C130 completes its tour of duty and is replaced by the A400M Atlas

The last C130 squadron, providing the vital air bridge to UK personnel serving in and around the broader Middle East for the last 3 years, took to the skies for the final time in its operational role. It will be succeeded by the new Airbus A400M Atlas which will take over full squadron duties at the end of the month.

Although the A400M has undertaken sorties alongside the C130 before, this will be the first time one of its squadrons has deployed to the Middle East in an operational role.

Air Officer Commanding #83 EAG, Air Commodore Roddy Dennis, said: “The C130 crews both in the air and on the ground should be justifiably proud of their achievements. I thank them on behalf of 83 EAG for all their hard work in making our mission a success.”

Although the A400M has undertaken sorties alongside the C130 before, this will be the first time one of its squadrons has deployed to the Middle East in an operational role.

Air Officer Commanding #83 EAG, Air Commodore Roddy Dennis, said: “The C130 crews both in the air and on the ground should be justifiably proud of their achievements. I thank them on behalf of 83 EAG for all their hard work in making our mission a success.”

Royal Air Force

From: David Taylor, York

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #092917

Hello Tony,

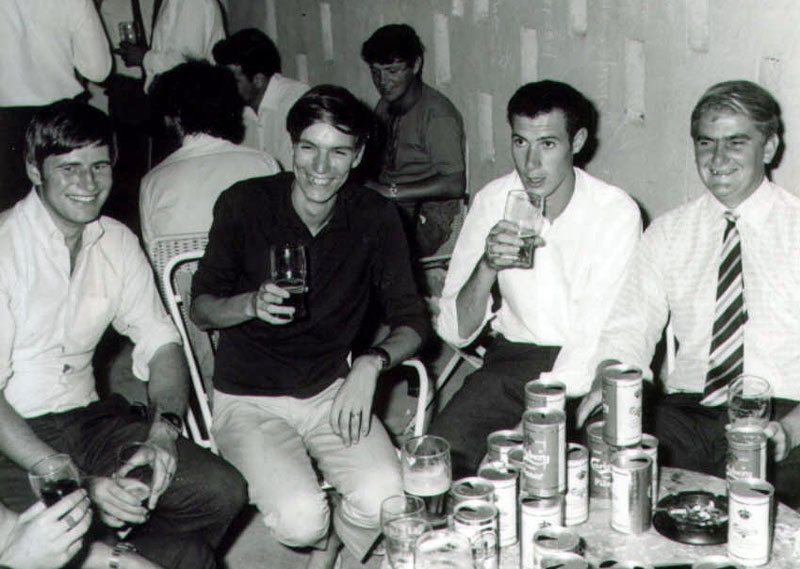

Many thanks for adding my name to the newsletter mailing list, brings back loads of memories. As stated previously, I was not MAMS but TCMSF, so we would often have worked together; I wonder if anyone recalls Ch/Tech Ron King, a Britannia crew chief of some reknown. If you worked with him you would certainly remember, especially when it got to bar time! Boy, could he drink! I recall a party we were invited to in Canberra, Oz. Some Aussies decided to try and drink Ron under the table; ended up with them sloping off to bed, completely zonked, with the somewhat slurred words, 'There are the keys, Ron, lock up when you decide to leave!"

Another story gives some idea of what we occasionally had to endure as word spread. Landing at Offut AFB, Nebraska, on a flight from Lyneham, via a refuelling stop at Gander, we were shown into a crew room where beer abounded. One of the Americans, obviously a Texan, wore the inevitable cowboy boots - although at present he didn’t have them on. His boots had been removed and put to a better use. They had been filled with beer, just as another Britannia crew were shown in, tired and parched. “Ah, here come some more Brits. Boy, can they ever drink beer!” said one of the Americans, offering a full boot. One eager crew member stepped forward, took the proffered footwear and proceeded to empty it in one go. Then, wiping his lips, he says, ‘Pity it wasn’t a size twelve." It was at times like that one felt proud to be British.

As for HKG, only made it up there when working on Sunderlands at RAF Seletar, Singapore - yeah, that long ago! One of the squadron’s duties was to have an aircraft continually based at Kai Tak on Search & Rescue (SAR) standby. The aircraft usually sat at anchor in the bay formed by the main runway, onshore, and the new runway, still under construction, which extended out into the harbour. I was lucky enough to find myself detached there for a six week period. With but a couple of training flights - and thankfully no emergencies - there was not a lot for us to do on base.

Downtown was an altogether different kettle of fish. Ah! the memories: Chanticleir - a restaurant bar on main street - forget the name now - Kowloon. Honolulu Bar: “Enchanting music for dancing, genuine (?) drinks , delicious food”, so stated their gaily-coloured business card. It was something all bars gave out, possibly so you could later remember where the hell it was you’d been the previous night. They still adorn the inside covers of my photo albums. Lucky Star Bar & Nightclub was another, in the Wanchai district - oh, oh, Suzie Wong territory, that. Think maybe I met her sister. Said she wanted to improve her English, didn’t she? And here’s me, assuming she meant the language!

Subject: Re: UKMAMS OBA OBB #092917

Hello Tony,

Many thanks for adding my name to the newsletter mailing list, brings back loads of memories. As stated previously, I was not MAMS but TCMSF, so we would often have worked together; I wonder if anyone recalls Ch/Tech Ron King, a Britannia crew chief of some reknown. If you worked with him you would certainly remember, especially when it got to bar time! Boy, could he drink! I recall a party we were invited to in Canberra, Oz. Some Aussies decided to try and drink Ron under the table; ended up with them sloping off to bed, completely zonked, with the somewhat slurred words, 'There are the keys, Ron, lock up when you decide to leave!"

Another story gives some idea of what we occasionally had to endure as word spread. Landing at Offut AFB, Nebraska, on a flight from Lyneham, via a refuelling stop at Gander, we were shown into a crew room where beer abounded. One of the Americans, obviously a Texan, wore the inevitable cowboy boots - although at present he didn’t have them on. His boots had been removed and put to a better use. They had been filled with beer, just as another Britannia crew were shown in, tired and parched. “Ah, here come some more Brits. Boy, can they ever drink beer!” said one of the Americans, offering a full boot. One eager crew member stepped forward, took the proffered footwear and proceeded to empty it in one go. Then, wiping his lips, he says, ‘Pity it wasn’t a size twelve." It was at times like that one felt proud to be British.

As for HKG, only made it up there when working on Sunderlands at RAF Seletar, Singapore - yeah, that long ago! One of the squadron’s duties was to have an aircraft continually based at Kai Tak on Search & Rescue (SAR) standby. The aircraft usually sat at anchor in the bay formed by the main runway, onshore, and the new runway, still under construction, which extended out into the harbour. I was lucky enough to find myself detached there for a six week period. With but a couple of training flights - and thankfully no emergencies - there was not a lot for us to do on base.

Downtown was an altogether different kettle of fish. Ah! the memories: Chanticleir - a restaurant bar on main street - forget the name now - Kowloon. Honolulu Bar: “Enchanting music for dancing, genuine (?) drinks , delicious food”, so stated their gaily-coloured business card. It was something all bars gave out, possibly so you could later remember where the hell it was you’d been the previous night. They still adorn the inside covers of my photo albums. Lucky Star Bar & Nightclub was another, in the Wanchai district - oh, oh, Suzie Wong territory, that. Think maybe I met her sister. Said she wanted to improve her English, didn’t she? And here’s me, assuming she meant the language!

Best wishes to you all and I look forward to reading more stories in the future.

Dave

Dave

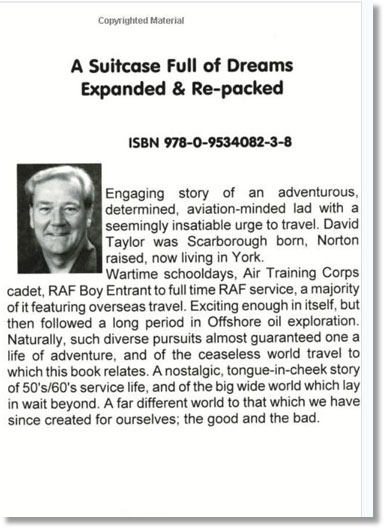

I have written an autobiography, published on Amazon: "A Suitcase Full of Dreams - Expanded & Re-Packed" (as it is an updated version) ISBN 978-0-9534082-3-8.

From: Nigel Moore, Devauden, Mon

Subject: Memories of Kai Tak

I came across the OBA site whilst doing some research and although I never served on MAMS I spent quite some time on “Mover” posts including Kai Tak having been posted there in November 1975 from the wilds of Lincolnshire. Your memories of Kai Tak has sparked this email.

The SAMO was Sqn Ldr John Sims with Flt Lt Eric Webely as DSAMO. I joined Brian Hunt as the shift DAMO’s, my post having been temporarily filled by a MAMS officer, Flt Lt Andy MacClean. Eric was replaced by Flt Lt Barry Simons. Kai Tak was bachelor heaven in-between work! Memorable trips included many to Nepal helping out with the Gurkha rotation run by MAMS in Kathmandu - evenings at “Brit House” were somewhat cloudy.

38 Group were more than kind authorising trips to assist with the Honour Guard rotation in Seoul - where the hotel bar/night club was christened, "The Upholstered Sewer" by the C-130 Air Engineer, MEng Nick Nicholls. I well remember a most fascinating two weeks with 6 Gurkha Regiment in Borneo, also a lengthy trip to the Philippines delivering aid following a substantial hurricane that hit the southern island of Mindanao - we were only allowed into Manila but the Philippines Air Force were kind enough to back-load a considerable quantity of Sam Miguel!

MAMS were supporting the Gurkha rotation, including my future best man, Flt Lt Geoff Elliott. Don Hunter was a regular visitor, as were many Movers from Gan and Singapore; those from the former stations spending much needed R&R in the hot spots of our lost empire!

Subject: Memories of Kai Tak

I came across the OBA site whilst doing some research and although I never served on MAMS I spent quite some time on “Mover” posts including Kai Tak having been posted there in November 1975 from the wilds of Lincolnshire. Your memories of Kai Tak has sparked this email.

