the RAF after more than 30 years of distinguished service. This caused a knowing chuckle from the audience of aviator friends that had assembled to say thank you and farewell. But what did he mean? Clearly this was not some advice to be taken and followed up on our next visit to the deli counter in Sainsburys.

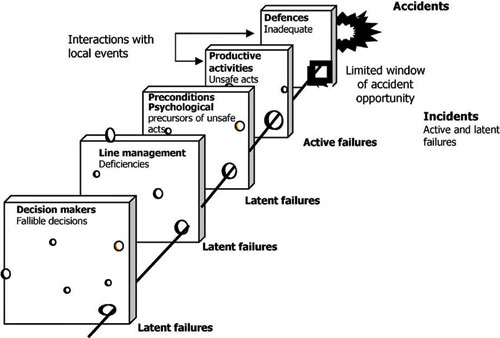

Swiss Cheese

At Left: A diagram .to illustrate the Swiss Cheese model.

I am guessing that many of those reading this will have come across Professor James Reason’s model of the Swiss cheese of accident causation, which is used in risk analysis and risk management with the principle being layered defences.

The model likens human systems to multiple slices of Swiss cheese, which have randomly placed and sized holes in each slice, stacked side by side. The risk of a threat becoming a reality is mitigated by the differing layers and types of defences which are ‘stacked’ behind each other.

Therefore, in theory, lapses and weaknesses in one defence do not allow a risk to materialise (e.g a hole in each slice in the stack aligning with holes in all the other slices of cheese) to prevent a single point of failure.

I am guessing that many of those reading this will have come across Professor James Reason’s model of the Swiss cheese of accident causation, which is used in risk analysis and risk management with the principle being layered defences.

The model likens human systems to multiple slices of Swiss cheese, which have randomly placed and sized holes in each slice, stacked side by side. The risk of a threat becoming a reality is mitigated by the differing layers and types of defences which are ‘stacked’ behind each other.

Therefore, in theory, lapses and weaknesses in one defence do not allow a risk to materialise (e.g a hole in each slice in the stack aligning with holes in all the other slices of cheese) to prevent a single point of failure.

Layered Defences

On 18 December 2013, a deteriorating security situation in South Sudan led to the evacuation of British Nationals and other Entitled Persons by an RAF Boeing C-17 Globemaster.

Much of what we do in aviation, and other safety critical activities, has these layered defences built into it. As technology has evolved the way we do business, and increased efficiency and safety, it has also increased complexity of the processes. Consequently, safety dependence has shifted from the knowledge and competence of the individual to safe systems of work.

The use of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and checklists are prime examples of this. However, the human is still at the centre of these processes and is often the last line of defence that can block the holes in the cheese; something that I was to find out first hand just before Christmas in 2013.

On 18 December 2013, a deteriorating security situation in South Sudan led to the evacuation of British Nationals and other Entitled Persons by an RAF Boeing C-17 Globemaster.

Much of what we do in aviation, and other safety critical activities, has these layered defences built into it. As technology has evolved the way we do business, and increased efficiency and safety, it has also increased complexity of the processes. Consequently, safety dependence has shifted from the knowledge and competence of the individual to safe systems of work.

The use of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and checklists are prime examples of this. However, the human is still at the centre of these processes and is often the last line of defence that can block the holes in the cheese; something that I was to find out first hand just before Christmas in 2013.

At the time, I was in command of the RAF’s No 2 Group. This was one of the two front-line groups in the RAF and comprised of the Air Mobility Force, Search and Rescue Force and Force Protection Force (RAF Regiment and RAF Police). I also had safety responsibility for Boscombe Down and the Empire Test Pilot School. The RAF had recently undergone a transformation in the way that it managed safety with the advent of the Military Aviation Authority (MAA) and following the cathartic lessons that had been learnt from the loss of a Nimrod over Afghanistan in 2006.

As a group commander, I was appointed as the Operational Duty Holder for all safety aspects and decisions and held legally accountable and responsible for them by the Secretary of State for Defence. I received a personal letter from him on appointment telling me this which was both unsettling and empowering in equal measure.

So, having been in post for almost a year, I had a good feel for the organisation and was comfortable with the operational risks that I was carrying. As a helicopter pilot, albeit with a lapsed fixed wing CPL, I had deliberately focused on the areas that I was less familiar with and reckoned that safety management took up about 30% of my working week. I had received some excellent training and mentoring from the MAA and had a very good ops and safety team to support me, which was just as well during a challenging 24-hour period.

As a group commander, I was appointed as the Operational Duty Holder for all safety aspects and decisions and held legally accountable and responsible for them by the Secretary of State for Defence. I received a personal letter from him on appointment telling me this which was both unsettling and empowering in equal measure.

