During late July of 1990 Saddam Hussein, the president of Iraq, built up his military forces on the border with Kuwait.

At 1:00 a.m. on 02 August 1990, three Iraqi divisions of the elite Republican Guard rolled over the border. Resistance was nearly non-existent. The Guard reached the outskirts of the capital, Kuwait City, a mere four and a half hours later. The frontal assault was supported by an airborne special forces division attack directly on Kuwait City itself.

Saddam proclaimed his annexation of Kuwait, built up his forces, and waited to see what the world would say and do about his fait accompli.

At 1:00 a.m. on 02 August 1990, three Iraqi divisions of the elite Republican Guard rolled over the border. Resistance was nearly non-existent. The Guard reached the outskirts of the capital, Kuwait City, a mere four and a half hours later. The frontal assault was supported by an airborne special forces division attack directly on Kuwait City itself.

Saddam proclaimed his annexation of Kuwait, built up his forces, and waited to see what the world would say and do about his fait accompli.

On entering and effectively dominating Kuwait, the Iraqi forces immediately moved south and positioned themselves opposite the lightly defended oilfields of Saudi Arabia. This was seen as a statement of aggressive intent and the Saudis requested help from the United States. The Americans deployed elements of the 82nd Airborne Division as a deterrent against further Iraqi advancement.

The Iraqis stopped short of Saudi Arabia and dug themselves in along the border . The Americans built up their forces while the Iraqis continued to consolidate their positions. The United Nations quickly imposed economic sanctions whilst he US sought support from its NATO allies for more tangible military aid.

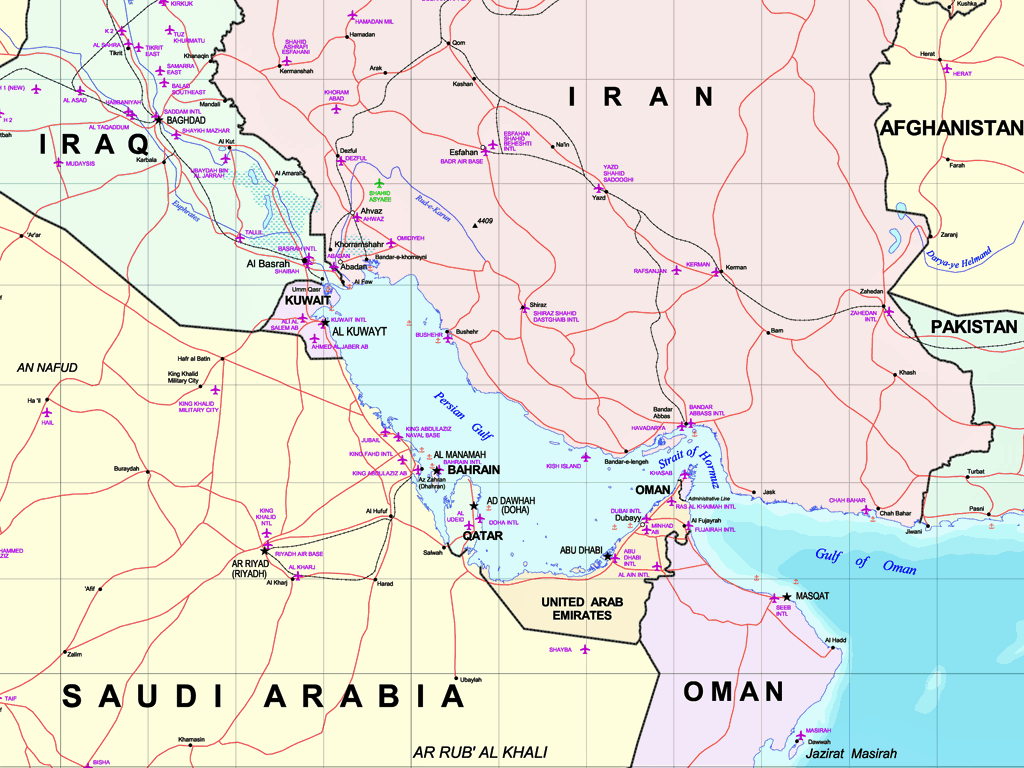

The British Government were the first to respond and ordered the deployment of Jaguar aircraft to Thumrait (Oman) and the Tornado aircraft to Saudi Arabia. This deployment signaled the start of Operation Granby.

UKMAMS were involved from the outset, establishing a Forward Mounting Base (FMB) at RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus, and two Forward Operating Bases (FOB's); one in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and the other in Thumrait, Oman...

The British Government were the first to respond and ordered the deployment of Jaguar aircraft to Thumrait (Oman) and the Tornado aircraft to Saudi Arabia. This deployment signaled the start of Operation Granby.

UKMAMS were involved from the outset, establishing a Forward Mounting Base (FMB) at RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus, and two Forward Operating Bases (FOB's); one in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and the other in Thumrait, Oman...

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On 9th August, 1990, 5 full UKMAMS teams, complete with engineering support and field equipment, deployed to RAF Akrotiri to await confirmation of the final locations of the FOB's. The plan was to keep two teams at Akrotiri to reinforce the resident movements squadron, and send three teams forward to man the FOB's.