The SAMO was Sqn Ldr John Sims with Flt Lt Eric Webely as DSAMO. I joined Brian Hunt as the shift DAMO’s, my post having been temporarily filled by a MAMS officer, Flt Lt Andy MacClean. Eric was replaced by Flt Lt Barry Simons. Kai Tak was bachelor heaven in-between work! Memorable trips included many to Nepal helping out with the Gurkha rotation run by MAMS in Kathmandu - evenings at “Brit House” were somewhat cloudy.

38 Group were more than kind authorising trips to assist with the Honour Guard rotation in Seoul - where the hotel bar/night club was christened, "The Upholstered Sewer" by the C-130 Air Engineer, MEng Nick Nicholls. I well remember a most fascinating two weeks with 6 Gurkha Regiment in Borneo, also a lengthy trip to the Philippines delivering aid following a substantial hurricane that hit the southern island of Mindanao - we were only allowed into Manila but the Philippines Air Force were kind enough to back-load a considerable quantity of Sam Miguel!

MAMS were supporting the Gurkha rotation, including my future best man, Flt Lt Geoff Elliott. Don Hunter was a regular visitor, as were many Movers from Gan and Singapore; those from the former stations spending much needed R&R in the hot spots of our lost empire!

With the planned draw-down (aka closure) of RAF Kai Tak, HQSTC bean-counters then struck with a handling contract going to Cathay Pacific and my dealings with Cathay management - Gerry Pengelly, Derek Smith and Mike Hambley - led to a frantic time at the airport in resolving many issues, including negotiating in-flight rations with the ALM’s and training the Cathay staff to produce trim sheets which we signed!

The SAMO slot was dispensed with and we were then “commanded” by aircrew; firstly, Sqn Ldr John Brown - any mover recall the KD shorts? - and later by another Brown - Sqn Ldr Mike Brown. Due to the downsizing and the handling contract Brian Hunt was short toured based on the new found principal of “first in first out” and we eventually moved from RAF Kai Tak to offices in what would now be called an “industrial unit" at the airport.

Happy days indeed and kind regards to any member who knew me.

Nigel Moore

The SAMO slot was dispensed with and we were then “commanded” by aircrew; firstly, Sqn Ldr John Brown - any mover recall the KD shorts? - and later by another Brown - Sqn Ldr Mike Brown. Due to the downsizing and the handling contract Brian Hunt was short toured based on the new found principal of “first in first out” and we eventually moved from RAF Kai Tak to offices in what would now be called an “industrial unit" at the airport.

Happy days indeed and kind regards to any member who knew me.

Nigel Moore

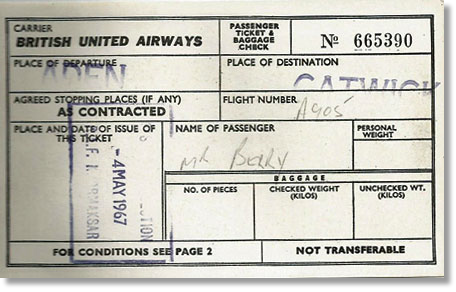

From: Ian Berry, West Swindon

Subject: Memories of Aden

After reading Mike Stepney’s recollections he got my memory going too... unlike my local good friends Colin Allen, Gordon Black and the sadly now departed Terry Roberts, fortunately I only had to serve a 100 day emergency detachment.

"Be prepared as it will come in fits and starts...” I was once warned. I was deployed in late January 1966 and proceeded to RAF Innsworth in Gloucester where I met the rest of my detachment. There were lots of jabs and doctor checkups plus the new kit issues including below the knee KD, nice new blue pyjamas and a kitbag to put it all in.

After a night in transit it was off to RAF Hendon, to wait. We spent two nights in an even worse transit block; there were 40 men to a room and only a small shelf to hold our personal stuff.

Finally it was off to Gatwick Airport by coach there to board a brand new British United Airways (BUA) VC-10. What a contradiction with comparative luxury as compared to the past few days.

Some six hours later, in the early hours, we arrived at Khormaksar. The smell! The heat! From there we boarded an armoured 39-seater coach (grills on the windows and an onboard escort armed with a sten gun) for our journey to RAF Steamer Point. That same evening there had been a grenade attack on the cinema queue waiting to enter HMS Sheba. Arriving halfway up Chapel Hill we collected our bedding to the cries of “Mooney” from a few drunks!

Subject: Memories of Aden

After reading Mike Stepney’s recollections he got my memory going too... unlike my local good friends Colin Allen, Gordon Black and the sadly now departed Terry Roberts, fortunately I only had to serve a 100 day emergency detachment.

"Be prepared as it will come in fits and starts...” I was once warned. I was deployed in late January 1966 and proceeded to RAF Innsworth in Gloucester where I met the rest of my detachment. There were lots of jabs and doctor checkups plus the new kit issues including below the knee KD, nice new blue pyjamas and a kitbag to put it all in.

After a night in transit it was off to RAF Hendon, to wait. We spent two nights in an even worse transit block; there were 40 men to a room and only a small shelf to hold our personal stuff.

Finally it was off to Gatwick Airport by coach there to board a brand new British United Airways (BUA) VC-10. What a contradiction with comparative luxury as compared to the past few days.

Some six hours later, in the early hours, we arrived at Khormaksar. The smell! The heat! From there we boarded an armoured 39-seater coach (grills on the windows and an onboard escort armed with a sten gun) for our journey to RAF Steamer Point. That same evening there had been a grenade attack on the cinema queue waiting to enter HMS Sheba. Arriving halfway up Chapel Hill we collected our bedding to the cries of “Mooney” from a few drunks!

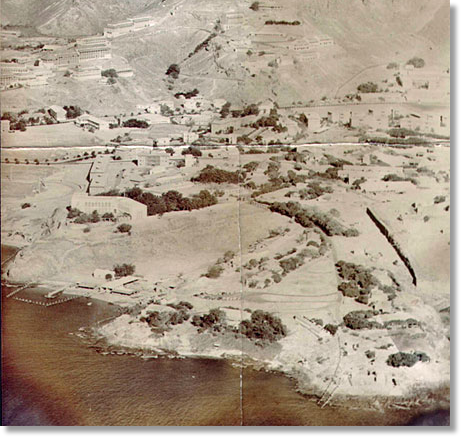

Steamer Point, Aden.Maidan Club, bottom left - Elephant

Bay, right - Chapel Hill, centre left and Crater behind the

hills at rear.

Bay, right - Chapel Hill, centre left and Crater behind the

hills at rear.

This barrack block was to be my home for the next 100 days. I was to work in 114MU across the main road (either side protected by a big wire fence and armed guards). A lot of things are a blur and others quite vivid. I do remember the last two C47 Dakotas operated by the RAF at Khormaksar. By the beach we had the Maidan Club and the Mermaid Club. All of the bars sold what was quite lethal draft Tiger Beer!

There were probably 8-10 army battalions providing security at this time. Our area was covered by the Cameronians, known as the Poison Dwarfs; hard and evil Scotsmen! They lived around the corner in Elephant Bay. In Tawahi itself the cover was provided by the Lancashire Fusiliers.

The sun was fierce and I learnt the hard way about nylon shirts offering no protection when I received third degree burns across my shoulders and arms, there are marks on my arms to this day. I also had the misfortune to go down with “Aden Gut” and spent four days in the Med Centre losing body fluids from all orifices and just wanting to die; not a recommended way of losing weight! We “Erks” were armed with .303 Lee-Enfield rifles whereas the squaddies had the new 7.62 SLRs. Five rounds and make them count!

I had just turned 18 at this stage and was quite naive in some matters. It was in Aden I actually tasted my first curry after gate crashing the Police Club. I also tasted tuna for the first time. Work at 114MU was becoming tedious and all because of some idiot permanent staff sergeant. We were employed in this huge shed and as there were copious amounts of red lead paint he had us painting the floor every week using brooms instead of brushes. The intention was to ship out the contents of the sheds back to Muharraq or UK using the huge empty aero engine boxes stored outside. I seem to recall that one of these crates was not empty and they discovered an Avon engine for a Hawker Hunter inside!

There were probably 8-10 army battalions providing security at this time. Our area was covered by the Cameronians, known as the Poison Dwarfs; hard and evil Scotsmen! They lived around the corner in Elephant Bay. In Tawahi itself the cover was provided by the Lancashire Fusiliers.

The sun was fierce and I learnt the hard way about nylon shirts offering no protection when I received third degree burns across my shoulders and arms, there are marks on my arms to this day. I also had the misfortune to go down with “Aden Gut” and spent four days in the Med Centre losing body fluids from all orifices and just wanting to die; not a recommended way of losing weight! We “Erks” were armed with .303 Lee-Enfield rifles whereas the squaddies had the new 7.62 SLRs. Five rounds and make them count!

I had just turned 18 at this stage and was quite naive in some matters. It was in Aden I actually tasted my first curry after gate crashing the Police Club. I also tasted tuna for the first time. Work at 114MU was becoming tedious and all because of some idiot permanent staff sergeant. We were employed in this huge shed and as there were copious amounts of red lead paint he had us painting the floor every week using brooms instead of brushes. The intention was to ship out the contents of the sheds back to Muharraq or UK using the huge empty aero engine boxes stored outside. I seem to recall that one of these crates was not empty and they discovered an Avon engine for a Hawker Hunter inside!

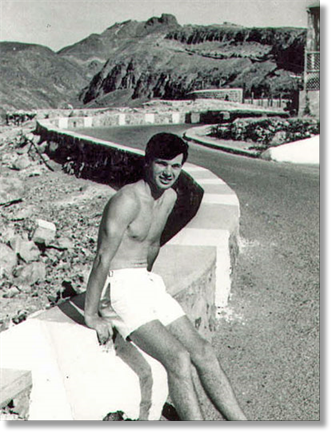

Yours truly on Chapel Hill - March 1967

One Monday we couldn’t paint the shed floor; seemingly all of the brushes were on their way to Muharraq!