So, having been in post for almost a year, I had a good feel for the organisation and was comfortable with the operational risks that I was carrying. As a helicopter pilot, albeit with a lapsed fixed wing CPL, I had deliberately focused on the areas that I was less familiar with and reckoned that safety management took up about 30% of my working week. I had received some excellent training and mentoring from the MAA and had a very good ops and safety team to support me, which was just as well during a challenging 24-hour period.

On 18 December 2013, most of the world seemed to be enjoying the run up to Christmas. However, despite a relentless demand for support to operations in Afghanistan, we had been closely monitoring a deteriorating security situation in South Sudan and had planned for a contingency operation to evacuate British Nationals and other Entitled Persons (EPs) by using an RAF Boeing C-17 Globemaster strategic transport aircraft.

Having been figuratively ‘on and off the bus’ for several days, on the evening of 17 December the Operations Directorate in the Ministry of Defence told us to execute the mission. The aircraft departed for the South Sudanese capital, Juba, with a heavy crew (3 pilots and 2 loadmasters) plus a security party of RAF Regiment and RAF Police to provide force protection while it was on the ground. It also had a team from the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) to process the EPs and ensure that we were only evacuating those who were entitled.

During the planning process we had tried to identify most of the operational risks and then put mitigations in place. We even formed a ’Red Team’ to try and pick apart the plan and identify the known risks, but we knew that the main tactical risk – which was the deteriorating security situation around Juba – was to be mitigated by the element of surprise and by the fact that that we would arrive at first light.

Having been figuratively ‘on and off the bus’ for several days, on the evening of 17 December the Operations Directorate in the Ministry of Defence told us to execute the mission. The aircraft departed for the South Sudanese capital, Juba, with a heavy crew (3 pilots and 2 loadmasters) plus a security party of RAF Regiment and RAF Police to provide force protection while it was on the ground. It also had a team from the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) to process the EPs and ensure that we were only evacuating those who were entitled.

During the planning process we had tried to identify most of the operational risks and then put mitigations in place. We even formed a ’Red Team’ to try and pick apart the plan and identify the known risks, but we knew that the main tactical risk – which was the deteriorating security situation around Juba – was to be mitigated by the element of surprise and by the fact that that we would arrive at first light.

Evacuation Mission

A Need to Know

This is known as operational security (OPSEC) with only those who really needed to know being aware. Other risk mitigations were the heavy crew to manage fatigue, because once the aircraft departed Juba it would proceed to Entebbe in Uganda – which would potentially mean a 20 hour working day for the crew.

Other mitigations were crew qualifications. The crew were qualified to fly on Night Vision Goggles (NVGs), as it would be a first light arrival, and they were all specially selected for this flight in terms of ability and experience.

We also carried the security party for the hour that the aircraft would be on the ground and a team from the British Embassy, including the Defence Attache (DA), who would be at the airport to smooth any local difficulties that might arise. Finally, the weather for the next 48 hours in that part of Central Africa looked good.

So, you can therefore imagine my exasperation when, about two hours after the aircraft departed, I got a call from my intelligence team alerting me to a Tweet that had been posted by the FCO telling the world that a RAF transport aircraft was on its way to Juba to evacuate our Eps!

Our OPSEC was now, in my view, potentially compromised. My immediate inclination, apart from some expletives about ‘eagles and turkeys’, was to turn the aircraft around. However, after some discussions with various stakeholders, we decided to let the aircraft continue and monitor the situation through the night to see if it looked likely that the ‘bad guys’ had picked up on the Tweet.

I set a decision point of an hour before the top of descent and challenged my intelligence team to give me an all-source assessment on a go-no go decision. I also decided not to inform the crew at this point as I didn’t want them unnecessarily distracted from the task in hand. The first holes in the cheese had tried to line up.

Our OPSEC was now, in my view, potentially compromised. My immediate inclination, apart from some expletives about ‘eagles and turkeys’, was to turn the aircraft around. However, after some discussions with various stakeholders, we decided to let the aircraft continue and monitor the situation through the night to see if it looked likely that the ‘bad guys’ had picked up on the Tweet.

I set a decision point of an hour before the top of descent and challenged my intelligence team to give me an all-source assessment on a go-no go decision. I also decided not to inform the crew at this point as I didn’t want them unnecessarily distracted from the task in hand. The first holes in the cheese had tried to line up.

Situational Awareness

An hour before descent I got the relevant members of my Command Group together to do the final estimate on whether to proceed. It was during this meeting that the cheese started to melt. Just as we were about to give the go ahead, we were informed that the runway at Juba airport was now blocked by an Oman Air Boeing 737 that had suffered a nose-wheel collapse during the landing roll and was now stuck halfway down the runway. On the face of it this was a mission abort scenario – however, this is where training and experience kicked in.