The first flying squadron to deploy was a Tornado squadron which was on exercise in Cyprus at the outbreak of hostilities. As planned, two teams assisted with the preparation of ground support equipment into chalk loads whilst the other three teams were to go forward to Dhahran. The first team departed Cyprus for Dhahran, taking with them sufficient equipment for 72 hours of unsupported operations, which included full nuclear, biological and chemical warfare protection gear. The other two teams arrived the next day. Within two days the first Tornado squadron was fully deployed in-theatre.

The first flying squadron to deploy was a Tornado squadron which was on exercise in Cyprus at the outbreak of hostilities. As planned, two teams assisted with the preparation of ground support equipment into chalk loads whilst the other three teams were to go forward to Dhahran. The first team departed Cyprus for Dhahran, taking with them sufficient equipment for 72 hours of unsupported operations, which included full nuclear, biological and chemical warfare protection gear. The other two teams arrived the next day. Within two days the first Tornado squadron was fully deployed in-theatre.

On 12th August the decision was taken to deploy 6 Squadron (Jaguars) from RAF Colitshall to the 2nd FOB at Thumrait. A team was deployed from Lyneham to Coltishall to assist the station mobility personnel in the preparation and loading of the squadron to transport aircraft. In the meantime, two UKMAMS teams were deployed to Thumrait to establish an airhead and prepare for the reception of the Jaguars. A third UKMAMS team was deployed from Akrotiri.

The Thumrait detachment were kept on constant alert for fear of a Yemeni attack, as the Yemenis became progressively more pro-Iraq. The teams were also denied any form of accommodation and had only limited access to an international telephone. The reception of the Jaguars proceeded on schedule despite a multitude of problems. The aircraft handling area was very small and inevitably it was very congested. A USAF Aerial Port Squadron helped enormously with the loan of equipment and facilities. After three days, a mobile catering support unit was deployed from the UK and for the first time the teams were able to enjoy well prepared nourishment. The positioning of the Jaguars at Thumrait was by and large a political move and negotiations were under way to move them closer to Kuwait. The logical place for the Jaguars would be Bahrain, an independent archipelago of islands halfway up the Arabian Gulf.

The Thumrait detachment were kept on constant alert for fear of a Yemeni attack, as the Yemenis became progressively more pro-Iraq. The teams were also denied any form of accommodation and had only limited access to an international telephone. The reception of the Jaguars proceeded on schedule despite a multitude of problems. The aircraft handling area was very small and inevitably it was very congested. A USAF Aerial Port Squadron helped enormously with the loan of equipment and facilities. After three days, a mobile catering support unit was deployed from the UK and for the first time the teams were able to enjoy well prepared nourishment. The positioning of the Jaguars at Thumrait was by and large a political move and negotiations were under way to move them closer to Kuwait. The logical place for the Jaguars would be Bahrain, an independent archipelago of islands halfway up the Arabian Gulf.

Bahrain has an enviable history that includes the acquisition of a former British military airport, Muharraq. There was also an RAF presence in the shape of a flight lieutenant movements liaison officer (RAFLO), normally ex-UKMAMS the current officer was Richard "Foggy" Fogden. A MAMS team were positioned in Bahrain on 26th August 1990 to see in a Tornado squadron. The team consisted of 18 men and so were able to work two shifts giving 24 hours coverage. Whist the MAMS detachment had a limited quantity of its own handling equipment and given the enormous volume of military stores pouring in, they were heavily reliant on Gulf Air and the Bahrain Airport Services to assist in the offloading of our aircraft.

On a more domestic note, the team were housed in an air conditioned hut on the edge of the pan and when they were not working they were housed in the Bahrain Hilton Hotel.

On a more domestic note, the team were housed in an air conditioned hut on the edge of the pan and when they were not working they were housed in the Bahrain Hilton Hotel.

The inbound aircraft loads of Tornado equipment started to arrive on 26th August at such a rate that a reinforcement of 6 personnel from Lyneham had to be flown in. The operation went on continuously for 48 hours while the Tornado squadron personnel worked diligently to sort out the supplies and clear up the backlog from the arrival area. By 6th September the bulk of the Tornado equipment was in position and the workload was reduced sufficiently so that a 6 man MAMS team was all that was required in Bahrain to handle the re-supply aircraft.

Further down the Arabian Gulf another UKMAMS detachment was deployed to an airfield at Seeb in Muscat. The team were there to receive the three Nimrod maritime reconnaissance aircraft and four VC-10 in-flight refueling tankers that were assigned to that base. Once in position with all of their ground equipment the team remained there to handle the aircraft ground crew rotation and spares resupply. Living and working conditions were relatively good at Seeb. The MAMS detachment commander had access to the Nimrod Operations Centre which was very well furnished with communications equipment, including a fax machine which had the added advantage of being secure.

Further down the Arabian Gulf another UKMAMS detachment was deployed to an airfield at Seeb in Muscat. The team were there to receive the three Nimrod maritime reconnaissance aircraft and four VC-10 in-flight refueling tankers that were assigned to that base. Once in position with all of their ground equipment the team remained there to handle the aircraft ground crew rotation and spares resupply. Living and working conditions were relatively good at Seeb. The MAMS detachment commander had access to the Nimrod Operations Centre which was very well furnished with communications equipment, including a fax machine which had the added advantage of being secure.