Rumour also had it that the Movers at Khormaksar never got on with their counterparts in Muharraq. Things came to a head when the Khormaksar Movers loaded a dismantled aircraft arrestor barrier in the lower holds of a Britannia and then proceeded to reassemble it inside the hold. After two days on the pans at Muharraq they signalled, “Ok we give up, how did you load it?”

The food in Aden was something else, absolutely awful. Anyone who was there can remember that even every chip had at least three black eyes in it from the rotting potatoes. This was due to the four months stock of rations held in the ASD (Aden Supply Depot), the oldest being used first. I recollect Bromide flavoured tea too.

Rumour also had it that the Movers at Khormaksar never got on with their counterparts in Muharraq. Things came to a head when the Khormaksar Movers loaded a dismantled aircraft arrestor barrier in the lower holds of a Britannia and then proceeded to reassemble it inside the hold. After two days on the pans at Muharraq they signalled, “Ok we give up, how did you load it?”

The food in Aden was something else, absolutely awful. Anyone who was there can remember that even every chip had at least three black eyes in it from the rotting potatoes. This was due to the four months stock of rations held in the ASD (Aden Supply Depot), the oldest being used first. I recollect Bromide flavoured tea too.

We all had our personal set of eating irons and there was a place just outside the mess door where they could be washed. Quite often an unfortunate airman would be spotted trying to fish his eating irons out of a boiling hot cauldron of scum covered water after having accidentally dropped them in! This was probably the cause of my illness that I had mentioned earlier.

As time progressed the security situation did worsen and, just like Mike Stepney, I had a free ride back from Tawahi once in the back of a Landrover when there was a grenade attack. In reality it sounds much louder than in the movies.

Our General Duties Training also went on for a long while as there was so much to digest and warnings of booby traps and grenade drills. The lessons obviously worked as I remember what looked like an expensive Parker pen lying in the bondu for weeks as nobody would go near it...

There was a curfew between midnight and 06.00 and anyone caught out of bounds after that were fined £1 a minute. I do recall two SNCOs being caught out of bounds at 00.50am and were fined £50.00. That was well over a week’s wages.

As time progressed the security situation did worsen and, just like Mike Stepney, I had a free ride back from Tawahi once in the back of a Landrover when there was a grenade attack. In reality it sounds much louder than in the movies.

Our General Duties Training also went on for a long while as there was so much to digest and warnings of booby traps and grenade drills. The lessons obviously worked as I remember what looked like an expensive Parker pen lying in the bondu for weeks as nobody would go near it...

There was a curfew between midnight and 06.00 and anyone caught out of bounds after that were fined £1 a minute. I do recall two SNCOs being caught out of bounds at 00.50am and were fined £50.00. That was well over a week’s wages.

Silent Valley - British Military Cemetery

Was there anything good about Aden? I think the only thing was the duty free goods were really, really cheap. I still have a pair of Zenith 10 x 50 binoculars that I bought in Aden for £5.

Well, all good things come to an end and on 4th May, 1967 my time was up; I was going home. I boarded a BUA Britannia via Tehran and Athens where there had just been a coup staged by some Greek Colonels. The in-flight breakfast on board that aircraft was the best meal I had eaten in four months!

On arrival home there I was, young, fit, tanned and with a medal too. I was also told that Aden was the worst posting in the world... they lied! 18 months later I arrived at El Adem in Libya.

Well, all good things come to an end and on 4th May, 1967 my time was up; I was going home. I boarded a BUA Britannia via Tehran and Athens where there had just been a coup staged by some Greek Colonels. The in-flight breakfast on board that aircraft was the best meal I had eaten in four months!

On arrival home there I was, young, fit, tanned and with a medal too. I was also told that Aden was the worst posting in the world... they lied! 18 months later I arrived at El Adem in Libya.

Spartan 'ain't afraid of no dirt...

Our C-27J Spartans recently kicked up dust in remote parts of Western Australia and South Australia to test their off road capabilities.

Exercise Spartan Dawn saw them landing on a series of surfaces, including on a dry river bed and the Eyre Highway to test the Spartan's unique landing abilities.

The activity was also an opportunity to work with our mates in the South Australia Police and Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia in reducing the isolation of our remote communities.

airforce.gov.au

Exercise Spartan Dawn saw them landing on a series of surfaces, including on a dry river bed and the Eyre Highway to test the Spartan's unique landing abilities.

The activity was also an opportunity to work with our mates in the South Australia Police and Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia in reducing the isolation of our remote communities.

airforce.gov.au

ANTIPODEAN MOVERS’ FUN IN THE SUN

~ or ~

JUST ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE ...

[Mike “OBie” O’Brien, formerly FLTLT, 2 i/c UNTAC MCG]

~ or ~

JUST ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE ...

[Mike “OBie” O’Brien, formerly FLTLT, 2 i/c UNTAC MCG]

Introduction Cambodia, a South East Asian/Indochinese paradise, like its’ neighbours, had enjoyed a ‘reasonably sedate existence’ from antiquity ‘till the mid-1800's, and then enjoyed the gentle guiding hand of European Masters as a French Protectorate, until gaining Independence in 1953. From that period until March 1970, the country quietly progressed with the rest of South East Asia, and apart from some minor interruptions to its peaceful existence by the ‘police actions’ in neighbouring Laos and Vietnam, in the late 60's, the Republic of Cambodia basked in the glow of being considered the Paris of the East.

However, from Lon Nol's coup, establishing the Khmer Republic, in 1970, until April-May 1975, the Republic suffered numerous civil wars amongst the numerous factions who considered themselves best suited to rule this paradise.

Then, enter Pol Pot, whose absolute despotism during the next four years, turned Cambodia into a charnel house.

After the Vietnamese intervention in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and world-wide attention, the “The Supreme National Council” was the very painfully-conceived result of a tenuous union between the major players, the National Government of Cambodia and the State of Cambodia, and would represent Cambodian Sovereignty until the United Nations elections could be held, scheduled for mid-1993.

The UN Security Council Resolutions [Nos. 717 (1991), 728 and 745 (1992)], inter-alia, authorised the resolution of the problem in Cambodia by the creation of, initially, the United Nations Advance Mission in Cambodia, UNAMIC (in French: le Mission Préparatoire des Nations Uniés au Cambodge - MIPRENUC), established to 'pave the way' for UNTAC (the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia; or in French: l'Autorité Provisoire des Nations Unié au Cambodge - APRONUC), mandated to commence in February 1992. The primary aim was that the personnel be deployed as quickly as possible after the Peace Agreement was signed in Paris, in October 1991. Accordingly, In order to deploy the 16,000 military personnel and 5,000 civilians, Movement Control and Reception/Concentration Centres were to be established outside Cambodia to induct, and coordinate the orderly deployment into the mission area.

Then, enter Pol Pot, whose absolute despotism during the next four years, turned Cambodia into a charnel house.

After the Vietnamese intervention in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and world-wide attention, the “The Supreme National Council” was the very painfully-conceived result of a tenuous union between the major players, the National Government of Cambodia and the State of Cambodia, and would represent Cambodian Sovereignty until the United Nations elections could be held, scheduled for mid-1993.

The UN Security Council Resolutions [Nos. 717 (1991), 728 and 745 (1992)], inter-alia, authorised the resolution of the problem in Cambodia by the creation of, initially, the United Nations Advance Mission in Cambodia, UNAMIC (in French: le Mission Préparatoire des Nations Uniés au Cambodge - MIPRENUC), established to 'pave the way' for UNTAC (the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia; or in French: l'Autorité Provisoire des Nations Unié au Cambodge - APRONUC), mandated to commence in February 1992. The primary aim was that the personnel be deployed as quickly as possible after the Peace Agreement was signed in Paris, in October 1991. Accordingly, In order to deploy the 16,000 military personnel and 5,000 civilians, Movement Control and Reception/Concentration Centres were to be established outside Cambodia to induct, and coordinate the orderly deployment into the mission area.

In early 1992, pending the elections, the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) was created with the responsibility to:

I.

Oversee the demobilisation of 70% of the military forces of all parties.

II.

Supervise the cantoning of the military forces whilst retraining and regrouping was conducted.

III.

Assist and control internal security and police forces, and monitor the ceasefire.

IV.

Verify the cessation of external aid to the military forces of the parties.

V.

Ensure the absence of coercion in the repatriation of the refugees.

VI.

Assist with reconstruction of the civil infrastructure.

VII.

Organise and run the elections.

What’s all this got to do with Antipodean Movers?

The Canadian Government had provided some Logistics personnel to commence the Reception / Concentration tasks with their commitment to UNAMIC, and the Danish Government had initially offered a Movement Control capability, but withdrew it in early April 1992. To counter the capability shortfall the Australian Government provided a Movement Control Group, a concept which had been trialled over the previous few years in large-scale tri-Service Excercises, and had proven successful, especially during the civilian airlines’ pilots strike in August 1989, which coincided with the redeployment activities at the end of Exercise Kangaroo 89. For UNTAC, the tasks, initially, were considered to be those of Headquarters-level management and coordination of the deployment activities.

The Australian Government was quite specific that the deployment was to be for a maximum of four months only. The personnel, drawn from all over Australia were formally advised Fri 1 May 1992, and concentrated at Randwick Army Barracks, Sydney, on Tues 5 May for pre-deployment preparation; they departed by commercial passenger flight Mon 11 May, via Melbourne, with an overnight stop in Bangkok. Onwards movement from Bangkok was by a UN Flight operated by a French Air Force Transall, which arrived in Phnom Penh at 1000 hrs, 12 May 92. Amongst the ADF group of 30 personnel were seven Navy, 16 Army, and three RAAF Officers and four SNCOs, with Army to provide the Officer Commanding, and Air Force the 2IC. The lucky RAAF participants were the author, (then) FLTLT Mike “OBie” O’Brien as 2IC, and contributors, (then) FLTLTs Neil Collie (recently ex-RAF), and Steve Force, WOFF Errol Reidlinger, FSGTs Neil Gray and Wayne Riddle and SGT George Molnar, all of whom were RAAF Air Movements (and multi-modal transport) qualified.