In critical decision-making, time is normally the dominant factor in limiting the potential choices and options. On this occasion we had time. The aircraft was carrying at least two hours of holding fuel so we had time to try and gain as much situational awareness as possible. I gave my operations team an hour to get me as much information as possible by getting hold of any imagery we could plus an assessment from the DA and anyone else who could give us an accurate picture of what was happening. We also decided to use our Satellite Communications system to inform the captain of the developing situation and to tell him that he might have to hold or divert.

In critical decision-making, time is normally the dominant factor in limiting the potential choices and options. On this occasion we had time. The aircraft was carrying at least two hours of holding fuel so we had time to try and gain as much situational awareness as possible. I gave my operations team an hour to get me as much information as possible by getting hold of any imagery we could plus an assessment from the DA and anyone else who could give us an accurate picture of what was happening. We also decided to use our Satellite Communications system to inform the captain of the developing situation and to tell him that he might have to hold or divert.

The emerging picture, accurately depicted on the satellite imagery I was looking at, was of a runway that was blocked about two thirds of the way down with a little over 5,000ft available. We also did not know whether there was any damage to the runway, or any debris left from the stricken 737.

Two months beforehand I had completed a weeklong course on the C-17, that was designed to give me an understanding of the capabilities and challenges of operating this very capable aircraft. This course was a mix of ground school, simulator and live flying including three hours of base training at RAF Brize Norton. This culminated in a demonstration of an assault landing technique where the aircraft was landed and stopped at close to max landing weight in less than 3,000ft.

Two months beforehand I had completed a weeklong course on the C-17, that was designed to give me an understanding of the capabilities and challenges of operating this very capable aircraft. This course was a mix of ground school, simulator and live flying including three hours of base training at RAF Brize Norton. This culminated in a demonstration of an assault landing technique where the aircraft was landed and stopped at close to max landing weight in less than 3,000ft.

Questions of Risk

Armed with this knowledge, I asked my Senior Operator whether we could still use the available runway to land and then depart from. The answer was ‘yes’ but that we would be breaking most of my regulations in terms of landing on a blocked runway. This is when a disciplined approach to operational risk management is needed. The natural inclination, with a pressing operational imperative, is to just do it. However, we had time so I asked my team to sentence the risk. In so doing we needed to answer four key questions: What is the risk? What is the benefit of taking the risk? Can we tolerate the risk if it occurs? What can we do to drive the risk to an ALARP (as low as reasonably practical) position?

The risk to the aircraft and crew was low. We could have a brake failure or thrust reverser lockout – which are almost unheard of on the C-17 – but the aircraft was more than capable of stopping and departing in the space available. The benefit was evacuating at least 100 people from a potentially life-threatening situation which was deteriorating by the hour. Therefore, the risk and benefits were easily quantifiable and made the risk worth carrying.

Armed with this knowledge, I asked my Senior Operator whether we could still use the available runway to land and then depart from. The answer was ‘yes’ but that we would be breaking most of my regulations in terms of landing on a blocked runway. This is when a disciplined approach to operational risk management is needed. The natural inclination, with a pressing operational imperative, is to just do it. However, we had time so I asked my team to sentence the risk. In so doing we needed to answer four key questions: What is the risk? What is the benefit of taking the risk? Can we tolerate the risk if it occurs? What can we do to drive the risk to an ALARP (as low as reasonably practical) position?

The risk to the aircraft and crew was low. We could have a brake failure or thrust reverser lockout – which are almost unheard of on the C-17 – but the aircraft was more than capable of stopping and departing in the space available. The benefit was evacuating at least 100 people from a potentially life-threatening situation which was deteriorating by the hour. Therefore, the risk and benefits were easily quantifiable and made the risk worth carrying.

Could I tolerate and live with the risk if the aircraft was damaged? Yes, we had the security party plus people on the ground.

Finally, what else could we do to drive the risk down? By this point the aircraft captain was fully involved in the conversation and he suggested dumping his diversion fuel for Nairobi. Entebbe had six runways and the weather was forecast to remain good. This would reduce the weight of his aircraft and allow it better stopping performance. We also tasked the DA to do a runway inspection and clear any debris that might damage the aircraft. Having sentenced the risk, we quickly wrote it down and re-read it. Finally, having reviewed the impact of the Tweet, which seemed to have been mitigated by the fact that the runway ‘appeared’ to be out of use, I gave the go-ahead for the landing.

Finally, what else could we do to drive the risk down? By this point the aircraft captain was fully involved in the conversation and he suggested dumping his diversion fuel for Nairobi. Entebbe had six runways and the weather was forecast to remain good. This would reduce the weight of his aircraft and allow it better stopping performance. We also tasked the DA to do a runway inspection and clear any debris that might damage the aircraft. Having sentenced the risk, we quickly wrote it down and re-read it. Finally, having reviewed the impact of the Tweet, which seemed to have been mitigated by the fact that the runway ‘appeared’ to be out of use, I gave the go-ahead for the landing.