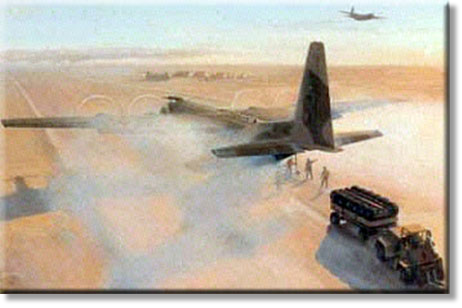

The working conditions were appalling. The teams, working in temperatures of plus 40ºC handled both C-130 and VC-10 aircraft mainly by hand owing to a shortage of the requisite handling aids and aircraft role equipment. Once this initial deployment was complete, two teams were returned to Cyprus to await further tasking. The remaining team found working space in the offices of the Royal Saudi Air Force and domestic succour in the British Aerospace compound in the nearby town of Al Khobar.

Seeb is blessed with a number of quite excellent hotels and in due course the Hercules crews became aware of this and persuaded HQ Strike Command that this was the place to "slip". On long flights, where crews cannot be expected to complete the whole trip at one time, there are two options; firstly you can night stop the whole flight to rest the crew, or secondly you can speed things up by pre-positioning a fresh crew to take the flight over - this latter practice is known as "slipping". The task of managing the slip crews fell to the resident MAMS team leader.

Another UKMAMS team was deployed to the United Arab Emirates in support of the resupply of Royal Navy ships that were using the ports of Jebel Ali and Rashid. Rather than using the rather plush facilities at Dubai International Airport, the resupply aircraft were tasked into the military fighter base at Minhad, some 50 kilometres from the ports. Minhad was not ideally suited to the reception of transport aircraft and there were no facilities for larges volumes of inbound freight. A four man MAMS team were initially deployed to handle the inbound freighters and the local military worked in coercion with them, providing trucks and drivers as required. Elements of the USAF arrived soon after, bringing with them all of the required freight handling equipment, to be followed very closely by Royal Navy store men which took the pressure off of the MAMS team. The freighter aircrews began slipping at Minhad which now fell under MAMS managerial responsibility, while they had the added task of logistical support for a rather large Army exercise in the area.

Meanwhile, back in the UK, the movements staff at Lyneham were placed on a three shift system in order to free up the fourth shift for reinforcement of the mobile MAMS teams. Many of the various combat units despatched to the Gulf had previously been prepared and loaded by the re-employed shift personnel and not the regular MAMS teams. These contingency teams spent a particularly hard two months moving around the UK and Germany loading out flying squadrons and their support equipment to their predetermined Gulf locations.

On one such task, at Coltishall, the MAMS team worked solidly for 36 hours with only a 30 minute tea break midway through the flow. Straight after this, the team (all from C Shift) were immediately sent to RAF Honington where they deployed RAF Regiment personnel and their Rapier AA equipment to the Gulf. Movements staff at this time were so hard pressed that the movements auxiliaries of No. 4624 Squadron were brought in to lend a hand on weekends. By the end of the initial deployment, the teams had loaded over 320 Hercules sorties from Coltishall, Honington, Leuchars, Wittering, Wyton, Kinloss, Coningsby and Bruggen.

All flights en-route to the Gulf were staged through RAF Akrotiri - an additional 35 movements personnel were drafted into Akrotiri and this became a major point of contention as the aircraft were already fully loaded and didn't require any movements input apart from the normal in-transit handling procedure.

By the end of September, the initial forces of the alliance were deployed and ready to defend against possible Iraqi aggression, which whilst unlikely couldn't be ruled out. The United Nations made repeated calls on the Iraqis to leave Kuwait, but the Iraqis no longer recognized Kuwait as an independent state so they chose not to. Sanctions were imposed on the Iraqis and the prospect of war seemed more and more likely. The Iraqis were playing a waiting game for good reason. The alliance of Arab Islamic states with the two Great Satans (the British and the Americans) against a brother Arab state was alarming to say the least and Iraq was hoping for both Arab and domestic Western opinion to turn against the prospect of war which would produce no tangible benefit to themselves. This proved to be a huge miscalculation and allowed the British to deploy more Tornado aircraft and 7 Armoured Brigade to the Saudi desert. This of course was to greatly increase the workload of UKMAMS.

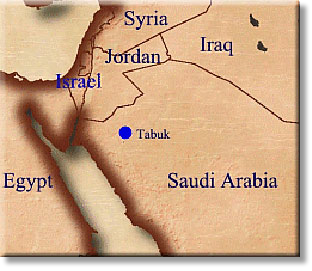

In late September a reconnaissance team went to the desert airbase at Tabuk. It was deemed unsuitable for our operations owing to poor sanitary conditions, non- existent aircraft handling equipment and unsatisfactory accommodations. Despite the problems, Tabuk was selected to be the next location for the GR1 Tornados from both the UK and RAF Germany squadrons. On 24th September a 6 man UKMAMS team (including the flight commander, OC Mobile), deployed to Tabuk with the minimum required air cargo handling equipment to set up a reception airhead. In addition to the Tornado support equipment, large quantities of JP233 runway denial weapons were loaded outbound to be in place by 9th October. The original intent was to use the Hercules and VC-10 aircraft to load the weapons, but the sheer volume would have made the aircraft movements untenable.Instead the Airlift Coordination Cell were persuaded to use RAF TriStars with their greater carrying capacity. A TriStar is a big aircraft whose only entrances are at quite a distance above ground level - a specialised vehicle would be required to offload the aircraft, which was not available at Tabuk. The UKMAMS team were able to overcome this problem by "borrowing" one from the civil airport at Taif and transporting it back to Tabuk in a single Hercules sortie

Despite many problems caused by poor communications and vehicle unservicability, the deployment of the Tornados to Tabuk finished one day ahead of schedule. This was in no small part due to the cooperation of the USAF 5th Mobile Aerial Port Squadron who provided invaluable assistance throughout the operation.