The Canadian Government had provided some Logistics personnel to commence the Reception / Concentration tasks with their commitment to UNAMIC, and the Danish Government had initially offered a Movement Control capability, but withdrew it in early April 1992. To counter the capability shortfall the Australian Government provided a Movement Control Group, a concept which had been trialled over the previous few years in large-scale tri-Service Excercises, and had proven successful, especially during the civilian airlines’ pilots strike in August 1989, which coincided with the redeployment activities at the end of Exercise Kangaroo 89. For UNTAC, the tasks, initially, were considered to be those of Headquarters-level management and coordination of the deployment activities.

The Australian Government was quite specific that the deployment was to be for a maximum of four months only. The personnel, drawn from all over Australia were formally advised Fri 1 May 1992, and concentrated at Randwick Army Barracks, Sydney, on Tues 5 May for pre-deployment preparation; they departed by commercial passenger flight Mon 11 May, via Melbourne, with an overnight stop in Bangkok. Onwards movement from Bangkok was by a UN Flight operated by a French Air Force Transall, which arrived in Phnom Penh at 1000 hrs, 12 May 92. Amongst the ADF group of 30 personnel were seven Navy, 16 Army, and three RAAF Officers and four SNCOs, with Army to provide the Officer Commanding, and Air Force the 2IC. The lucky RAAF participants were the author, (then) FLTLT Mike “OBie” O’Brien as 2IC, and contributors, (then) FLTLTs Neil Collie (recently ex-RAF), and Steve Force, WOFF Errol Reidlinger, FSGTs Neil Gray and Wayne Riddle and SGT George Molnar, all of whom were RAAF Air Movements (and multi-modal transport) qualified.

Upon arrival at Phnom Penh we were accommodated at “Pteah Australii”, the home of the UNTAC ANZAC Force Communications Unit, for three days, until other accommodations could be arranged in Phnom Penh city for the Headquarters wallahs, and deployment to the up-country locations for the 'MovCon Det' personnel, like Siem Reap, Battambang and Kompong Soam in Cambodia, and U-Tapao, near Pattaya, and Bangkok, Thailand(!). Our accommodation separate to the other Australian personnel was to reinforce our “UNTAC HQ status”, as distinct from the Australian Contingent chain of command.

Accordingly, we lived in 'hotels' of varying degrees of salubriousness and economic status, and which at first was seen as good fun, but after a while the constant noise of traffic and the ever-present ‘nightly-‘ and 'pre-dawn choruses' of horizontal enjoyment, construction, funeral processions and general cacophony became a bit wearying. Similarly, the 'eating-out' novelty soon wore off; there not being much variety in the wine-lists and 'blue steak' was just unheard of.

Accordingly, we lived in 'hotels' of varying degrees of salubriousness and economic status, and which at first was seen as good fun, but after a while the constant noise of traffic and the ever-present ‘nightly-‘ and 'pre-dawn choruses' of horizontal enjoyment, construction, funeral processions and general cacophony became a bit wearying. Similarly, the 'eating-out' novelty soon wore off; there not being much variety in the wine-lists and 'blue steak' was just unheard of.

The Australian Movement Control Group pre-boarding UN Transall at Don Muang Airport, Bangkok

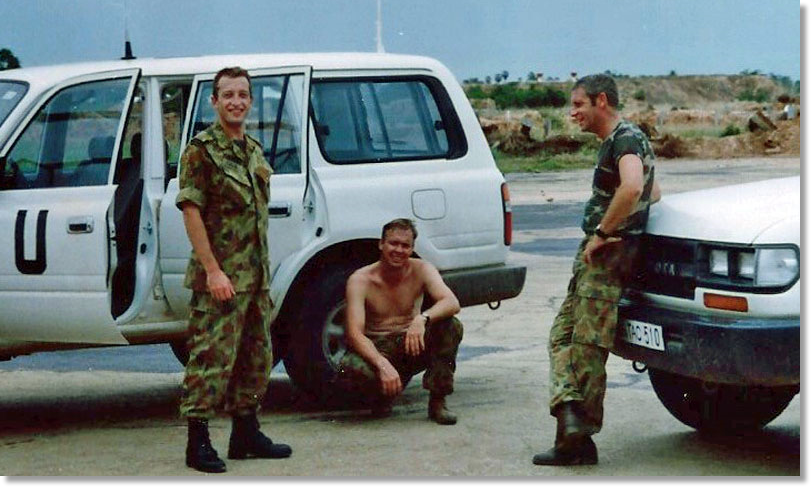

Some of the vehicles donated by Japan, less than six weeks after receipt!

Hotel Restaurant-Dancing Neak Poan

"Rates hourly by negotiation."

"Rates hourly by negotiation."

The UN 'working' hours, 0800-1200, 1400-1800 Mon to Sun inclusive, were designed to take into account the necessity of conserving energy during the hottest part of the day, and also to account for the enormous influx of people demanding sustenance from the very meagre resources; in effect, initially there were just not enough restaurants to cater for the thousands of UN personnel flooding into Phnom Penh, all of whom expected to be fed at the same time. There was soon, however, a noticeable increase in restaurants catering to the UN tastes, and allowances’ largesse, within the first couple of months.

Similarly, a commensurate increase in surface traffic, mostly white 4WD Toyotas and Nissans, was experienced; in fact, Phnom Penh was the most frustrating of cities in which to drive as there appeared to be a complete absence of road rules, not only on the part of the Cambodians, but moreso, the UN drivers, some of whom were less than competent. Amusingly, we were the ones who instituted, and issued, a record of UNTAC Driver's Licences, and were somewhat bemused by the battalion-sized contingents who arrived with consecutively-numbered home-nation licences, all issued on the same date, and the majority of whom proceeded to disprove the veracity of those same documents. This was indeed a portent of the driving “skills” I was to encounter in many future [all!] UN Missions.

Similarly, a commensurate increase in surface traffic, mostly white 4WD Toyotas and Nissans, was experienced; in fact, Phnom Penh was the most frustrating of cities in which to drive as there appeared to be a complete absence of road rules, not only on the part of the Cambodians, but moreso, the UN drivers, some of whom were less than competent. Amusingly, we were the ones who instituted, and issued, a record of UNTAC Driver's Licences, and were somewhat bemused by the battalion-sized contingents who arrived with consecutively-numbered home-nation licences, all issued on the same date, and the majority of whom proceeded to disprove the veracity of those same documents. This was indeed a portent of the driving “skills” I was to encounter in many future [all!] UN Missions.

Initially the Australian 'MovCon' personnel were regarded with considerable suspicion by some of the already 'well established' nationalities from the forerunner UNAMIC Mission who had 'settled in' so to speak, and were accordingly reluctant to share their power. An example is the UNAMIC Force Commander, provided by a previous colonial master, who had been 'relegated' to the appointment of Deputy Force Commander of UNTAC. There was quite a degree of animosity on behalf of some of the personnel who considered that they had prior rights to the transport assets as they were provided by their country, and other nationalities should not have any say in their disposition or use.

Until our arrival there had been no form of accountability, or passenger / freight /cargo documentation for any of the modes of transport being used by the UN. The usual procedure for having anything or anyone carried by air (helicopter or fixed wing) was to turn up at the airport(s) and cajole the crew into carrying the item, and then hoping that the aircraft would proceed to the destination advertised, and that the cargo would be unloaded, and given to whom it was intended. Notwithstanding that, the UN agencies IATA and ICAO are responsible for promulgation of airway regulations and Dangerous Goods Transportation Regulations, none of the operators in Cambodia in May '92 seemed to be too concerned about what they carried.

There was a “tasking office”, in operation, also provided by a previous colonial master, whose stated purpose was to allocate flights to effect sustainment and support operations, however their parochial attitude more often than not precluded efficient use of the resources … pencil-drawn wall charts are quite easily ‘amended’, depending on the attributes of the requester!

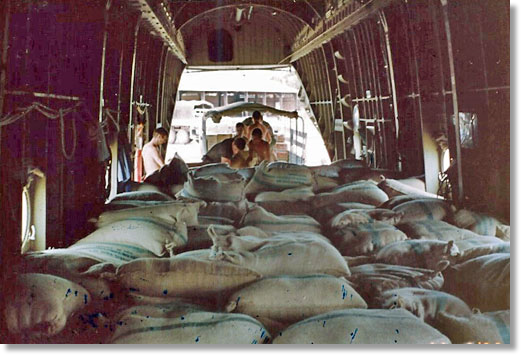

One of the Australians' first tasks, therefore, was the institution of International Standard Transportation procedures, for example manifesting of cargo, be it 'self-loading or otherwise'. We quickly realised that our tasking would extend beyond HQ/management duties to encompass ‘a hands-on approach’ to ensure the capability available would be best-used. The majority of the work performed by the RAAF personnel was to coordinate, and facilitate the application of air transportation procedures; implementation of this was extremely difficult, as was application of the rules and regulations pertaining to storage of dangerous cargo and explosives. As Australia is a signatory to the UN agencies' transportation regulations, the Department of Defence follows these rigorously, with exceptions only approved in times of declared national emergency. The picture below is yours truly, "Not quite in accordance with DG Storage Regs."

Until our arrival there had been no form of accountability, or passenger / freight /cargo documentation for any of the modes of transport being used by the UN. The usual procedure for having anything or anyone carried by air (helicopter or fixed wing) was to turn up at the airport(s) and cajole the crew into carrying the item, and then hoping that the aircraft would proceed to the destination advertised, and that the cargo would be unloaded, and given to whom it was intended. Notwithstanding that, the UN agencies IATA and ICAO are responsible for promulgation of airway regulations and Dangerous Goods Transportation Regulations, none of the operators in Cambodia in May '92 seemed to be too concerned about what they carried.

There was a “tasking office”, in operation, also provided by a previous colonial master, whose stated purpose was to allocate flights to effect sustainment and support operations, however their parochial attitude more often than not precluded efficient use of the resources … pencil-drawn wall charts are quite easily ‘amended’, depending on the attributes of the requester!