The End Result

In summary, the operation proceeded to run on rails. We evacuated almost 200 people to Entebbe and the crew, quite rightly, were recognised with several awards including the Air Force Cross for the Captain.

In all of this, during a highly dynamic and unusual situation, we used as many defences as we could to prevent the holes in the cheese from lining up. We started with a robust and carefully thought through plan but when external factors started to try and line up the holes in the cheese, we used a well practiced decision and risk mitigation process to keep trying to put the defences back in place.

We used every source of information we could find from imagery to human intelligence to build our situational awareness and inform the decision making. We had a diverse set of stakeholders, from the operations and safety teams to the crew itself, to be part of that decision making and avoid ‘group think’. They were what we term SQEP. Suitably Qualified and Experienced People. Critically, if we had time then we used it to conduct rigorous analysis of all of the factors we could think of. Finally, though, once we had done this we used Mission Command to empower a highly trained crew and team to do their job.

In all of this, during a highly dynamic and unusual situation, we used as many defences as we could to prevent the holes in the cheese from lining up. We started with a robust and carefully thought through plan but when external factors started to try and line up the holes in the cheese, we used a well practiced decision and risk mitigation process to keep trying to put the defences back in place.

We used every source of information we could find from imagery to human intelligence to build our situational awareness and inform the decision making. We had a diverse set of stakeholders, from the operations and safety teams to the crew itself, to be part of that decision making and avoid ‘group think’. They were what we term SQEP. Suitably Qualified and Experienced People. Critically, if we had time then we used it to conduct rigorous analysis of all of the factors we could think of. Finally, though, once we had done this we used Mission Command to empower a highly trained crew and team to do their job.

AM Sean Reynolds CB CBE DFC

4 October 2024

4 October 2024

From: Clive Price, Brecon

Subject: Non jobs.

Hi Tony,

1969 - It was the Labour Day weekend and we were supposed to be recovering ground equipment from the International Air Show in Toronto. We had flown in a Britannia from Lyneham to Goose Bay and were scheduled to fly from there to Toronto. Because of all the visiting air show aircraft, there was no room for us in Toronto. So, a hurried revised (training?) schedule was created; we went from Goose Bay to Chicago for refuelling and then down to San Francisco for a very memorable weekend.

We stayed at the San Franciscan Hotel on Market Street which was very plush indeed; they washed all of the coins to give back as change to their guests (this was in the days when actual money was the main instrument in buying and selling). We visited Fisherman’s Wharf where we could see Alcatraz Prison (the island) and the Golden Gate Bridge. We stood on the corner of Haight and Ashbury Streets which was the centre of the Flower Power generation – took a street trolley down the very hilly road – and visited a night club where the scantily dressed disco dancers were in cages hanging from the ceiling! I can remember the song playing in my head, “If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair,” (recorded by Scott McKenzie in 1967). On the Monday (September 1st) we watched the Labour Day Parade from our hotel room windows.

We left ‘Frisco for Toronto where we stayed at the Skyline Hotel next to the airport which featured Diamond Lil’s bar – absolutely fabulous. We eventually loaded all of the ground equipment onto two Britannia’s and then returned to Lyneham via Goose Bay and Marham.

Cheers!

Taff Price

F Team

Subject: Non jobs.

Hi Tony,

1969 - It was the Labour Day weekend and we were supposed to be recovering ground equipment from the International Air Show in Toronto. We had flown in a Britannia from Lyneham to Goose Bay and were scheduled to fly from there to Toronto. Because of all the visiting air show aircraft, there was no room for us in Toronto. So, a hurried revised (training?) schedule was created; we went from Goose Bay to Chicago for refuelling and then down to San Francisco for a very memorable weekend.

We stayed at the San Franciscan Hotel on Market Street which was very plush indeed; they washed all of the coins to give back as change to their guests (this was in the days when actual money was the main instrument in buying and selling). We visited Fisherman’s Wharf where we could see Alcatraz Prison (the island) and the Golden Gate Bridge. We stood on the corner of Haight and Ashbury Streets which was the centre of the Flower Power generation – took a street trolley down the very hilly road – and visited a night club where the scantily dressed disco dancers were in cages hanging from the ceiling! I can remember the song playing in my head, “If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair,” (recorded by Scott McKenzie in 1967). On the Monday (September 1st) we watched the Labour Day Parade from our hotel room windows.

We left ‘Frisco for Toronto where we stayed at the Skyline Hotel next to the airport which featured Diamond Lil’s bar – absolutely fabulous. We eventually loaded all of the ground equipment onto two Britannia’s and then returned to Lyneham via Goose Bay and Marham.