The deployment of the 7th Armoured Brigade became one of the biggest tasks of the whole operation. The airstrip at Al Jubail was selected as the entry point as it was only 125 miles from the Kuwait border, had a runway that could handle wide-bodied aircraft and was close to a sea port.. The Royal Corps of Transport were given the task of handling the sea port while two teams from UKMAMS were responsible for establishing an airhead at the airfield.

Al Jubail was open for business on 28th September when it started to receive the brigades' airportable equipment, troops and support elements. The heavy equipment including tanks and personnel carriers were brought in by sea to the port.

The airhead became the focal point for many units en-route to the desert; 33 Field Hospital, support helicopter detachments and elements of the Tactical Supply Wing were just some that passed through Al Jubail. Inevitably the airfield was also destined to become a vital link in the re-supply of the ground forces.

The airhead became the focal point for many units en-route to the desert; 33 Field Hospital, support helicopter detachments and elements of the Tactical Supply Wing were just some that passed through Al Jubail. Inevitably the airfield was also destined to become a vital link in the re-supply of the ground forces.

The facilities were basic and the aircraft handling area was small. The whole of the British, American and Saudi forces shared just one international telephone. Once again, the MAMS team had insufficient ACHE for what was expected of them, but the American forces were able to provide help in this regard. An extra team was brought in and in just one month alone UKMAMS handled 11,000 passengers and 1,400,000 lbs of freight.

With the system running smoothly, albeit at full stretch, a change in policy was inevitable. ALCC in conjunction with HQ British Forces Middle East, initiated the hub & spoke concept of re-supply. The Gulf hub was located at King Khalid international airport in Riyadh and every other airhead was relegated to being a spoke. From now on freight was to be aggregated at Brize Norton and flown to Riyadh where it would be sorted into destination loads and then flown out to the spokes the following day on special in-theatre Hercules aircraft. To protect the delivery operation, up to 60 fighter aircraft were overhead on Combat Air Patrol at any given time.

The movements input to the hub was initially provided by 10 UKMAMS personnel. It soon became apparent that as the hub was handling all of the Gulf inbound freight, this number was barely half of what was realistically required. An additional 3 staff was provided.

In no time at all Riyadh was swamped with passengers and freight ultimately bound for the spokes. Mixed destination pallets from the UK that would require breaking down, sorting and rebuilding were a huge problem. Notwithstanding the Riyadh volume problems, it was a full month before the situation eased. For the other Gulf airheads the rush petered into a more manageable flow and manpower was pulled back where appropriate.

In no time at all Riyadh was swamped with passengers and freight ultimately bound for the spokes. Mixed destination pallets from the UK that would require breaking down, sorting and rebuilding were a huge problem. Notwithstanding the Riyadh volume problems, it was a full month before the situation eased. For the other Gulf airheads the rush petered into a more manageable flow and manpower was pulled back where appropriate.

During this period of hectic activity the order was received to move the Jaguar force from Thumrait to Bahrain. Once again Lyneham sent reinforcements to help with this move. The USAF offered manpower and airframes to help our overstretched forces and we requested 65 C-130 sorties of them. This they provided whilst the RAF carried out 16 sorties. Such was the level of help that the entire Jaguar force was settled into Bahrain within 5 days.

Meanwhile, back at Lyneham, the pressure was easing. Now that Brize Norton was involved in the operation, a lot of the routine re-supply freight went through their portals. This change in workload allocations provided a sudden glut of manpower and Lyneham was able to bring its' base shift system back up to 70% of their establishment. Now they were able to tackle the large backlog of cargo that had accumulated over the preceding months - at one point all of the car parks in Lyneham were full of freight.

By mid-November it was apparent that there would have to be a ground war to remove the Iraqis from Kuwait and the Western allies were going to have to start it. The Americans doubled their forces in-theatre and the British followed suit with the mobilization of our 4th Armoured Brigade who were to join the 7th and become the 1st Armoured Division. Once again the detachment at Al Jubail went into overdrive requiring, and receiving, a doubling of its manpower. Riyadh also increased their detachment size in anticipation of the increased workload.

On Christmas Eve the Royal New Zealand Air Force sent a handful of movers to Riyadh along with aircraft to support the in-theatre airlift which enabled the Riyadh movers to create a three shift system. The ability of Riyadh to handle TriStars was dramatically increased when a Soviet Antonov An-124 delivered a main base transfer loader from Germany and then delivered a second one to Al Jubail.

Iraq was given an ultimatum to remove themselves from Kuwait by 15th January. Load after load of tank tracks, spare engines and gear boxes were flown into theatre. A large variety of aircraft were gradually being employed by the MoD to take the pressure off of our own aircraft and crews. Various Boeing 707's with a myriad of nationalities started arriving. Heavy Lift were using their Belfast's and Guppies, Kuwait Airlines were operating their remaining Boeing 747 as a shuttle and numerous jobbing DC8's starting arriving from the USA. This increased the pressure on UKMAMS as they were now unloading a greater number and wider variety of aircraft than ever before.