One of the Australians' first tasks, therefore, was the institution of International Standard Transportation procedures, for example manifesting of cargo, be it 'self-loading or otherwise'. We quickly realised that our tasking would extend beyond HQ/management duties to encompass ‘a hands-on approach’ to ensure the capability available would be best-used. The majority of the work performed by the RAAF personnel was to coordinate, and facilitate the application of air transportation procedures; implementation of this was extremely difficult, as was application of the rules and regulations pertaining to storage of dangerous cargo and explosives. As Australia is a signatory to the UN agencies' transportation regulations, the Department of Defence follows these rigorously, with exceptions only approved in times of declared national emergency. The picture below is yours truly, "Not quite in accordance with DG Storage Regs."

A task which took considerably longer to succeed at was that of coordinating airframe usage to capability, and forecasting requirements and loads (to reduce the wastage of flying empty airframes around the country on 'positioning legs'), and 'flight following / notification' (maintaining communications with aircraft to enhance safety). This problem was not as great in respect of riverine, sea and land transport, and I believe that 'nationalities' had a great deal to do with this.

Due to the variety of national military forces in country there were considerable differences in the way problems were approached ... from the 'get stuck in and have a go' style, to the 'if we ignore it, it will go away' approach. It took us nearly two months to be 'allowed' to trial an Air Movements Operations Coordination Centre (“AMOCC”, apt indeed!), which was based on the ADF/RAAF MOVCOORDC. It represented a novel approach in asset-management which incorporated planning for more than two days ahead, obtaining feed-back from the airframe operators in respect of which missions were not flown, and why being shot at constituted adequate reason for aborting a task, and actually involving the planning, operations and movements staff in further planning and decision-making.

For the statisticians, the following aircraft types and details may provide an insight into the variety of work being carried out by the UN air force in Cambodia; there were, in country, and based at U-Tapao (Thailand, near Pattaya), the following air assets:

Due to the variety of national military forces in country there were considerable differences in the way problems were approached ... from the 'get stuck in and have a go' style, to the 'if we ignore it, it will go away' approach. It took us nearly two months to be 'allowed' to trial an Air Movements Operations Coordination Centre (“AMOCC”, apt indeed!), which was based on the ADF/RAAF MOVCOORDC. It represented a novel approach in asset-management which incorporated planning for more than two days ahead, obtaining feed-back from the airframe operators in respect of which missions were not flown, and why being shot at constituted adequate reason for aborting a task, and actually involving the planning, operations and movements staff in further planning and decision-making.

For the statisticians, the following aircraft types and details may provide an insight into the variety of work being carried out by the UN air force in Cambodia; there were, in country, and based at U-Tapao (Thailand, near Pattaya), the following air assets:

•

6 x Puma helo (Fr.), 2 t. capable, 16 troops (30 if combat-loaded), based at Pochentong Air Base, Phnom Penh (PNP).

•

3 x C160 Transall (Fr.), less than C130 capability, with less range, also PNP-based.

•

3 x L100 series C130's, 1 from Transafrik, and 2 from Heavylift, with civilian crews, very professional, based at U- Tapao.

•

20 x MI-17 helos, 2 t. capable, internal or external, up to 40 pax combat-loaded, ex USSR Air Force (Afghanistan), based at PNP, several of which had been 'brassed-up' by the NADK, much to the (ex-USSR Air Force) crews' displeasure.

•

3 x RNlAF Fokker F27, 25 pax/5t., crewed very professionally by Dutch Air Force crews, based at UTP, where the Dutch had a large military presence.

•

1 x Beechcraft exec, 6 - 10 pax depending upon range requirement and runway capability, crewed by Danes, based at PNP for the use of the Mission director and other VIPs.

•

2 x MI-26 helos, 20t., internal or external, or 80-odd troops combat loaded [110 allegedly, if seriously combat loaded], leased from Aeroflot, operated by Aerolift/Heavilift, and crewed by Australians/Kiwis/Russians, based at PNP, who did an excellent job moving oversize/heavy stuff (like full TEUs) into areas inaccessible to fixed-wing.

The considerable air-lift capability in the region, with Pochentong Air Base, Phnom Penh, averaging 40 aircraft departures/turn-arounds/arrivals per day (daylight hours only, as there was no night-operations capability), was severely impeded by the paucity of material handling equipment and poor road transport infrastructure, and as a consequence, small problems often become major headaches very quickly.

UNTAC MCG Air Movements Ops Officers; Collie & Riddle (RAAF) & Froggat (Army) at Pochentong

Commercially contracted AN-12 operating [snrrrk!] in support of NGO

For the majority of the deployment, the Air Movements section at Pochentong consisted of two people, an RAAF Officer [and from him, more to come, later!] and SNCO, assisted by a French Air Force 'BOMAP' (air despatch) team, subordinated to HQMCG, who loaded the French aircraft and assisted when available with the other aircraft; naturally, there were only two of us who spoke any form of French (the author and FLTLT Collie), and only one of the BOMAP team was conversant in English ... but as we said, they had to work as hard to understand our French as we did to speak it!

As the wet season set in, in June, and as there were only four airfields in-country with fixed wing capability, the maximum use of helicopters became a priority, as surface transport access deteriorated.

As the wet season set in, in June, and as there were only four airfields in-country with fixed wing capability, the maximum use of helicopters became a priority, as surface transport access deteriorated.

French Pumas about to get wet

As I was to discover, the supply and allocation of administrative necessities in most UN Missions was not determined by the operational requirement for support, but more on the assumed status of the ‘requirer’, computers and communications assets being a case in point. From our arrival until well into the third month of our deployment we struggled to maintain reasonable comms and flight-following capability with the aircraft on daily taskings. Had it not been for the good relationships we formed with the Canadian contingent [PPLI 92éme Transport Coy] with whom we shared office space and resources, along with the Polish and Pakistani logistics elements, there would have been little ability to effect any change to the ‘developing nation’ mentality that pervaded the Mission.

Further, the parlous state of the Cambodian infrastructure after more than 20 years of destruction and neglect often worked against us.

Further, the parlous state of the Cambodian infrastructure after more than 20 years of destruction and neglect often worked against us.

‘Normal’ bridge

‘Normal’ bridge in the rain

The Netherlands Government provided 48 army personnel for MovCon duties, who arrived 4 July; unfortunately, only 12 were Movements trained (the balance were 'conscripts', some with only three months military service), and none of whom had any Air Movements / Transportation qualifications or expertise. We then had to instruct them 'on the job', and in order to encourage them to accept their responsibilities, we gained approval for our return home to be staggered, with an Advance Party (four pers) scheduled to depart 10 Aug, the Main Body (16 pers) on 17 Aug, and the Rear Party (10 pers) on 7 Sep '92.

The rear party comprised most of the AirOps people as this part of the transportation infrastructure was the most critical, and proved the most difficult for the Dutch to grasp. There was considerable reluctance to continue the administrative processes of booking personnel to flights (ie seat allocation) to ensure that there was no 'mad scramble' for seats when aircraft were scheduled to depart, and to raising of passenger and cargo manifests to identify who and what were on the aircraft, in the unfortunate event of crashes.

To further increase the enthusiasm for our replacements to learn, and assume responsibility for the operations and projects, we were advised that we had to take some of the UN leave we had accrued; a consequence of the 7-day-a-week ops was that we had not used any of the "Compensatory Time Off" days (6 days per month) that we were owed [unbeknown to us]; we were required to use 2-months worth, or lose it, and it could not be transferred to our National admin system. Thus, in the last week of July, and the first two weeks of August, most of the Australians took a week off, and went 'on hols' to either Pattaya, Bangkok, or in the case of O'Brien and Force, Hong Kong.

Movers’ other skills As well as the Movements and Transportation aspects of the Mission, we were also involved in the Logistics and Project Management, as transportation coordination was an integral part of all project tasks.

The rear party comprised most of the AirOps people as this part of the transportation infrastructure was the most critical, and proved the most difficult for the Dutch to grasp. There was considerable reluctance to continue the administrative processes of booking personnel to flights (ie seat allocation) to ensure that there was no 'mad scramble' for seats when aircraft were scheduled to depart, and to raising of passenger and cargo manifests to identify who and what were on the aircraft, in the unfortunate event of crashes.

To further increase the enthusiasm for our replacements to learn, and assume responsibility for the operations and projects, we were advised that we had to take some of the UN leave we had accrued; a consequence of the 7-day-a-week ops was that we had not used any of the "Compensatory Time Off" days (6 days per month) that we were owed [unbeknown to us]; we were required to use 2-months worth, or lose it, and it could not be transferred to our National admin system. Thus, in the last week of July, and the first two weeks of August, most of the Australians took a week off, and went 'on hols' to either Pattaya, Bangkok, or in the case of O'Brien and Force, Hong Kong.

Movers’ other skills As well as the Movements and Transportation aspects of the Mission, we were also involved in the Logistics and Project Management, as transportation coordination was an integral part of all project tasks.

But, we were instrumental in getting the railway running …

Three main projects were managed and coordinated to a smaller or larger degree by Australian Movement Control Group personnel, and the Canadian Logistics personnel; they were:

a.

"Operation Wishbone" - provision of foodstuffs and containers to the refugee and cantonment sites. The food encouraged the soldiers to give up their weapons, and the containers were used initially to transport and store the foodstuffs, then to secure the weapons. This operation was predominantly a Canadian/Australian effort, which commenced 11 Jun, and continued throughout the duration of the deployment.

b.

"Operation Mercury" - provision of generators to provincial headquarters and other necessary sites. The generators ranged from small, man-portable, to large, 2,000lb air-portable, town power generation units. Again, predominantly Canadian/Australian, military and civilian personnel. This operation commenced 18 Jun, and had not been completed by the time we left mid-Sep.

c.

"Operation Locktite" - provision of portable buildings and camp-complexes for use by UN personnel and administrative infrastructure rebuilding, throughout the country. Comprising Canadian and Australian military personnel and several contracted civilian companies, notably "WeatherHaven" from Canada, and "MSD" and "Ausco" from Australia, this operation, like "Mercury", commenced on 18 Jun, and had not been completed by the time we left.