Cheers!

Taff Price

F Team

Royal Air Force delivers vital food and medical supplies to Lebanese Armed Forces

25 October 2024 - The UK has successfully delivered more than 12,500 ration packs and 79 battlefield medical kits to the Lebanese Armed Forces. This package of medical supplies and provisions, delivered by the RAF, is funded by the UK’s Integrated Security Fund and will help support the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF).

The Lebanese Armed Forces are essential to the future security and stability of Lebanon and the wider region as the only legitimate military force of the Lebanese state.

For more than a decade, the UK has given critical support to the LAF as a trusted partner, through training, mentoring and the provision of equipment. Since 2009, the UK has trained over 34,000 LAF personnel and dedicated over £106 million in funding The UK has also helped to construct nearly 80 Border Observation posts and Forward Operating Bases as part of efforts to support Lebanese border security.

The Prime Minister, Foreign Secretary, and Defence Secretary continue to call for an immediate ceasefire and increase in humanitarian aid in both Lebanon and Gaza to allow space for a political solution. The FCDO advises all British nationals should leave Lebanon immediately and have arranged several charter flights from Lebanon in recent weeks to support this.

Defence Secretary, John Healey said: "Today’s delivery of supplies from the RAF is in direct response to a request from the Lebanese Armed Forces. The UK has supported the LAF for more than a decade, as the sole legitimate force of the Lebanese state. Our support for the LAF can help build the foundations for a stable Lebanon, as part of our wider efforts towards de-escalation and peace in the region. We continue to work closely with our partners and allies in calling for an immediate ceasefire."

The Lebanese Armed Forces are essential to the future security and stability of Lebanon and the wider region as the only legitimate military force of the Lebanese state.

For more than a decade, the UK has given critical support to the LAF as a trusted partner, through training, mentoring and the provision of equipment. Since 2009, the UK has trained over 34,000 LAF personnel and dedicated over £106 million in funding The UK has also helped to construct nearly 80 Border Observation posts and Forward Operating Bases as part of efforts to support Lebanese border security.

The Prime Minister, Foreign Secretary, and Defence Secretary continue to call for an immediate ceasefire and increase in humanitarian aid in both Lebanon and Gaza to allow space for a political solution. The FCDO advises all British nationals should leave Lebanon immediately and have arranged several charter flights from Lebanon in recent weeks to support this.

Defence Secretary, John Healey said: "Today’s delivery of supplies from the RAF is in direct response to a request from the Lebanese Armed Forces. The UK has supported the LAF for more than a decade, as the sole legitimate force of the Lebanese state. Our support for the LAF can help build the foundations for a stable Lebanon, as part of our wider efforts towards de-escalation and peace in the region. We continue to work closely with our partners and allies in calling for an immediate ceasefire."

Foreign Secretary David, Lammy said: "This package of UK support demonstrates our ongoing commitment to Lebanon’s only legitimate armed forces, forces essential for stability and security of the state and wider region. We continue to call for an immediate ceasefire between Lebanese Hizballah and Israel and a political plan consistent with UN Security Council Resolution 1701. That is the only way to restore security and stability for the people living on both sides of the border."

In October 2024, as a direct response to the mass displacement of people and growing number of civilian casualties, the UK boosted its humanitarian support for Lebanon with a further £10 million. The announcement follows the £5 million humanitarian package delivered through UNICEF to support access to clean water and sanitation, health, and nutrition supplies. The UK has also agreed to match public donations to the DEC Middle East Humanitarian Appeal of up to £10 million.

The UK government is completely committed to peace in the Middle East and continues to call for de-escalation in the region after being the first nation in the G7 to do so. A ceasefire would pave the way for civilians on both sides of the border to return to their homes.

www.gov.uk

In October 2024, as a direct response to the mass displacement of people and growing number of civilian casualties, the UK boosted its humanitarian support for Lebanon with a further £10 million. The announcement follows the £5 million humanitarian package delivered through UNICEF to support access to clean water and sanitation, health, and nutrition supplies. The UK has also agreed to match public donations to the DEC Middle East Humanitarian Appeal of up to £10 million.

The UK government is completely committed to peace in the Middle East and continues to call for de-escalation in the region after being the first nation in the G7 to do so. A ceasefire would pave the way for civilians on both sides of the border to return to their homes.

www.gov.uk

New Cargo Handling Facility Opens

Mission Critical Equipment for the Typhoon Force at RAF Coningsby is prepared for operations faster than ever in the Station’s new cargo handling facility.

In military language, the new building will allow RAF Coningsby to fulfil “Purple Gate Customs Bonding”. This means that military equipment and supplies can be properly stored once prepared for overseas movement, and that host nations know that the cargo is safe and legal.