The actual war was a short lived event, lasting only a matter of weeks. One month of intensive bombing followed by a week-long land campaign was sufficient to result in the "Mother of all Capitulations" as Saddam Hussein had predicted earlier on.

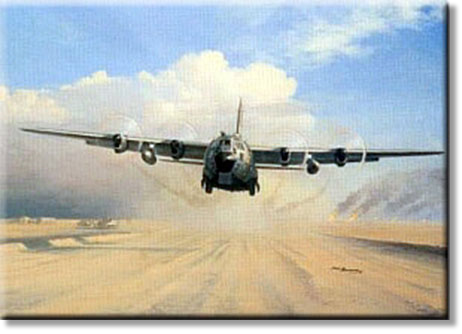

During the hostilities, the MAMS teams at all of the airheads were continuing to receive supplies and making preparations for the evacuation of large numbers of casualties. Supplies were also being delivered into rough desert airstrips and two MAMS teams were tasked forward to the battle area to form FOB's. Immediately before the start of operations against the Iraqis, the Air Commander in Riyadh announced that there would no longer be any roulement of personnel. This decision was very unpopular amongst those who just spent 6 months in the desert. With the ability to rotate and reinforce its teams removed, UKMAMS flexibility in-theatre was no longer there and the viewpoint was that a sustained operation would not be viable.

During the hostilities, the MAMS teams at all of the airheads were continuing to receive supplies and making preparations for the evacuation of large numbers of casualties. Supplies were also being delivered into rough desert airstrips and two MAMS teams were tasked forward to the battle area to form FOB's. Immediately before the start of operations against the Iraqis, the Air Commander in Riyadh announced that there would no longer be any roulement of personnel. This decision was very unpopular amongst those who just spent 6 months in the desert. With the ability to rotate and reinforce its teams removed, UKMAMS flexibility in-theatre was no longer there and the viewpoint was that a sustained operation would not be viable.

The Iraqis launched Scud missiles at regular intervals. Continual air raid warnings interspersed by the occasional explosion kept all of the Saudi detachment personnel on their toes. The FOB's were the closest of the MAMS detachments to the fighting. Their task was to support the re-supply of the forward elements of the 1st Armoured Division, provide a casualty evacuation facility and set up air evacuation for enemy POW's. The first FOB was set up just outside the town of Al Quysumah which was extremely close to the Iraqi front lines and amongst the forward lines of the US 101st Airborne Ranger Division. The FOB was used regularly by the support helicopter force and at the end of February it was used to transport Iraqi POW's on two specially provided DC9 aircraft.

Shorty after their arrival at the first FOB, four MAMS personnel were tasked to open a second one at a desert pumping station near Talon. Once again the FOB was intended to be used to fly support to the forward units, but in the event the Army decided to road move their logistic requirements and the FOB was largely unused.

A third FOB was set up quite close to the first to support 32 Field Hospital who were preparing for an anticipated influx of allied casualties and would require re-supply and evacuation facilities. In the event the hospital was thankfully not to be busy.

As the ground advance pushed into Kuwait, two further FOB's were established in their wake. Initially being used to bring forward supplies, they subsequently became airheads for the evacuation of the British soldiers after the conflict.

When the operation was starting to wind up, the auxiliary movers from Brize Norton were mobilized. These much-needed reinforcements were employed on both mobile and base duties and certainly proved their worth. The mobilization of the auxiliaries was a good decision, albeit a little late after their regular counterparts had been through some of their most difficult times. The auxiliaries were not to be under employed as the work of UKMAMS was set to increase still further when the recovery of the British assets in the Gulf was soon to begin.

When the operation was starting to wind up, the auxiliary movers from Brize Norton were mobilized. These much-needed reinforcements were employed on both mobile and base duties and certainly proved their worth. The mobilization of the auxiliaries was a good decision, albeit a little late after their regular counterparts had been through some of their most difficult times. The auxiliaries were not to be under employed as the work of UKMAMS was set to increase still further when the recovery of the British assets in the Gulf was soon to begin.

Although there was considerable sentiment that the allied forces remain in-theatre as a stabilizing influence, growing political pressure back home dictated the early repatriation of our forces. The priorities were to move the RAF squadrons and their equipment first followed by the Army and their equipment. The FOB's were used as troop assembly points where they were then shuttled to either Al Jubail or Kuwait International Airport for their trip home

Throughout the recovery, thousands of soldiers transited back to the UK through RAF Lyneham. There was no fanfare or welcoming committee, instead, after going through HM Customs arrivals procedures, they were unceremoniously herded onto waiting coaches.

The recovery was a busy, if uneventful, time for the MAMS teams who departed from Dhahran on the last TriStar out in mid-April. Elements of UKMAMS remained in Al Jubail to support the dwindling Army operations and help with the continued recovery of equipment and personnel still filtering back.

Without a doubt the personnel of UKMAMS, regardless of working from base or deployed areas, made an enormous contribution to the success of Operation Granby. At all times they acquitted themselves with professionalism and selflessness. In the face of little equipment or sympathetic understanding of their role or problems, they all demonstrated great ingenuity and flexibility. The squadron is justifiably proud of its motto and traditions which were so comprehensively upheld.

RAF TriStars at Riyadh. The pink one is being used for

air-to-air refuelling while the other is in the cargo role.

air-to-air refuelling while the other is in the cargo role.