" Wishbone" UN251 Mi-26 Flat-floor 15t rice, 2t tin fish, 2t veg oil

On a cultural note, the author was requested by the Australian Diplomatic Mission to assist with the transportation to Australia by RAAF C130 and QANTAS of the "Age of Angkor" Khmer antiquities exhibition being mounted by the Australian National Gallery. These national treasures were packaged by an Australian company, at the Phnom Penh Museum of Fine Arts, then transported by RAAF C130 to Bangkok, where they were trans-shipped to a QANTAS 747 for the voyage to Australia (the process was reversed in November for the return voyage).

The RAAF MCG personnel were all involved in this project in some form or other, and although not strictly UNTAC-related, the successful completion of the task reflected further credit on the Australian movements personnel. Two RAAF C130 flights were involved in this task and gave us the opportunity to work with some professionals for a couple of hours on the days that they were in Phnom Penh (23 Jun and 22 Jul). These two flights were also used to convey stores and mail to the ANZAC Contingent in UNTAC, and we were probably the most sought after Australians in Cambodia on those two days, more than normally so because of our transport assets' attractiveness.

The arrival of the first C130 was much awaited by us, as we knew that it would bring 'care-packages' from home ... and it would be well worth building pallets in the heat and humidity (about 35ºC and 85-90% humidity by midday).

The RAAF MCG personnel were all involved in this project in some form or other, and although not strictly UNTAC-related, the successful completion of the task reflected further credit on the Australian movements personnel. Two RAAF C130 flights were involved in this task and gave us the opportunity to work with some professionals for a couple of hours on the days that they were in Phnom Penh (23 Jun and 22 Jul). These two flights were also used to convey stores and mail to the ANZAC Contingent in UNTAC, and we were probably the most sought after Australians in Cambodia on those two days, more than normally so because of our transport assets' attractiveness.

The arrival of the first C130 was much awaited by us, as we knew that it would bring 'care-packages' from home ... and it would be well worth building pallets in the heat and humidity (about 35ºC and 85-90% humidity by midday).

RAAF C130 A97-001 “BU-601” at Pochentong to collect the “Age of Angkor” artefacts

The involvement in the “Age of Angkor” task supplemented our rather fragile link with home, which for the first six weeks was via post only, which generally took about two weeks from mailing to receipt; phone communications outside the military comms nets was tenuous for the first couple of months, until the military and commercial contractors were able to rebuild the civilian, mostly mobile, telephone system.

Less work

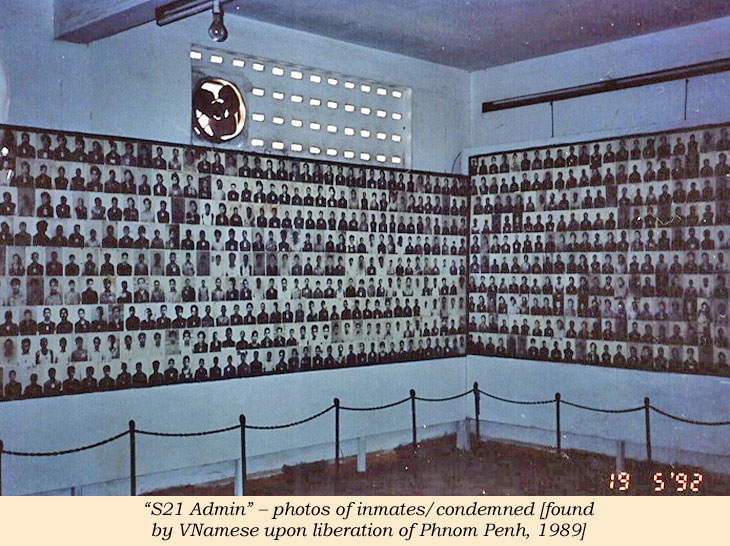

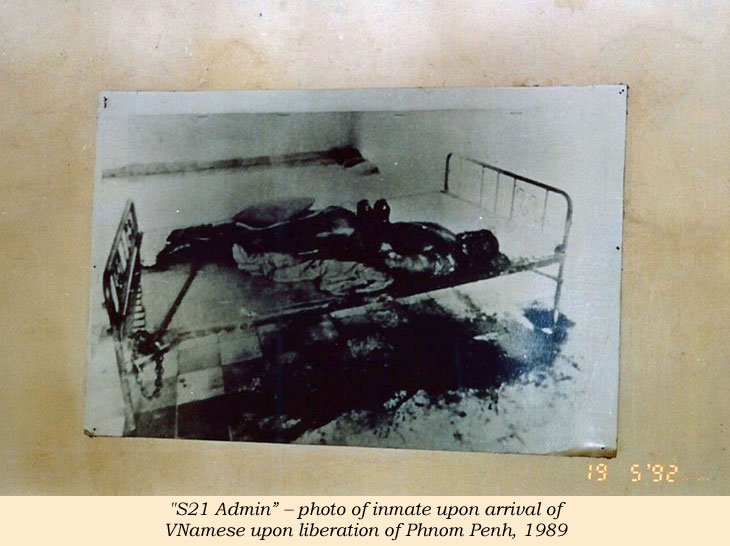

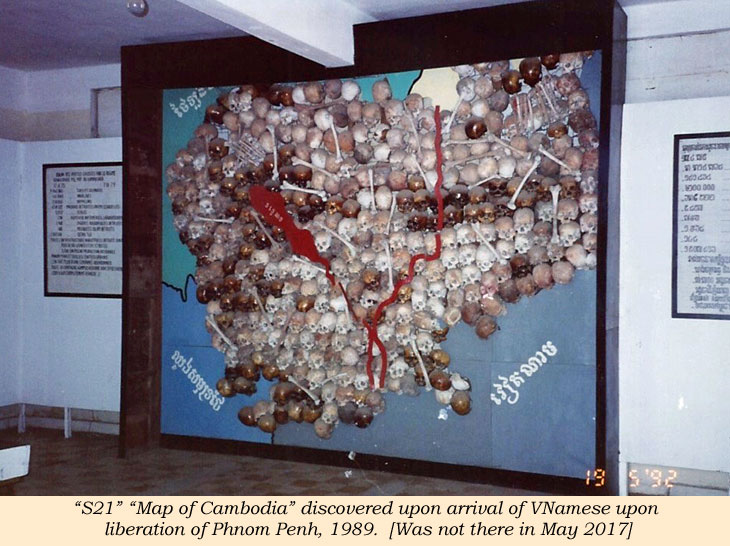

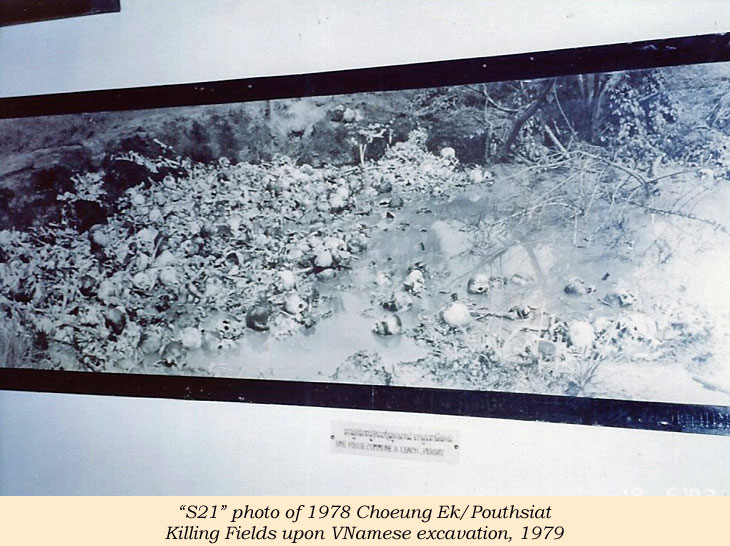

Of note, we were not blind to the depredations of Cambodia’s previous rulers and pretenders, and took the opportunity to absorb the evidence of the most recent, Pol Pot. The Tuol Sleng/S21 Prison, previously a school, now a museum to four years of horror, was certainly an example of man’s inhumanity. Most of the photographic evidence presented was as documented by the Khmer Rouge themselves, and rescued by the Vietnamese authorities upon their expulsion of Pol Pot’s administration in 1979

Less work

Of note, we were not blind to the depredations of Cambodia’s previous rulers and pretenders, and took the opportunity to absorb the evidence of the most recent, Pol Pot. The Tuol Sleng/S21 Prison, previously a school, now a museum to four years of horror, was certainly an example of man’s inhumanity. Most of the photographic evidence presented was as documented by the Khmer Rouge themselves, and rescued by the Vietnamese authorities upon their expulsion of Pol Pot’s administration in 1979

Notwithstanding the horrors of the Killing Fields and the indiscriminate sowing of land-mines throughout the country, the magnificence and grandeur of the 12th/13th Century Bayon/Angkor complexes was overwhelming; yet there were moments when our up-country MovDet personnel must have questioned our raison d’être, as they were often called upon to be ‘tour guides’. And, alas it is in more recent times that as the area has been successfully cleared of landmines, it has opened up for the modern blight: tourism. Perhaps the intervention of UNESCO and other worthy archaeological organisations will ensure its’ longevity.

Conclusion That the UN’s Elections were held in May ’93, in relative security and peace is in no small part a testament to the efforts of the Australian Movement Control Group personnel, whose adaptability and enthusiasm ensured the best results from the multi- modal transport assets available, in spite of the ‘dog in the manger’ attitude of many of the Mission Contributors’; in particular the RAAF Members, who were able to bludgeon their Air Movements skills into the daily operations, were of primary importance. Those skills and doctrinal inputs are evident in current Peacekeeping Missions, some of which now have ex-MCG UNTAC personnel in executive appointments.