Officer Commanding Logistics Squadron, Squadron Leader Phil Bishop, said: “The handling of military freight is a detailed business, especially when it’s going overseas. We must conform to our own customs standards, but also to the standards of the nation we’re deploying to. To do that safely and securely, and not get under anyone else’s feet, a dedicated building is essential.”

Biosecurity is a serious concern for Defence forces around the world. The unplanned introduction of foreign species can have far reaching effects. The new building will allow RAF Coningsby Movers to ensure that no indigenous British species are inadvertently exported to a partner nation inside the cargo.

Coningsby’s new cargo handling facility has plenty of space, is large enough to operate 16-tonne forklifts inside, and can hold enough freight to fill a C-17 Globemaster. The new cargo handling facility forms part of the RAF’s growing estate designed with sustainability at heart. The building includes solar panels, which provide the electricity it needs to be carbon neutral.

Royal Engineers from the Army provided oversight to the project. Captain Chris Davison said: “Value for the taxpayer is the thing. Milestone payments were only made when the work was completed to a high standard, and we made sure that the contractors and subcontractors followed health and safety legislation throughout the build. The new building has got to be safe, fit for purpose, and represent a good deal for Defence.”

The cargo handling facility will become the responsibility of RAF Coningsby’s Movements Section. RAF Movers are responsible for planning and executing the movement of RAF personnel and equipment by road, rail, air and sea.

Sergeant Mark Simpson oversees the Movements Section. He said: “Firstly, credit to my retired colleague Warrant Officer Mark Vaughan as the new building was his idea from the start. All RAF operations and exercises depend on Movers getting supplies and ground support equipment safely and correctly through the supply chain into the host nation. It’s going to make a massive difference; this building is perfectly designed to meet current and potential future regulations.”

Officially opened on 16th October by Wing Commander Nick Startup, Officer Commanding Base Support Wing, the building swung immediately into use. Wing Commander Startup said: “Firstly, congratulations to the team from Station Support Squadron in pulling this together. The Typhoon Force deploys all over the world, and this building allows our Movers to ensure the squadrons have the right equipment in the right place at the right time, to have what they need to fly and fight.”

raf.mod.com

In military language, the new building will allow RAF Coningsby to fulfil “Purple Gate Customs Bonding”. This means that military equipment and supplies can be properly stored once prepared for overseas movement, and that host nations know that the cargo is safe and legal.

Officer Commanding Logistics Squadron, Squadron Leader Phil Bishop, said: “The handling of military freight is a detailed business, especially when it’s going overseas. We must conform to our own customs standards, but also to the standards of the nation we’re deploying to. To do that safely and securely, and not get under anyone else’s feet, a dedicated building is essential.”

Biosecurity is a serious concern for Defence forces around the world. The unplanned introduction of foreign species can have far reaching effects. The new building will allow RAF Coningsby Movers to ensure that no indigenous British species are inadvertently exported to a partner nation inside the cargo.

Coningsby’s new cargo handling facility has plenty of space, is large enough to operate 16-tonne forklifts inside, and can hold enough freight to fill a C-17 Globemaster. The new cargo handling facility forms part of the RAF’s growing estate designed with sustainability at heart. The building includes solar panels, which provide the electricity it needs to be carbon neutral.

Royal Engineers from the Army provided oversight to the project. Captain Chris Davison said: “Value for the taxpayer is the thing. Milestone payments were only made when the work was completed to a high standard, and we made sure that the contractors and subcontractors followed health and safety legislation throughout the build. The new building has got to be safe, fit for purpose, and represent a good deal for Defence.”

The cargo handling facility will become the responsibility of RAF Coningsby’s Movements Section. RAF Movers are responsible for planning and executing the movement of RAF personnel and equipment by road, rail, air and sea.

Sergeant Mark Simpson oversees the Movements Section. He said: “Firstly, credit to my retired colleague Warrant Officer Mark Vaughan as the new building was his idea from the start. All RAF operations and exercises depend on Movers getting supplies and ground support equipment safely and correctly through the supply chain into the host nation. It’s going to make a massive difference; this building is perfectly designed to meet current and potential future regulations.”

Officially opened on 16th October by Wing Commander Nick Startup, Officer Commanding Base Support Wing, the building swung immediately into use. Wing Commander Startup said: “Firstly, congratulations to the team from Station Support Squadron in pulling this together. The Typhoon Force deploys all over the world, and this building allows our Movers to ensure the squadrons have the right equipment in the right place at the right time, to have what they need to fly and fight.”

raf.mod.com

From: Andy Spinks, Warkleigh, Devon

Subject: Cancelled Operations

Hi Tony,

One of my old passports has a visa for Chad, issued on 28 April 1978. Strangely, my logbook records that I was in Hong Kong - refors of the Airport Unit at Kai Tak during a busy period – on that date. So maybe we had two passports; I know I had two passports later in life but cannot remember if we had two passports while on UKMAMS.