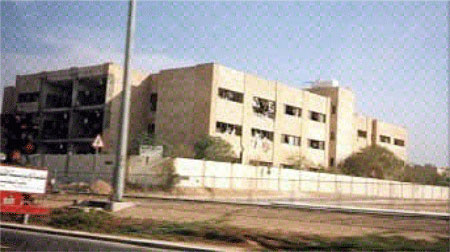

Riyadh - a damaged nursery after a SCUD attack

Ali Al Salem from the air

The pan at KKIA showing an RAF Hercules, RNZAF

Hercules, 5 VC-10 Tankers and 2 French Transalls

Hercules, 5 VC-10 Tankers and 2 French Transalls

Approaching the burning oil fields in Kuwait

Kuwait - The burning oil fields at 12 noon

A bombed-out hangar at Kuwait City Airport

Unloading the FUCHS force at Ali Al Salem. The two people under the tail are Flt Sgt Dave Roberts and Cpl John Belcher. The FUCHS force personnel are in the foreground.

The destroyed BA B747 which was caught on the

ground during the initial invasion in August 1990.

ground during the initial invasion in August 1990.

Kuwait International Airport - March 1991

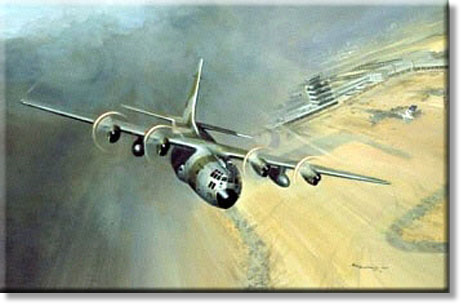

RAF C130 taking off from LZ3 in Iraq. Up to six landing zones (LZ's) were used during Operation Granby to resupply the spearhead of armour and Special Forces. They were also used to extract POWs

Abandoned Iraqi T62's at Kuwait Airport. These

three tanks are within the airport perimeter

three tanks are within the airport perimeter

This is one of the charter aircraft (Swiss,

of course) used to repatriate Iraqi POWs.

of course) used to repatriate Iraqi POWs.

Iraqi POW's being repatriated to their home.

No complaints from these passengers!

No complaints from these passengers!

Oil well fire - Kuwait March 1991. This was

the result of Saddam's "Scorched Earth" policy.

the result of Saddam's "Scorched Earth" policy.

This was the result of laser guided bombs (LGB). These are hardened aircraft shelters (HAS's) at Ali Al Salam Air Base in Kuwait where we now operate Tornado GR1 aircraft from as part of Operation Resinate South (enforcing of the 'no-fly' zone).

The Basra road became a bottleneck for retreating Iraqi forces - this is the result of sustained Alliance air attacks.

Kuwait International Air Terminal showing the remains of the terminal after the Iraqi withdrawal - time to get the brushes out!

Another shot of the destroyed BA747, this time looking from the terminal. When the Iraqis invaded Kuwait in August 1990 this aircraft was caught and destroyed on the ground. All of the passengers and crew were taken to Iraq and were used as 'human shields' until released on the intervention of ex-PM Edward Heath.

Iraqi ZSU3 Anti-Aircraft Gun which is now a UKMAMS trophy. This shows the AAA piece still in full working order with Herc Aircrew attached which was 'made safe' and recovered to UK. It now stands in front of UKMAMS HQ at Brize Norton.

The ATC Tower at Kuwait International

Looking along a main road in Kuwait city. (This picture was taken from a C130)

My wife and I were married on the 21st July 1990. We spent our honeymoon touring in Egypt. We were in Cairo on the 3rd August when we saw a Ferrari driving around with the occupants hanging out of the car waving the Kuwaiti flag. Eventually when we saw an English newspaper, we found out that Iraq had invaded Kuwait.

I was a corporal movements controller in the RAF, based at Lyneham in Wiltshire. My squadron, the United Kingdom Mobile Air Movements Squadron, was, and still is, responsible for the loading and unloading of all items that go onto the C-130 Hercules aircraft at Lyneham. Also the squadron has a mobile flight which flies with the aircraft to unload / load it if there isn't an RAF movements unit there.

I was a corporal movements controller in the RAF, based at Lyneham in Wiltshire. My squadron, the United Kingdom Mobile Air Movements Squadron, was, and still is, responsible for the loading and unloading of all items that go onto the C-130 Hercules aircraft at Lyneham. Also the squadron has a mobile flight which flies with the aircraft to unload / load it if there isn't an RAF movements unit there.

When I found out about the invasion, and knowing that Britain's response would be to deploy troops or aircraft to the Gulf, I knew that Lyneham would be heavily involved. Once again UKMAMS would be living up to it’s unofficial motto of “First in - Last Out”. Despite what any other unit might say, it was a Hercules carrying a UKMAMS team that deployed to the Gulf first!

My actual involvement with the Gulf started on 10 Aug. when I went into work to the “organised” chaos that had taken over. Normally the shift pattern was 2 days, 2 nights, and 4 off (12 hour duties). Well this had gone out of the window after a day and we were now working 2 days, 2 nights, and 2 off. This later changed to 3-3-3. I was initially working in the passenger section looking after passengers and their bags. Later on I ended up working in Load Control, collating the aircraft paperwork and producing trim (load) sheets.

My actual involvement with the Gulf started on 10 Aug. when I went into work to the “organised” chaos that had taken over. Normally the shift pattern was 2 days, 2 nights, and 4 off (12 hour duties). Well this had gone out of the window after a day and we were now working 2 days, 2 nights, and 2 off. This later changed to 3-3-3. I was initially working in the passenger section looking after passengers and their bags. Later on I ended up working in Load Control, collating the aircraft paperwork and producing trim (load) sheets.