Conclusion That the UN’s Elections were held in May ’93, in relative security and peace is in no small part a testament to the efforts of the Australian Movement Control Group personnel, whose adaptability and enthusiasm ensured the best results from the multi- modal transport assets available, in spite of the ‘dog in the manger’ attitude of many of the Mission Contributors’; in particular the RAAF Members, who were able to bludgeon their Air Movements skills into the daily operations, were of primary importance. Those skills and doctrinal inputs are evident in current Peacekeeping Missions, some of which now have ex-MCG UNTAC personnel in executive appointments.

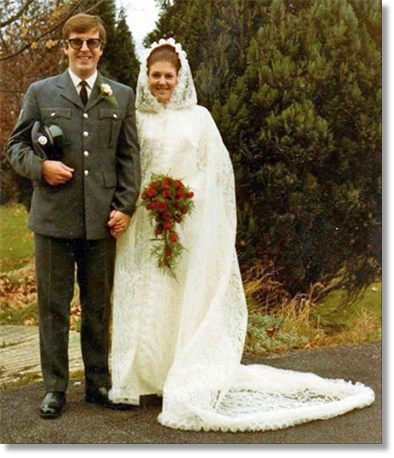

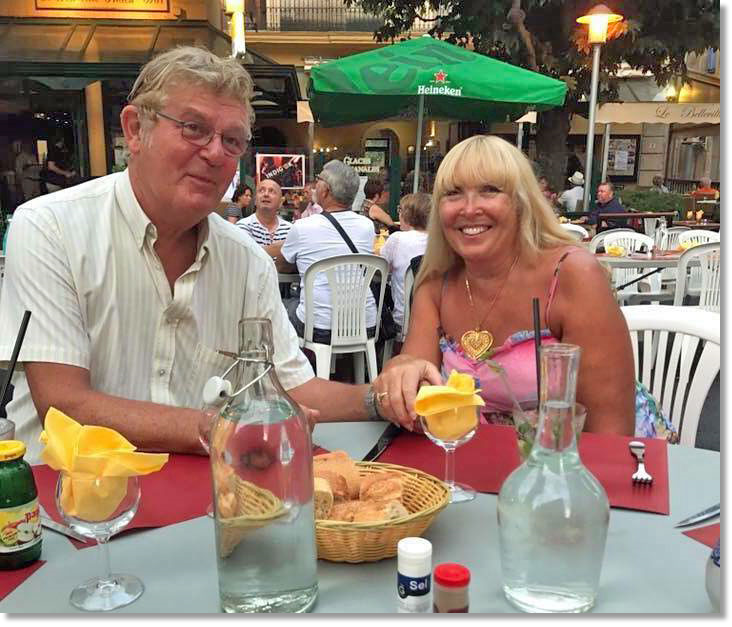

The Author and Neil Collie took our partners to Cambodia during May of 2017, as a 25th Anniversary of our deployment commemorative visit, and we were overwhelmed by the growth and commercialization of almost every aspect of the country's past.

Tactical Grey is the New Yellow

For Canada's search-and-rescue planes, 'tactical grey' is the new yellow. That could mean they're heading to combat

Canada’s new search-and-rescue aircraft will abandon their familiar yellow paint scheme, instead getting a makeover that will allow them to be used in other missions, including combat.

The Royal Canadian Air Force has requested that its new fleet of 16 search-and-rescue planes be painted tactical grey and have asked for a change in the original contract which stipulated a yellow colour scheme.

The C-295W, being built by Airbus, will replace the main search-and-rescue fleet of six Buffalo aircraft as well as the Hercules transport planes which are also used at times in a search-and-rescue role. The Buffalos are painted yellow, as are Canada’s other fully dedicated search-and-rescue aircraft such as the Cormorant helicopters.

“The RCAF has made the decision to use a grey colour scheme for the C-295W fleet to enable surging flexibility for the very wide range of missions the RCAF is required to conduct, from humanitarian and disaster relief missions, to security missions with partners, and all the way to full spectrum operations,” Department of National Defence spokesman Daniel Le Bouthillier said Thursday.

National Post

Canada’s new search-and-rescue aircraft will abandon their familiar yellow paint scheme, instead getting a makeover that will allow them to be used in other missions, including combat.

The Royal Canadian Air Force has requested that its new fleet of 16 search-and-rescue planes be painted tactical grey and have asked for a change in the original contract which stipulated a yellow colour scheme.

The C-295W, being built by Airbus, will replace the main search-and-rescue fleet of six Buffalo aircraft as well as the Hercules transport planes which are also used at times in a search-and-rescue role. The Buffalos are painted yellow, as are Canada’s other fully dedicated search-and-rescue aircraft such as the Cormorant helicopters.

“The RCAF has made the decision to use a grey colour scheme for the C-295W fleet to enable surging flexibility for the very wide range of missions the RCAF is required to conduct, from humanitarian and disaster relief missions, to security missions with partners, and all the way to full spectrum operations,” Department of National Defence spokesman Daniel Le Bouthillier said Thursday.

National Post

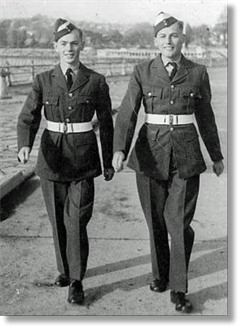

From: Douglas Stewart, Stouffville, ON

Subject: Membership Application

Hi Tony,

Thanks for your response to my Membership Application and the additional info you sent re your organization.

I guess I served in Air Movements during my time in the RAF, although I don't recall that exact term. Suffice to say that it involved ordering and distributing supplies. At the small stations, including Salalah, it also involved loading and unloading aircraft, only one a week, and generally running the "Stores". Prior to Salalah, I spent about 8 months at Khormaksar in Aden.

Later in my service I was posted to Shallufa in Egypt (Canal Zone) before spending a short time in Palestine, then returning home in 1948.

All seems long ago now, but I still have old b/w photos of those days. Salalah, above all, left a lasting impression on me that has remained the rest of my life; it was a million miles from my working class background in London, while growing up.

I recently turned age 90. Looking back, I would not have missed the experience.

Regards,

Doug Stewart

Subject: Membership Application

Hi Tony,

Thanks for your response to my Membership Application and the additional info you sent re your organization.

I guess I served in Air Movements during my time in the RAF, although I don't recall that exact term. Suffice to say that it involved ordering and distributing supplies. At the small stations, including Salalah, it also involved loading and unloading aircraft, only one a week, and generally running the "Stores". Prior to Salalah, I spent about 8 months at Khormaksar in Aden.

Later in my service I was posted to Shallufa in Egypt (Canal Zone) before spending a short time in Palestine, then returning home in 1948.

All seems long ago now, but I still have old b/w photos of those days. Salalah, above all, left a lasting impression on me that has remained the rest of my life; it was a million miles from my working class background in London, while growing up.

I recently turned age 90. Looking back, I would not have missed the experience.

Regards,

Doug Stewart

How to get a five-tonne snowblower to the Arctic

The fire truck and snowblower, pictured in Thule, Greenland. The ropes and wires attached ensured they hardly jiggled in the Globemaster plane. JOHN HODERICH / TORONTO STAR

When Canada provides aid to typhoon-stricken Philippines and gets there before anyone else, who does it? Or brings our renowned water-purification team plus helicopter to earthquake-ravaged Nepal? Or brings supplies to Canadian troops in Afghanistan? Or brings hurricane relief to devastated Texas? Or, on a more mundane level, brings a new fire truck and snowblower to the northernmost settlement on the planet? The answer to all? The 429 Transport Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The 429 members aren’t the ones you see in action in areas of mass destruction. Rather, they are the unsung heroes whose sole job is to get the transportation part done — quickly and efficiently. Based in Trenton, Ont., their theatre is the world. They are ready to go whenever the need arrives and usually on very short notice. And they’re always prepared for “snags” — militarese for malfunctions and screw-ups. They go with the job, or as Sgt. Patryk Wegrzyn told me “a chance for us to really prove ourselves.”

For four days, I had the opportunity to watch one crew up close as they delivered that fire truck and snowblower to Alert, Nunavut, on the northernmost tip of Ellesmere Island. I was officially checked in as part of the crew, though insisting on paying my own expenses and accommodation. I would be with them from the usual breakfast at 6 a.m. until the “social” at night which, by rule, shut down completely 12 hours before next takeoff.

The 429 members aren’t the ones you see in action in areas of mass destruction. Rather, they are the unsung heroes whose sole job is to get the transportation part done — quickly and efficiently. Based in Trenton, Ont., their theatre is the world. They are ready to go whenever the need arrives and usually on very short notice. And they’re always prepared for “snags” — militarese for malfunctions and screw-ups. They go with the job, or as Sgt. Patryk Wegrzyn told me “a chance for us to really prove ourselves.”

For four days, I had the opportunity to watch one crew up close as they delivered that fire truck and snowblower to Alert, Nunavut, on the northernmost tip of Ellesmere Island. I was officially checked in as part of the crew, though insisting on paying my own expenses and accommodation. I would be with them from the usual breakfast at 6 a.m. until the “social” at night which, by rule, shut down completely 12 hours before next takeoff.

The task ahead was one of the squadron’s regular jobs: Operation BOXTOP. Keep the military’s most northern outpost serviced and supplied. Hence the lime-coloured fire truck. The old one got smashed in an icy pileup. The journey began on a Monday at 5:30 a.m. We gathered at CFB Trenton for the short van ride to the giant Globemaster aircraft. Capt. Sean Bassett, a no-nonsense, thoroughly professional leader, laid out the mission in staccato tones: Deliver the goods to Alert, drop off some people and attempt five “chalks” (trips) with fuel from Thule Air Base in Greenland to Alert. But he warned weather could be a big factor. To the rest of the seven-person crew, this seemed like business as usual.

CFB Trenton prides itself as being “the hub of air mobility.” As I was told often, “if you want boots on the ground, this is where you start.” And the huge CC-177 Globemaster III is the workhorse for the squadron. It is a beast. Each of its four jet engines has 18,343 kilograms of thrust. It is almost 17 metres high inside, can carry 110,676 kilograms of fuel and has a range of 10,186 kilometres. Our first destination was Thule, the sprawling U.S. air force base three-quarters the way up the west coast of Greenland. Situated 1,200 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, it provides an ideal refuelling stop for the Globemasters en route to Alert. Yet there is a catch. You can only land between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., Monday to Friday. All weekend it is shut. It seems the Americans have outsourced management of the base to local Greenlanders and they operate the base on old banking hours. God forbid anything untoward happens on weekends. This turned out to be a big factor on our mission.