Anyway, back to Chad. This was to be an exciting task. One C130, based in the Chad capital, N’Djamena, and flying to another African nation. It was all pretty hush-hush and I don’t think we were ever told what the operational location was, or what the load(s) would be. My atlas shows that Chad’s neighbours are Cameroon, Central African Republic, Libya, Niger, Nigeria and Sudan. However, we were briefed that we would be flying out of N’Djamena and overflying a neighbouring nation to reach the operational area. All very exciting until Ops told us that the whole operation had been cancelled because the “neighbouring nation” would not guarantee our safe overflight. I think that rules out flying over Sudan (it was safe – we had already done two tasks in Khartoum that year), Libya (because overflying Libya would just get to the Med), and Nigeria. Maybe we were destined to go to CAR, Niger or overflying them to reach Mali or the Congo - who knows? In the end, it was just a cancelled operation, which was hugely disappointing.

Many thanks for all the hard work, Tony, which is very much appreciated.

All the best

Andy

Yes Andy, we had two passports whilst on the squadron; one we carried with us and the other back at Base Ops where the admin bods could arrange for visas, if required, for our next task.

Subject: Cancelled Operations

Hi Tony,

One of my old passports has a visa for Chad, issued on 28 April 1978. Strangely, my logbook records that I was in Hong Kong - refors of the Airport Unit at Kai Tak during a busy period – on that date. So maybe we had two passports; I know I had two passports later in life but cannot remember if we had two passports while on UKMAMS.

Anyway, back to Chad. This was to be an exciting task. One C130, based in the Chad capital, N’Djamena, and flying to another African nation. It was all pretty hush-hush and I don’t think we were ever told what the operational location was, or what the load(s) would be. My atlas shows that Chad’s neighbours are Cameroon, Central African Republic, Libya, Niger, Nigeria and Sudan. However, we were briefed that we would be flying out of N’Djamena and overflying a neighbouring nation to reach the operational area. All very exciting until Ops told us that the whole operation had been cancelled because the “neighbouring nation” would not guarantee our safe overflight. I think that rules out flying over Sudan (it was safe – we had already done two tasks in Khartoum that year), Libya (because overflying Libya would just get to the Med), and Nigeria. Maybe we were destined to go to CAR, Niger or overflying them to reach Mali or the Congo - who knows? In the end, it was just a cancelled operation, which was hugely disappointing.

Many thanks for all the hard work, Tony, which is very much appreciated.

All the best

Andy

Yes Andy, we had two passports whilst on the squadron; one we carried with us and the other back at Base Ops where the admin bods could arrange for visas, if required, for our next task.

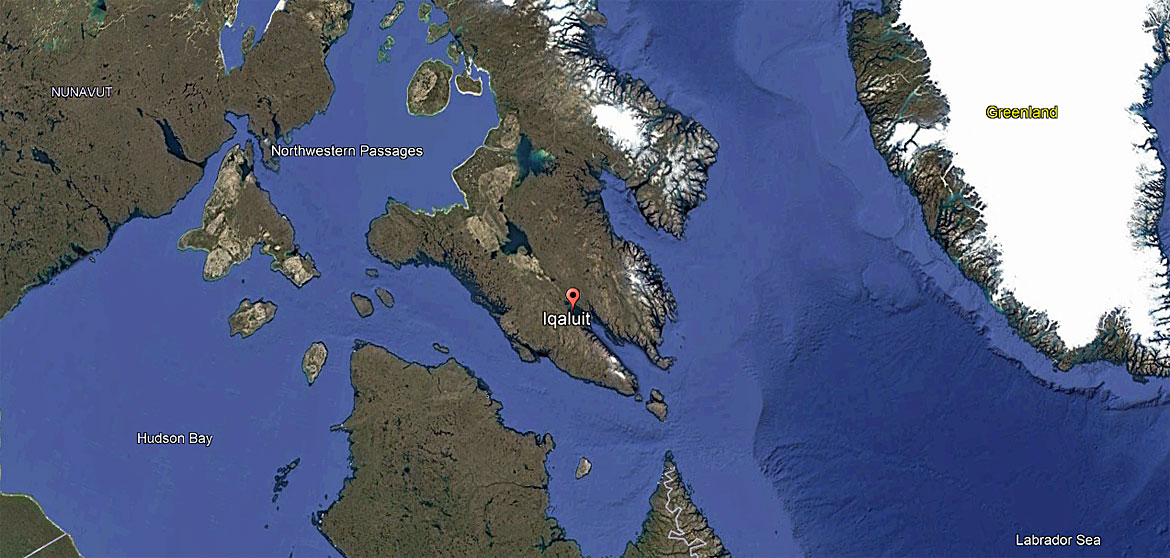

Air India flight leaves Iqaluit after Canadian military steps in

Passengers on Air India's flight 127 have finally made their way to Chicago, after the Canadian military took exceptional measures to get them out of Nunavut. An online bomb threat forced the plane, which was flying from New Delhi, to divert to Iqaluit early Tuesday morning, October 15.

A Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Airbus A-330 from Ontario's CFB Trenton whisked the 211 passengers and crew out of Iqaluit shortly before midnight Tuesday. Passengers spent 18 hours stranded at the Iqaluit airport's international security zone.

In a statement shared on X, Emergency Preparedness Minister Harjit Sajjan, said he approved a request for the Canadian military resources, as Iqaluit was "not equipped to house these passengers" and the airline "hasn't found a solution."

In a statement to CBC News, Canadian Armed Forces spokesperson Kened Sadiku said the military received a request for assistance from Public Safety Canada. It determined that "rapid relocation of an RCAF aircraft to bring the passengers to their original destination in Chicago was the best way forward to all involved, including the passengers," according to Sadiku.

It isn't the first time passengers have been stranded in Iqaluit after a flight diversion. Past incidents include a Swiss International Air Lines plane in 2017 and a Delta Airlines plane that saw passengers accommodated at a local bar, in 2014.

CBC News

A Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Airbus A-330 from Ontario's CFB Trenton whisked the 211 passengers and crew out of Iqaluit shortly before midnight Tuesday. Passengers spent 18 hours stranded at the Iqaluit airport's international security zone.

In a statement shared on X, Emergency Preparedness Minister Harjit Sajjan, said he approved a request for the Canadian military resources, as Iqaluit was "not equipped to house these passengers" and the airline "hasn't found a solution."

In a statement to CBC News, Canadian Armed Forces spokesperson Kened Sadiku said the military received a request for assistance from Public Safety Canada. It determined that "rapid relocation of an RCAF aircraft to bring the passengers to their original destination in Chicago was the best way forward to all involved, including the passengers," according to Sadiku.

It isn't the first time passengers have been stranded in Iqaluit after a flight diversion. Past incidents include a Swiss International Air Lines plane in 2017 and a Delta Airlines plane that saw passengers accommodated at a local bar, in 2014.

CBC News

New members who have joined us recently:

Welcome to the OBA

Members of 4624 Movements Squadron Royal Auxiliary Air Force

Louise Minihan-Lees, Bridgnorth, Salop

Steve Keene, Exeter, Devon

Mike Hall, Solihull, West Midlands

Martin Coombes, Ampney Crucis, Glos

David Degg, Coalville, Leics

Ivan “Matt” Dillon, Didcot, Oxon

Andy Burrows, Enfield, Greater London

Craig Vaux, Llanllwni, Carmarthenshire

Peter Tysoe, Dundee, Tayside

Eamonn Hackett, Northwich, Cheshire

The Start of the 24-25 Kiwi Antarctic Season

The Start of the 24-25 Kiwi Antarctic Season has thrown a few curve ball delays at us so we are well stocked on pallets to send but this week we are all about heavy machinery.

76,900 Lb drill rigg for Ant NZ loaded today for Monday's mission, a 33,000 LB T5 overhang crane boom for Tuesday and the 12,000 Lbs drill rigg cali bar (T4 overhang) went last week, 3 x helicopters already gone out too.

A crane and its boom and counter weights coming in over 110,000 Lbs to move later in the month along with another helicopter.

A lot of trips for the ACY SNCO I/Cs to contractor's yards and Smiths cranes to get measurements and putting together some load plans and shoring plans etc. This year's augmented staff have had to hit the ground running this season...

76,900 Lb drill rigg for Ant NZ loaded today for Monday's mission, a 33,000 LB T5 overhang crane boom for Tuesday and the 12,000 Lbs drill rigg cali bar (T4 overhang) went last week, 3 x helicopters already gone out too.

A crane and its boom and counter weights coming in over 110,000 Lbs to move later in the month along with another helicopter.

A lot of trips for the ACY SNCO I/Cs to contractor's yards and Smiths cranes to get measurements and putting together some load plans and shoring plans etc. This year's augmented staff have had to hit the ground running this season...

Operation Cat Drop

This Newsletter is Dedicated

to the Memories of:

Hugh Curran (RAF)

Paul Di'Annio (RAF)

Pierre Martin (RCAF)

to the Memories of:

Hugh Curran (RAF)

Paul Di'Annio (RAF)

Pierre Martin (RCAF)

Tony Gale

ukmamsoba@gmail.com

ukmamsoba@gmail.com