During the Christmas holidays of 1990, I managed to get 2 days leave (Christmas and Boxing days). BIG MISTAKE. While I was away, the Mobile flight needed reinforcements and each shift had to provide 3 people. As I wasn't there, I was ‘volunteered’ for a month in Riyadh. As the UN deadline ran out 10 days after we were due to arrive, we were told that the month might last a bit longer.

The 3rd January, when the rest of the station came back from their leave, saw the lucky volunteers touring round the station getting all their kit. Clothing stores to draw 6 NBC suits and 3 canisters for the respirator (don’t not take them out of the protective covering until told to - they are in short supply); Medical centre (how many jabs can you fit in one arm?); RAF Regiment to get a refresher course on our our weapon, the 9 mm pistol, and refresher training on how to survive a chemical or biological attack; Admin. (Have you made a will?).

The 3rd January, when the rest of the station came back from their leave, saw the lucky volunteers touring round the station getting all their kit. Clothing stores to draw 6 NBC suits and 3 canisters for the respirator (don’t not take them out of the protective covering until told to - they are in short supply); Medical centre (how many jabs can you fit in one arm?); RAF Regiment to get a refresher course on our our weapon, the 9 mm pistol, and refresher training on how to survive a chemical or biological attack; Admin. (Have you made a will?).

The Regiment told us that as there had been an error with the ammunition supply, we could either use our 26 rounds (2 magazines) on the range to practice with or take them to the Gulf! Apparently the Army was now responsible for ordering all ammunition for the 3 Services and as they no longer used 9 mm they didn't think anyone else did. So none was ordered!

5th January we report to Lyneham for transport to Brize Norton and our shiny TriStar flight. The inside of the TriStar had been converted so that it could carry freight and passengers together. The aircraft could carry up to 20 pallets and ours was carrying 16 freight pallets, 4 of seats. It took 6 hours to get to Riyadh and we arrived in the middle of the night. The TriStar was offloaded, back loaded with freight and passengers bound for Germany or the UK, and then departed.

5th January we report to Lyneham for transport to Brize Norton and our shiny TriStar flight. The inside of the TriStar had been converted so that it could carry freight and passengers together. The aircraft could carry up to 20 pallets and ours was carrying 16 freight pallets, 4 of seats. It took 6 hours to get to Riyadh and we arrived in the middle of the night. The TriStar was offloaded, back loaded with freight and passengers bound for Germany or the UK, and then departed.

Riyadh had been set up as the “hub at the centre of a supply wheel”. The TriStar brought the freight from the UK. It was then transferred to a mini fleet of Hercules who would then ferry it to the various Gulf bases at Dhahran, Tabuk, Dubai, Al Jubail, Seeb, Al Quaisumah and any of the small desert landing strips. These were in addition to the direct re-supply flight to those locations. The freight they brought back was then loaded to the following night's TriStar that would return to the UK via Germany. As the RAF Hercules were in short supply (what a surprise), we had 2 New Zealand Hercules working with the RAF Detachment. The Kiwi movers worked with us as an integrated part of the MAMS detachment.

The RAF detachment were working from King Khalid International Airport (KKIA). We were based in a new terminal building, which was partially completed. At first it was just the Hercules (RAF and Kiwi), 101 Sqn VC10 tankers and 216 Sqn TriStar tankers. When war looked more likely, we were joined by 205 General Hospital and all their attendant units. The airport was still being used for some civilian flights. The other military user of the airfield was France with some Transalls. They were totally separate from us.

The RAF detachment were working from King Khalid International Airport (KKIA). We were based in a new terminal building, which was partially completed. At first it was just the Hercules (RAF and Kiwi), 101 Sqn VC10 tankers and 216 Sqn TriStar tankers. When war looked more likely, we were joined by 205 General Hospital and all their attendant units. The airport was still being used for some civilian flights. The other military user of the airfield was France with some Transalls. They were totally separate from us.

The working pattern was the same as at Lyneham 2, 2 and 2. All went well for the next few days until the UN deadline passed without Iraq withdrawing from Kuwait. Our normal nightly TriStar had arrived and was being turned around as usual. Then the air raid warning was given. The air war had started in the early hours of 15th Jan 1991. There was mad frenzy of trying to contact the teams on the aircraft pan, putting on NBC suits and respirators (yes they had been unwrapped despite what the suppliers had told us). We trooped down to the concourse on the ground floor of the airport and sat around waiting. Someone pointed out that the people who had decided that this area was the shelter had not chosen too wisely. The front of the terminal was plate glass! Anyway nothing happened, the all-clear was given and we set back to loading the aircraft. Apparently the first wave of bombers had just struck and the warning had been given just in case of any retaliatory strikes that might happen. The air raid was sounded about 3 times that night. As I remember when the war ended I saw a report saying that the air raid had gone off 63 times.

It was quickly announced that there was would be no aircraft movements other than the fast jets. The TriStar and all Hercules flights were suspended for 3 days. We were sent back to our accommodation compound to watch the war unfolding on Saudi TV. Not that we found out much as the TV was heavily censored. Finally it was realised that if the air war was to carry on then resupply flights would have to resume. The fast jets couldn’t fight without some help from the rest of the air force. We now started the normal resupply procedures, only there was a greater sense of urgency now. We still had about 2 air raid warnings a night. The satellites would pick up the signs of a Scud missile launch and put out a general warning until it became apparent where the target was.