The task of loading the Globemaster with the fire truck, the snowblower and all the other food and goods is the responsibility of the loadmaster. Our loadmaster was Sgt. Marie-Pierre Tremblay, as direct, plain spoken and confident as you can imagine. “I love my job. I have a real passion for it,” she told me right up front. “And I’m very good at it.”

The total weight of our cargo was 34,473 kilograms, and it was her responsibility to make sure it was distributed evenly for takeoff, securely tied down and kept perfectly intact. “This is a real science,” explained Wegrzyn, who was along to do the annual “flight check” of his colleague Tremblay. “You have to make sure everything is put in exactly the right place.”

My pull-down seat on the fuselage of the Globemaster was beside the fire truck, to which I became quite attached. I can assure you it hardly jiggled the entire trip. And the ropes and guy wires holding it in place were checked regularly by Tremblay and her trainee, Master Cpl. James Brown. It turned out landing in Thule was no problem, and so our first leg was completed as planned.

Then I got my first Arctic lesson. “Make sure you bring your bag back here every day,” co-pilot Maj. Pierre-Luc Verreault told me. “You never know where we might be forced to land. Goose Bay, Fro Bay (Iqaluit) or wherever!” My second lesson came as we checked into the North Star Inn on the base. The hardbitten clerk warned us the winds were becoming so strong there might be a “lockdown.” That meant no one could leave the building.

The North Star is a military-style hotel — shared washroom and showers, with men on the second floor and women on the first. Despite the lockdown threat, we were able to head out to the mess for dinner, walking past a cluster of arctic foxes or “archies” as the locals call them. At $5.07, the price for dinner was a bargain and the food was surprisingly good. But not a drop of alcohol was to be found.

CFB Trenton prides itself as being “the hub of air mobility.” As I was told often, “if you want boots on the ground, this is where you start.” And the huge CC-177 Globemaster III is the workhorse for the squadron. It is a beast. Each of its four jet engines has 18,343 kilograms of thrust. It is almost 17 metres high inside, can carry 110,676 kilograms of fuel and has a range of 10,186 kilometres. Our first destination was Thule, the sprawling U.S. air force base three-quarters the way up the west coast of Greenland. Situated 1,200 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, it provides an ideal refuelling stop for the Globemasters en route to Alert. Yet there is a catch. You can only land between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., Monday to Friday. All weekend it is shut. It seems the Americans have outsourced management of the base to local Greenlanders and they operate the base on old banking hours. God forbid anything untoward happens on weekends. This turned out to be a big factor on our mission.

The task of loading the Globemaster with the fire truck, the snowblower and all the other food and goods is the responsibility of the loadmaster. Our loadmaster was Sgt. Marie-Pierre Tremblay, as direct, plain spoken and confident as you can imagine. “I love my job. I have a real passion for it,” she told me right up front. “And I’m very good at it.”

The total weight of our cargo was 34,473 kilograms, and it was her responsibility to make sure it was distributed evenly for takeoff, securely tied down and kept perfectly intact. “This is a real science,” explained Wegrzyn, who was along to do the annual “flight check” of his colleague Tremblay. “You have to make sure everything is put in exactly the right place.”

My pull-down seat on the fuselage of the Globemaster was beside the fire truck, to which I became quite attached. I can assure you it hardly jiggled the entire trip. And the ropes and guy wires holding it in place were checked regularly by Tremblay and her trainee, Master Cpl. James Brown. It turned out landing in Thule was no problem, and so our first leg was completed as planned.

Then I got my first Arctic lesson. “Make sure you bring your bag back here every day,” co-pilot Maj. Pierre-Luc Verreault told me. “You never know where we might be forced to land. Goose Bay, Fro Bay (Iqaluit) or wherever!” My second lesson came as we checked into the North Star Inn on the base. The hardbitten clerk warned us the winds were becoming so strong there might be a “lockdown.” That meant no one could leave the building.

The North Star is a military-style hotel — shared washroom and showers, with men on the second floor and women on the first. Despite the lockdown threat, we were able to head out to the mess for dinner, walking past a cluster of arctic foxes or “archies” as the locals call them. At $5.07, the price for dinner was a bargain and the food was surprisingly good. But not a drop of alcohol was to be found.

The following morning, we gathered at 5 a.m. for a $2.03 breakfast, all eager to get going. But as the pilots went through their checklists, they discovered one of the electronic boxes in the cockpit wasn’t working. Now what? We couldn’t take off and the talk was of having Trenton fly up a new box, forcing us, of course, to wait. Would it be one day? Would it be two?

Then suddenly the machinist of the crew, Cpl. Don Gunawardena, remembered there was a spare container of Globemaster parts in one of the hangars. He and his delightful mate, electrician Master Cpl. Mike Gagne, rummaged through as we all watched. And voila, they found a spare box! In no time flat it was installed and we were off to Alert. We travelled over the spectacular Quttinirpaaq National Park, catching sight of Barbeau Peak, the highest mountain in Eastern Canada. By now it was midday and the light was as good as a late October could offer.

Landing at Alert is a challenge, whenever. At 1,676 metres, the gravel runway offers precious little room for error. For most of the year, the runway is ice-slick and as pilot Bassett told us, “planes can slide just like cars.” It seems the reverse engine thrusters do most of the stopping. The approach comes from right over the Arctic Ocean and buffeting crosswinds are the norm. The ceiling has to be 152 metres, and as we experienced, that can vary from minute to minute. There is a “box” at the start of the runway in which the pilots know they have to land to guarantee room to stop.

In the cockpit, the tension is palpable as the approach is made. In the dark gloom, the only light comes from the runway lights, which can be turned way up. I saw each pilot do this landing and as one might expect, each nailed it. But both times, it was an exercise in aviation precision to behold.

Once on the ground, all the crates and boxes were swiftly unloaded. The real challenge came with the nearly five-tonne snowblower, which was on its own pallet. It wouldn’t budge. The entire crew, plus a few hands from Alert, had to lend a strong shoulder. Then the moment of satisfaction came. The fire engine driver from Alert turned the key, and with red lights blaring, drove the truck from the Globemaster onto the icy gravel tarmac in minus-23 degree weather. Mission accomplished. There were no high-fives or unusual remarks, only the collective quiet satisfaction of getting the job done. They’d all experienced this before.

Shortly thereafter, we took off for Thule. The plan had been to do another “chalk” to Alert with fuel that afternoon. But the time spent earlier on repairs meant we couldn’t do a return trip and make the 4 p.m. closing time at Thule. So, we got off early.

The drill repeated itself the following day and we took off, loaded with fuel. This time the cloud ceiling at Alert wouldn’t allow a landing, so we were forced to circle for quite some time. Suddenly we got a break, and with crosswinds howling, co-pilot Verreault strutted his stuff. The fuel was pumped out quickly, but once again, a second planned fuel trip had to be scrubbed for we couldn’t guarantee making Thule’s 4 p.m. closing time. Again, no one seemed bothered. After all, this is the Arctic. On the way back, however, the pilots discovered a de-icing problem with engine No. 4. A valve was malfunctioning and despite all their manoeuvres, they couldn’t get it to operate properly.

Then suddenly the machinist of the crew, Cpl. Don Gunawardena, remembered there was a spare container of Globemaster parts in one of the hangars. He and his delightful mate, electrician Master Cpl. Mike Gagne, rummaged through as we all watched. And voila, they found a spare box! In no time flat it was installed and we were off to Alert. We travelled over the spectacular Quttinirpaaq National Park, catching sight of Barbeau Peak, the highest mountain in Eastern Canada. By now it was midday and the light was as good as a late October could offer.

Landing at Alert is a challenge, whenever. At 1,676 metres, the gravel runway offers precious little room for error. For most of the year, the runway is ice-slick and as pilot Bassett told us, “planes can slide just like cars.” It seems the reverse engine thrusters do most of the stopping. The approach comes from right over the Arctic Ocean and buffeting crosswinds are the norm. The ceiling has to be 152 metres, and as we experienced, that can vary from minute to minute. There is a “box” at the start of the runway in which the pilots know they have to land to guarantee room to stop.

In the cockpit, the tension is palpable as the approach is made. In the dark gloom, the only light comes from the runway lights, which can be turned way up. I saw each pilot do this landing and as one might expect, each nailed it. But both times, it was an exercise in aviation precision to behold.

Once on the ground, all the crates and boxes were swiftly unloaded. The real challenge came with the nearly five-tonne snowblower, which was on its own pallet. It wouldn’t budge. The entire crew, plus a few hands from Alert, had to lend a strong shoulder. Then the moment of satisfaction came. The fire engine driver from Alert turned the key, and with red lights blaring, drove the truck from the Globemaster onto the icy gravel tarmac in minus-23 degree weather. Mission accomplished. There were no high-fives or unusual remarks, only the collective quiet satisfaction of getting the job done. They’d all experienced this before.

Shortly thereafter, we took off for Thule. The plan had been to do another “chalk” to Alert with fuel that afternoon. But the time spent earlier on repairs meant we couldn’t do a return trip and make the 4 p.m. closing time at Thule. So, we got off early.

The drill repeated itself the following day and we took off, loaded with fuel. This time the cloud ceiling at Alert wouldn’t allow a landing, so we were forced to circle for quite some time. Suddenly we got a break, and with crosswinds howling, co-pilot Verreault strutted his stuff. The fuel was pumped out quickly, but once again, a second planned fuel trip had to be scrubbed for we couldn’t guarantee making Thule’s 4 p.m. closing time. Again, no one seemed bothered. After all, this is the Arctic. On the way back, however, the pilots discovered a de-icing problem with engine No. 4. A valve was malfunctioning and despite all their manoeuvres, they couldn’t get it to operate properly.