We handled a number of foreign aircraft that were used to evacuate their country's embassy staff. A Portuguese Herc was held up because the Saudis wouldn’t let the staff go until they had cleared immigration. The Portuguese Ambassador pointed out that “there was a war on” and they were going whatever because of the threat of a missile attack. With that a Scud alert was sounded. We guided the civilians to the shelter where we sat and waited in our NBC suits and respirator. Some of the Portuguese had respirators but the majority including many children didn't. It was decided that if the missile was carrying a chemical agent then the children would be put in casualty bags until the threat had passed. That was all that could be done, as we had no spare respirators. Luckily this and all the other missiles were carrying normal explosives.

We handled a number of foreign aircraft that were used to evacuate their country's embassy staff. A Portuguese Herc was held up because the Saudis wouldn’t let the staff go until they had cleared immigration. The Portuguese Ambassador pointed out that “there was a war on” and they were going whatever because of the threat of a missile attack. With that a Scud alert was sounded. We guided the civilians to the shelter where we sat and waited in our NBC suits and respirator. Some of the Portuguese had respirators but the majority including many children didn't. It was decided that if the missile was carrying a chemical agent then the children would be put in casualty bags until the threat had passed. That was all that could be done, as we had no spare respirators. Luckily this and all the other missiles were carrying normal explosives.

In the event only 1 Scud came down anywhere near the RAF detachment in Riyadh. It landed during the night near a nursery/children's school about 1 mile away from the compound we had moved to. The building was quite badly damaged. I managed to sleep right through the whole alert and woke to find that the compound had spent the night in the underground car park.

When the war ended, the race started to be the first Hercules to land at Kuwait City. KKIA launched a flight carrying staff and some stuff for the British embassy. Diplomats first! But the Hercules being used by the Special Forces, which had declared an emergency as it was supposedly running short of fuel and landed at Kuwait to refuel, beat them. The flight from KKIA carried 4 MAMS people to set up the Movements Detachment Kuwait.

When the war ended, the race started to be the first Hercules to land at Kuwait City. KKIA launched a flight carrying staff and some stuff for the British embassy. Diplomats first! But the Hercules being used by the Special Forces, which had declared an emergency as it was supposedly running short of fuel and landed at Kuwait to refuel, beat them. The flight from KKIA carried 4 MAMS people to set up the Movements Detachment Kuwait.

I managed to get a seat on one of the resupply flights to Kuwait via Al Jubail. Unfortunately it broke down at Al Jubail and that looked like the end of my trip until a Kiwi Hercules landed and said they were going to Kuwait and I could jump on with them. Although it was mid afternoon, most of the flight was spent in darkness flying through the burning oil fields of Kuwait. The Iraqis had set fire to the oil wells as they retreated. I had about 10 minutes to look around at Kuwait airport. Just long enough to see the remains of the British Airways Jumbo jet the had landed at Kuwait just the invasion was happening. It was bombed by the Americans in the air war.

The only other place that I saw in Kuwait was the Ali Al Salem (AAS) air base. We were detailed to recover the RAF Regiment and Army NBC recce team (FUCH’s Force, after the type of vehicle they used). AAS had been bombed by the Allies, each of the HAS (Hardened Aircraft Shelters) had a hole in the roof. These were meant to be bomb proof! We made 2 lifts into AAS and it was planned to recover the rest of the team the next day.

The only other place that I saw in Kuwait was the Ali Al Salem (AAS) air base. We were detailed to recover the RAF Regiment and Army NBC recce team (FUCH’s Force, after the type of vehicle they used). AAS had been bombed by the Allies, each of the HAS (Hardened Aircraft Shelters) had a hole in the roof. These were meant to be bomb proof! We made 2 lifts into AAS and it was planned to recover the rest of the team the next day.

When we got back to KKIA my boss asked if I was ready to go home? Was I! A month detachment had lasted for almost 3 months. I flew home on the 25th March 1991 on a Hercules non-stop to Lyneham. There were 2 other passengers, another Mover and a Signaller. He was escorting a Landrover. The only other freight was a captured Iraqi Anti Aircraft gun. This trophy is now on display next to an Argentine mortar from the Falklands outside the UKMAMS HQ building at RAF Lyneham. We landed at Lyneham to a rapturous welcome. . . from HM Customs and Excise! The welcoming parties had stopped weeks before.

The war was a surreal experience in some respects. At one stage we were living in a top hotel with visiting businessmen yet we were walking around carrying pistols, NBC suits and respirators. (we had to buy small civilian rucksacks to hide the suits and weapons in). Driving back to the hotel one night we saw what looked like a fireworks display in the distance. We realised that it was Patriot missile that had been launched at an incoming Scud. Yet everyone carried on driving as if nothing was happening. God only knows what would have been the outcome if it had been carrying a chemical agent.

One good thing did come from the war - my son was born 9 months and 3 days after I returned!

Note - Ali Al Salem is now used as the base for RAF Tornadoes flying in support of the UN embargo on flights by the Iraqis

One good thing did come from the war - my son was born 9 months and 3 days after I returned!

Note - Ali Al Salem is now used as the base for RAF Tornadoes flying in support of the UN embargo on flights by the Iraqis